Historical Outlines of Equity

Historical outlines of equity

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

■ understand the shades of meaning of the expression ‘equity’ as used over the centuries

■ comprehend the historical development and contribution of equity to English law

■ appreciate the nineteenth-century reforms responsible for the administration of law and equity

■ recognise the various maxims of equity

equity

That separate body of rules formulated and administered by the Court of Chancery prior to the Judicature Acts 1873/75 in order to supplement the deficiency in the rules and procedure at common law.

1.1 Introduction to equity

QUOTATION

| ‘Equity is the branch of law, which, before the Judicature Acts 1873 and 1875 was applied and administered by the Court of Chancery.’ | |

| F W Maitland, Equity: A Course of Lectures (ed. A H Chaytor and W J Whittaker, revd J Brunyate, Cambridge University Press, 2011) |

natural justice

Rules applied by the courts and other tribunals designed to ensure fairness and good faith and affording each party the opportunity to fairly state his case.

The system of equity includes that portion of natural justice which is judicially enforceable but which for various reasons was not enforced by the courts of common law. In this context the expression ‘natural justice’ is used in the broad sense of recognising and giving effect to justiciable rights of aggrieved parties based on principles of fairness and conscience that were not acknowledged by the common law courts. The common law system was perceived as being too formalistic and rigid in its outlook with the result that the potential rights of certain litigants were subject to abuse. The principles which gave effect to the rights of litigants and which were not recognised by the common law courts were known as equity.

Equity, unlike the common law, was not an independent system of legal rules. It did not stand alone. It presupposed the existence of the common law, which it supplemented and modified. The rules of equity were originally based on conscience and principles of natural justice, and were applied on a case-by-case basis. Where there were ‘gaps’ in the common law rules that created injustice to one or more of the parties, the rules of equity ‘filled in these gaps’. Thus it has been said that ‘Equity came to fulfil the law, not to destroy it.’ The two systems of rules were complementary to each other. The rules of equity were regarded as that portion of natural justice that was judicially enforceable but which for a variety of reasons was not enforced by the courts of common law. The effect was that although the rules of equity did not directly contradict the common law, the application of equitable rules was capable of producing an effect which was different from the common law solution. A modern example of the operation of equity is illustrated by Cresswell v Potter [1978] 1 WLR 255. In this case, a sale of land by a ‘poor and ignorant’ person (judge’s expression) at a substantial undervalue and without independent legal advice was regarded as an unconscionable bargain and the transaction was set aside.

common law

That part of the law of England and Wales formulated, developed and administered by the old common law courts. The rules that were originally applied by these courts were based on the common customs of this country.

1.1.1 Terminology

Originally, the expressions ‘equity’ or ‘rules of equity’ were synonymous with rules of justice and conscience. Individual Lords Chancellor did not consciously set out to develop a system of rules, but attempted in individual cases to achieve fairness and justice ad hoc. Accordingly, the principles originally applied by Lords Chancellor to determine disputes were based on rules of natural justice or conscience. These principles became known as equity.

ad hoc

For this purpose or individual cases.

Today, it would not be accurate to correlate ‘equity’ with ‘justice’ in the sense in which these expressions were used in medieval society. After the initial period of development the rules of equity became as settled and rigid as the common law had become. New equitable principles may not be created judicially, except within the parameters laid down by the courts over the centuries. Further, it is a myth to imagine that laying down a lax collection of principles by the courts in an effort to achieve fairness on a case-by-case basis will objectively fulfil the aim of justice in the broader sense of the word. The improved machinery for law reform has resulted in the increased willingness of Parliament to modernise the law in appropriate cases. The modern approach was refected by Bagnall J in Cowcher v Cowcher [1972] 1 All ER 943, thus:

JUDGMENT

| ‘I am convinced that in determining rights, particularly property rights, the only justice that can be attained by mortals, who are fallible and are not omniscient, is justice according to law; the justice which flows from the application of sure and settled principles to proved or admitted facts. So in the field of equity the length of the Chancellor’s foot has been measured or is capable of measurement. This does not mean that equity is past child-bearing; simply that its progeny must be legitimate – by precedent out of principle. It is well that this should be so; otherwise no lawyer could safely advise on his client’s title and every quarrel would lead to a law suit.’ |

