Constructive Trusts II-The Family Home

Constructive trusts II – the family home

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

■ appreciate the inadequacy of the presumptions of resulting trusts and advancements in order to ascertain the interests of parties in the family home

■ understand the relevant principles that are applicable in determining proprietary interests in the family home

■ comprehend the methods that are available to quantify the interest of a party in shared homes

■ understand the status of ‘nuptial agreements’ freely entered into between parties to a marriage or civil partnership

9.1 Introduction

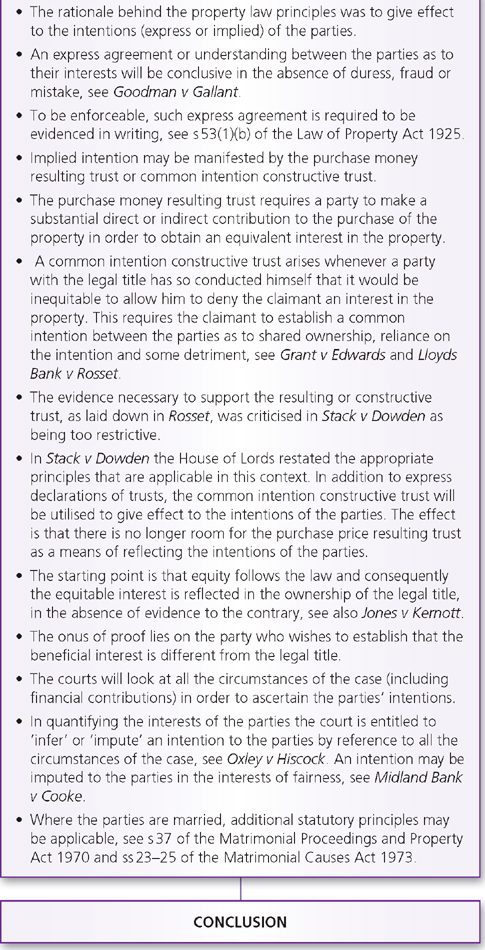

Parties (whether married or unmarried) may contribute to the purchase of a home for themselves, but subsequent events may give rise to a dispute as to the ownership of the property. In these circumstances the courts may step in to settle the matter by (i) giving effect to the express intentions of the parties, (ii) imposing a common intention constructive trust, (iii) creating a resulting trust in exceptional cases, such as investment properties, or (iv) applying statutory principles under the Matrimonial Causes Act 1973 in the event of a divorce, decree of nullity or judicial separation. The property dispute may stem from a breakdown in the relationship between the parties. In this event, the matter will be resolved by the court by reference to the circumstances related to the purchase of the property. But if the dispute arises on the bankruptcy or death of one of the parties this may involve the rights of third parties. As a final introductory point, the status of ante-nuptial and post-nuptial agreements, freely entered into between parties to a marriage or civil partnership, has been resolved by the Supreme Court in favour of validity.

9.2 Proprietary rights in the family home

The presumptions of resulting trusts and advancements in the context of the family home and other family assets were regarded by the middle of the twentieth century as outmoded and best suited for a different society: see Lord Diplock’s judgment in Pettitt v Pettitt (below). In their place the courts have substituted settled principles of property law – the resulting and constructive trusts, although the modern view is that common intention constructive trusts are better suited to reflect the intentions of the parties.

JUDGMENT

| ‘The consensus of opinion which gave rise to the presumptions of advancement and resulting trusts in transactions between husbands and wives is to be found in cases relating to the propertied class of the nineteenth century and the first quarter of the twentieth century among whom marriage settlements were common and it was unusual for the wife to contribute by her earnings to the family income. It was not until after World War II that the courts were required to consider the proprietary rights in family assets of a different social class … It would be an abuse of the legal technique for ascertaining or imputing intention to apply to transactions between the post-war generation of married couples, “presumptions” which are based upon inferences of fact which an entire generation of judges drew as to the most likely intentions of an earlier generation of spouses belonging to the propertied classes of a different social era.’ |

| Lord Diplock in Pettitt v Pettitt [1970] AC 777 |

The Civil Partnership Act 2004 came into force on 5 December 2005 and enables same-sex couples to obtain legal recognition of their relationship by forming a civil partnership. ‘Partners’ include a civil partnership registered under the Civil Partnership Act 2004. A civil partnership is required to be registered in England and Wales at a registered office or approved premise. Civil partners have equal treatment with married couples in a wide range of matters including property rights, taxation including inheritance tax, inheritance of tenancy agreements and recognition under intestacy rules. Consequently, a registered civil partnership, to all intents and purposes, is treated as a marriage.

9.2.1 Legal title in the joint names of the parties

The starting point for ascertaining the existence of a beneficial interest in the family home is the conveyance, or the transfer, of the legal title to the property. The principle is that ‘equity follows the law’ and the equitable interest reflects the nature of the legal ownership. Thus, whether we are dealing with joint or sole legal ownership, the beneficial interest will prima facie be enjoyed by the party(ies) with the legal title. This principle is applicable until the contrary is proved and such evidence may be established by way of an express declaration of trust and, failing this, by way of the implied trust.

If the legal title to property has been conveyed in the joint names of the partners, subject to an express trust of the land for themselves as equitable joint tenants or tenants in common registered in the Land Registry. The express declaration of trust will be conclusive of the equitable interests of the parties, in the absence of fraud, mistake, undue influence or evidence varying the original declaration of trust.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Goodman v Gallant [1986] 2 WLR 236 |

| The claimant and defendant purchased a house which was conveyed in their joint names ‘upon trust to sell … and until sale upon trust for themselves as joint tenants’. The defendant left the house following a dispute between the parties. The claimant gave written notice of severance of the joint tenancy and claimed a declaration to the effect that she was entitled to a three-quarters share in the house. The court decided that in the absence of any claim for rectification or rescission, the express declaration in the conveyance was conclusive as to the intentions of the parties. The notice of severance had the effect of terminating the joint tenancy and substituting a tenancy in common in respect of the beneficial interest. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘If… the relevant conveyance contains an express declaration of trust which comprehensively declares the beneficial interests in the property or its proceeds of sale, there is no room for the application of the doctrine of resulting implied or constructive trusts unless and until the conveyance is set aside or rectified; until that event the declaration contained in the document speaks for itself.’ |

| Slade LJ |

The paramount nature of the express declaration of trust, as compared with the implied trust, may be illustrated by the Court of Appeal decision in Pankhania v Chandegra [2012] EWCA Civ 1438.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Pankhania v Chandegra [2012] EWCA Civ 1438 (Court of Appeal) |

