Duties and Powers of Trustees

Duties and powers of trustees

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

■ identify the trustees’ fiduciary duties including the duty to avoid making profits from the trust

■ define the standard of care imposed on trustees in the execution of their office

■ understand the scope of the trustees’ powers of delegation of duties

■ comprehend the limits regarding exclusion clauses designed to protect trustees

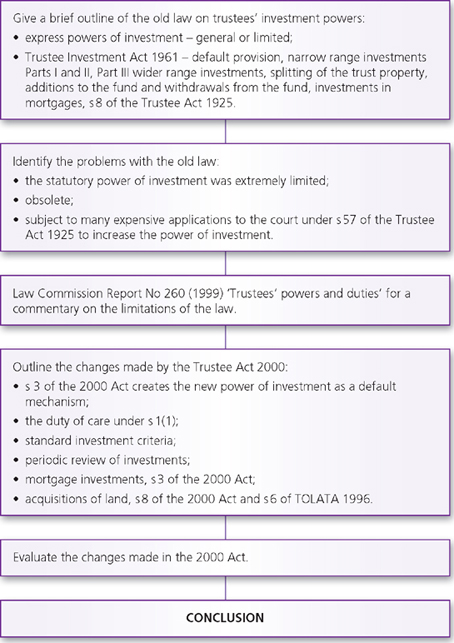

■ appreciate the changes made by the Trustee Act 2000 concerning the trustees’ power of investment of trust funds

■ understand the trustees’ powers of maintenance and advancement under ss 31 and 32 of the Trustee Act 1925

14.1 Introduction

The office of trustee is subject to a wide-ranging group of duties. A trustee has control of the trust property and is regarded as a fiduciary and, on that basis, owes a collection of special duties to the beneficiaries. The overriding obligation of the trustee is to act in the best interests of all the beneficiaries and not to allow his interests to conflict with his duties; see Chapter 8. The list of duties discussed in this chapter is not intended to be exhaustive. The trustees’ primary duties are to obey the terms of the trust and, subject thereto, to act for the benefit of the beneficiaries. It will become apparent that not only does the trustee owe a duty to all of the beneficiaries, but that he is under a duty to act fairly and impartially between them.

It will readily become apparent that the rules relating to the duties of the trustees are inextricably interwoven with other areas of trusts law, such as the powers of trustees, the liability of trustees for breach of trust and the remedies of the beneficiaries (see Chapter 16).

Trustees are endowed with a variety of powers in order to equip them with the discretion to respond to unforeseen or changed circumstances since the creation of the trust. It is imperative that the trustee identify and act in accordance with the source and scope of a power. Where a particular power does not exist and the trustee acts on the erroneous belief that it does, he may be in breach of trust.

The duties and powers of trustees have been laid down by the common law as modified by the trust instrument and statute.

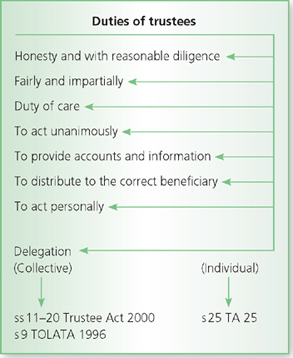

14.2 Duties of trustees

The duties of a trustee are varied and extremely onerous. They are required to be executed with the utmost diligence and good faith. Otherwise he will be liable for breach of trust. The primary duty of the trustee is to comply with the terms of the trust and, subject thereto, to act in the best interests of the beneficiaries. In order to carry out these duties, the trustee is invested with a variety of powers and discretions which are required to be exercised for the benefit of the beneficiaries.

14.2.1 Duty and standard of care at common law

Throughout the administration of the trust the trustee is required to exhibit an objective standard of skill as would be expected from an ordinary prudent man of business. In the case of a power of investment the duty would be exercised so as to yield the best return for all the beneficiaries, judged in relation to the risks inherent in the investments and the prospects of the yield of income and capital appreciation. The classical statement of the rule was laid down by Lord Watson in Learoyd v Whiteley (1887) 12 AC 727:

JUDGMENT

| ‘As a general rule the law requires of a trustee no higher degree of diligence in the execution of his office than a man of ordinary prudence would exercise in the management of his own private affairs.’ |

The courts will have regard to all the circumstances of each case in order to ascertain whether the trustees’ conduct fell below the standard imposed on such persons.

In considering the investment policy of the trust, the trustees are required to put on one side their own personal interests and views. They may have strongly held social or political views. They may be firmly opposed to any investments in companies connected with alcohol, tobacco, armaments or many other things. In the conduct of their own affairs, trustees are free to abstain from making any such investments. However, in performance of their fiduciary duties, if investments of the morally reprehensible type would be more beneficial to the beneficiaries than other investments, the trustees must not refrain from making the investments by reason of the views that they hold. Trustees may even act dishonourably (though not illegally), such as accepting a subsequent higher offer for the sale of trust property, if the interests of their beneficiaries require it.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Buttle v Saunders [1950] 2 All ER 193 Trustees struck a bargain for the sale of trust property. This was not legally binding, but the court held that they were under a duty to consider and explore a better offer received by them. |

CASE EXAMPLE

| Cowan v Scargill and others [1984] 3 WLR 501 The defendants were trustees of the Mineworkers’ Pension Scheme, who raised an objection to a new investment plan of trust funds in competing forms of energy. The court decided that the plan would yield the best return for the beneficiaries and refused the application for objection. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘Trustees must do the best they can for the benefit of their beneficiaries, and not merely avoid harming them. I find it impossible to see how it will assist trustees to do the best they can for their beneficiaries by prohibiting a wide range of investments that are authorised by the terms of the trust. Whatever the position today, nobody can say that conditions tomorrow cannot possibly make it advantageous to invest in one of the prohibited investments. It is the duty of trustees, in the interests of their beneficiaries, to take advantage of the full range of investments authorised by the terms of the trust, instead of resolving to narrow that range.’ |

| Megarry VC |

In an action for breach of trust the claimant is required to establish that the trust has suffered a loss which is attributable to the conduct or omission of the trustees. If the trustee’s conduct or omission fell below the required standard imposed on trustees, he becomes personally liable whether he acted in good faith or not.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Lucking’s Will Trust [1968] 1 WLR 866 A trustee-director of a company was liable to the trust when he allowed the managing director and (a friend) to appropriate £15,000 of the company funds through the delivery of blank cheques to the managing director which were signed by the trustee. |

With regard to professional trustees such as banks and insurance companies, the standard of care imposed on such bodies is higher than the degree of diligence expected from a non-professional trustee. The professional trustee is required to administer the trust with such a degree of expertise as would be expected from a specialist in trust administration. This objective standard is applied by the courts after due consideration of the facts of each case.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Bartlett v Barclays Bank [1980] Ch 515 The trust estate was the majority shareholder in a property company and the trustee was a professional trust company. The board of directors, for good commercial reasons, decided to restructure the investment portfolio and invest in land development. The trustee did not actively participate in the company’s deliberations, nor was he provided with regular information concerning the company’s activities, but was content to rely on the annual balance sheet and profit and loss account. One of the schemes pursued by the company proved to be disastrous. In an action brought against the trustee the court held that the trustee was liable because it (the trust corporation) had not acted reasonably in the administration of the trust. |

But while the duties imposed on trustees are onerous, there is no liability for an error of judgment.

