Private Purpose Trusts

Private purpose trusts

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

■ understand the rationale behind the general rule of non-enforceability of private purpose trusts

■ comprehend the rule against perpetuities

■ recognise the exceptions to the Astor principle

■ define the Denley principle

■ define an unincorporated association and appreciate the difficulties created in respect of gifts to such associations

11.1 Introduction

Attorney General

The legal adviser to the government, in addition the legal representative of objects under a charitable trust.

An additional requirement concerning express private trusts is the need to identify beneficiaries who are capable of enforcing the trust. A purpose, as expressed by the settlor, is incapable of enforcing a trust. Alternatively, a public purpose trust, or charitable trust, is capable of being enforced by the Attorney General. One of the duties of the Attorney General is to act as a representative of the Crown on behalf of charitable bodies. In this context a charitable trust is a trust that promotes a public benefit and advances one or more of the 13 purposes laid down in the Charities Act 2006. Many of these purposes coincide with the law on charitable purposes that preceded the 2006 Act.

An intended private purpose trust is void. A purpose trust is designed to promote a purpose as an end in itself, for instance the discovery of an alphabet of 40 letters, to provide a cup for a yacht race, or the boarding up of certain rooms in a house. Such intended trusts are void, for the court would be incapable of supervising their proper administration. As there is no beneficiary with a locus standi capable of enforcing such a trust, there is a real risk that improper behaviour by the trustees could go unnoticed. In consequence, a resulting trust arises in favour of the donor or settlor, on the failure of a non-charitable purpose trust.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Morice v Bishop of Durham [1804] 9 Ves 399 |

| A bequest was made to the Bishop of Durham on trust for ‘such objects of benevolence and liberality as the Bishop of Durham shall in his own discretion most approve of’. The court decided that this bequest failed as a charity because the objects were not exclusively charitable, and was invalid as a private trust, for there were no ascertainable beneficiaries. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘[I]t is a maxim, that the execution of a trust shall be under the control of the court, it must be of such a nature, that it can be under that control; so that the administration of it can be reviewed by the court; or, if the trustee dies, the court itself can execute the trust; a trust therefore, which, in case of maladministration could be reformed; and a due administration directed; and then, unless the subject and objects can be ascertained, upon principles, familiar in other cases, it must be decided, that the court can neither reform maladministration, nor direct a due administration.’ |

| Lord Eldon |

The court came to a similar conclusion in Re Astor’s Settlement Trust [1952] Ch 534.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Astor’s Settlement Trust [1952] Ch 534 |

| Lord Astor purported to create a trust for ‘the maintenance of good understanding between nations and the preservation of the independence and integrity of newspapers’. The court held that the trust was void for uncertainty on the grounds that the means by which the trustees were to attain the stated aims were unspecified and the person who was entitled, as of right, to enforce the trust was unnamed. In other words, a trust creates rights in favour of beneficiaries and imposes correlative duties on the trustees. If there are no persons with the power to enforce such rights, then equally there can be no duties imposed on trustees. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘[T]he only beneficiaries are purposes and at present unascertainable persons, it is difficult to see who could initiate proceedings. If the purposes are valid trusts, the settlors have retained no beneficial interest and could not initiate them. It was suggested that the trustees might proceed ex parte to enforce the trusts against themselves. I doubt that, but at any rate nobody could enforce the trusts against them.’ |

| Roxburgh J |

ex parte

An interested person who is not a party; or, by one party in the absence of the other.

11.2 Reasons for failure of a private purpose trust

There are a number of common reasons why private purpose trusts fail. The list is not exhaustive, but pitfalls which a settlor should avoid are:

■ the lack of a beneficiary principle;

■ uncertainty of objects; and

■ the infringement of the perpetuity rule.

11.2.1 Lack of beneficiaries

A trust is mandatory in nature and imposes enforceable obligations on the trustees. Those capable of enforcing such obligations are the beneficiaries. These persons are granted rights in rem in the subject-matter of the trust. The courts have always jealously guarded the rights and interests of the beneficiaries under trusts. But such rights may be protected only if the beneficiary has a locus standi to enforce the same. Purposes cannot initiate proceedings against the trustees. Accordingly, a purported trust for private purposes is void because it lacks a beneficiary. In effect, in trusts law the courts regard two features of primary importance, namely ownership of property and the fiduciary office of trusteeship. The beneficiary, as an equitable owner, has the capacity of ensuring that the trustees carry out their duties in a responsible manner.