| The appellant (P) appealed against the decision of a High Court judge who dismissed his claim for an order of sale of a residential property in Leicester. The property was purchased in July 1987 for 18,500 in the joint names of the appellant and respondent (C) as joint tenants for themselves as tenants in common in equal shares. The transfer contained an express declaration of trust to that effect. C had insufficient income to obtain a mortgage so P agreed to become a joint mortgagor so that his salary would be taken into account. P had alleged that the property was bought as a home for his uncle to live in and after his death as an investment for P and C (his aunt). C claimed that, notwithstanding the express declaration of trust, there was an understanding between the parties at the time of the purchase that she was to have sole beneficial ownership of the property. Over the years the mortgage had been paid solely by C but between 2005 and 2008 he made mortgage payments to the building society amounting to 2,600. P applied to the court for an order of sale of the property. | |

| The trial judge referred to the constructive trust principles laid down in the definitive cases, Stack vDowden [2007] UKHL17 (see later) and Jones v Kernott [2011] UKSC 53; and decided that a contrary intention to joint beneficial ownership could be inferred from the evidence of the parties’ common intention. The effect was a declaration of sole beneficial ownership in favour of C. P appealed to the Court of Appeal. The court allowed the appeal and decided that the judge had erred in applying the implied trust principles in substitution for an express declaration of trust. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘The parties (both of them of full age) had executed an express declaration of trust over the property in favour of themselves as tenants in common in equal shares and had therefore set out their respective beneficial entitlement as part of the purchase itself. In these circumstances, there was no need for the imposition of a constructive or common intention trust of the kind discussed in Stack v Dowden nor any possibility of inferring one because as Baroness Hale recognised, such a declaration of trust is regarded as conclusive unless varied by subsequent agreement or affected by proprietary estoppel.’ |

| Patten LJ |

CASE EXAMPLE

| Goodman v Carlton [2002] All ER (D) 284 (Apr) |

| The claimant was the son and next of kin of Mr Goodman (G), who died intestate. The defendant, Anita (A), was the surviving legal owner of real property. The legal title to the house was acquired by G and A in 1994. G accepted an offer to purchase the house at a discount. His original intention was to purchase the house alone and register it in his sole name. As G did not have sufficient income to finance a mortgage he arranged to purchase the property with A as co-mortgagee. In 1997 G tentatively instructed his solicitors to transfer the house into his sole name but this was not followed up. Shortly afterwards G died. As surviving joint tenant, A acquired the legal title to the house and G’s son commenced proceedings, claiming that A held the house on trust for G’s estate absolutely. The trial judge decided in favour of the claimant. A appealed to the Court of Appeal. The court dismissed the appeal and decided that the property was held on resulting trust for the claimant, as administrator of G’s estate. A failed to contribute to the purchase of the property and there was no evidence of any agreement, understanding or common intention to share the beneficial ownership with A, who therefore acquired no interest. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘Mr Goodman was the person at whose expense the house was provided. He paid all the deposit. The discount in the price was solely referable to him as sitting tenant. He was to pay (and did in fact pay) all the mortgage payments and all the premiums on the endowment policy. There was no intention that the transfer of the house into joint names should confer a beneficial interest on Anita. It was part of the arrangements undertaken to acquire the house for his sole use, occupation and benefit. Anita’s participation was intended only to be a temporary involvement on the basis of the limited understanding between them. A resulting trust arose by operation of law for the sole benefit of Mr Goodman.’ |

| Mummery LJ |

Alternatively, the parties may declare the terms of the trust outside the conveyance. Provided that s 53(l)(b) of the Law of Property Act 1925 has been complied with (evidenced in writing), the declaration of trust will be conclusive as to the beneficial interests of the parties, in the absence of fraud, mistake or undue influence held out by one party.

The difficulty arises where there is no written evidence of an express declaration of trust but the claimant alleges that the equitable interest is enjoyed in equal shares. In Stack v Dowden the House of Lords restated the principles concerning the occasion when a conveyance of the legal title to property is taken in the joint names of the parties, but without an express declaration of trust as to their respective beneficial interests. As a starting point, the maxims ‘Equity follows the law’ and ‘Equality is equity’ are applicable in order to identify the existence of the equitable interest, subject to evidence to the contrary. Thus, whether we are dealing with joint legal ownership (as in Stack v Dowden) or sole legal ownership (see later), the beneficial interest will prima facie be enjoyed by the party(ies) with the legal title. Until the contrary is proved, the extent of the beneficial interest will also follow the legal title. Thus, where the transfer of the legal title is in joint names then prima facie the beneficial interest will be enjoyed in equal shares until the contrary is proved. The onus of proof is therefore on the party seeking to establish that the beneficial interest is different from the legal title, such as the defendant in the present case.

The contrary may be established where the legal owner(s) expressly declares a trust. Such a declaration is conclusive of the interests of the parties in the absence of fraud, mistake or variation by subsequent agreement: see Goodman v Gallant (above). In Stack v Dowden the court decided that a declaration that the survivor of the two legal owners can give a valid receipt for capital moneys arising on a disposition of the land did not amount to an express declaration of a beneficial joint tenancy. In this respect the court followed Huntingford v Hobbs [1993] 1 FLR 736.

Likewise, on the issue of evidence to the contrary, Baroness Hale in Stack v Dowden raised the question whether the starting point ought to be the presumption or inference of a resulting trust (purchase money resulting trust), i.e. the beneficial ownership being held in the same proportions as the contributions to the purchase price, or by looking at all the relevant circumstances in order to discern the parties’ common intention, reliance and detriment (constructive trust). In Baroness Hale’s view the emphasis in the domestic context has moved away from crude factors of money contributions (resulting trusts) towards more subtle factors of intentional bargain (constructive trusts). Accordingly, strict mathematical calculations as to who paid what at the time of the acquisition of the property may be less significant today. The common intention constructive trust has the consequence of giving effect to the common intentions of the parties. The quantification or valuation of the interests of the parties will reflect a more realistic approach to the intentions of the parties, as opposed to the narrower purchase moneys resulting trust. The common intention constructive trust was advocated in the 1970s by Lord Diplock in Gissing v Gissing and endorsed by Baroness Hale.