1.1.2 Petitions to the Lord Chancellor

In the thirteenth century, the available writs covered a narrow umbrella of claims – even if a claim came within the scope of an existing writ, the claimant might not have gained justice before a common law court; for example in an action commenced by the writs of debt and detinue, the defendant was entitled to wage his law. This was a process whereby the defendant discharged himself from a claim by denying the claim on oath and calling 11 persons from his neighbourhood to swear that his denial was genuine. In addition, a great deal of unnecessary intricacies were attendant on the pleadings. The pleadings were drafted by experts, and the rule at this time was that an incorrect pleading invariably led to the loss of the claim. Moreover, damages was the only remedy available at law. There were numerous occasions when this remedy proved inadequate. If A proved that B had made a contract with him and had acted in breach of such contract, A was entitled to damages in the common law courts. But that may well have been inadequate satisfaction for A, who would rather have the contract performed than be solaced with damages. The subject-matter of the breach of contract may well have had inherent unique qualities such as a contract for the sale of land or a painting. What A wanted was an order from the court compelling B to perform his duties under the contract, such as an order for specific performance that was granted initially by the Chancellor and subsequently by a court of equity. Similarly, C’s conduct (D’s neighbour) or use of his premises may have seriously inconvenienced D’s use and enjoyment of his premises. The award of damages at common law was inadequate for D needed a remedy of an injunction to forbid C from continuing with his unlawful activity. Such a remedy was originally granted by the Chancellor and became integrated within the jurisdiction of the court of equity.

subpoena

The forerunner of the witness summons. It was a writ issued in an action requiring the addressee to be present in court at a specified date and time. Failure to attend without good cause is subject to a penalty.

An aggrieved claimant was entitled to petition the King in Council, praying for relief. These petitions were dealt with by the Lord Chancellor, who was an ecclesiastic well versed in Canon law. Later on, the petitions were addressed directly to the Lord Chancellor, who dealt personally with the more important cases. Eventually the Chancellor and staff formed a court called the Court of Chancery to deal with the overwhelming number of petitions for equitable assistance.

1.1.3 Procedure in Chancery

The petition was presented by way of a bill fled by the claimant. Since proceedings were not commenced by writ as in the common law courts, there was never any strict procedure to be followed. The intervention by the Lord Chancellor (creating new rights and remedies) did not need validation by the pretence or fiction adopted by the common law courts in declaring the law from time immemorial, but instead considered each case on its merits and applied principles in accordance with his views of justice and fairness.

affidavit

A written, signed statement made on oath or subject to a solemn affirmation.

In appropriate cases a subpoena would be served on the defendant to compel his appearance to attend and answer the petition. The defendant was required to draft his answers on oath, called ‘interrogatories’.

in personam

An act done or right existing with reference to a specific person as opposed to in rem (or in the thing).

Usually the evidence was given on affidavit so that proceedings were confined to hearing legal arguments on both sides, but occasionally when the testimony of a witness (including the parties) was required to be received in the court, the witness would be required to testify on oath and be subjected to cross-examination by the Chancellor and the opposing party. This process was inquisitorial in nature and permitted the Chancellor (and the Court of Chancery) to marshal the facts freed from the formalistic and rule-driven mode of admitting the facts that was adopted by the common law courts.

The relevant decree of the court was issued in the name of the Chancellor and acted ‘in personam’ on the defendant. In this context the expression ‘in personam’ refers to the process in equity of enforcing the decrees of the Chancellor and the court of equity. The orders of the Chancellor were addressed to the defendant personally to comply with the order. The sanction for disobeying the Chancellor’s decrees was imprisonment for contempt of court.

contempt of court

A disregard of the authority of the court. This is punishable by the immediate imprisonment of the offender.

