Introduction to Trusts

Introduction to trusts

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

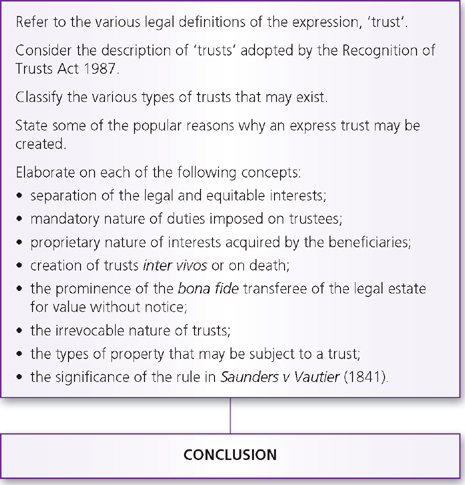

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

■ appreciate the main legal definitions of trusts

■ identify the essential characteristics of trusts

■ grasp the various types of trusts that exist

■ comprehend some of the more popular reasons for the creation of express trusts

2.1 Introduction

Constructing a comprehensive definition of a trust is extremely difficult, for a variety of trusts exist, and some of these do not fit into any of the traditional definitions. It is much simpler to describe a trust and identify its essential characteristics. In essence, the mechanism of the trust is an equitable device by which property is acquired and controlled by trustees for the benefit of others, called beneficiaries. These beneficiaries, subject to a few exceptions, are entitled to enforce the trust. For a variety of reasons, it may be prudent to prevent the entire ownership of property (legal and equitable) being vested and enjoyed by one person because such person would be in a position to dispose of the entire interest, perhaps for an inappropriate purpose such as gambling away the entire fund. A trust may be set up in order to advance this objective.

2.2 Trust concept

By origin, the trust was the exclusive product of the now defunct Court of Chancery, but since the Judicature Acts 1873 and 1875, trusts may be enforced in any court of law.

2.2.1 Definitions of trusts

The trust has been defined, or described, by many academics and, recently, by statute. The classic definition of a trust was stated by Underhill as follows:

QUOTATION

| ‘A trust is an equitable obligation, binding a person (called a trustee) to deal with property over which he has control (which is called the trust property) for the benefit of persons (who are called the beneficiaries or cestuis que trust) of whom he may himself be one, and any one of whom may enforce the obligation.’ | |

| A Underhill and D Hayton, Law of Trusts and Trustees (16th edn, Butterworths, 2002), p. 1 |

This definition does not include charitable and private purpose trusts, but Underhill was merely defining traditional private trusts. A private purpose trust is intended to benefit objects which do not have the capacity to enforce the trust (such as maintaining a grave in a cemetery), as distinct from benefiting society as a whole or the public at large. Charitable trusts are distinct from private trusts in many ways (see Chapter 12), and the Attorney General, as a representative of the Crown, is empowered to enforce such trusts on behalf of the public. Private purpose trusts (or trusts for imperfect obligations) in any event are considered anomalous and are exceptionally treated as valid. Underbill’s definition of a trust refers to an ‘equitable obligation’ in that originally the Lord Chancellor and later the Court of Chancery enforced moral obligations undertaken by trustees (feoffees) in the interests of natural justice and conscience. The definition refers to property under the ‘control’ of trustees. It is evident that the trustees have the legal title to property but the essence of a trust is that they are required to hold the property for the benefit of the beneficiaries. It is because of the fiduciary position of the trustees and the temptation to abuse their position that a number of duties are imposed on the trustees. Finally, the beneficiaries, by definition, are the persons who are entitled to enjoy the benefit of the trust property and who are given a locus standi to enforce the trust and to ensure that the trust property is properly administered.

fiduciary

A person whose judgment and skill is relied on by another.