JUDGMENT

| ‘A resulting, implied or constructive trust – and it is unnecessary for present purposes to distinguish between these three classes of trust – is created by a transaction between the trustee and the cestui que trust in connection with the acquisition by the trustee of a legal estate in land, whenever the trustee has so conducted himself that it would be inequitable to allow him to deny to the cestui que trust a beneficial interest in the land acquired. And he will be held so to have conducted himself if by his words or conduct he has induced the cestui que trust to act to his own detriment in the reasonable belief that by so acting he was acquiring a beneficial interest in the land.’ |

| Lord Diplock in Gissing v Gissing [1971] AC 886 (emphasis added) |

Where the legal title is taken in the joint names of the parties the presumption is that equity follows the law and the equitable interest is acquired by both parties as joint tenants. The joint tenancy is capable of severance and may be converted into an equitable tenancy in common with the parties becoming entitled to equal shares in equity. If a party wishes to contest this solution and claim a greater interest, he or she has a burden of proving the existence of such interest by way of a common intention constructive trust. The elements of such a constructive trust require evidence that is related to the acquisition of the property, or exceptionally subsequent to such acquisition, of an express or implied intention to share the property, relied on by the claimant to his or her detriment.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Stack v Dowden [2007] UKHL 17, HL |

| The family home (Chatsworth Road) was transferred in 1993 in the joint names of Ms Dowden (defendant) and Mr Stack (claimant). The purchase of the property was for £190,000. This was funded by a mortgage advance of £65,000 for which both parties were liable, the proceeds of sale of £67,000 from the first property (Purves Road, which was registered in the sole name of the defendant) and savings of £58,000 from a building society account in the defendant’s name. The transfer contained no words of trust but included a declaration by the purchasers that the survivor of them was entitled to give a valid receipt for capital moneys. There was no discussion between the parties, at the time of the purchase, as to their respective share in the property. In 2002, owing to the deterioration of the relationship between the parties, the defendant served a notice of severance which had the effect of converting the joint tenancy into a tenancy in common. In April 2003 the parties agreed to a time-limited order in the Family Proceedings Court which excluded Mr Stack from the house and required Ms Dowden to pay him £900 per month which reflected the cost of alternative accommodation. After that order expired Mr Stack effectively accepted Ms Dowden’s decision to exclude him. The result was that Ms Dowden remained in exclusive occupation and Mr Stack continued to pay for alternative accommodation. The claimant petitioned the court for a declaration that the property was held upon trust for the parties as tenants in common in equal shares. The trial judge ruled that the claimant had an interest in the first property and the savings and made an order to the effect that the claimant had an equal share in the property. In addition the court ordered that the defendant pay the claimant £900 per month as occupation rent. The defendant appealed against the order on the ground that the judge had misdirected himself. | |

| The Court of Appeal allowed the appeal and decided that the beneficial interests in the house were held in the proportion of 65 per cent/35 per cent in her favour. Further there was no basis for assessing the compensation to the claimant at 900 per month. The claimant appealed to the House of Lords contending that the trial judge’s original order be restored. | |

| The House of Lords unanimously dismissed Mr Stack’s appeal on the ground that there was no basis for varying the split of beneficial ownership (65 per cent/35 per cent) in favour of the defendant, which arose in 1993 on the acquisition of the Chatsworth Road house. | |

| A declaration as to the receipt for capital moneys in the transfer document could not be construed as an express declaration of trust, following Huntingford v Hobbs [1993] 1 FLR 736. | |

| Having regard to all the circumstances and wishes of the beneficiaries, as the court is obliged to do under s 15 of the Trusts of Land and Appointment of Trustees Act 1996, the court would not award rent to the defendant (Lord Neuberger dissenting). |

JUDGMENT

In Stack v Dowden Lord Neuberger arrived at the same conclusion but by a different route. He adopted the same starting point by regarding the equitable interest(s) as following the legal title(s), subject to evidence to the contrary. However, with regard to rebutting evidence he followed the traditional approach by having regard to the resulting and constructive trusts. Where the parties contributed to the purchase price of the property (including mortgage repayments) the beneficial ownership will be held in the same proportions as the contributions to the purchase price. This is the purchase money resulting trust solution.

student mentor tip

‘Stack v Dowden is pertinent, so read the case in full.’ Pelena, University of Surrey

To summarise, in Stack v Dowden two different approaches as to the interests of the parties were advocated by the Law Lords as manifested by Baroness Hale and Lord Neuberger. Both approaches led to the same result. However, the view expressed by Baroness Hale is widely regarded as a correct statement of the current principles governing the interests in the family home namely, the common intention constructive trust. The Law Commission (2001, Law Com No 274) in its review of the law relating to the property rights of those who share homes commented that: ‘It is widely accepted that the present law is unduly complex, arbitrary and uncertain in its application. It is ill-suited to determining the property rights of those who, because of the informal nature of their relationship, may not have considered their respective entitlements.’ In 2002, the Commission published ‘Sharing homes, a discussion paper’ (2002, Law Com No 278) but failed to recommend any proposals for reform. The Commission declared: ‘It is simply not possible to devise a statutory scheme for the ascertainment and quantification of beneficial interests in the shared home which can operate fairly and evenly across the diversity of domestic circumstances which are now to be encountered.’

In Fowler v Barron [2008] All ER (D) 318 (Apr), the Court of Appeal had the opportunity to consider the scope of the principles laid down in Stack v Dowden. In Fowler v Barron, the Court of Appeal decided that the trial judge had incorrectly concentrated on the parties’ financial contributions and gave disproportionate weight to such a factor. But the crucial factor identified in Stack is not necessarily the amount of the parties’ contributions to the property, but consideration of all the circumstances which may throw light on the parties’ common intentions in relation to ownership of the property.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Fowler v Barron [2008] All ER (D) 318 (Apr) |

| In this case, the parties were in an unmarried relationship for some 23 years from 1983 to 2005. In 1998 they bought the property in issue in Bognor Regis for £64,950 to provide a home for themselves and two children. The parties made a conscious decision to put the property in their joint names but did not take legal advice as to the consequences for doing so. Mr Barron (B), a retired fireman, paid the deposit on the house and arranged a mortgage for £35,000 in the joint names of the parties. B also paid the balance of the purchase price out of the proceeds of sale of his flat. There was no express declaration of trust, although the transfer stated that either surviving party was entitled to give a valid receipt for capital money. B alone paid the mortgage instalments and direct fixed costs of the property, such as council tax and utility bills, out of his pension. Miss Fowler (F) was employed and the judge found that she spent her income on herself and children. There was no joint bank account but the parties executed mutual wills, each leaving their interest in the property to the other. | |

| The relationship between the parties deteriorated and the issue arose as the extent of the parties’ beneficial interest in the property. The trial judge concentrated on the financial contributions of the parties and decided that F did not have a beneficial share in the property. F appealed and the Court of Appeal allowed the appeal, and decided that F had a 50 per cent share in the property, on the ground that the judge had erred in concentrating exclusively on the parties’ financial contributions to the property. The facts as found by the judge were inconsistent with a common intention to exclude F from a beneficial interest. | |

| The judge found that F used her income to spend as she chose, on the other hand, B paid the expenses of acquiring and maintaining the house. | |

| The Court of Appeal decided that, having regard to all the circumstances, the parties’ intentions were that it made no difference to their interests in the house who incurred what expense. On the question of the quantification of the appropriate share of each of the parties in the property the Court of Appeal decided that each case is determined on its own facts. The primary objective of the court is to ascertain the common intention of the parties by reference to the entire course of conduct regarding the house. Where the parties have made unequal contributions to the cost of acquiring their home, there is a thin dividing line between the case where the parties’ shared intention is properly inferred to be ownership in equal shares, and the case where the parties’ common intention is properly inferred to be that the party who contributed less should have a smaller share. In the present case, there was no evidence that the parties had any substantial assets apart from their income and their interests in the property. Thus, the Court of Appeal decided that there was no evidence that the parties intended F to have no share in the house if the relationship broke down. Indeed, by reference to the circumstances of the case the parties’ objective intention was that F was entitled to a half share in the property. |

9.2.2 Investment properties

In Laskar v Laskar [2008] All ER (D) 104 (Feb), the Court of Appeal decided that the Stack v Dowden principles were not applicable to the acquisition of investment properties, i.e. properties bought for rental income and capital appreciation. In such cases the traditional resulting trust principles with their focus on mathematical computations of the contributions made by the individuals were prima facie applicable to ascertain the interests of the parties to the dispute.