JUDGMENT

| ‘A trustee who is honest and reasonably competent is not to be held responsible for a mere error in judgement when the question he has to consider is whether a security of a class authorised, but depreciated in value should be retained or realised, provided he acts with reasonable care, prudence and circumspection.’ |

| Lopes J in Re Chapman [1896] 2 Ch 763 |

In Lloyds TSB Bank plc v Markandan … Uddin (2012), the Court of Appeal affirmed the decision of the trial judge and decided that where the defendants, a firm of solicitors, had acted honestly and conscientiously, but were deceived by a fraudulent third party, the defendants might nevertheless be in breach of trust by failing to act with due care and attention.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Lloyds TSB Bank plc v Markandan … Uddin [2012] EWCA Civ 65, CA The claimant bank was the successor in title to a mortgage lender, namely the Cheltenham and Gloucester Building Society (C…G). C…G offered a mortgage of £742,500 to a person calling himself Mr Victor Davies in order to purchase a residential property. The defendant firm of solicitors, Markandan … Uddin (MU), was instructed to act on behalf of the claimant in respect of the mortgage transaction. Mr Davies also instructed the defendants to act on his behalf in the purchase of the property. In the event, C…G and the defendants were the victims of a fraud. The owners of the property (Gary and Monique Green) had not agreed to sell their property to Victor Davies or to anyone, and were ignorant of the fraud that was carried out. On 24 August 2007 a firm of solicitors called Deen Solicitors (Deen HP), with offices in Holland Park in west London, held themselves out as acting on behalf of the vendors. No such firm existed in Holland Park, although there was a firm called Deen Solicitors in Luton. The Luton firm was not involved in this transaction, and knew nothing of the circumstances of this arrangement. The Holland Park firm fraudulently passed itself off as a branch of the Luton firm. The defendants were sent the building society’s standard form of certificate of title to complete. The certificate of title was completed by the defendants on 29 August 2007. On 31 August the claimant remitted an advance of £742,500 to the defendants. On the same day, Deen HP wrote to the defendants, saying that they had been instructed to pay the purchaser’s legal costs to the defendants. This information ought to have put the defendants on notice as to the suspicious nature of the transaction. Deen HP confirmed that they wished to complete by post and listed the documents to be handed over on completion as the transfer, the certificate of discharge of the current mortgage, the charge certificate and the vendors’ part of the contract. The defendants remitted the sum of £707,613.25 to the account nominated by Deen HP on 4 September. That sum was the advance from the building society less the defendants’ legal fees, costs, stamp duty, land registry fees and disbursements. Although the amount was remitted to Deen HP, no signed contract was obtained from the vendor on that date. On 11 September 2007 the defendants wrote to Deen HP requesting the signed contract, transfer and discharge certificates. On 25 September 2007 Deen HP returned the sum they had received on 4 September, less £5,000, and requested the defendants to send the money back to a different account. On 28 September Deen HP wrote apologising for their conduct in not sending the documents and requesting the funds. On the same day the defendants complied with the request and remitted the funds to Deen HP, despite not having received the documents. Deen HP then disappeared, and the fraud was discovered. The claimant sued for damages for breach of trust. The defendants denied a breach of trust and, in the alternative, claimed relief under s61 of the Trustee Act 1925 and alleged contributory negligence on the part of the claimant. The High Court decided in favour of the claimant and awarded damages against the defendants. The defendants appealed to the Court of Appeal. |

| Held: The Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal and decided that: | |

1. The purported contract of sale was a nullity since the owners had not agreed to sell their property to Mr Victor Davies or anyone else. 2. There was no exchange of money for documents or a solicitor’s undertaking. 3. In the circumstances, the defendants had had no authority to release the loan moneys. Thus, the remission of the moneys to Deen HP was a breach of trust for which the defendants were accountable. 4. Relief under s 61 of the Trustee Act 1925 was dependent on the defendants discharging a burden of proof to show that they acted honestly and reasonably and ought fairly to be excused. In the circumstances, the defendants had failed to discharge this burden in that they had not acted reasonably. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘In this case there was, however, no exchange of money for documents. There was instead a parting of the loan money in exchange for what [the defendants] believed to be the undertakings of Deen, a firm of solicitors. In fact, [the defendants’] belief was wrong and they received no such undertakings … The result was that [the defendants] parted with the loan money in exchange for undertakings that were not of the nature they thought they were. They were themselves direct victims of the fraud and the relevant events of 4 September were in law a nullity … It follows in my view that, as the events of 4 September did not amount to completion, [the defendants] had no authority from C…G to release the loan money to [Deen HP]. They paid it away in breach of trust for which … they were accountable … The careful, conscientious and thorough solicitor, who conducts the transaction by the book and acts honestly and reasonably in relation to it in all respects but still does not discover the fraud, may still be held to have been in breach of trust for innocently parting with the loan money to a fraudster.’ |

| Rimer LJ |

Section 61 of the Trustee Act 1925 may also apply to relieve a trustee from liability (see Chapter 16). This section applies where a trustee has acted honestly and reasonably, and ought fairly to be excused for the breach of trust. In these circumstances the court may relieve him either wholly or partly from personal liability.

14.2.2 Duty and standard of care under the Trustee Act 2000

The Trustee Act 2000 describes the duty of care which is applicable to trustees. Section 1(1) provides that whenever the duty under the subsection applies to a trustee, he must exercise such care and skill as is reasonable in the circumstances, having regard in particular:

(a) to any special knowledge or experience he has or holds himself out as having; and

(b) if he acts as a trustee in the course of a business or profession, to any special knowledge or experience that it is reasonable to expect of a person acting in the course of that kind of business or profession.

Thus, a solicitor who is a trustee will be under a more stringent duty of care and skill, as opposed to a lay trustee.

Schedule 1 of the 2000 Act specifies when the statutory duty of care applies to trustees. These are in the exercise of the statutory and express powers of investment, including the duty to have regard to the standard investment criteria and the duty to obtain and consider proper advice. In addition, the duty applies to the trustees’ power to acquire land. Moreover, the duty of care applies when trustees enter into arrangements in order to delegate functions to agents, nominees and custodians as well as the review of their actions. The duty of care also applies to trustees when exercising their power under s 19 of the Trustee Act 1925 to insure property. However, para 7 of the Schedule enacts that the duty of care does not apply if, or in so far as, it appears from the trust instrument that the duty is not meant to apply. Thus, a settlor may expressly restrict the application of the statutory duty (or the common-law duty of care).

14.3 Duty to act unanimously

Trustees are required to act unanimously, subject to any provision in the trust instrument to the contrary. The settlor has given all of his trustees the responsibility to act on behalf of the trust. Subject to provisions to the contrary in the trust instrument, the acts and decisions of some of the trustees (even a majority of trustees) are not binding on others. Thus, once a trust decision is made, the trustees become jointly and severally liable to the beneficiaries in the event of a breach of trust. In practice, it may be that one trustee is active or dominant, but nevertheless all the trustees must agree on a particular course of action concerning the trust. In Bahin v Hughes (1886) 31 Ch D 390, ‘passive’ trustees were liable to the beneficiaries for breach of trust along with an ‘active’ trustee.

JUDGMENT

| ‘Miss Hughes was the active trustee and Mr Edwards did nothing, and in my opinion it would be laying down a wrong rule to hold that where one trustee acts honestly, though erroneously, the other trustee is to be held entitled to indemnity who by doing nothing neglects his duty more than the acting trustee … In my opinion the money was lost just as much by the default of Mr Edwards as by the innocent though erroneous action of his co-trustee, Miss Hughes. All the trustees were in the wrong, and everyone is equally liable to indemnify the beneficiaries.’ |

| Cotton LJ |

A claim by one trustee against his co-trustee is now subject to the Civil Liability (Contribution) Act 1978. Briefly, a trustee who is sued for breach of trust may claim a contribution from his co-trustee. The court has a discretion to make a contribution order, if such ‘is just and equitable having regard to the extent of the [co-trustee’s] responsibility for the damage in question’.

