Eleven

CHAPTER ELEVEN

ACADEMIC ANTISCIENCE

Stupidity is the twin sister of reason: It grows most luxuriously not on the soil of virgin ignorance, but on soil cultivated by the sweat of doctors and professors.

—WITOLD GOMBROWICZ, 1988

Science and ideology are incompatible.

—JOHN S. RIGDEN AND ROGER H. STUEWER, 2004

Once the liberal democracies had prevailed against fascism and communism—vanquishing, with the considerable help of their scientific and technological prowess, the two most dangerously illiberal forces to have arisen in modern times—you might think that academics would have investigated the relationship between science and liberalism. The subject had come up before. In 1918 the president of Stanford University suggested that “the spirit of democracy favors the advance of science.” In 1938 the medical historian Henry E. Sigerist allowed that while it might be “impossible to establish a simple causal relationship between democracy and science and to state that democratic society alone can furnish the soil suited for the development of science,” it could hardly “be a mere coincidence…that science actually has flourished in democratic periods.” In 1946, the historian of science Joseph Needham argued that “there is a distinct connection between interest in the natural sciences and the democratic attitude,” such that democracy could “in a sense be termed that practice of which science is the theory.” Inquiring into why this might be so, the Columbia University sociologist Robert K. Merton considered, as a “provisional assumption,” that scientific creativity benefits from the increased number of personal choices found in liberal-democratic nations. “Science,” he wrote, “is afforded opportunity for development in a democratic order which is integrated with the ethos of science.” In 1952, Talcott Parsons of Harvard argued that “only in certain types of society can science flourish, and conversely without a continuous and healthy development and application of science such a society cannot function properly.” As befits scholarly inquiry, the tenor of these investigations was modest, the researchers cautioning that the subject was complex and their findings preliminary. Bernard Barber, a specialist in the ethics of science, portrayed the relationship this way:

Examination will show that certain “liberal” societies—the United States and Great Britain, for example—are more favorable in certain respects to science than are certain “authoritarian” societies—Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. We say that the latter countries are “less favorable” we do not say that science is “impossible” for them. This is not a matter of black-and-white absolutes but only of degrees of favorableness among different related societies.

A good start, you might think; something to build on. But instead, academic discourse took a radical turn from which it has not yet fully recovered. Rather than investigate how science interacts with liberal and illiberal political systems, radical academics began challenging science itself, claiming that it was just “one among many truth games” and could not obtain objective knowledge because there was no objective reality, just a welter of cultural, ethnic, or gendered ways of experiencing reality. From this perspective what are called facts are but intellectual constructions, and to suggest that science and liberalism benefit each other is to indulge in “the naive and self-serving, or alternatively arrogant and conceited, belief that science flourishes best, or even can only really flourish, in a Western-style liberal democracy.”

These recondite theories went by a variety of names—deconstructionism, multiculturalism, science studies, cultural studies, etc.—for which this book employs the umbrella term postmodernism. They became so popular that generations of educators came to believe, and continue to teach their students today, that science is culturally conditioned and politically suspect—the oppressive tool of white Western males, in one formulation. Teachers—some of them—loved postmodernism because, having dismissed the likes of Newton and Darwin as propagandists with feet of clay, they no longer had to feel inferior to them but became their ruthless judges. Students—many of them—loved postmodernism because it freed them from the burden of actually having to learn any science. It sufficed to declare a politically acceptable thesis—say, that a given thinker was “logocentric” (a fascist epithet aimed at those who employ logic)—then lard the paper with knowing references to Marx, Martin Heidegger, Jacques Derrida, and other heroes of the French left. The process was so easy that computers could do it, and did: Online “postmodernism generators” cranked out such papers on order, complete with footnotes.

It seemed harmless enough at first. The postmodernists were viewed as standing up for women and minorities, and if they wanted the rest of us to prune our language a bit to make it politically correct, that seemed fair enough at a time when many white males were still calling women “girls” and black men “boys.” Not until postmodernists began gaining control of university humanities departments and denying tenure to dissenting colleagues did the wider academic community inquire into what the movement was and where it had come from. What they found were roots in the same totalitarian impulses against which the liberal democracies had so recently contended.