Maitland defined a trust thus:

QUOTATION

| ‘When a person has rights which he is bound to exercise upon behalf of another or for the accomplishment of some particular purpose he is said to have those rights in trust for that other and for that purpose and he is called a trustee.’ | |

| F W Maitland, Equity: A Course of Lectures (ed. A H Chaytor and W J Whittaker, revd J Brunyate, Cambridge University Press, 2011) |

It may be noted that this is a vague definition of a trust, as Maitland admitted, but, on examination, it is not a definition at all, but a description of some of the elements of a trust.

In Lewin on Trusts a comprehensive definition set out by an Australian judge, Mayo J, in Re Scott [1948] SASR 193 was referred to in the text.

QUOTATION

| ‘The word “trust” refers to the duty or aggregate accumulation of obligations that rest upon a person described as trustee. The responsibilities are in relation to property held by him, or under his control. That property he will be compelled by a court in its equitable jurisdiction to administer in the manner lawfully prescribed by the trust instrument, or where there be no specific provision written or oral, or to the extent that such provision is invalid or lacking, in accordance with equitable principles. As a consequence the administration will be in such a manner that the consequential benefits and advantages accrue, not to the trustee, but to the persons called cestuis que trust, or beneficiaries, if there be any; if not, for some purpose which the law will recognise and enforce. A trustee may be a beneficiary, in which case advantages will accrue in his favour to the extent of his beneficial interest.’ | |

| Mayo, J quoted in L Tucker, N Le Poidevin, J Brightwell, Lewin on Trusts (Sweet & Maxwell, 2014) |

The American Restatement of the Law of Trusts (1959) declares:

QUOTATION

| ‘A trust … when not qualified by the word “charitable”, “resulting” or “constructive” is a fiduciary relationship with respect to the property, subjecting the person by whom the property is held to equitable duties to deal with the property for the benefit of another person, which arises as a result of a manifestation of an intention to create it.’ |

G Thomas and A Hudson in The Law of Trusts (Oxford University Press, 2004) offer a definition of a trust in this form:

QUOTATION

| The essence of a trust is the imposition of an equitable obligation on a person who is the legal owner of property (a trustee) which requires that person to act in good conscience when dealing with that property in favour of any person (the beneficiary) who has the beneficial interest recognised by equity in the property. The trustee is said to “hold the property on trust” for the beneficiary. There are four significant elements to the trust: that it is equitable, that it provides the beneficiary with rights in property, that it also imposes obligations on the trustee, and that those obligations are fiduciary in nature.’ |

The ‘equitable obligation’ that is referred to in Thomas and Hudson’s definition is a reference back to the historical origin of trusts which were recognised only by equity prior to the Judicature Act 1873. The obligation to carry out the terms of the trust is attached to the trustee to control his actions as a fiduciary and to allay the fears that he may be tempted to take the property or otherwise abuse his position. The trustee acquires the legal title to the property and the beneficiary, as an equitable owner, acquires the right to enjoy the property.

2.2.2 Recognition of Trusts Act 1987

Section 1 of the Recognition of Trusts Act 1987 declares that the term ‘trust’ possesses the characteristics detailed in Art 2 of the Hague Convention on the Recognition of Trusts, referred to in the Schedule to the Act:

SECTION

| ‘Section 1 | |

| For the purposes of this Convention, the term trust refers to the legal relationship created – inter vivos or on death – by a person, the settlor, when assets have been placed under the control of a trustee for the benefit of a beneficiary or for a specified purpose.’ |

inter vivos

During the lifetime or before death.

A trust has the following characteristics:

(a) the assets constitute a separate fund and are not a part of the trustee’s own estate;

(c) the trustee has the power and the duty, in respect of which he is accountable, to manage, employ or dispose of the assets in accordance with the terms of the trust and the special duties imposed upon him by law.

The reservation by the settlor of certain rights and powers and the fact that the trustee may himself have rights as a beneficiary are not necessarily inconsistent with the existence of a trust.

This description of a trust has been formulated by reference to the characteristics of a trust (these are discussed below).