In other jurisdictions, such as the Cayman Islands, an alternative philosophy has been adopted whereby a settlor may expressly nominate a person to be obliged to enforce a private purpose trust against the trustees. In this context the focus of attention is not ownership but enforcement. The ‘enforcer’ has a public duty to enforce the trust, which is followed up with severe penalties for breaches. On analogy, the English equivalent of such a third person is the Attorney General, but only in respect of charities.

11.2.2 Uncertainty

As a corollary to the above-mentioned rule, it is obvious that the rights of the beneficiaries will be illusory unless the court is capable of ascertaining to whom those rights belong. Thus, as a second ground for the decision in Re Astor (1952), the trust failed for uncertainty:

JUDGMENT

| ‘If an enumeration of purposes outside the realm of charities can take the place of an enumeration of beneficiaries, the purposes must be stated in phrases which embody definite concepts and the means by which the trustees are to try to attain them must also be prescribed with a sufficient degree of certainty.’ |

| Roxburgh J |

A case which illustrates this principle is Re Endacott [1960] Ch 232.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Endacott [1960] Ch 232 |

| A testator transferred his residuary estate to the Devon Parish Council ‘for the purpose of providing some useful memorial to myself. Lord Evershed MR held that no out-and-out gift to the Council was created, but the testator intended to impose an obligation in the nature of a trust on the Council, which failed for uncertainty of objects. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘[N]o principle has greater sanctity of authority behind it than the general proposition that a trust by English law, not being a charitable trust, in order to be effective must have ascertained or ascertainable beneficiaries.’ |

| Lord Evershed MR |

11.2.3 Perpetuity rule

The perpetuity rule is a common law principle (as modified by statute) of general application in property law which restricts the maximum period in which the vesting of property, real or personal, may be postponed (the rule against remote vesting). In addition, if the property has vested in the beneficiary the rule specifies the maximum period in which the property is required to be retained (the rule against excessive duration).

The Law Commission in its 1998 report on the ‘Rules against perpetuities and accumulations’ concluded that the principle is unnecessarily complex, out of date and disproportionate in its extension to commercial transactions. The report recommended a fundamental reform of measuring the perpetuity period.

QUOTATION

| The application of the rule against perpetuities has developed over time and is now too wide. It applies to many commercial dealings (such as future easements, options and rights of preemption) which have nothing to do with the family settlements that the rule was designed to control. The application of the rule to pension schemes is not consistent with the policy of the rule. | ||

| The existence of multiple methods for calculating the perpetuity period (which includes the use of lives in being at common law, as well as periods of up to 80 years under the 1964 Act) is unnecessarily complex and confusing. In addition, the use of lives in being gives rise to practical difficulties. For example, where a “royal lives clause” has been used, it may be impossible for the trustees to identify who the last remaining descendants of a monarch are, or indeed whether they are still alive.’ | ||

The Law Commission recommendations were endorsed in the Perpetuities and Accumulations Act 2009 (which came in to force on 6 April 2010). Section 5 of the Act abolishes the general common law period and substitutes a precise, standard period that does not exceed 125 years. This period is applicable to both aspects of the perpetuity rule, namely the rule against remote vesting and the rule against excessive duration. The 125-year period is an overriding provision that is written into all instruments taking effect on or after 6 April 2010. The effect is that a gift is required to vest in the donee within 125 years from the date of the execution of the instrument creating the gift, and provided that the gift has vested, may not be inalienable for a period exceeding 125 years. The Act is not retrospective, and does not affect gifts in instruments taking effect before the date when the Act came into force. However, s 18 of the 2009 Act excludes non-charitable purpose from the 125-year perpetuity period. The effect is that the common law periods of ‘a life or lives in being and/or 21 years’ continue to apply to private purpose trusts. This is outlined below.

At common law, the perpetuity period was measured in terms of a life or lives in being, plus 21 years. Time begins to run from the date that the instrument creating the gift takes effect (a will takes effect on the date of the death of the testator or testatrix; a deed takes effect on the date of execution). Only human lives may be chosen and not the lives of animals, some of which are noted for their longevity (such as tortoises and elephants). An embryonic child (en ventre sa mère) constitutes a life in being if this is relevant in measuring the period. A life or lives in being, whether connected with the gift or not, may be chosen expressly by the donor or settlor in order to extend the perpetuity period. Any number of lives may be selected. The test is whether the group of lives selected is certain and identifiable to such an extent that it is practicable to ascertain the date of death of the last survivor. This test was clearly incapable of being satisfied in Re Moore [1901] 1 Ch 936, where a testator defined the period as ‘21 years from the death of the last survivor of all persons who shall be living at my death’. The gift was considered void for uncertainty.