An early sally in the postmodernist campaign came in 1931, when a communist physicist named Boris Hessen prepared a paper for the Second International Congress of the History of Science, in London, interpreting Newton’s Principia as a response to the class struggles and capitalistic economic imperatives of seventeenth-century England. In it, Hessen deployed three tools that became indispensable to his radical heirs. First, the “great man” under consideration—in this case Newton—is reduced to an exemplification of the cultural and political currents in which he lived and on which he is depicted as bobbing along like a wood chip on a tide: “Newton was a child of his class.” Second, any facts the great man may have discovered are declared to be not facts at all but “useful fictions” that gained status because they promoted the interests of a prevailing social class: “The ideas of the ruling class…are the ruling ideas, and the ruling class distinguishes its ideas by putting them forward as eternal truths.” Finally, the great man’s lamentable errors and hypocrisies, and those of the society to which he belonged, are brought to light through the application of Marxist-Leninist or some other form of illiberal analysis aimed at reclaiming science for “the people”: “Only in socialist society will science become the genuine possession of all mankind.”

Ordinarily a clear writer, Hessen couched his London paper in obfuscatory jargon, declaring it his central thesis to demonstrate “the complete coincidence of the physical thematic of the period which arose out of the needs of economics and technique with the main contents of the Principia.” Put into plain English, this says that the economic and technological currents of Newton’s day completely dictated the contents of the Principia—that the noblemen and tradesmen of sixteenth-century England got what they wanted, which for some reason was a mathematically precise statement of the law of gravitation, written in Latin. Hence the need for obscurantist rhetoric: Had Hessen’s thesis been clearly stated, it would have read like a joke.

Which, in grim reality, it appears to have been. Loren R. Graham, a historian of science at MIT and Harvard who has written widely on Soviet science, looked into the Hessen case in the nineteen eighties. He was puzzled by the fact that this dedicated communist, whose London paper was a model of Marxist analysis, was soon thereafter arrested, dying in a Soviet prison not long after his fortieth birthday. Why, Graham wondered, had this happened?

What he found was disturbing. Hessen’s communist credentials were indeed impressive. He had been a soldier in the Red Army, an instructor of Red Army troops, and a student at the Institute of Red Professors in Moscow. His scientific credentials were equally solid. A gifted mathematician, he studied physics at the University of Edinburgh and then at Petro-grad before becoming a professor of physics at Moscow University. And yet, Graham found, by the time Hessen “went to London in the summer of 1931 he was in deep political trouble.”

The cause of the trouble was science. As a physicist, Hessen taught quantum mechanics and relativity, but neither of these hot new disciplines comported with Marxist ideology. Marxism is strictly deterministic—full of “iron laws” of this and that—whereas quantum mechanics incorporates the uncertainty principle and makes predictions based on statistical probabilities. Relativity is deterministic but was the work of Einstein, who came from a bourgeois background and, even worse, had taken to writing popular essays about religion that showed him to be something of a deist rather than a politically correct atheist. Had Hessen been a cynic he might have faked his way through the conflict, but being an honest communist he stood his ground. He implored his comrades to criticize the social context of relativity and quantum mechanics if they liked, and to reject the personal philosophies of Einstein and other scientists as they saw fit, but not to banish their science—because the validity of a scientific theory has little or nothing to do with the social or psychological circumstances from which it arises. In a way his position resembled that of Galileo, a believing Christian who sought to save his church from hitching its wagon to an obsolete cosmology. As a faithful Marxist, Hessen tried to dissuade the party from continuing to oppose relativity and quantum mechanics, since to do so would blind students to the brightest lights in modern physics.