The principles of equity were even applicable irrespective of whether the defendant was within or outside the jurisdiction. Lord Selbourne LC in Ewing v Orr Ewing (No 1) [1883] 9 App Cas 34, said:

QUOTATION

| ‘The courts of Equity in England are, and always have been, courts of conscience, operating in personam and not in rem; and in the exercise of this personal jurisdiction they have always been accustomed to compel the performance of contracts and trusts as to subjects which were not … within the jurisdiction.’ | |

1.1.4 The trust – a product of equity

One of the most important contributions of equity was in the field of the ‘use’ (the predecessor to the ‘trust’). The ‘use’ was a mode of transferring property to another (e.g. B) to hold to the ‘use’ or for the benefit of another or others (e.g. C or D and E).

The ‘use’ (forerunner to the trust) was created in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, for a variety of reasons:

1. Crusades – a landowner (X) who went on the crusades and, fearing for his life and the consequences of a succession of his wealth, might adopt the strategy of conveying land to his friend (B) to hold for the use of a nominated person or group of persons (X’s wife and children) whilst he was away. B was referred to as a feoffee to use (today, a trustee) and X’s wife and children were originally referred to as the cestuis que use or trust or, in modern parlance, ‘benefciaries’. In this example, B acquired the legal title to land on the understanding that he controlled and used it for the benefit of the stated purpose. The common law recognised and gave effect only to the legal title acquired by B and did not recognise the promise made by him. Accordingly, the common law treated B as the absolute owner of the property, unrestricted by the assurance that B gave to X. If B defaulted on the promise and claimed the property as his own, equity intervened in order to uphold the promise. Before the Wills Act 1540, wills were not recognised at common law.

2. Ownership by Franciscan monks – as a result of their vow of poverty, a community of Franciscan monks might transfer the legal title to land to C and D to the use or benefit of the monks at a stated monastery. The effect was that the monks were able to enjoy the benefit of land ownership and at the same time maintain their vows. Equity recognised the interests of the monks.

3. By far the most important reason for the creation of a use was to avoid the feudal incidents inherent in land ownership, such as wardship and escheat (no heir). Feudal incidents were a form of taxes levied by a landlord on his tenant. Wardship involved a fine payable to the landlord on the occasion of a tenant dying leaving a male, infant heir. Escheat occurred when a tenant died without leaving an heir. The tenant’s estate in these circumstances reverted back to the landlord by way of escheat. These burdens were avoided if the land was vested in a number of feoffees to use (or trustees). The feoffees were unlikely to die together or without heir. Those who died could be replaced. The feoffees to use were required to hold the land for the benefit of the cestui que trust (or beneficiary) and the court of equity recognised and gave effect to the interest of the cestui que trust.

feoffee

An expression that was used originally to describe the trustee. The full title was ‘feoffee to use’.

feudal incidents

Penalties or taxes that were payable in respect of the transfer of land.

cestui(s) que trust

An expression used originally to describe the benefciary(ies) under a trust.

Thus, a tenant, A, might transfer his land by the appropriate common law conveyance to B, who undertook to hold it for the benefit of (or to the ‘use’ of) A and his heirs. The common law courts did not recognise A’s intended beneficial interest (nor his heirs). The legal ownership vested in the feoffee, B, was everything. He had control of the property and an interest that was recognised by the common law courts. If B refused to account to his cestuis que use, A and his heirs, for the profits, or wrongfully conveyed the estate to another, this was treated merely as an immoral breach of confidence on the part of B. The common law did not provide any redress, nor did the law acknowledge any right in A and his heirs to the enjoyment of the land.

1.1.5 The Chancellor’s intervention

The non-recognition of the right of enjoyment of the land on the part of A and his heirs had the potential for stultifying the practice of putting lands in use, had there been no alternative means of protecting the cestui que use. From about 1400 the Lord Chancellor stepped in and interceded on behalf of the cestui que use. He did not interfere with the jurisdiction of the common law courts because the legal title was vested in the feoffees, and this title was recognised and given effect by the common law courts. The Chancellor regarded his role as that of ensuring that the feoffee acted honestly and with morality. In accordance with the principle that equity acts in personam (against the wrongdoer personally), the Chancellor proceeded against feoffees who disregarded the moral rights of the cestui que use. The ultimate sanction for disobedience of the Chancellor’s order was imprisonment or sequestration of the defendant’s property until the order was complied with. In other words, the wrong that a rogue feoffee committed was a breach of contract or understanding, but it was a breach for which, at that time, no remedy existed in the common law courts. The enforceability of contracts was still undeveloped and, in any event, the rules of privity of contract would have precluded a remedy to the cestui que use.