14.4 Duty to act impartially

In performing their duties, the trustees are required to act honestly, diligently and in the best interests of the beneficiaries. Thus, the trustees are not entitled to show favour to a beneficiary or group of beneficiaries, but are required to act impartially and in the best interests of all the beneficiaries.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Lloyds Bank v Duker [1987] 3 All ER 193 The court refused an application requiring the trustees to transfer to a beneficiary his share of a trust fund, namely 574 shares out of a total of 999 shares (or 46/80 of the trust fund). The transfer would have entitled the beneficiary to a majority holding in the company, which would have exceeded the value of the remaining shares subject to the trust. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘I can … get some help from another general principle. I mean the principle that trustees are bound to hold an even hand among their beneficiaries, and not favour one as against another, stated for instance in Snell’s Principles of Equity, op cit, p. 225. Of course Mr Duker must have a larger part than the other beneficiaries. But if he takes 46/80ths of the shares he will be favoured beyond what Mr Smith intended, because his shares will each be worth more than the others. The trustees’ duty to hold an even hand seems to indicate that they should sell all 999 shares instead.’ |

| Mowbray QC |

The duty on the trustees to act impartially or with even-handedness is of paramount importance with regard to the exercise of the trustees’ discretion. The claimant will undoubtedly bear the legal burden to prove that the trustee has acted in breach of his duty of impartiality, but it is not an easy task to challenge the exercise by a trustee of a discretion. One basis on which the trustee’s decision might be challenged would be to establish that it was perverse, in the sense that no reasonable trustee could properly have taken it. Another would be to show that the trustee had proceeded on the basis of some mistake of fact or law which vitiates the decision. That is the principle often referred to as the rule in Re Hastings Bass [1975] Ch 25. It was established that in the case of a discretion which the trustee is not under a duty to exercise, a party seeking to challenge the trustee’s decision has to show that the trustee would (and not merely might) have taken a different decision had he not made the mistake (see Sieff v Fox [2005] 1 WLR 3811 and Betafence v Veys [2006] EWHC 999 (Ch)). But in Pitt v Holt; Futter v Futter [2013] 2 AC 108 (see earlier), in a conjoined appeal, the Supreme Court decided that to lay down a rigid rule of proving that the trustees either ‘would not’ or ‘might not’ have made a different decision, would inhibit the court in seeking the best practical solution in the application of the Hastings-Bass rule in a variety of different factual situations. As a matter of principle there must be a high degree of flexibility in the range of the court’s possible responses. A third basis would be to show that the trustee exercised his discretion to achieve an unlawful purpose, that is to say, a purpose other than that for which the power was given. In Chirkinian v Arnfield [2006] EWHC 1917 (Ch), the court decided that although a beneficial unsecured loan potentially puts the assets of the trust in jeopardy, the risks are taken for the benefit of the beneficiary. Such a loan should not be recalled unless the trustee considered it to be in the interests of the debtor beneficiary, or other beneficiaries to do so. The judge ruled that, on the facts of this case, a decision to call in a beneficial loan and pursue the beneficiary debtor to the point of bankruptcy could not be treated as an instance of the trustee acting neutrally. From the evidence no consideration was given to the interests of the beneficiary and the judgment of the trustee was seriously flawed. In reality the trustee appeared to prefer the interests of the liquidator as opposed to the interests of the beneficiary.

The effect of this even-handedness rule is that the trustees are required to take positive steps to avoid placing themselves in a position where their duties may conflict with their personal interests. If there is a conflict of the trustees’ duties and interest, the trustees are required to hand over any unauthorised benefit to the beneficiaries. Thus, it is imperative that the trustees do not deviate from the terms of the trust without the authority of the beneficiaries or the court.

An additional feature of the duty imposed on the trustees to act impartially is to ensure that the trust property is properly balanced to accomodate the interests of present and future beneficiaries. Thus, the trustees are obliged to ensure that the trust property produces both a reasonable income for the benefit of those beneficiaries entitled to income, such as the life tenant, and to create capital growth for beneficiaries entitled to capital, such as the remainderman. Where the trust assets are likely to deteriorate, such as machinery, and the assets are held on trust for A for life with remainder to B absolutely, the trustees may be in breach of the duties to the remainderman if they do not consider re-investing the trust property.

A duty to convert trust assets may arise from the express terms of the trust instrument, by statute or by rules of equity. Under s 3 of the Trusts of Land and Appointment of Trustees Act 1996, the doctrine of conversion has been abolished in respect of a trust of land. In short, where land is held by trustees subject to a trust for sale, the land is not treated in equity as personal property.

Prior to the Trusts (Capital and Income) Act 2013, the equitable rules of apportionment were created by the rule in Howe v Earl of Dartmouth (1802) 7 Ves 137, the rule in Re Earl of Chesterfield’s Trusts (1833) 24 Ch D 643, the rule in Allhusen v Whittell (1867) LR 4 EQ 295 and s 2 of the Apportionment Act 1870. The first branch of the rule in Howe v Earl of Dartmouth created an implied trust for sale in respect of a residuary personal estate held on trust for beneficiaries in succession that are of a wasting, hazardous and unauthorised character. The second branch of this rule compensated the capital beneficiary for loss pending the conversion of the trust assets. The rule in Re Earl of Chesterfield’s Trusts is to the effect that where the trust property, created by will, included a non-income producing asset, such as a reversion or a life policy, the proceeds of the non-income producing asset are apportioned between the life tenant and the remainderman. The remainderman will receive a sum which, if invested at compound interest at the date of death at 4 per cent per annum (less income tax), would produce the proceeds of sale. The balance is paid over to the life tenant. The rule in Allhusen v Whittell apportions debts, liabilities, legacies and other charges payable out of the residuary estate between capital and income beneficiaries. The effect of the rule is to charge the life tenant with interest on the sums used to pay debts and other liabilities in order to maintain equality between the beneficiaries. Section 2 of the Apportionment Act 1870 created a rule of time apportionment. The effect of the section is that income beneficiaries are entitled only to the proportion of income that is deemed to have accrued during their period of entitlement. The nature of these rules was summarised by the Law Commission in its Report, ‘Capital and income in trusts: classification and apportionment’ in 2009, thus:

QUOTATION

| ‘These rules are all based on the principle that no beneficiary should take a disproportionate benefit at the expense of another. They are logical developments of the classification rules and of the duty to balance the interests of beneficiaries interested in capital and income. The difficulty is that they were formulated many decades ago and in circumstances much less likely to arise today. They are prescriptive, unclear in places and generally require complicated calculations relating to disproportionately small sums of money. Well drafted trust instruments exclude these rules. In most trusts where they have not been excluded (particularly those that arise by implication) they are either ignored or cause considerable inconvenience.’ |

The Law Commission concluded that the rules of apportionment were archaic and inconvenient and recommended their abolition for future trusts, subject to any contrary intention in the trust instrument. These recommendations were adopted by Parliament in enacting the Trusts (Capital and Income) Act 2013.

Section 1 of the Trusts (Capital and Income) Act 2013 provides:

SECTION

’1 Disapplication of apportionment etc rules (1) Any entitlement to income under a new trust is to income as it arises (and accordingly section 2 of the Aportionment Act 1870, which provides for income to accrue from day to day, does not apply in relation to the trust). (2) The following do not apply in relation to a new trust– (a) the first part of the rule known as the rule in Howe v Earl of Dartmouth (which requires certain residuary personal estates to be sold); (b) the second part of that rule (which withholds from a life tenant income arising from certain investments and compensates the life tenant with payments of interest); (c) the rule known as the rule in Re Earl of Chesterfield’s Trusts (which requires the proceeds of the conversion of certain investments to be apportioned between capital and income); (d) the rule known as the rule in Allhusen v Whittell (which requires a contribution to be made from income for the purpose of paying a deceased person’s debts, legacies and annuities). (3) Trustees have power to sell any property which (but for subsection (2)(a) they would have been under a duty to sell. (4) Subsections (1) to (3) have effect subject to any contrary intention that appears – (a) in any trust instrument of the trust, and (b) in any power under which the trust is created or arises. (5) In this section ‘new trust’ means a trust created or arising on or after the day on which this section comes into force.’ The effect of s 1 of the Trusts (Capital and Income) Act 2013, is that in respect of future trusts (‘new trusts’), namely trusts created on or after 1 October 2013 (the appointed date), the archaic and complex apportionment rules will not be implied in to trust instruments. The apportionment rules are required to be expressly incorporated in the trust instrument if they are to operate. Instead, the possible sale and reinvestment of trust property will become part of the trustees’ general duties of investment under the Trustee Act 2000. |

14.5 Duty to act personally

Generally speaking, a trustee is appointed by a settlor because of his personal qualities. It is expected that the trustee will act personally in the execution of his duties. The general rule is delegatus non potest delegare.

delegatus non potest delegare

A delegate cannot delegate his duties.