For his trouble, Hessen was denounced by Soviet authorities as a “right deviationist,” meaning a member of the bourgeoisie who fails to identify with the proletariat (his father was a banker), and as an “idealist” who had strayed from Marxist-Leninist determinism—which Marx and Lenin had learned from popular books about nineteenth-century science and then enshrined in the killing jar of their ideology. To keep an eye on him, the party had Hessen chaperoned in London by a Stalinist operative, Arnost Kooman, who just three months earlier had published an article declaring that

Comrade Hessen is making some progress, although with great difficulty, toward correcting the enormous errors which he, together with other members of our scientific leadership, have committed. Nonetheless, he still has not been able to pose the issue in the correct fashion, in line with the Party’s policy.

Hessen evidently hoped that his London paper would awaken the party to its folly by demonstrating that a social-constructivist analysis could be made even of Newton. Marxists accepted the validity of Newtonian physics, even though Newton lived in a capitalist England. So, therefore, should relativity and quantum mechanics be acceptable, regardless of their alleged political infelicities. Writes Graham:

The overwhelming impression I gain from the London paper is that Hessen had decided “to do a Marxist job” on Newton in terms relating physics to economic trends, while imbedding in the paper a separate, more subtle message about the relationship of science to ideology. He must have realized that by interpreting Newton in elementary Marxist economic terms, he could accomplish two important goals: first of all, he could demonstrate his Marxist orthodoxy, something being seriously questioned by his radical critics back in the Soviet Union; second, he could, by implication, defend science against ideological perversion by pointing to the need to separate the great merit of Newton’s accomplishments in physics from both the economic order in which they arose and the philosophical and religious conclusions which Newton and many other people drew from them.

If so, Hessen’s talk represented a scientist’s last desperate effort to preserve his life and his Marxist faith by exposing the absurdity of the party line. It failed, and Hessen was crushed. Yet his paper lived on, through decades of heedless scholarship on the part of radical academics who neither got the joke nor much cared about the fate of its author. Thousands of academic papers were published supporting precisely the points that Hessen had lampooned—that science is socially conditioned and ought to be subordinated to state control. Many teachers and students today continue to believe that scientific findings are politically contaminated and that there is no objective reality against which to measure their accuracy. In the postmodernist view any text, even a physics paper, means whatever the reader thinks it means. What matters is to be politically correct. The term comes from Mao’s Little Red Book.

The postmodern assault on science involved two main campaigns. One was to undermine language—to “deconstruct” texts—by claiming that what a scientist or anybody else writes is really about the author’s (and the reader’s) social and political context. Central figures in this effort included the German philosopher Martin Heidegger, the French philosopher Jacques Derrida, and the Belgian literary critic Paul de Man. The other campaign took on science more directly, as a culturally conditioned myth unworthy of respect. Here an influential figure was the Austrian philosopher Paul Feyerabend, who drew on the relatively liberal works of Thomas Kuhn and Karl Popper.

Derrida got the term “deconstruction” from Heidegger (who got it from a Nazi journal edited by Hermann Göring’s cousin, and used it to advocate the dismantling of ontology, the study of the nature of being) but found it difficult to define: “A critique of what I do is indeed impossible,” Derrida declared, thus rendering his work immune to criticism. In essence, deconstructionism demands that the knowing reader tease out the meanings of texts by discerning the hidden social currents behind their words, emerging with such revelations as that Milton was a sexist, Jefferson a slave driver, and Newton a capitalist toady.

The doctrines of Heidegger and Derrida were imported into America by de Man, who as a faculty member at Yale became, in the estimation of the literary critic Frank Kermode, “the most celebrated member of the world’s most celebrated literature school.” His was the appealing story of an impoverished intellectual who had fought for the Resistance during the war but was too modest to say much about it (except that he had “come from the left and from the happy days of the Front populaire”), was discovered by the novelist Mary McCarthy and taken up by New York intellectuals while working as a clerk in a Grand Central Station bookstore, and went on to become one of America’s most celebrated professors, demolishing stale shibboleths with proletarian frankness. “In a profession full of fakeness, he was real,” declared Barbara Johnson, famous for having celebrated deconstructionism in a ripe sample of its own alogical style:

Instead of a simple “either/or” structure, deconstruction attempts to elaborate a discourse that says neither “either/or,” nor “both/and” nor even “neither/nor,” while at the same time not totally abandoning these logics either. The very word deconstruction is meant to undermine the either/or logic of the opposition “construction/ destruction.” Deconstruction is both, it is neither, and it reveals the way in which both construction and destruction are themselves not what they appear to be.