1.1.6 Duality of ownership

The Chancellor’s intervention in the context of the ‘use’ of land (a concept which initiated with respect to money) created the notion of duality of land ownership, which in turn led to duality of ownership of other types of property. The method of intervention adopted by the Chancellor was to recognise that the feoffee had acquired the legal and inviolable title to the land or other property, but insisted that the feoffee carry out the terms of the understanding or purpose of the transfer as stipulated by the transferor. This required the feoffee to hold the property exclusively for the specified cestui(s) que trust (or beneficiary) rather than for his benefit. Thus, equity insisted that the feoffee scrupulously observed the directions imposed upon him. In other words, the Chancellor, like the common law judges, acknowledged that the feoffee was the owner of the property but the cestui que use was regarded as the true owner in equity. The former had the legal title but the latter acquired the equitable ownership in the same property.

Position of the feoffee

At law, the feoffee was regarded as the absolute owner of the property and liable to the incidents of tenure. ‘Tenure’ was an aspect of the feudal system of land ownership whereby the king was the owner of all land and his subjects held estates by some tenure. Tenures were classified in accordance with the nature of the ‘incidents’ or services which the tenant was required to render for his holding. In return the lord was required to protect those who acquired estates from him. For example, the tenant might be required to provide a fraction of the lord’s military force, known as ‘knight service’, or to say masses for the soul of the grantor, known as ‘frankalmoign’. The common law courts recognised only the legal title to property.

tutor tip

‘The historical foundation of equity has a significant impact in understanding the modern law of trusts.’

If the feoffee was required to hold the land for the benefit of the cestui que trust and the common law courts failed to acknowledge the possibility that the cestui que trust may be entitled to enjoy the property, the feoffee might be entitled to commit a fraud on thecestui que trust by simply ignoring his interest. But in Chancery the feoffee was compelled to carry out the obligations created by the use, i.e. to recognise the interest of the cestui que trust and act for his benefit. Moreover, the Chancery developed the rule that any third parties who took the land from the feoffee with knowledge of the existence of the use was bound by the use. Hence the rule which subsists today that the use (or trust) is valid against the world, except a bona fide transferee of the legal estate for value without notice.

Position of the cestui que use

This individual’s interest was not recognised at law but was granted recognition in equity and thus acquired an equitable interest. He was entitled to petition the Court of Chancery to have his interest and rights protected against the feoffee and the world, except the bona fide transferee of the legal estate for value without notice.

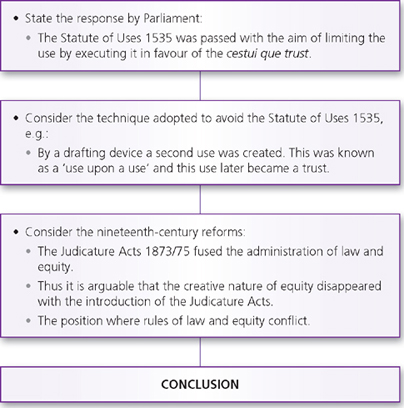

1.1.7 Statute of Uses 1535

The principal objection to the use was the loss to the king of revenue that arose from the incidents of tenure. The king needed all the revenue he could muster during the sixteenth century and the growth of the use hindered this process. Ultimately, the Statute of Uses 1535 was passed to reduce the scope of the use.

The statute provided that:

SECTION

| ‘Where any person(s) shall be seised of any lands or other hereditaments to the use, confidence or trust of any person(s), in every such case such person(s) that shall have any such use, confidence or trust in fee simple, fee tail, term of life or for years or otherwise shall stand and be seised, deemed and adjudged in lawful seisin, estate and possession of and in the same lands in such like estates as they had or shall have in the use.’ |

hereditaments

Refers to the two types of real properties that exist, namely corporeal and incorporeal. Corporeal hereditaments are visible and tangible objects such as houses and land, whereas incorporeal hereditaments refer to intangible objects attached to the land, such as easements and restrictive covenants.