Indeed, the settlor may even select lives which have no connection with the trust. It became the practice to select royal lives, such as ‘the lineal descendants of Queen Elizabeth II living at my death’, with the objective of ascertaining the date of death of the last survivor.

Alternatively, a life or lives in being may be implied in the circumstances if the life or lives is or are so related to the gift or settlement that it is or they are capable of being used to measure the date of the vesting of the interest. If no lives are selected or are implied, the perpetuity period at common law is 21 years from the date of the creation of the gift.

ab initio

From the beginning.

The common law approach to the perpetuity rule was based on the assumption that if there was a mere possibility, however slight, that a future interest may vest outside the perpetuity period, the grant of the interest is void ab initio. This was the approach of the courts before 1964. For example, if S, a settlor, during his lifetime transfers a portfolio of shares to T1 and T2 as trustees, on trust contingently for his first child to marry and S has unmarried children, this gift, before the Perpetuities and Accumulations Act 1964, would be void. S would be treated impliedly as the life in being and it was possible that none of his children would marry within 21 years after his death. Thus, there was a possibility that the gift might not vest within the perpetuity period.

The Perpetuities and Accumulations Act 1964 introduced three major reforms to the law. Under the Act, a future interest is no longer void on the ground that it ‘might’ vest outside the perpetuity period. It is void if, in the circumstances, the interest does not vest within the perpetuity period. In the meantime, the court will ‘wait and see’ whether or not the gift vests. Moreover, the Act introduced a certain and fixed period not exceeding 80 years which the grantor may expressly nominate as the perpetuity period. In addition, s 3(5) of the Act introduced a variety of persons who may be treated as a ‘statutory life’. These are: the grantor, the beneficiary or potential beneficiary, the donee of a power, option or other right, parents and grandparents of the grantor and any person entitled in default. Where there are no lives within any of these categories, the ‘wait and see’ period is 21 years from the date the instrument takes effect.

Closely related to the perpetuity rule is the rule against excessive duration. This rule renders void any obligation to retain property for longer than the perpetuity period. The issue here is not whether the property or interest is, in fact, tied up forever but whether the owner is capable of disposing of the same within the perpetuity period. The question concerns merely the power to dispose of the capital. Thus, property may be owned perpetually by persons, companies or unincorporated associations if these bodies are entitled to dispose of the same at any time.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Chardon [1928] Ch 464 |

| A testator gave a fund to a cemetery company subject to the income being required to be used for the maintenance of two specified graves, with a gift over. The court held that the gift was valid, for the company was capable of alienating the property. |

Charitable trusts, because of their public nature, are exempt from this principle.

11.3 Exceptions to the Astor principle

There are a number of private purpose trusts which are exceptionally considered to be valid. Despite the objections to the validity of purpose trusts as stated above, a number of anomalous exceptions exist. These trusts are created as concessions to human weakness. But it must be emphasised that the only concession granted by the courts is that it is unnecessary for the beneficiaries (purposes) to enforce the trust. The other rules applicable to express trusts are equally applied to these anomalous trusts (see Re Endacott (1960), above). Accordingly, such gifts are required to satisfy the test for certainty of objects and the perpetuity rule. These exceptionally valid trusts are not mandatory in effect but are merely ‘directory’ in the sense that the trustees are entitled to refuse to carry out the wishes of the settlor and the courts will not force them to do otherwise. At the same time, the courts will not forbid the trustees from carrying out the terms of the trust, if they express an intention to do so. In the latter event the traditional fiduciary duties attach to the trustees. These anomalous trusts are called ‘hybrid trusts’ or ‘trusts for imperfect obligations’.