2.2.3 Lord Browne-Wilkinson’s essential characteristics of a trust

In Westdeutsche Landesbank Girozentrale v Islington BC [1996] AC 669, HL (for facts, see Chapter 16), Lord Browne-Wilkinson identified four fundamental principles of trusts law the existence of which he considered uncontroversial:

JUDGMENT

| (i) Equity operates on the conscience of the owner of the legal interest. In the case of a trust, the conscience of the legal owner requires him to carry out the purposes for which the property was vested in him (express or implied trust) or which the law imposes on him by reason of his unconscionable conduct (constructive trust). (ii) Since the equitable jurisdiction to enforce trusts depends upon the conscience of the holder of the legal interest being affected, he cannot be a trustee of the property if and so long as he is ignorant of the facts alleged to affect his conscience, i.e. until he is aware that he is intended to hold the property for the benefit of others in the case of an express or implied trust, or, in the case of a constructive trust, of the factors which are alleged to affect his conscience. (iii) In order to establish a trust there must be identifiable trust property. The only apparent exception to this rule is a constructive trust imposed on a person who dishonestly assists in a breach of trust who may come under fiduciary duties even if he does not receive identifiable trust property. (iv) Once a trust is established, as from the date of its establishment the beneficiary has, in equity, a proprietary interest in the trust property, which proprietary interest will be enforceable in equity against any subsequent holder of the property (whether the original property or substituted property into which it can be traced) other than a purchaser for value of the legal estate without notice. These propositions are fundamental to the law of trusts and I would have thought uncontroversial.’ |

The reference to the ‘conscience’ of the trustee concerns the original assumption of jurisdiction by the Lord Chancellor for enforcing trusts. The trustee is treated as a fiduciary with special duties imposed on him. If they abuse their position as fiduciaries by receiving unauthorised profits they become trustees of those profits. This notion of conscience requires the trustees to be aware that they are acting with impropriety. It is evident that the trust is required to attach to identifiable property, except with regard to the liability to account as an accessory. Finally, Lord Browne-Wilkinson declares that a beneficiary under a trust acquires a proprietary interest in the trust property (i.e. a right in rem). The effect is that the beneficiary is entitled to recover the property in either its original or substituted form, except as against a bona fide transferee of the legal estate for value without notice (‘equity’s darling’).

in rem

A right that exists against the world at large as opposed to in personam.

ACTIVITY

| Compare Lord Browne-Wilkinson’s essential characteristics of a trust laid down in West-deutsche Landesbank Girozentrale v Islington BC [1996] with those laid down in the Recognition of Trusts Act 1987. |

2.3 Characteristics of a trust

The distinctive features of a trust are outlined below. It is submitted that an understanding of these features is a more practical way of recognising and distinguishing a trust from other concepts.

2.3.1 Trust property

Any existing property which is capable of being assigned may form the subject-matter of a trust. Thus, the trust property may take the form of ‘personalty’, such as chattels or debts enforceable at law (choses in action), or an interest in land called ‘realty’ (freehold or leasehold interest in land). Moreover, the nature of the trust property may vary throughout the trust. The property may take the form of realty which is sold and the proceeds of sale reinvested in shares.

chose(s) in action

These are personal, intangible property(ies) such as rights to have a loan repaid, the right to dividends from shares and intellectual property.

However, only subsisting property is capable of being the subject-matter of a trust. Accordingly, an expectancy or future property (such as a right under a will which has not vested because the testator is still alive) cannot be the subject-matter of a trust.

2.3.2 Separation of legal and equitable interests

The legal interest in property is the title which reflects the ‘indicia’ of ownership. The legal owner has the right to have his title to the property and the incidents of ownership respected by the rest of society. Thus he may enforce or protect his interest in the property through litigation. The equitable interest, on the other hand, is a right or an interest in property which, before the Judicature Acts of 1873 and 1875, was recognised solely by a Court of Chancery. The Judicature Acts effected a fusion of the administration of law and equity, so that in appropriate cases equitable principles may be applied in common law courts. The equitable title is the beneficial interest in property or the right to enjoy the property.

expectancy

These are rights that do not currently exist but may or may not exist in the future.