However, de Man was a fake. Soon after his death in 1983, a young Belgian devotee of deconstruction discovered that de Man, rather than working with the Resistance and coming “from the left,” had been a Nazi collaborationist who wrote anti-Semitic articles praising “the Hitlerian soul” for the pro-Nazi journal Le Soir. Moreover he was a swindler, a biga-mist, and a liar, who had ruined his father financially then fled to America, promising to send for his wife and three sons when he found work but choosing instead to marry one of his Bard College students.

When these discomfiting facts emerged, Derrida came to his friend de Man’s defense but in doing so inadvertently called attention to deconstructionism’s moral abstruseness. “The concept of making a charge itself belongs to the structure of phallogocentrism,” Derrida wrote dismissively. Nor was he alone in flying to the defense of de Man—who had presciently exonerated himself in advance, writing, in a 1979 study of Rousseau, “It is always possible to excuse any guilt, because the experience always exists simultaneously as fictional discourse and as empirical event and it is never possible to decide which one of the two possibilities is the right one.” Years later, radical academics were still teaching de Man as if he were something other than a liar, a cheat, and a Nazi propagandist. As Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont remind us, in their book Fashionable Nonsense, “The story of the emperor’s new clothes ends as follows: ‘And the chamberlains went on carrying the train that wasn’t there.’”

The foundations of radical academic thought were further undermined when disquieting evidence came to light concerning Heidegger, the philosopher whose work stood at the headwaters of Derrida’s deconstructionism, Jean-Paul Sartre’s existentialism, and the structuralism and poststructuralism of Claude Levi-Strauss and Michel Foucault. Regarded in such circles as the greatest philosopher since Hegel, Heidegger celebrated irrationalism, claiming that “reason, glorified for centuries, is the most stiff-necked adversary of thought.” He flourished in wartime Germany, being named rector of Freiburg University just three months after Hitler came to power. The postmodernist party line was that Heidegger might have flirted with Nazism but had been a staunch defender of academic freedom. In 1987, a former student of Heidegger’s found while searching the war records that Heidegger had joined the Nazi party in 1933 and remained a dues-paying member until 1945—signing his letters with a “Heil Hitler!” salute, declaring that der Führer “is the German reality of today, and of the future, and of its law,” and celebrating what he called the “inner truth and greatness of National Socialism.”

As might be expected of a dedicated Nazi holding a prominent university position, Heidegger worked enthusiastically to exclude Jews from academic life. He saw to it that the man who had brought him to Freiburg University—his former teacher Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology—was barred from using the university library because he was Jewish. He broke off his friendship with the philosopher Karl Jaspers, whose wife was Jewish; secretly denounced his Freiburg colleague Hermann Staudinger, a founder of polymer chemistry who would win the Nobel Prize in 1953, after learning that Staudinger was helping Jewish academics hang on to their jobs; and scotched the career of his former student Max Müller by informing the authorities that Müller was “unfavorably disposed” to Nazism. Heidegger lied about all this after the war, testifying to a de-Nazification committee in 1945 that he had “demonstrated publicly my attitude toward the Party by not participating in its gatherings, by not wearing its regalia, and, as of 1934, by refusing to begin my courses and lectures with the so-called German greeting [Heil Hitler!]”—when in fact that is exactly how he started his lectures, for as long as Hitler remained alive. In a similarly revisionist vein, Heidegger rewrote his 1935 paean to the “inner truth and greatness of National Socialism,” making it appear to have been an objection to scientific technology—an alteration that he repeatedly thereafter denied having made.