CASE EXAMPLE

JUDGMENT

| ’The presumption of joint ownership … It was argued that this case was midway between the cohabitation cases of co-ownership where property is bought for living in, such as Stack, and arm’s-length commercial cases of co-ownership, where property is bought for development or letting. In the latter sort of case, the reasoning in Stack would not be appropriate and the resulting trust presumption still appears to apply. In this case, the primary purpose of the purchase of the property was as an investment, not as a home. In other words this was a purchase which, at least primarily, was not in “the domestic consumer context” but in a commercial context. To my mind it would not be right to apply the reasoning in Stack to such a case as this, where the parties primarily purchased the property as an investment for rental income and capital appreciation, even where their relationship is a familial one… |

| The discount When it comes to assessing the contributions to the purchase price the appellant argues either that no account should be taken of the discount of £29,415 or that it should be attributable equally to both parties. I do not agree. In the absence of authority the position seems to me to be this. The reason the property could be bought at a discount – indeed, the reason the property could be bought at all-was that the respondent had been the secure tenant of the property and had resided there in that capacity for a substantial period … It was therefore the respondent, and solely the respondent, to whom the discount of £29,415 could be attributed… | |

| The effect of taking the mortgage in joint names There is obvious force in the appellant’s contention that, as she and the respondent took out a mortgage in joint names for £43,000, for which they were jointly and separately liable, in respect of a property which they jointly owned, this should be treated in effect as representing equal contributions of £21,500 by each party to the acquisition of the property. It is right to mention that I pointed out in Stack that, although simple and clear, such a treatment of a mortgage liability might be questionable in terms of principle and authority. | |

| However, it appears to me that in this case it would be right to treat the mortgage loan of £43,000 as representing a contribution of £21,500 by each of the parties as the two joint purchasers of the property. | |

| There was no agreement or understanding between the parties that one or other of them was to be responsible for the repayments. The repayments had effectively been met out of the income from the property, which, so far as one can gather, was intended from the inception, and the property was, as I have mentioned, primarily purchased and has been retained as an investment. In those circumstances I would have thought that there was a very strong case for apportioning the mortgage equally between the parties when it comes to assessing their respective contributions to the purchase price… | |

| Conclusions on the beneficial interest In light of these conclusions on these three points, I am of the view that it would be right to substitute for the judge’s decision that the appellant has 4.28 per cent of the beneficial interest in order that she has a 33 per cent interest in the property. I arrive at that conclusion on the basis that the respondent’s contribution was the aggregate of £21,500 (half of the mortgage) £29,500 (the discount) and £3,600 (her share of the balance), and that the appellant’s contribution was £21,500 (half the mortgage) and £3,400 (her share of the balance). That produces a share of 33%.’ | |

| Lord Neuberger |

In Williams v Parris [2008] EWCA Civ 1147, the Court of Appeal decided, in accordance with the principles laid down in Lloyds Bank v Rosset (see later), that once the claimant had established a common intention or agreement to share a beneficial interest in property, a constructive trust will arise if the claimant had acted to his detriment or significantly altered his position in reliance on the agreement or understanding. It was not necessary for the claimant to proceed further and establish that the arrangement or agreement had involved the making of a bargain between the parties, and that the claimant had performed his part of that bargain.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Williams v Parris [2008] EWCA Civ 1147 |

| In Williams the claimant ran into financial problems and entered into an individual voluntary arrangement with his creditors. The defendant was offered an opportunity to purchase two flats (flats 1 and 6) and discussed this with the claimant. The claimant was unable to contribute, partly as a result of the IVA. Despite that, the claimant’s case was that they agreed to proceed with the purchase of the flats as a joint venture. The defendant would buy them, but on the basis that flat 6 would belong beneficially to him (the claimant). The defendant bought both flats in his own name. The claimant issued proceedings seeking a declaration that the defendant held flat 6 on trust for him absolutely. On the evidence the judge found that an informal agreement had been reached between the parties that the flats would be purchased by the defendant on the basis that they would have an equal interest. That would take the form of each one having one flat in due course. The claimant had supplied what he could, namely, labour to begin with, later on some money and undoubtedly maintenance charges. The defendant appealed on the ground that the party claiming the benefit of the trust should be able to show not merely that there was an agreement between him (claimant) and the legal owner that he should have a beneficial interest, but also that he had acted under that agreement in the manner provided for in the agreement. | |

| The Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal and decided that once a finding of express arrangement or agreement had been made, all that the claimant to a beneficial share under a constructive trust needed to show was that he had acted to his detriment or had significantly altered his position in reliance on the agreement. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘[Referring to Lord Bridge’s remarks in Rosset:] What he said was advanced by way of express guidance to trial judges. The first type of case he identified was a case such as this one; and he made it plain that, once a finding of an express arrangement or agreement has been made, all that the claimant to a beneficial share under a constructive trust needs to show is that he or she has acted to his or her detriment or significantly altered his or her position in reliance on the agreement…. That amounts to solid support for the approach reflected in Grant (1986) and for the way in which the Recorder directed himself in the present case. It implicitly rejects any suggestion that might be derived from Lord Diplock’s remarks in Gissing (1971)… that it is necessary to show that the arrangement or agreement involved the making of something in the nature of a bargain between the parties, and that the claimant has performed his part of that bargain.’ |

| Rimer LJ |

In accordance with the principles concerning investment properties it follows that the starting point is the ownership of the legal title. If the legal title is vested in joint parties the equitable interest will mirror this interest. If the legal title is vested in the name of one party the starting point is that the equitable interest will follow the legal title. A claimant who alleges to the contrary will be put to proof to establish that a different proportion of interest has been acquired by him. If there is no evidence in writing the claimant will be required to establish an implied trust in his favour, resulting or constructive. If the purchase moneys were provided solely by the party without the legal title it may be necessary to establish a common intention constructive trust, i.e. the common intention of the parties is that the claimant acquires the equitable interest and he relied on this intention to his detriment, see Agarwola v Agarwala (2013).