Generally, the trustee holds the legal title to property for the benefit of the beneficiary. The beneficiary enjoys the equitable interest. The rule is that whenever the two interests (legal and equitable) are separated, a trust is in existence. For example, T (a trustee) holds the legal title to shares in X Co (trust property) on trust for B, a beneficiary, absolutely. B acquires an equitable interest in the shares.

T(trustee with the legal title) → B(beneficiary with the equitable interest)

In addition, the same interests may be enjoyed jointly by the same persons under a trust. For example, T and B may hold the legal estate on trust for T and B equally.

T & B(legal interest) → T & B(equitable interest)

2.3.3 Sub-trusts

Sometimes the trustee may hold the equitable interest on behalf of a beneficiary. This would be the case where a beneficiary, who enjoys an equitable interest under a subsisting trust, creates a trust of his interest in favour of another, i.e. a beneficiary under a trust creates a sub-trust of his entire interest in favour of a sub-beneficiary. The effect of this arrangement is that the beneficiary under the original trust assigns his interest to the new beneficiary by way of a trust. In this situation the original beneficiary adopts the role of the settlor and trustee for the benefit of another:

T(legal owner – B(original equitable owner – C(sub-beneficiary or new equitable owner))

Indeed, it is possible for the original equitable owner to create a sub-trust and, at the same time, remain an equitable owner of trust property. This would be the position where the original equitable owner declares a trust of part of his equitable interest. For example, T (legal owner) holds on trust for B absolutely (equitable owner). B retains a life interest in the property and declares himself a trustee of the remainder for C absolutely.

The new arrangement may be illustrated as follows:

It should be noted that in respect of the sub-trust, B will have active duties to perform on behalf of his new beneficiary, C.

2.3.4 Obligatory

A trust is mandatory in nature. The trustees have no choice as to whether they may fulfil the intention of the settlor. Instead, the trustees are required to fulfil the terms of the trust as stipulated in the trust instrument and implied by rules of law. The beneficiaries are given a locus standi to ensure that the trustees carry out their duties (but note the anomalous nature of private purpose trusts – see Chapter 11).

locus standi

The right to be heard in court or other proceedings.

will

A document signed by the testator and attested by two or more witnesses which disposes of the testator’s assets on his death.

2.3.5 Inter vivos or on death

Trusts may be created either inter vivos (during the lifetime of the settlor) or on death, by will or on an intestacy (under the Administration of Estates Act 1925, as amended). An inter vivos trust may be created by deed or in writing other than by way of a deed, orally or by conduct. Irrespective of the form which the trust takes, the trust becomes effective from the date of the execution of the document or statement. On the other hand, trusts created by wills or on intestacies take effect on the death of the testator or person dying intestate.

intestacy

A person who dies without making a valid will. His estate devolves on those specified under the intestacy rules.

2.3.6 The settlor’s position

The settlor is the creator of an express trust. He decides the form that the trust property may take, the interests of the beneficiaries, the identity of the beneficiaries, the persons who will be appointed trustees and the terms of the trust. Indeed, he may appoint himself one of the trustees or the sole trustee. In short, the settlor is the author of the trust. But once the trust is created, the settlor, in his capacity as settlor, loses all control or interest in the trust property. Unless he has reserved an interest for himself, he is not entitled to derive a benefit from the trust property, nor is he allowed to control the conduct of the trustees. In other words, following the creation of a trust the settlor, in his capacity as settlor, is treated as a stranger in respect of the trust.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Bowden [1936] Ch 71 |