However, in the contemporary commercial climate the functions and needs for the proper administration of a trust have become increasingly complex, requiring specialised skill and knowledge. Accordingly, it is unrealistic to expect trustees to act personally in all matters relating to the trust. Trustees are entitled to appoint agents to perform acts in respect of the trust.

Part IV of the Trustee Act 2000 has reformed the law as to the trustees’ powers of delegation. It repeals ss 23 and 30 of the Trustee Act 1925 (which created some confusion regarding the duties of trustees) and introduces provisions with a clearer framework for delegation. Generally, the new provisions deal with the appointment of agents, nominees and custodians and the liability of the trustees for such persons.

Sections 11–20 of the Trustee Act 2000 deal with the appointment of agents, nominees and custodians. Sections 21–23 deal with the review of acts of the agents, nominees and custodians and the question of liability for their acts.

Section 11(1) enacts that the trustees of a trust ‘may authorise any person to exercise any or all of their delegable functions as their agent’. Section 11(2) defines ‘delegable functions’ as any function of the trustee, subject to four exceptions. These are:

(a) functions relating to the distribution of assets in favour of beneficiaries, i.e. dispositive functions;

(b) any power to allocate fees and other payments to capital or income;

(c) any power to appoint trustees; and

(d) any power conferred by the trust instrument or any enactment which allows trustees to delegate their administrative functions to another person.

Thus, the trustees cannot delegate their discretion under a discretionary trust to distribute the funds or to select beneficiaries from a group of objects. But they may delegate their investment decision-making power and thereby obtain skilled professional advice from an investment manager.

In the case of charitable trusts, the trustees’ delegable functions are set out in s 11(3) as follows:

SECTION

’(a) ‘any function consisting of carrying out a decision that the trustees have taken; (b) any function concerning investment of assets subject to the trust; (c) any function relating to the raising of funds for the trust otherwise than by means of profits of a trade which is an integral part of carrying out the trust’s charitable purpose; (d) any other function prescribed by order of the Secretary of State. ’ |

Section 12 provides who may or may not be appointed an agent of the trustees. The trustees may appoint one of their number to act as an agent, but cannot appoint a beneficiary to carry out that function. If more than one person is appointed to exercise the same function, they are required to act jointly.

Section 14 authorises the trustees to appoint agents on such terms as to remuneration and other matters as they may determine. But certain terms of the agency contract are subject to a test of reasonableness. These are terms permitting the agent to sub-delegate to another agent, or to restrict his liability to the trustees or the beneficiaries, or to allow the agent to carry out functions that are capable of giving rise to a conflict of interest. Thus, sub-delegation to another trustee or the insertion of an exclusion clause in the contract appointing the agent is subject to a test of reasonableness.

Section 15 imposes special restrictions within certain types of agency contracts. With regard to asset-management functions the agreement is required to be evidenced in writing. In addition, the trustees are required to include a ‘policy statement’ in the agreement, giving the agent guidance as to how the functions ought to be exercised, and should seek an undertaking from the agent that he will secure compliance with the policy statement. In the ordinary course of events, the policy statement will refer to the ‘standard investment criteria’ and, in the case of beneficiaries entitled in succession, require the agent to provide investments with a balance between income and capital.

Section 24 provides that a failure to observe these limits does not invalidate the authorisation or appointment.

14.5.1 Power to appoint nominees

Section 16 of the Act of 2000 authorises trustees to appoint nominees in relation to such of the trust assets as they may determine (other than settled land). In addition, the trustees may take steps to ensure the vesting of those assets in the nominee. Such appointment is required to be evidenced in writing.

14.5.2 Power to appoint custodians

Section 17 of the Trustee Act 2000 authorises the trustees to appoint a person to act as custodian in relation to specified assets. A custodian is a person who undertakes the safe custody of the assets or any documents or records concerning the assets. The appointment is required to be evidenced in writing.

14.5.3 Persons who may be appointed as nominees or custodians

Section 19 of the Trustee Act 2000 provides that a person may not be appointed as a nominee or custodian unless he carries on a business which consists of or includes acting as a nominee or custodian, or is a body corporate controlled by the trustees. The trustees may appoint as a nominee or custodian one of their number if that is a trust corporation, or two (or more) of their number if they act jointly.

14.5.4 Review of acts of agents, nominees and custodians

Provided that the agent, nominee or custodian continues to act for the trust, the trustees are required to:

■ keep under review the arrangements under which they act, and how those arrangements are put into effect;

■ consider whether to exercise any powers of intervention, if the circumstances are appropriate;

■ intervene if they consider that a need has arisen for such action.

14.5.5 Liability for the acts of agents, nominees and custodians

Section 23 of the Trustee Act 2000 provides that a trustee will not be liable for the acts of agents, nominees and custodians provided that he complies with the general duty of care laid down in s 1 and Sched 1, both in respect of the initial appointment of the agent etc., and when carrying out his duties under s 22 (review of acts of agents etc.). The effect of this provision is that it lays to rest the eccentric principles that were applied under the 1925 Act, and introduces one standard objective test concerning the trustees’ duty of care.

14.6 Other statutory provisions permitting delegation of discretions

Trustees may delegate their discretions under the following statutory provisions:

■ Part IV of the Trustee Act 2000 (see above);

■ s 25 of the Trustee Act 1925 (as amended by the Trustee Delegation Act 1999); or

■ s 9 of the Trusts of Land and Appointment of Trustees Act 1996 (see below).

Individual delegation

Section 25 of the Trustee Act 1925 (as re-enacted by s 5 of the Trustee Delegation Act 1999) enables a trustee to delegate, by a power of attorney, ‘the execution or exercise of all or any of the trusts, powers and discretions vested in him either alone or jointly with any other person or persons’. The delegation of the powers commences on the date of execution or such time as stated in the instrument, and continues for a period of 12 months or such shorter period as mentioned in the instrument. Written notice is required to be given by the donor of the power to each nominee under the trust instrument who is entitled to appoint trustees, and each other trustee within seven days after its creation. The donor of the power remains liable for the acts or defaults of the donee.

14.6.1 Delegation under the Trusts of Land and Appointment of Trustees Act 1996

Section 9 of the 1996 Act enacts that trustees of land may delegate any of their powers in relation to the land by a power of attorney to adult beneficiaries who are currently entitled to interests in possession. In exercising their powers, the trustees are required to have regard to the rights of the beneficiaries and are obliged to observe any rules of law and equity. Thus, the trustees may not favour or prejudice the interest of any beneficiary when exercising their powers. It should be noted that the powers included in s 6 relate only to a trust of land and not to any personal property. In addition, the s 6 powers may be amended or excluded by the settlement, or made subject to obtaining the consent of any person (s 8). Thus, the settlor may prevent any dealing with the land (although this could be challenged under s 14: see above). In the case of charitable trusts, the trustees’ powers may not be amended or excluded, but they may be made subject to obtaining consent.

Protection of purchasers from delegate

In respect of land, where a person deals with the delegate in good faith in the belief that the trustees were entitled to delegate to that person, it is presumed that the trustees were entitled to delegate to that person, unless the purchaser had knowledge at the time of the transaction that the trustees were not entitled to delegate to that person (s 9(2)). ‘Knowledge’ for these purposes has not been defined in the legislation, but it is submitted that since we are concerned here with a proprietary interest, any type of cognisance will suffice for these purposes, even constructive knowledge.