CASE EXAMPLE

| Agarwala v Agarwala [2013] Unreported (CA) |

| The appellant (J) was the sister-in-law of the respondent (S). S identified an investment property which he proposed to purchase in the name of his friend, Andy Prior, a builder, subject to a trust deed. This arrangement fell through and S approached J about the investment potential of the property stating that it was a good deal but he did not have the credit rating to purchase it. She agreed and in April 2007 the property was purchased. The property was to be used as a ‘bed and breakfast’ (B&B) business. The purchase, subject to a mortgage, was made in J’s name (legal title) and it was agreed that S would pay the mortgage instalments and operate and manage the B&B. The parties fell out in July 2008 and J’s husband (H) took over the day-to-day running of the business and changed the locks to exclude S from the premises. S forged J’s signature on the lease and trust deed to benefit himself and back dated the documents to 2007. S’s deceit was detected, and although he was arrested, he was not prosecuted. | |

| S issued proceedings claiming the beneficial ownership. The parties agreed that there was a clear, oral agreement or understanding between them as to the terms on which they bought, held and used the property but the details of that agreement was disputed by the parties. J’s case was that the property and business were hers beneficially and that S had agreed to manage the conversion and operate the business at no charge. The benefit to S was that he would have been entitled to accommodate surplus guests from his other B&B business. S’s case was that J had agreed to help him to purchase the property because of his bad credit rating and that since he had provided the money for the conversion and mortgage payments, the property and business were his beneficially. Thus, S alleged that J held the property as bare trustee for him as absolute beneficial owner. | |

| The judge ruled that S’s account of the terms of the agreement was more credible and that J held the property on constructive trust for S, based on a common understanding, reliance and detriment in accordance with the principles laid down in the Stack v Dowden [2007] UKHL 17. J appealed to the Court of Appeal against this ruling. The court dismissed the appeal and decided that the trial judge had correctly directed himself on the appropriate weight to be attached to each party’s version of the agreement. No weight was attached to the forged documents executed by S in deciding on S’s credibility. The money and work put in by S in converting, setting up and running the business was to his detriment and supported his contention. Accordingly, J held the property on constructive trust for S. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘It was common ground that this was a business venture in which there was an agreement as to the terms on which the property was to be bought, held and used. The fact that the mortgage was in [J’s] name and that she paid the instalments was of little help in deciding the issue of beneficial ownership if [J] was, in effect, a conduit for the payment of the instalments out of the profits of the business venture.’ |

| Sullivan LJ |

9.2.3 Legal title in the name of one party only

Where the legal title to property has been conveyed in the name of one party only, and his or her partner wishes to claim a beneficial interest, the claimant is required to establish the existence of a common intention constructive trust. The presumptions of resulting trust and advancement will not be readily adopted in order to quantify the interests of the parties because such presumptions have outlived their usefulness in this context. It was not until after the Second World War that the courts were required to consider the proprietary rights in family assets of a different social class. It was considered to be an abuse of legal principles for ascertaining or imputing intention, to apply to transactions between the post-war generation of married couples artificial ‘presumptions’ as to the most likely intentions of a culturally different generation of spouses in the nineteenth century, per Lord Diplock (above). These sentiments were expressed by the House of Lords in two definitive decisions: Pettitt v Pettitt [1970] AC 777 and Gissing v Gissing [1971] AC 886.

Having dispelled notions of the presumed resulting trust and advancement the House of Lords replaced the presumptions with common intention constructive trusts. The effect is that where the legal title is vested in the name of one party the inference is that equity follows the law and the party with the legal title is prima facie solely entitled to the equitable interest. If the party without the legal title wishes to claim an interest in the property, he or she bears the legal burden of proving that both parties had an intention to give the claimant an interest in the property which was relied on to his or her detriment. This solution, with the appropriate adaptation, is similar to the principles that are applicable to transfers of the property in joint names mentioned earlier.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Pettitt v Pettitt [1970] AC 777 |

| Mrs Pettitt purchased a cottage with her own money and had the legal title conveyed in her name. Mr Pettitt from time to time redecorated the property, expending a total of £725. On a breakdown of the marriage he claimed a proportionate interest in the house (£1,000 pro rata value). The court decided that Mr Pettitt’s expenditure was not related to the acquisition of the house. In the absence of an agreement or understanding, his expenditure was to be treated as a gift. The court decided that settled principles of property law were applicable in this context. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘Where the acquisition or improvement is made as a result of contributions in money or money’s worth by both spouses acting in concert the proprietary interests in the family asset resulting from their respective contributions depend upon their common intention as to what those interests should be. |

| In the present case we are concerned not with the acquisition of a matrimonial home on mortgage, but with improvements to a previously acquired matrimonial home. | |

| It is common enough nowadays for husbands and wives to decorate and to make improvements in the family home themselves, with no other intention than to indulge in what is now a popular hobby, and to make the home pleasanter for their common use and enjoyment. If the husband likes to occupy his leisure by laying a new lawn in the garden or building a fitted wardrobe in the bedroom while the wife does the shopping, cooks the family dinner or bathes the children, I, for my part, find it quite impossible to impute to them as reasonable husband and wife any common intention that these domestic activities or any of them are to have any effect upon the existing proprietary rights in the family home on which they have undertaken. It is only in the bitterness engendered by the break-up of the marriage that so bizarre a notion would enter their heads.’ | |

| Lord Diplock |

CASE EXAMPLE

| Gissing v Gissing [1971] AC 886 |

| Mr Gissing purchased the matrimonial home in his name out of his own resources. Mrs Gissing paid £220 for furnishings and laying a lawn. There was no common understanding as to the beneficial interest in the house. On a breakdown of the marriage, the question arose as to the beneficial ownership of the house. The court decided that Mrs Gissing was not entitled to an interest in the house, for she had made no contributions to the purchase price. |

JUDGMENT

Likewise, Lord Walker in Stack v Dowden disapproved of the purchase money resulting trust principles in the context of ownership of the family home in favour of the broader constructive trust rules. Contributions to the purchase price in money or money’s worth may be relevant in determining the existence of a common intention.

JUDGMENT

| ‘In a case about beneficial ownership of a matrimonial or quasi-matrimonial home (whether registered in the name of one or two legal owners) the resulting trust should not in my opinion operate as a legal presumption, although it may (in an updated form which takes account of all significant contributions, direct or indirect, in cash or in kind) happen to be reflected in the parties’ common intention.’ |

| Lord Walker |

9.3 Nature of the trust

In the domestic context, the notion of the ‘purchase money’ resulting trust has been finally castigated in favour of the common intention constructive trust in a long line of decisions culminating with Stack v Dowden and Jones v Kernott (see later). The constructive trust regime is regarded as an appropriate vehicle that reflects the genuine intentions of the parties at the time of the acquisition of the property, or exceptionally at a later date.