| The settlor, before becoming a nun and in order to undertake the vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, transferred property to trustees on trust for specified beneficiaries. Later, she changed her mind when she left the convent and attempted to reclaim the property for her own benefit. The court held that, since the trust was created, the claimant as settlor lost all interest in the property and therefore could not recover the property. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘the persons appointed trustees under the settlement received the settlor’s interest … and, immediately after it had been received by them, as a result of her own act and her own declaration … it became impressed with the trusts contained in the settlement.’ |

| Bennett J |

The settlor’s position vis-à-vis the trust is analagous to the position of a promoter (or shareholder) of a company and his relationship with the company. The well-known, fundamental rule in company law is that a company is an artificial legal person, distinct from its members. Thus, a company is capable of enjoying rights and is subject to duties which are generally not attributable to its members. In other words a company may own property, enter into contracts, sue and be sued and open and operate bank accounts in its own name. The rights and liabilities of the company are treated separately from the rights and duties of the members or shareholders. Accordingly, even if a company is controlled by one shareholder, the company and that shareholder are treated as distinct legal persons. This is known as the doctrine in Salomon v Salomon & Co Ltd [1897] AC 22. A company was formed to take over Mr Salomon’s business and the House of Lords ruled that, despite Mr Salomon holding 20,001 of the 20,007 shares issued by the company, the company and Mr Salomon were distinct legal entities. Lord Macnaghten expressed the general rule thus:

JUDGMENT

| ‘The company is at law a different person altogether from the subscribers to the memorandum; and, though it may be that after incorporation the business is precisely the same as it was before, and the same persons are managers, and the same hands receive the profits, the company is not in law the agent of the subscribers or trustee for them.’ |

The same general principle of independent legal personality of a company (or corporate veil) was affirmed by the Supreme Court in Prest v Petrodel Resources Ltd [2013] 2 AC 415. However, the corporate veil may be lifted in limited circumstances when the notion of separate legal personality is abused for the purpose of promoting some wrongdoing. The test was stated by Lord Sumption in Prest v Petrodel in the following manner:

JUDGMENT

| ‘I conclude that there is a limited principle of English law which applies when a person is under an existing obligation or liability or subject to an existing legal restriction which he deliberately evades or whose enforcement he deliberately frustrates by interposing a company under his control. The court may then pierce the corporate veil for the purpose, and only for the purpose, of depriving the company or its controller of the advantage that they would otherwise have obtained by the company’s separate legal personality. The principle is properly described as a limited one.’ |

2.3.7 The trustees’ position

The trustees bear the responsibility of controlling and managing the trust property solely for the benefit of the beneficiaries. This responsibility is treated as giving rise to a fiduciary relationship. Its characteristics are a relationship of confidence, trustworthiness to act for the benefit of the beneficiary and a duty not to act for his (the trustee’s) own advantage.

The trustees are the representatives of the trust. Owing to the opportunities to abuse their position the rules of equity were formulated to impose a collection of strict and rigorous duties on the trustees. Indeed, trustees’ duties are so onerous that they are not even entitled to be paid for their services as trustees, in the absence of authority.

Trustees are liable in their personal capacity for mismanaging the trust funds and in extreme cases may be made bankrupt, should they neglect their duties.

2.3.8 The beneficiaries’ position

The beneficiaries (as the owners of the equitable interest) are given the power to compel the due administration of the trust. They are entitled to sue the trustees and any third party for damages (joining the trustees in the action as co-defendants) for breach of trust. In addition, the beneficiaries may trace the trust property in the hands of third parties (see Chapter 16) with the exception of bona fide transferees of the legal estate for value without notice. Through this process the beneficiaries may be able to recover the trust property that was wrongly transferred to another or obtain a charging order representing their interests. The beneficiaries are given an interest in the trust property and are entitled to assign the whole or part of such interest to others. The beneficiaries are entitled to terminate the trust by directing the trustees to transfer the legal title to them, provided that they have attained the age of majority, and are compos mentis (mentally sound) and absolutely entitled to the trust property.

bona fide

In good faith.