11.3.1 Trusts for the maintenance of animals

Gifts for the maintenance of animals generally are charitable, but trusts for the maintenance of specific animals, such as pets, are treated as valid private purpose trusts.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Petting all v Pettingall [1842] 11 LJ Ch 176 |

| The testator’s executor was given a fund in order to spend £50 per annum for the benefit of the testator’s black mare. On her death, any surplus funds were to be taken by the executor. The court held that in view of the willingness of the executor to carry out the testator’s wishes, a valid trust in favour of the animal was created. The residuary legatees were entitled to supervise the performance of the trust but they were not the primary beneficiaries. They were interested not in the validity of the gift but in its failure. |

In Re Dean (1889) 41 Ch D 552, the testator directed his trustees to use 750 per annum for the maintenance of his horses and hounds should they live so long. It was held that the trust was valid. The difficulty with this case is the possible infringement of the perpetuity rule. The court treated the horses and hounds as the lives in being for the purpose of the perpetuity rule. It was stated earlier that for the purpose of the perpetuity rule a ‘life’ is treated as a human life. In any event, it was unclear who was entitled to enforce the trust against the trustees. In Re Kelly [1932] IR 255, the court took the view that lives in being were required to be human lives. In any event the court is entitled to take judicial notice of the lifetime of animals. In Re Haines, The Times, 7 November 1952, the court took notice that a cat could not live for longer than 21 years.

In Re Thompson [1934] Ch 342, the Pettingall principle was unjustifiably extended to uphold a trust for the promotion and furtherance of fox hunting.

11.3.2 Monument cases

A trust for the building of a memorial or monument in memory of an individual is not charitable, but may exist as a valid purpose trust if the trustees express a desire to perform the task.

On the other hand, a gift for the maintenance of all the graves in a churchyard may be charitable.

11.3.3 Saying of masses

In Bourne v Keane [1919] AC 815, the House of Lords decided that the saying of masses was valid. Prior to this decision the courts had adopted the view that such trusts were void, not because of the lack of a human beneficiary, but because they were superstitious activities. It should be noted that the Bourne (1919) principle is now restricted to masses to be said in private, for public masses may be treated as charitable events (see later). In Khoo Cheng Teow [1932] Straits Settlement Reports 226, a trust for the performance of non-Christian ceremonies was upheld as a valid private purpose trust.

11.4 The Denley approach

The approach adopted by the courts is to ascertain whether a gift or trust is for the promotion of a purpose simpliciter (within the Astor principle) which is void, or alternatively whether the trust is for the benefit of persons who are capable of enforcing the trust. This is a question for the courts to decide, on construction of the relevant trust instrument. The promotion of virtually any purpose will affect persons. The settlor may, in form, create what appears to be a purpose trust but, in substance, the trust may be considered to be for the benefit of human beneficiaries.

In this respect, there is a distinction between a form of gift remotely in favour of individuals, to such an extent that those individuals do not have a locus standi to enforce the trust. On the other hand, a gift may appear to propagate a purpose which is directly or indirectly for the benefit of individuals. In this event, if the beneficiaries satisfy the test for certainty of objects, the gift may be valid. The courts are required to consider each gift prior to classification.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Bowes [1896] 1 Ch 507 |

| A testator bequeathed a fund for the planting of a clump of trees on land settled for the benefit of A and B. A and B did not want the money to be used for the planting of the trees but instead claimed the money for their benefit. North J held in favour of A and B on the ground that, on construction of the will, the money was intended for the benefit of the individuals and not for the benefit of the estate. The expressed purpose of planting trees was not intended to be imperative, but merely indicated the testator’s motive for creating a trust for the benefit of A and B. |

A similar approach was adopted in Re Denley’s Trust Deed [1969] 1 Ch 373:

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Denley’s Trust Deed [1969] 1 Ch 373 |

| A plot of land was conveyed to trustees for use, subject to the perpetuity rule, as a sports ground primarily for the benefit of employees of a company and secondarily for the benefit of such other person or persons as the trustees may allow to use the same. The question in issue was whether the trust was void as a purpose trust. Goff J held that the trust was valid in favour of human beneficiaries. The test for certainty of objects and the perpetuity rule were satisfied. The court stated that the objection to purpose trusts was not that they sought to achieve a purpose but that they lacked any human beneficiary to enforce them. Thus, the ‘lack of beneficiary principle’ applied only where the trust was abstract or impersonal as opposed to where the trust, though expressed as a purpose, was directly or indirectly for ascertainable beneficiaries, within the perpetuity rule and was not otherwise uncertain. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘I think there may be a purpose or object trust, the carrying out of which would benefit an individual or individuals, where that benefit is so indirect or intangible or which is otherwise so framed as not to give those persons any locus standi to apply to the court to enforce the trust, in which case the beneficiary principle would, as it seems to me, apply to invalidate the trust, quite apart from any question of uncertainty or perpetuity. Such cases can be considered if and when they arise. The present is not, in my judgment, of that character, and it will be seen that clause 2(d) of the trust deed expressly states that, subject to any rules and regulations made by the trustees, the employers of the company shall be entitled to the use and enjoyment of the land. |