The constructive trust will be created whenever the trustee has so conducted himself that it would be inequitable to allow him to deny to the beneficiary an equitable interest in the land acquired. He will be treated as having conducted himself inequitably if, by his words or conduct, he had induced the beneficiary to act to his own detriment in the reasonable belief that by so acting he will acquire a beneficial interest in the land. In other words, the court gives effect to the implied trust that reflects the common intention of the parties that if each acts in the manner provided for in the agreement the beneficial interests in the matrimonial home will be held as they have agreed; for example, if both the husband and wife contributed to the purchase of the house but the legal title to the property was placed solely in the name of the husband, the wife will need to establish that it would be inequitable for the husband to deny her a share in the property. This would be the case if the court is satisfied that it was the common intention of both spouses that the contributing wife should have a share in the beneficial interest and that her contributions were made upon this understanding. The court, in the exercise of its equitable jurisdiction, would not permit the husband in whom the legal estate was vested and who had accepted the benefit of the contributions to take the whole beneficial interest merely because, at the time the wife made her contributions, there had been no express agreement as to how her share in it was to be quantified. The same principles apply where the legal title is conveyed in the joint names of the parties. The presumption is in favour of a legal and equitable joint tenancy until the contrary is proved.

The intentions of the parties are determined objectively, by reference to their statements and conduct. The court is required to draw inferences from such evidence and make value judgments as to their intentions. This is the position even though a party did not consciously formulate that intention in his own mind or may have acted with some different intention which he did not communicate to the other party. The subjective intentions of the parties are not decisive: more so, if such intention has not been communicated to the other party.

The time for drawing an inference as to what the parties said and did which led up to the acquisition of a matrimonial home is on a different footing from what they said and did after the acquisition was completed. The material time for the court to draw inferences from the conduct of the parties is up to and including the time of the acquisition of the property. In exceptional circumstances, subsequent evidence may be relevant only if it is alleged that there was some subsequent fresh agreement, acted upon by the parties, to vary the original beneficial interests created when the matrimonial home was acquired. In other words, what the parties said and did after the acquisition was completed will be relevant if it is explicable only upon the basis of their having manifested to one another at the time of the acquisition some particular common intention as to how the beneficial interests should be held.

CASE EXAMPLE

| James v Thomas [2008] 1 FLR 1598 |

| The claimant, who did not have the legal title to the property, failed to discharge the burden of proof cast on her to demonstrate, based on evidence related to the entire course of dealing, that she acquired an interest in the property. In this case, Miss James entered into a relationship with the defendant and subsequently moved into the house owned by the defendant. Miss James worked without remuneration with Mr Thomas in his business as an agricultural building and drainage contractor. The couple’s household, living and personal expenses were paid from a current bank account in Mr Thomas’s sole name that also served as the business account. After a number of years the bank account was put into the couple’s joint names and the business was carried on as a partnership between the couple, although Miss James was no longer working in it on a full time basis. Over the years the couple carried out extensive works of renovation at the property, funded by income generated by the business. Mr Thomas had observed that such works benefited both of them, and that Miss James would be well provided for on his death. Some years later the relationship broke down, Miss James moved out, and the partnership was dissolved by notice served by Miss James. The latter claimed an interest in the property on the ground of a constructive trust or alternatively proprietary estoppel. The judge dismissed her claim and she appealed. The Court of Appeal dismissed her appeal but observed that the common intention necessary to found a constructive trust could be formed at any time before, during or after the acquisition of a property; a constructive trust could therefore arise some years after the property had been acquired by, and registered in the sole name of, one party. However, in the absence of an express post-acquisition agreement, the court would be slow to infer from conduct alone that the parties intended to vary existing beneficial interests established at the time of acquisition. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘Did the judge err in law? Taken out of context, the judge’s observation that a constructive trust can only arise when land is purchased for the use of two or more persons, only one of whom is registered as the legal owner provides powerful support for the submission that he misunderstood the law in this field. In the first place, the observation (as a generality) is plainly incorrect: a constructive trust can arise in circumstances where two parties become joint registered proprietors. But that, of course, is not this case. More pertinently, if the circumstances so demand, a constructive trust can arise some years after the property has been acquired by, and registered in the sole name of, one party who (at the time of the acquisition) was, beyond dispute, the sole beneficial owner: Gissing v Gissing [1971] AC 886, Bernard v Josephs [1982] Ch 391. But, as those cases show, in the absence of an express post-acquisition agreement, a court will be slow to infer from conduct alone that parties intended to vary existing beneficial interests established at the time of acquisition. |

| The judge was plainly correct, on the facts in this case, to hold that there was no common intention, at or before the acquisition of the property by Mr Thomas in 1985 or 1986, that Miss James should have some beneficial share: as he found, the parties had not then met. It follows that, unless the judge is to be taken to have accepted that, as a matter of law, it would be sufficient to establish that such an intention arose in or after 1989, there would have been no purpose in going on to consider whether the evidence did establish a common intention that Miss James should have a share. But, plainly, he did consider that question. He referred, in terms to the absence of an allegation by Miss James, that there were any discussions between the parties either at the time of the acquisition or subsequently to the effect that they had an agreement or an understanding that the property would be shared [emphasis added]. To my mind, the better view (when the judgment is read as a whole) is that the judge did recognise that there was a need to consider (in relation to constructive trust as well as in relation to proprietary estoppel) whether the parties formed a common intention, in or after 1989, that Miss James should have a beneficial share in the property. Accordingly – although not without hesitation – I reject the submission that the judge erred in law.’ | |

| Chadwick LJ |

9.3.1 Common intention

The key concept that underpins the establishment of an interest in the family home today is the single regime of the common intention constructive trust. The purchase money resulting trust principles will not be adopted to identify and quantify the interests of the parties. The time for deciding on the existence of the parties’ intention is at the time of the purchase of the property or exceptionally at some later date. This is the position whether the legal title to the property is placed in the joint names of the parties or in the sole name of one party. In both cases the rule is that equity follows the law. The effect is that in the case of joint names legal ownership the inference is that the parties are joint tenants and in cases of sole legal ownership the prima facie rule is that the party with the legal title is the equitable owner. If a party wishes to claim an interest different from the prima facie rule he or she bears the legal burden of proving the existence of a common intention of the parties that he or she has an equitable interest, or a greater interest, than is reflected by reference to the legal title, relied on by such party to his or her detriment. This intention is determined objectively by reference to the conduct of the parties.