Particularly distressing, considering the subsequent spread of Heidegger’s fame through the American academic community, was his attitude toward the relationship of universities to the political authorities. Upon becoming rector of Freiburg, Heidegger declared that universities “must be…joined together with the state,” assuring his colleagues that “danger comes not from work for the State”—an astounding thing to say about the most dangerous state ever to have arisen in Europe—and urging students to steel themselves for a “battle” which “will be fought out of the strengths of the new Reich that Chancellor Hitler will bring to reality.” Suiting his actions to his words, Heidegger changed university rules so that its rector was no longer elected by the faculty but rather appointed by the Nazi Minister of Education—the same Dr. Rust who in 1933 decreed that all students and teachers must greet one another with the Nazi salute. Heidegger was rewarded by being appointed Führer of Freiburg University, a step toward what seems to have been his goal of becoming an Aristotle to Hitler’s Alexander the Great.

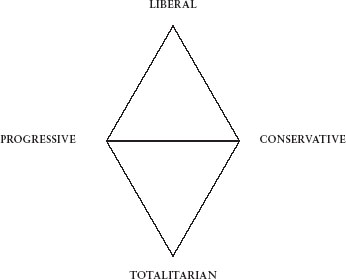

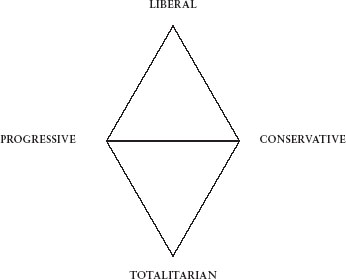

These and other revelations about the fascist roots of the academic left, although puzzling if analyzed in terms of a traditional left-right political spectrum, make better sense if the triangular diagram of socialism, conservatism, and liberalism is expanded to form a diamond:

Such a perspective reflects the fact that liberalism and totalitarianism are opposites, and have an approximately equal potential to attract progressives and conservatives alike. (Try guessing who, for instance, said the following: “Science is a social phenomenon…limited by the usefulness or harm it causes. With the slogan of objective science the professoriate only wanted to free itself from the necessary supervision of the state.” Lenin? Stalin? It was Hitler, in 1933.) The diagram also suggests why American liberals did at least as much as conservatives to expose the liabilities of communism, even when the USSR and the United States were wartime allies. In 1943, two liberal educators, John Childs and George Counts, cautioned their colleagues that communism “adds not one ounce of strength to any liberal, democratic or humane cause; on the contrary, it weakens, degrades or destroys every cause that it touches.” The following year, the liberal political scientists Evron Kirkpatrick and Herbert McClosky sought to correct procommunist sympathies among leftist academics by pointing out similarities between the Nazi and communist regimes—e.g., that both prohibited free elections, freedom of speech, and freedom of the press; were dominated by a single political party whose views were broadcast by an official propaganda network and enforced by state police; and were dedicated to expansion of their power by force. Because liberalism is diametrically opposed to totalitarian rule, these and many other liberals were alert to fallacies of illiberal rule that escaped those leftists and rightists whose focus on promised results blinded them to present dangers.

How did academics fall victim to authoritarian dogma? The story centers on the traumas that befell France between the two world wars. The Great War left France with over a million dead, a million more permanently disabled, and a faltering economy. The Great Depression—made worse by Premier Pierre Laval’s raising taxes and cutting government spending—brought the economy to its knees, while increases in immigration, intended to bolster France’s war-depleted workforce, spurred resentment among workers who complained that foreigners were claiming their jobs. These woes were then capped by the unique humiliations of France’s rapid surrender to Hitler’s army and its establishment of the collaborationist Vichy government. A consensus arose among French academics that democracy was bankrupt and socialism their salvation. Some went over to the Nazis, who had the temporary advantage of seeming to be the winning side. Others adhered to communism, which became the winning side on the Eastern Front and had gained respectability by virtue of the fact that many members of the French Resistance were communists. The resulting clash of right-wing and left-wing French intellectuals drove political dialogue toward illiberal intemperance. As the social scientist Charles A. Micaud observes:

A counter-revolutionary extreme right and a revolutionary extreme left, pitted against each other, emphasized the respective values of authority and equality at the expense of liberty…. Each coalition was kept together, not by positive agreement on a program, but by the fear inspired by the other extreme.