14.7 Exclusion clauses

Exclusion clauses which are validly inserted in trust instruments may have the effect of limiting the liability of trustees. Such clauses are not, without more, void on public policy grounds. Of course, in order for the trustee to secure protection from claims for breach of trust, the exclusion clause is required to exempt or exclude liability for the particular fault which is the subject-matter of the complaint. Moreover, provided that the clause does not purport to exclude the basic minimum duties ordinarily imposed on trustees, it may be valid. Some of the minimum duties which cannot be excluded are the duties of honesty, good faith and acting for the benefit of the beneficiaries: see Armitage v Nurse [1997] 3 WLR 1046. In this case, Millett LJ made the following observations:

JUDGMENT

| ‘I accept the submission … that there is an irreducible core of obligations owed by the trustees to the beneficiaries and enforceable by them which is fundamental to the concept of a trust. If the beneficiaries have no rights enforceable against the trustees there are no trusts. But I do not accept the further submission that these core obligations include the duties of skill and care, prudence and diligence. The duty of the trustees to perform the trusts honestly and in good faith for the benefit of the beneficiaries is the minimum necessary to give substance to the trusts, but in my opinion it is sufficient. It is, of course, far too late to suggest that the exclusion in a contract of liability for ordinary negligence or want of care is contrary to public policy. What is true of a contract must be equally true of a settlement.’ |

In Armitage, the claimant, under an accumulation and maintenance settlement, sued the trustees for breach of trust. The trust settlement contained an exclusion clause to the effect that the trustees were not liable to the trust for any loss or damage to the income or capital, ‘unless such loss or damage shall be caused by their own actual fraud’. The court decided that the clause validly protected the trustees from liability. ‘Actual fraud’ involved an intention on the part of the trustee to pursue a course of action, either knowing that it is contrary to the interests of the beneficiaries or being recklessly indifferent whether it is contrary to their interests or not. The trustees were not guilty of actual fraud and could enlist the protection of the exemption clause.

tutor tip

‘Note the distinction between the trustees’ fiduciary and non-fiduciary duties.’

In Armitage, liability for negligence may be excluded, even liability for gross negligence. But Millett LJ declared that the trustees’ duty to act ‘honestly and in good faith for the benefit of the beneficiaries is the minimum necessary to give substance to the trust’. The question arises as to how far an exclusion clause may protect the trustees from liability for breach of trust. It is clear that dishonest conduct on the part of the trustees that causes a breach of trust will not protect them from liability for breach of trust. What is meant by ‘dishonesty’? In Chapter 9 we considered the Royal Brunei test for dishonesty. In the context of exclusion clauses, it is arguable that a different test is envisaged, namely the subjective test. In Armitage, Millett LJ said that dishonesty requires ‘at the minimum an intention on the part of the trustee to pursue a particular course of action, either knowing that it is contrary to the interests of the beneficiaries or being recklessly indifferent whether it is contrary to their interests or not’. This appears to be a subjective approach based on the defendant’s knowledge of the circumstances. On the other hand, in Walker v Stones [2001] QB 902], the Court of Appeal was asked to determine whether a solicitor was dishonest if he did not subjectively appreciate that he was being dishonest because he believed that he was acting in the best interests of the beneficiaries. The court decided that there was sufficient evidence of dishonesty because no reasonable solicitor acting as a trustee would have considered it to be honest to act in this way. This is an objective test. Would recklessness on the part of the trustees entitle them to protection? In Barraclough v Mell [2005] EWHC B17 (Ch), an exclusion clause was inserted into a will trust. The trustee made unauthorised payments from the trust fund but was unaware of the wrongfulness of his actions. But when this was brought to his attention he immediately set out to recover the funds. The court decided that he was entitled to rely on the exclusion clause. The approach here was to consider the recklessness of the trustee as not equivalent to dishonesty.

The burden of proof lies on the party seeking to rely on the exclusion clause to establish that the clause was properly inserted into the trust instrument and it covers the breach that has taken place. Much depends on the wording of such clauses. The words used in the exclusion will be given their natural meaning. Prima facie any ambiguities are construed against the trustees.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Wight v Olswang, The Times, 18 May 1999 A trust settlement incorporated two conflicting exemption clauses, one protecting all trustees from liability for breach of trust (a general exemption clause) and the other which applied only to unpaid trustees. The court decided that the paid trustees could not rely on the general exemption clause. |

In substance, it would appear that there are two types of exclusion clause:

(a) a clause which excludes the trustees’ liability for breach of trust; and

(b) a clause which not only excludes the trustees’ liability, but also excludes the duties,

or some of the duties, of the trustees from a claim for a breach of trust. In respect of the first type of clause, Millett LJ in Armitage v Nurse (above) took the view that the trustees may only exclude their liability for negligence, but they remain liable for dishonest breaches of trust. Regarding the second type of clause, Millett LJ in the same case expressed his opinion that the ‘core duties’ of trustees cannot be effectively excluded for this may lead to repugnancy with the trust. He stated, ‘the duty of the trustees to perform the trusts honestly and in good faith for the benefit of the beneficiaries is the minimum necessary to give substance to the trusts’.

The difficulties in pursuing a claim for breach of trust in seeking to restrict an exclusion clause in the trust deed by reference to the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 (UCTA 1977) (included in Tuckey LJ’s judgment below) were considered by the Court of Appeal in Baker v JE Clark … Co [2006] All ER (D) 337 (Mar). The court decided that the notice requirement under the 1977 Act was impractical and the clause did not exclude liability under a ‘contract’.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Baker v JE Clark … Co [2006] All ER (D) 337 (Mar) The claimant was the wife of the deceased who was employed by the defendant company. The company sponsored a personal pension plan which included provision for death-in-service benefits. The rules of the scheme were set out in a supplementary trust deed containing an exemption clause excluding liability unless there was bad faith. The deceased joined the scheme but subsequently the underwriters of the scheme refused to renew coverage under the scheme. The deceased later passed away from a brain tumour in the service of the company and no death benefits were payable. The claimant brought an action against the administrator of the scheme alleging breach of his duty of care at common law or equity and under UCTA 1977 was not entitled to rely on the exclusion clause in the trust deed. The court decided that there was no requirement of notice of the exemption clause to be given in advance. Indeed, such a requirement would be impractical. Trustees undertook unilateral obligations and their terms of service were not dependent on the consent of the beneficiary. Further, there were insuperable difficulties in applying UCTA 1977 to trustee exemption clauses. Such clauses did not necessarily arise under contracts with the trustees because trust deeds were not contracts. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘It seems to me that there are insuperable difficulties in seeking to apply the 1977 Act to an exemption clause of the kind with which this case is concerned. Assuming that there is a common-law duty of care, the question is whether CI 13.3 (of the scheme) is a notice of the kind referred to in s 2. I do not think it is. This point was considered by the Law Commission in their consultation paper 171 published in 2003 on the subject of trustee exemption clauses. After having concluded that a trustee exemption clause is not a contract they say at para 2.62: |

| While there may be a stronger argument that a trustee exemption clause is a form of ‘notice’, this may also be somewhat speculative in that it would seem that ‘notice’ within the 1977 Act is primarily intended to cover attempts to exclude liability by reference to a sign outside the confines of a formal legal document. ‘ | |

| Tuckey LJ |

Law Commission proposals

On 19 July 2006 the Law Commission published its report on ‘Trustee exemption clauses’ and listed a number of recommendations. Prior to this, a consultation paper on ‘Trustee exemption clauses’, published in 2003, identified a number of responses. Some of these are:

1. There was a general distaste for wide exclusion clauses especially where the settler is unaware of their existence or meaning.

2. A distinction ought to be drawn between professional and lay trustees but it was recognised that this may be difficult to apply and liable to cause unfairness (especially in relation to professionals acting pro bono).