| Where the trust, though expressed as a purpose, is directly or indirectly for the benefit of an individual or individuals, it seems to me that it is in general outside the mischief of the beneficiary principle … In my judgment, however, it would not be right to hold the trust void on this ground [lack of beneficiary]. The court can, as it seems to me, execute the trust both negatively by restraining any improper disposition or use of the land, and positively by ordering the trustees to allow the employees and such other persons (if any) as they may admit to use the land for the purpose of a recreation or sports ground.’ | |

| Goff J |

The issue in Denley concerned the classification of the nature of the trust. Was it a private purpose trust (void), or a traditional private trust for ascertainable human beneficiaries (valid)? The court decided that the trust was valid for an ascertainable group of beneficiaries. The focus of attention, in the court’s view, was the issue of enforceability, i.e. whether the trust was capable of being enforced by beneficiaries who satisfied the test for certainty of objects. The problem with this approach is that it is questionable whether the gift corresponded with a traditional private trust. In a traditional private trust the beneficiaries acquire ‘in rem’ interests in the property and may be capable of terminating the trust under the Saunders v Vautier principle. It is arguable that these features were absent in Denley, for the beneficiaries amounted to a fluctuating class of objects, namely the employees of the company and others permitted to benefit at the instance of the trustees. The Denley principle was applied by Oliver J in Re Lipinski (1977) (see later), a case involving a gift to an unincorporated association. Oliver J explained Denley as a private trust, although expressed as a purpose, but was directly or indirectly for the benefit of individuals who were ascertainable. In Re Grant’s Will Trust (1980) (see later), Vinelott J endorsed the approach in Denley but regarded the decision as a discretionary trust case.

KEY FACTS

| Private purpose trusts | |||

| Trusts to promote private purpose trusts | Void | Lack of a beneficiary with a locus standi to enforce | Morice v Bishop of Durham (1804); Leahy v A-G for NS Wales (1959) (see below); Re Astor (1952) | |

| Exceptions | ||||

| ■ Maintenance of animals | Valid | Subject to the tests of certainty and perpetuity | Pettingall v Pettingall (1842); Re Haines | |

| ■ Erection of monuments | Valid | Subject to the tests of certainty and perpetuity | Musset v Bingle (1876) | |

| ■ Maintenance of monuments | Valid | Subject to the tests of certainty and perpetuity | Re Hooper (1932) | |

| ■ Saying of masses (N.B. could be charitable) | Valid | Subject to the test of perpetuity | Bourne v Keane (1919) | |

| ■ Alternatively, on construction (subject to the tests of certainty and perpetuity) the court may decide that a gift for a purpose may be treated as a gift for persons | Valid | Enforcement by beneficiaries | Re Bowes (1896); Re Denley (1969) | |

ACTIVITY

| Applying the law John, who has recently died, by his will bequeathed the following legacies: (1) 5,000 to use the income each year to provide a trophy for the winner of the Utopia Yacht Racing Competition, an annual event organised by the Utopia Yacht Club. (2) £600 to my executors to maintain my pet cat, Tiddles, for the rest of her life. (3) £15,000 to erect and maintain a tombstone, for a period not exceeding 21 years, in memory of my late wife, Ophelia. (4) £500 to the vicar of my parish church in Utopia for the saying of private masses for my soul. Consider the validity of these bequests. |

11.5 Gifts to unincorporated associations

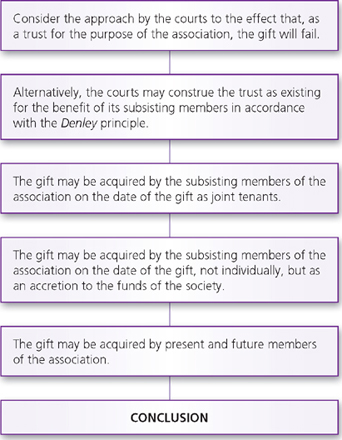

There is some difficulty in deciding whether a gift to an unincorporated association creates a trust for a purpose which fails for want of a beneficiary to enforce the trust (under the Astor (1952) principle), or whether the gift will be construed in favour of human beneficiaries, the members of the association. This involves a question of construction of the circumstances surrounding the gift and the rules of the association.