JUDGMENT

| ‘The time has come to make it clear, in line with Stack v Dowden (see also Abbott v Abbott [2007] UKPC 53, [2007] 2 All ER 432, [2008] 1 FLR 1451), that in the case of the purchase of a house or flat in joint names for joint occupation by a married or unmarried couple, where both are responsible for any mortgage, there is no presumption of a resulting trust arising from their having contributed to the deposit (or indeed the rest of the purchase) in unequal shares. The presumption is that the parties intended a joint tenancy both in law and in equity. But that presumption can of course be rebutted by evidence of a contrary intention, which may more readily be shown where the parties did not share their financial resources.’ |

| Baroness Hale in Jones v Kernott [2011] UKSC 53; see later |

The existence of a common intention may be express or implied by reference to the circumstances of each case. The court is required to interpret the surrounding facts with a view to ascertaining the intentions of the parties with regard to a share in the home. In Lloyds Bank v Rosset (1990), Lord Bridge opined that evidence of express intention is based on express discussion between the parties, even though the terms of the discussion may not be precisely recalled. In this respect the discussions need not be as to the precise interest to be acquired by the parties, provided that they are centred on the existence of an interest. With regard to implied or inferential common intention, Lord Bridge advocated the test of looking at the conduct of the parties and decided that substantial direct financial contributions to the purchase price, by paying the deposit or mortgage instalments on the house, may be sufficient.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Lloyds Bank v Rosset [1990] 1 All ER 1111, HL |

| A semi-derelict farmhouse was conveyed in the name of the husband but the wife spent a great deal of time in the house supervising the work done by builders. She also did some decorating to the house. Unknown to the wife, her husband had taken out an overdraft with the bank. The couple later separated but the wife remained in the house. The husband was unable to repay the overdraft, with the result that the bank started proceedings for the sale of the property. The wife resisted the claim on the ground that she was entitled to a beneficial interest in the house under a constructive trust. The trial judge and the Court of Appeal decided that the husband held the property as constructive trustee for wife and himself. The bank appealed to the House of Lords. | |

| Held: In favour of the bank on the ground that the wife had no beneficial interest in the property. There was no understanding between the parties that the property was to be shared beneficially, coupled with detrimental action by the claimant, nor had there been direct contributions to the purchase price. In any event, the court decided that the monetary value of the wife’s work was trifling compared with the cost of acquiring the house. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘The first and fundamental question which must always be resolved is whether, independently of any inference to be drawn from the conduct of the parties in the course of sharing the house as their home and managing their joint affairs, there has at any time prior to acquisition, or exceptionally at some later date, been any agreement, arrangement or understanding reached between them that the property is to be shared beneficially. The finding of an agreement or arrangement to share in this sense can only, I think, be based on evidence of express discussions between the partners, however imperfectly remembered and however imprecise their terms may have been. Once a finding to this effect is made it will only be necessary for the partner asserting a claim to a beneficial interest against the partner entitled to the legal estate to show that he or she has acted to his or her detriment or significantly altered his or her position in reliance on the agreement in order to give rise to a constructive trust or a proprietary estoppel. |

| In sharp contrast with this situation is the very different one where there is no evidence to support a finding of an agreement or arrangement to share, however reasonable it might have been for the parties to reach such an arrangement if they had applied their minds to the question, and where the court must rely entirely on the conduct of the parties both as the basis from which to infer a common intention to share the property beneficially and as the conduct relied on to give rise to a constructive trust. In this situation direct contributions to the purchase price by the partner who is not the legal owner, whether initially or by payment of mortgage instalments, will readilyjustify the inference necessary to the creation of a constructive trust. But, as I read the authorities, it is at least extremely doubtful whether anything less will do.’ | |

| Lord Bridge (emphasis added) |

It has been recognised that Lord Bridge’s view of the evidence of implied common intention by reference solely to direct financial contributions to the purchase price may have been too restrictive and narrow. Instead the courts tend to adopt a more holistic approach to evidence of common intention by considering circumstances other than financial contributions. In Stack v Dowden, Baroness Hale identified a number of non-financial factors that may be considered by the courts. These include the purpose of the acquisition of the home, whether there were any children of the relationship, the obligations undertaken towards the children, how the parties arranged their finances etc.

JUDGMENT

| ‘In law, context is everything and the domestic context is very different from the commercial world. Each case will turn on its own facts. Many more factors than financial contributions may be relevant to divining the parties’ true intentions. These include: any advice or discussions at the time of the transfer which cast light upon their intentions then; the reasons why the home was acquired in their joint names; the reasons why (if it be the case) the survivor was authorised to give a receipt for the capital moneys; the purpose for which the home was acquired; the nature of the parties’ relationship; whether they had children for whom they both had responsibility to provide a home; how the purchase was financed, both initially and subsequently; how the parties arranged their finances, whether separately or together or a bit of both; how they discharged the outgoings on the property and their other household expenses. When a couple are joint owners of the home and jointly liable for the mortgage, the inferences to be drawn from who pays for what may be very different from the inferences to be drawn when only one is the owner of the home. The arithmetical calculation of how much was paid by each is also likely to be less important. It will be easier to draw the inference that they intended that each should contribute as much to the household as they reasonably could and that they would share the eventual benefit or burden equally. The parties’ individual characters and personalities may also be a factor in deciding where their true intentions lay … At the end of the day, having taken all this into account, cases in which the joint legal owners are to be taken to have intended that their beneficial interests should be different from their legal interests will be very unusual.’ |

| Baroness Hale in Stack v Dowden | |

| ’Lord Bridge’s extreme doubt whether anything less will do was certainly consistent with many first instance and Court of Appeal decisions, but I respectfully doubt whether it took full account of the views (conflicting though they were) expressed in Gissing v Gissing (especially Lord Reid [1971] AC 886 … and Lord Diplock …). It has attracted some trenchant criticism from scholars as potentially productive of injustice. Whether or not Lord Bridge’s observation was justified in 1990, in my opinion the law has moved on, and your Lordships should move it a little more in the same direction.’ | |

| Lord Walker in Stack v Dowden |

It follows that not all applications of money towards the purchase price of the home would entitle the payor to an interest in the house. The provision of the money may constitute a gift or loan to the purchaser divorced from an arrangement or requirement connected with the purchase of the property. In these circumstances the donor or lender may be unable to establish the existence of an agreement linked to the purchase of the property.