3. The practicality of the proposal that all trustees should have the power to purchase indemnity insurance using trust funds was questioned on the grounds of cost and availability.

4. There was widespread concern about the likely adverse impact of statutory regulation restricting reliance on trustee exemption clauses. This may result in increased indemnity insurance premiums and the possible unavailability of insurance, a decrease in the flexibility of the management of trust property and the increase in speculative litigation for breach of trust and a possible reluctance to accept trusteeship.

The 2006 Report recommends that the trust industry adopt a non-statutory rule of practice and this should be enforced by the regulatory and professional bodies which govern trustees and drafters of trusts. The rule will be enforced by professional bodies who may discipline its members who fail to comply. The recommended rule of practice requires paid trustees and drafters of trust instruments to take reasonable steps to ensure that settlors understand the meaning and effect of exemption clauses to be included in trusts instruments, before the creation of such trusts. This rule will not apply to pension trusts or trusts already subject to statutory regulation.

14.8 Duty to provide accounts and information

Because of the nature of the fiduciary relationship of trustees, a duty is imposed on them to keep proper accounts for the trust. In pursuance of this objective, the trustees may employ an agent (an accountant) to draw up the trust accounts. The beneficiaries are entitled to inspect the accounts but if they need copies they are required to pay for these from their own resources.

In O’Rourke v Darbishire [1920] AC 581, Lord Wrenbury declared that the beneficiary’s right to disclosure of trust documents is proprietary because they belong to him. He also drew a distinction between disclosure and discoveries:

JUDGMENT

| The beneficiary is entitled to see all trust documents because they are trust documents and because he is a beneficiary. They are in this sense his own. Action or no action, he is entitled to access to them. This has nothing to do with discovery. The right to discovery is a right to see someone else’s documents. The proprietary right is a right to access to documents which are your own.’ |

In Re Londonderry’s Settlement [1964] 3 All ER 855, Salmon LJ adopted the principle laid down by Lord Wrenbury and decided that the beneficiaries are entitled to inspect documents created in the course of the administration of the trust. These are trust documents and are prima facie the property of the beneficiaries. Indeed, ‘trust documents’ were described by Salmon LJ in Re Marquess of Londonderry’s Settlement [1965] Ch 918 as possessing the following characteristics:

JUDGMENT

| ’(i) ‘they are documents in the possession of the trustees as trustees; (ii) they contain information about the trust, which the beneficiaries are entitled to know; (iii) the beneficiaries have a proprietary interest in the documents, and, accordingly, are entitled to see them.’ |

However, in Schmidt v Rosewood Trust Ltd [2003] 3 All ER 76, the Privy Council rejected the statement of the principle in O’Rourke v Darbishire (1920), and decided that the more principled approach to the issue is to regard the right to seek disclosure of trust documents as one aspect of the court’s inherent jurisdiction to supervise, and if necessary to intervene in, the administration of trusts. Accordingly, the beneficiary’s right to inspect trust documents is founded not on an equitable proprietary right in respect of those documents, but upon the trustee’s fiduciary duty to inform the beneficiary and to render accounts. This right to seek the court’s intervention is not restricted to beneficiaries with fixed interests in the trust, but also extends to objects under a discretionary trust. The power to seek disclosure may be restricted by the court in the exercise of its discretion. The court is required to balance the competing interests of the different beneficiaries, the trustees and third parties.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Schmidt v Rosewood Trust Ltd [2003] 3 All ER 76 The settlor executed two Isle of Man trust settlements which created a discretionary trust in favour of a group of objects, including the claimant. The defendant company became the sole trustee of the two settlements. The settlor died intestate. The claimant alleged that he devoted considerable time and resources to trace his father’s assets and believed that his efforts had been frustrated by some of his father’s co-directors. He applied in his personal capacity as a member of a class of objects, and as administrator for disclosure of trust accounts and information about the trust assets. The defendant contended that a beneficiary’s right of disclosure of trust documents is treated as a proprietary right, and that an object of a discretionary power does not have such a right, but merely a hope of acquiring a benefit. The Isle of Man court held in favour of the defendant and the claimant appealed to the Privy Council. The Court allowed the appeal and decided that: |

(a) The right to seek the court’s intervention does not depend on entitlement to an interest under the trust. An object of a discretionary trust (including a mere power of appointment) may also be entitled to protection from a court, although the circumstances concerning protection and the nature of the protection would depend on the court’s discretion. (b) No beneficiary has an entitlement, as of right, to disclosure of trust documents. Where there are issues of personal and commercial confidentiality, the court will have to balance the competing interests of the beneficiaries, the trustees and third parties and limitations or safeguards may be imposed. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘[T]he more principled and correct approach is to regard the right to seek disclosure of trust documents as one aspect of the court’s inherent jurisdiction to supervise, and if necessary to intervene in, the administration of trusts. The right to seek the court’s intervention does not depend on entitlement to a fixed and transmissible beneficial interest.’ |

| Lord Walker |

14.9 Duty to distribute to the correct beneficiaries

It is an elementary principle of trusts law that the trustees are required to distribute the trust property (income and/or capital) to the beneficiaries properly entitled to receive the same. Failure to distribute to the correct beneficiary subjects the trustees to liability for breach of trust, although in appropriate cases they may apply to the court for relief under s 61 of the Trustee Act 1925 (see Chapter 16). Thus, in Eaves v Hickson (1861) 30 Beav 136, trustees were liable to make good sums wrongly paid to a beneficiary in reliance on a forged marriage certificate. Likewise, in Re Hulkes (1886) 33 Ch D 552, the trustees were liable for sums paid to the wrong beneficiaries based on an honest, but incorrect, construction of the trust instrument.

Where the trustee makes an overpayment of income or instalment of capital, he may recover the amount of the overpayment by adjusting the payments subsequently made to the same beneficiary. Where the payment is made to a person who is not entitled to receive the sum, the trustee has the right to recover the amount based on a quasi-contractual claim of money paid under a mistake of fact. Such claim will not succeed if the mistake is one of law. This was illustrated in Re Diplock [1947] Ch 716 (see below).

CASE EXAMPLE

| Woolwich Building Society v IRC (No 2) [1992] 3 All ER 737 The House of Lords decided that money paid by a member of the public to a public authority in the form of taxes paid, pursuant to an ultra vires demand by the authority, is prima facie recoverable by the member of the public as of right. An aggrieved beneficiary may, in addition to his right to sue the trustee, trace his property in the hands of the wrongly paid person. |

Where the trustees have a reasonable doubt as to the validity of claims of the beneficiaries, they may apply to the court for directions, and will be protected, provided that they act in accordance with those directions. The court has the power to make a Benjamin order (derived from the case Re Benjamin [1902] 1 Ch 723), authorising the distribution of the trust property without identifying all the beneficiaries and creditors.

In addition, where the trustees cannot identify all the beneficiaries, they are entitled to pay the trust funds into court as a last resort: see Re Gillingham Bus Disaster Fund [1959] Ch 62. Where there is no good reason for a payment into court, the trustees may personally have to pay the costs of such an application.

By virtue of s 27 of the Trustee Act 1925, a simplified form of distribution is allowed and, at the same time, the trustees or personal representatives are given protection from claims for breach of trust. The section permits the trustees (or personal representatives) to advertise for beneficiaries in an appropriate newspaper or gazette, and after the expiration of a period of time, not being less than two months, they are entitled to distribute the property to the beneficiaries of whom the trustees are aware. If the trustees comply with the requirements of s 27, they will not be liable for breach of trust at the instance of beneficiaries, of whom the trustees were unaware. However, the ignored beneficiaries are entitled to trace their property in the hands of the recipient. Finally, the section is incapable of being excluded or modified by the trust instrument.