For instance, a gift to the National Anti-Vivisection Society (an unincorporated non-charitable body) may be construed as a gift on trust for the work or purpose of such association and not for the benefit of its members. Accordingly, the gift may be considered void under the Astor (1952) principle.

JUDGMENT

| ‘A gift can be made to persons (including a corporation) but it cannot be made to a purpose or to an object. So also, a trust may be created for the benefit of persons as cestuis que trust but not for a purpose or object unless the purpose or object be charitable. For a purpose or object cannot sue, but if it be charitable, the Attorney-General can sue to enforce it.’ |

| Viscount Simonds in Leahy v A-G for New South Wales [1959] AC 457 |

An unincorporated association (as distinct from an incorporated association) is not a legal person but may take the form of a group of individuals joined together with common aims, usually laid down in its constitution. The association was defined by Lawton LJ in Conservative and Unionist Central Office v Burrell [1982] 1 WLR 522. In this case the Court of Appeal decided that the Conservative Party was not an unincorporated association but an amorphous combination of various elements. The legal rights created in favour of donors and contributors exist on the basis of a mandate or agency.

JUDGMENT

| ‘[An unincorporated association means] … two or more persons bound together for one or more common purposes, not being business purposes, by mutual undertakings each having mutual duties and obligations, in an organisation which has rules which identify in whom control of it and its funds rests and on what terms and which can be joined or left at will.’ |

| Lawton LJ |

In Neville Estates Ltd v Madden [1962] Ch 832, Cross J, in an obiter pronouncement, outlined various constructions concerning gifts or trusts in favour of unincorporated associations:

JUDGMENT

| ‘The position, as I understand it, is as follows. Such a gift may take effect in one or other of three quite different ways. In the first place, it may, on its true construction, be a gift to the members of the association at the relevant date as joint tenants, so that any member can sever his share and claim it whether or not he continues to be a member of the association. Secondly, it may be a gift to the existing members not as joint tenants, but subject to their respective contractual rights and liabilities towards one another as members of the association. In such a case a member cannot sever his share. It would accrue to the other members on his death or resignation, even though such members include persons who become members after the gift took effect. If this is the effect of the gift, it will not be open to objection on the score of perpetuity or uncertainty unless there is something in its terms or circumstances or in the rules of the association which precludes the members at any given time from dividing the subject of the gift between them on the footing that they are solely entitled to it in equity. Thirdly, the terms or circumstances of the gift or the rules of the association may show that the property in question is not to be at the disposal of the members for the time being, but is to be held in trust for or applied for the purposes of the association as a quasi-corporate entity. In this case the gift will fail unless the association is a charitable body. If the gift is of the second class, i.e. one which the members of the association for the time being are entitled to divide among themselves, then, even if the objects of the association are in themselves charitable, the gift would not, I think, be a charitable gift.’ |

Gift to members as joint tenants

A settlor may make a gift to an unincorporated association which, on a true construction, is a gift to the members of that association who take as joint tenants free from any contractual fetter. Any member is entitled to sever his share and may claim it beneficially. In these circumstances, the association is used as a label or definition of the class which is intended to take. For instance, a testator might give a legacy to a dining or social club of which he is a member with the intention of giving a joint interest, which is capable of being severed, to the members. Such cases are extremely uncommon.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Cocks v Manners [1871] LR 12 Eq 574 |

| The testatrix left part of her estate to the Dominican Convent at Carisbrooke, ‘payable to the supervisor for the time being’. The court held that the gift was not charitable but was valid in favour of the individual members of the stated community as joint tenants. |

Gift to members (subsisting) as an accretion to the funds

More frequently, the gift to the association may be construed as a gift to the members of the association on the date of the gift, not beneficially, but as an accretion to the funds of the society which is regulated by the contract (evidenced by the rules of the association) made by the members inter se. Thus, a subsisting member on the date of the gift is not entitled qua member to claim an interest in the property but takes the property by reference to the rules of the society. A member who leaves the association by death or resignation will have no claim to the property, in the absence of any rules to the contrary. This approach was supported in an obiter pronouncement by Brightman J in Re Recher’s Will Trusts [1972] Ch 526:

inter se

Between themselves.