14.10 Duty not to make profits from the trust

This duty was dealt with earlier, in Chapter 8 to which reference ought to be made. A trustee is undoubtedly a fiduciary and accordingly his position attracts a number of fiduciary duties. The justification for this rule is the notion that the trustee has control over the trust property which he is required to use solely for the benefit of the beneficiaries. In addition, the confidential nature of the relationship imposes on the trustee an overriding duty of loyalty to the beneficiaries. It was stated earlier that a fiduciary is one whose judgment and confidence is relied on by the beneficiaries or the principal. In Bristol and West Building Society v Mothew [1996] 4 All ER 698, Millett LJ outlined the nature of the fiduciary relationship as follows:

JUDGMENT

| ‘A fiduciary is someone who has undertaken to act for or on behalf of another in a particular matter in circumstances which give rise to a relationship of trust and confidence. The distinguishing obligation of a fiduciary is the obligation of loyalty. The principal is entitled to the single-minded loyalty of his fiduciary. This core liability has several facets. A fiduciary must act in good faith; he must not make a profit of his trust; he must not place himself in a position where his duty and interest may conflict; he may not act for his own benefit or the benefit of a third person without the informed consent of his principal. This is not intended to be an exhaustive list but it is sufficient to indicate the nature of fiduciary obligations. They are defining characteristics of the fiduciary.’ |

The primary duty is to act in the best interests of the beneficiaries and not to allow his interest to conflict with his duties. The effect is that, in equity, there are two overlapping duties imposed on the fiduciary namely, the trustee is not allowed to make a profit from his fiduciary position (referred to as the ‘no profit’ rule) and a fiduciary may not be allowed to place himself in a position of conflict of duty and personal interest (referred to as the ‘no conflict’ rule). It is arguable that the first principle is part and parcel of the second rule. The better view, however, is that although the principles overlap they are distinct principles. The rationale for the harsh rule in Keech v Sandford (1726) 2 Eq Cas Abr 7419 was stated by Lord Herschell in Bray v Ford [1896] AC 44, as not based on principles of morality but as a deterrent to curb the excesses of human nature. Accordingly the ‘no conflict’ ‘no profit’ rule will be strenuously pursued by the courts.

JUDGMENT

| ‘It is an inflexible rule of a court of equity that a person in a fiduciary position … is not, unless otherwise expressly provided, entitled to make a profit; he is not allowed to put himself in a position where his interest and his duty conflict. It does not appear to me that this rule is … founded upon principles of morality. I regard it rather as based on the consideration that human nature being what it is, there is a danger, in such circumstances, of the person holding a fiduciary interest being swayed by interest rather than duty, and thus prejudicing those he is bound to protect. It has, therefore, been deemed expedient to lay down this positive rule.’ |

| Lord Herschell |

The principles are of wide application, strictly adhered to, and it is irrelevant that the beneficiaries suffer no loss and that the trustee acts in good faith. The duty is sometimes referred to as the rule in Keech v Sandford (see Chapter 8). The court decided that the trustee held the renewed lease on trust for the infant beneficiary. The obligation attaches to any property added to the trust: see Boardman v Phipps [1967] 2 AC 46 (see Chapter 8), and also the interests of the beneficiaries. In the latter case, the purchase is voidable at the instance of the beneficiary, even if the market price was paid for the property.

14.10.1 The rule against self-dealing

A trustee, without specific authority to the contrary, is not entitled to purchase trust property for his own benefit: see Keech v Sandford, above. The position remains the same even if the purchase appears to be fair. Perhaps the purchase price might significantly exceed the market value of the property. In such a case, the transaction is treated as voidable, i.e. valid until avoided. In Tito v Waddell (No 2) [1977] Ch 106, Megarry VC said that ‘if a trustee purchases trust property from himself, any beneficiary may have the sale set aside … however fair the transaction’. This is the rule against self-dealing and involves a conflict of duty and interest. The objections to such transactions were laid down in Ex parte Lacey (1802) 6 Ves 265 and Ex parte James (1803) 8 Ves 337. They are that the trustee would be both vendor and purchaser and it would be difficult to ascertain whether an unfair advantage had been obtained by the trustee. In addition, the property may become virtually unmarketable since the title may indicate that the property was at one time trust property. Third parties may have notice of this fact and any disputes concerning the trust property may affect their interest.

The courts will consider all the circumstances to determine whether there is any attempt to avoid this strict rule. Thus, in Wright v Morgan [1926] AC 788, the trustee retired from the trust in order to purchase the trust property at a price which was fixed by an independent valuer. The Privy Council decided that there was a conflict of duty and interest and the sale was set aside at the instance of the beneficiaries. Equally, the rule extends to purchases by the spouses of trustees and to purchases by companies in which the trustee has an interest. The rule will also apply to a sale to a third party if there is an understanding that the trustee will then purchase the property.

In exceptional circumstances the rule may be relaxed, but these are occasions which are peculiar to the facts of each case. In Holder v Holder [1968] Ch 353, an executor purchased a farm which was part of the deceased estate at a fair price at an auction. The Court of Appeal refused to set aside the sale on the grounds that he performed minimal duties as executor before renouncing his duties long before the sale, he made no secret of his intention to purchase the farm, the beneficiaries entitled to share in the estate did not rely on the purchaser’s confidence and judgment to protect their interests and in any event they had acquiesced in the purchase.

There are various exceptions to this rule. The burden of proof is on the trustee/purchaser to establish clearly that there was no hint of impropriety on the part of the trustee after full disclosure was made to the beneficiaries. The following occasions exist when authority may be obtained to purchase the trust property. First, the settlement or will may expressly permit a trustee to purchase the trust property. Second, if all the beneficiaries are of full age and sound mind and absolutely entitled to the property they may agree to the sale. The underlying issues here would be whether the trustees had made full disclosure of all the material facts to the beneficiaries and whether the beneficiaries were capable of exercising an independent judgment. In this event, the beneficiaries may need separate legal advice.

14.10.2 The fair-dealing rule

The fair-dealing rule is applicable where the trustee purchases the beneficial interests of his beneficiaries. It is less stringent than the self-dealing rule. In a sense the trustee is not both vendor and purchaser. The issue here is whether the trustee can discharge the onus of proving that he has made full disclosure of the material facts to the beneficiary, and that the beneficiary exercised an independent judgment when selling his interest to the trustee. The duty of disclosure is required to be of such a degree that the beneficiary is able to exercise an independent judgment as to the nature and extent of the sale. If this burden is discharged so that the transaction is at arm’s length the sale may not be set aside. In Coles v Trescothick (1804) 9 Ves 234, Lord Eldon explained the rule in the following manner:

JUDGMENT

| ‘A trustee may buy from the cestui que trust, provided there is a distinct and clear contract, ascertained to be such after a jealous and scrupulous examination of all the circumstances, proving that the cestui que trust intended the trustee should buy; and there is no fraud, no concealment, no advantage taken, by the trustee of information, acquired by him in the character of trustee.’ |

In Tito v Waddell (No 2) [1977] Ch 106, Megarry VC summarised the rule in the following manner:

JUDGMENT

| The fair dealing rule is that if a trustee purchases the beneficial interest of any of his beneficiaries, the transaction is not voidable ex debito justitiae, but can be set aside by the beneficiary unless the trustee can show that he has taken no advantage of his position and has made full disclosure to the beneficiary, and that the transaction is fair and honest.’ |

Whether the trustee can discharge the burden cast on him is a question of fact. The courts will scrupulously examine the facts to determine whether there has been an unfair advantage acquired by the trustee. In Dougan v Macpherson [1902] AC 197, a purchase of a beneficial interest by a trustee/beneficiary was set aside by the House of Lords after it transpired that the purchaser/trustee had withheld information from the beneficiary that affected the value of the property.

14.10.3 Remuneration and other financial benefits

As stated earlier in Chapter 8, the general rule is that the trustee is prohibited from receiving remuneration or other benefits (financial or otherwise) by virtue of his capacity as a fiduciary. Thus, in the absence of authority, the trustee may not be paid a salary or commission. He is accountable to the beneficiaries for any unauthorised benefits received in his capacity as a trustee because of a conflict of duty and interest. The occasions when a trustee may be authorised to receive remuneration were considered in Chapter 8, to which reference ought to be made.

The same principles apply to other fiduciaries such as agents and directors. In Imageview Management Ltd v Jack (2009), the Court of Appeal decided that an agent was accountable for remuneration and other benefits received in breach of his fiduciary duties owing to his failure to both disclose and obtain the consent of his principal. The effect was that the agent was liable to return to his principal, the profits or benefits received and forfeited his right to all further remuneration from his principal.

CASE EXAMPLE

In his judgment, Jacob LJ posed a series of questions. The first question was:

JUDGMENT

| ‘[W]hether the undisclosed side deal [was] a breach of Imageview’s duty as an agent. Was the side deal None of Mr Jack’s business? Mr Recorder Walker … held that it was indeed Mr Jack’s business: it was not Mr Berry/Imageview’s private and separate arrangement. The basis for such a finding was that Imageview in negotiating a deal for itself had a clear conflict of interest. Put shortly, it is possible that the more it got for itself, the less there would or could be for Mr Jack. Moreover it gave Imageview an interest in Mr Jack signing for Dundee as opposed to some other club where no side deal for Imageview was possible. There is no answer to this. The law imposes on agents high standards. Footballers’ agents are not exempt from these. An agent’s own personal interests come entirely second to the interest of his client. If you undertake to act for a man you must act 100%, body and soul, for him. You must act as if you were him. You must not allow your own interest to get in the way without telling him. An undisclosed but realistic possibility of a conflict of interest is a breach of your duty of good faith to your client. That duty should not cause an agent any problem. All he or she has to do to avoid being in breach of duty is to make full disclosure. … it does not matter whether Mr Berry thought it was all right to make the side deal, as he may have done if a practice of side deals exists in the world of football agents. … [In Rhodes v Macalister (1923) 29 Com. Cas. 19], Scrutton LJ said … |

| The law I take to be this: that an agent must not take remuneration from the other side without both disclosure to and consent from his principal. If he does take such remuneration he acts so adversely to this employer that he forfeits all remuneration from the employer, although the employer takes the benefit and has not suffered a loss by it … But I decide it on the broad principle that whether it causes damage or not, when you are employed by one man for payment to negotiate with another man, to take payment from that other man without disclosing it to your employer is a dishonest act. It does not matter that the employer takes the benefit of his contract with the vendor; that has no effect whatever on the contract with the agent, and it does not matter that damage is not shown. The result may actually be that the employer makes money out of the fact that the agent has taken commission. | |

| … In Keppel v Wheeler [1925] 1 KB 577, Atkin LJ said: | |

| I am quite clear that if an agent in the course of his employment has been proved to be guilty of some breach of fiduciary duty, in practically every case he would forfeit any right to remuneration at all. That seems to me to be well established. On the other hand, there may well be breaches of duty which do not go to the whole contract, and which would not prevent the agent from recovering his remuneration; and if it is found that the agent acted in good faith, and the transaction was completed and the claimant has had the benefit of it, he must pay the commission. | |

| … This is a case of a secret profit obtained because Mr Berry/Imageview was Mr Jack’s agent. And there was a breach of a fiduciary duty because of a real conflict of interest. That in itself would be enough, but there is more: the profit was not only greater than the work done but was related to the very contract which was being negotiated for Mr Jack. Once a conflict of interest is shown, as Atkin LJ said … the right to remuneration goes. Questions 2 and 3 – are further agency fees payable and can the paid fees be recovered? Accordingly, as the courts below held there was a breach of fiduciary duty here. The cases I have cited make it plain that where there is such a breach commission is forfeit – so Mr Jack need pay no more agency fees and is entitled to repayment of the fees paid by him. Question 4 – Can Mr Jack recover all or some of the 3,000 fee received by Imageview? The 3,000 was a secret profit made by a fiduciary. On normal equitable principles it is recoverable, subject to the possibility of a reasonable remuneration deduction. Snell’s Equity 31st edn. puts it this way: | |

| A fiduciary is bound to account for any profit that he or she has received in breach of fiduciary duty. | |

| Question 5 – Should there be a deduction from the secret profit to reflect the value of the work done to make it? … Snell … also sets out the general rules about when an allowance for skill and effort will be made: | |

| A fiduciary who has acted in breach of fiduciary duty and against whom an account of profits is ordered, may nevertheless be given an allowance for skill and effort in obtaining the profit which he has to disgorge where ‘it would be inequitable now for the beneficiaries to step in and take the profit without paying for the skill and labour which has produced it.’ This power is exercised sparingly, out of concern not to encourage fiduciaries to act in breach of fiduciary duty. It will not likely be used where the fiduciary has been involved in surreptitious dealing … although strictly speaking it is not ruled out simply because the fiduciary can be criticised in the circumstances. The fiduciary bears the onus of convincing the court that an accounting of his or her entire profits is inappropriate in the circumstances. | |

| The present case is, of course, one of surreptitious dealing. … I cannot see any reason for exercising the power – one to be exercised sparingly – to make an allowance. The onus of justifying the allowance is far from discharged.’ |

CASE EXAMPLE

| Cobbetts v Hodge [2009] EWHC 786, HC The defendant was a salaried partner with the claimant firm of solicitors. Envirotreat Ltd (EL) was a client of the claimants and had difficulty raising capital for its business. The defendant was instructed to act in relation to the restructuring of EL’s business and the issue of further shares in EL. More than 20 per cent of the new shares were allocated to the defendant, who then retired from the claimants’ firm. The claimants commenced proceedings against the defendant, seeking to claim the shares acquired by the defendant in breach of his fiduciary duties. The defendant denied the claim, and in the alternative argued that if he was required to return the shares he was nevertheless entitled to equitable allowance for the sum paid for the shares, and time and skill expended in enhancing the value of the shares. |

| Held: The High Court held in favour of the claimants. | |

1. Although the employment relationship did not per se create a fiduciary relationship, the nature of the employment might provide the context in which fiduciary duties might arise. The introduction of investors was within the scope of the defendant’s employment. In carrying out these duties the defendant owed fiduciary duties to the claimants. 2. A feature of the fiduciary relationship is a duty on the part of the defendant not to place himself in a position of conflict of duty and interest. In particular, the defendant was prohibited from making a secret profit in carrying out his duties. The opportunity to acquire shares in EL had derived from his employment in the claimants’ firm and amounted to a breach of his duties. 3. Despite the conflict of duty and interest, the court has a wide discretion to give the defendant an allowance for expenditure incurred and for his work and skill in benefiting the trust. But this discretion will not be exercised where the fiduciary has been guilty of dishonesty or bad faith. On the facts, the defendant had not simply omitted to disclose the material facts to the claimants, he had given them a misleading account of the basis of the acquisition of the shares. The result was that no allowance would be granted to the defendant, save for the costs of the shares acquired by the defendant. |

JUDGMENT

| ’The opportunity to acquire the shares came to him by virtue of his employment, and by virtue of his involvement in the issue of the shares as part of his specific duties for LC [the claimants]. Mr Hodge did not simply omit to disclose the arrangement with EL … he gave Mr Rimmer a misleading account of the basis of the acquisition of these shares. Moreover, to permit an allowance in these circumstances would be to encourage fiduciaries to place their own interests ahead of those whom they serve. For both those reasons I decline to order any allowance in the present case, beyond the cost of acquisition of the shares.’ |

| Floyd J |

In FHR European Ventures v Mankarious (2011) the High Court decided that the effect of a breach of the agent’s fiduciary duty in failing to disclose a secret commission is that he will be required to account to the principal for the sum. In addition, the principal is entitled to refuse to pay contractual commission in respect of the impugned transaction and is entitled to bring the agency contract to an end. It is immaterial that no damage was suffered by the principal or that the principal may obtain a benefit as a result of the breach of duty.

CASE EXAMPLE