9.3.2 Domestic duties

It follows that domestic duties undertaken by a party (such as caring for and bringing up the children), unconnected with a common intention to share the property in reliance on such duties, are insufficient to create an interest in the property.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Burns v Burns [1984] 1 All ER 244 |

| The defendant bought a house in his sole name with the assistance of a mortgage. The claimant made no financial contributions to the purchase of the house but gave up paid employment in order to perform the duties of bringing up their children. The defendant gave her a generous housekeeping allowance and did not ask her to contribute to household expenses. Subsequently, the claimant became employed and used her earnings for household expenses and to purchase fixtures and fittings. Ultimately, the claimant left the defendant and claimed a beneficial interest in the house. The court rejected the claim and held that the claimant had failed to prove that she had made a contribution, directly or indirectly, to the acquisition of the property, and therefore did not have an interest in the property. A common intention that the claimant had acquired an interest in the property cannot be imputed to the parties on the basis that the claimant lived with the defendant for 19 years, brought up the children and did a fair share of domestic duties. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘So far as housekeeping expenses are concerned, I do not doubt that (the house being bought in the man’s name) if the woman goes out to work in order to provide money for the family expenses, as a result of which she spends her earnings on the housekeeping and the man is thus able to pay the mortgage instalments and other expenses out of his earnings, it can be inferred that there was a common intention that the woman should have an interest in the house – since she will have made an indirect financial contribution to the mortgage instalments. But that is not this case. |

| But, one asks, can the fact that the plaintiff performed domestic duties in the house and looked after the children be taken into account? The mere fact that parties live together and do the ordinary domestic tasks is, in my view, no indication at all that they thereby intended to alter the existing property rights of either of them.’ | |

| Fox LJ |

9.3.3 Indirect contributions

Lord Bridge in Rosset made no reference to the significance of indirect contributions to the purchase of the property. It is arguable that this was an oversight on the part of Lord Bridge and not an abolition of such contributions. Indirect contributions to the purchase price of the house (like direct contributions) would equally give the party contributing to the purchase an interest in the property. The claimant may acquire an interest in the property by making a substantial indirect contribution to the acquisition of the property (including mortgage repayments) if he succeeds in proving that such contributions were by arrangement between the parties. This arrangement may be achieved by an undertaking between the parties to the effect that the claimant agrees to pay the household expenses on condition that the legal owner pays the mortgage instalments. In short, a link between the mortgage payments and the expenses undertaken by the claimant is required to be established and the claimant’s expenses are required to be of a substantial nature (per Lord Pearson in Gissing v Gissing (1971)):

JUDGMENT

| ‘Contributions are not limited to those made directly in part payment of the price of the property or to those made at the time when the property is conveyed into the name of one of the spouses. For instance there can be a contribution if by arrangement between the spouses one of them by payment of the household expenses enables the other to pay the mortgage instalments.’ |

The concept of indirect contributions may be illustrated by the Court of Appeal decision in Grant v Edwards (1986):

CASE EXAMPLE

| Grant v Edwards [1986] Ch 638 |

| The claimant, a woman who lived with the defendant, was given a false reason for not having the house put in their joint names. The woman made substantial contributions to the family expenses in the hope of acquiring an interest in the house. The expenses undertaken by the woman enabled the man to keep up the mortgage instalments. The claimant applied to the court for a declaration concerning an interest in the house. The court decided that the claimant was entitled to a half-share in the property. She would not have made the substantial contributions to the housekeeping expenses, which indirectly related to the mortgage instalments, unless she had an interest in the house. This was the inevitable inference of the claimant’s conduct which established a common intention and reliance to her detriment. The court reviewed the earlier case of Eves v Eves [1975] 1 WLR 1338 and declared that that case involved indirect contributions in kind made in reliance on a promise by the legal owner to grant her an equitable interest in the property. |

In Grant v Edwards (1986) two Lords Justices of Appeal disagreed as to the type of conduct that may constitute indirect contributions. Nourse LJ adopted a narrow interpretation of such conduct. In his view it is conduct in respect of which the actor could not have been reasonably expected to embark unless he or she had an interest in the house. On the other hand, Browne-Wilkinson LJ was prepared to adopt a wider interpretation of conduct that may give rise to indirect contributions. In his view, once a common intention is established, ‘any act done by her to her detriment relating to the joint lives of the parties is … sufficient to qualify. The acts do not have to be referable to the house.’

The disputed intention of the parties may be established by direct evidence of an express agreement in writing between the parties, or may be an inferred common intention from the conduct of the parties. Direct or indirect substantial financial contributions to the acquisition of the house (including the mortgage instalments) will have this effect. Indeed, contributions may be relevant for four different purposes:

(a) in the absence of direct evidence of intention, as evidence from which the parties’ intentions can be inferred;

(b) as corroboration evidence of the intention of the parties;

(c) to show that the claimant has acted to his detriment in reliance on the common intention;

(d) to quantify the extent of the beneficial interest.

During the 1970s and early 1980s the Court of Appeal, in a series of decisions, advocated its own peculiar solution to disputes involving the family home. Its approach was based on a liberal interpretation of justice and good conscience. The court attempted to do justice between the parties on a case-by-case basis, by declaring property rights based on fairness. This system of ‘palm tree’ justice, called the ‘new model constructive trust’, had the counterproductive effect of creating unpredictable property rights which might affect third parties. Eves v Eves is an illustration of this approach.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Eves v Eves [1975] 1 WLR 1338, CA |

| An unmarried couple bought a house which was conveyed in the name of the man (defendant) instead of both parties, on the ground that the plaintiff (as suggested by the defendant) was under 21. She bore him two children and did a lot of heavy work in the house and garden before he left her for another woman. The plaintiff applied to ascertain her share of the house. | |

| The court found in favour of the plaintiff and awarded her a quarter-share of the house on the ground that the property was acquired and maintained by both parties for their joint benefit. | |

| In Grant v Edwards, the Court of Appeal reviewed Eves v Eves and considered the case as an illustration of conduct manifesting a common intention between the parties which was relied on by the claimant. Nourse LJ in Grant v Edwards made the following observations concerning Eves v Eves. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘It would be possible to take the view that the mere moving into the house by the woman amounted to an acting upon the common intention. But that was evidently not the view of the majority in Eves v Eves [1975] 1 WLR 1338. And the reason for that may be that, in the absence of evidence, the law is not so cynical as to infer that a woman will only go to live with a man to whom she is not married if she understands that she is to have an interest in their home. So what sort of conduct is required? In my judgment it must be conduct on which the woman could not reasonably have been expected to embark unless she was to have an interest in the house. If she was not to have such an interest, she could reasonably be expected to go and live with her lover, but not, for example, to wield a 14 lb sledge hammer in the front garden. In adopting the latter kind of conduct she is seen to act to her detriment on the faith of the common intention.’ |

| Nourse LJ |

In the post-Rosset decision of Le Foe v he Foe [2001] All ER (D) 325 (Jun), the High Court analysed Lord Bridge’s judgment and decided that he did not intend to exclude indirect contributions.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Le Foe v Le Foe [2001] All ER (D) 325 (Jun) |

| The parties were married and the family home was put in the husband’s sole name with the assistance of a mortgage. The wife was in paid employment and assisted the husband in the repayment of the mortgage. On a breakdown of the marriage the issue arose as to the extent of the wife’s interest in the house. The court decided that by virtue of the wife’s indirect contributions to the mortgage repayments the court was entitled to infer that the parties had a common intention that the wife would acquire an interest in the property. This was quantified at 50 per cent. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘In my view what Lord Bridge is saying is that in the second class of case to which he is adverting, namely where there is no positive evidence of an express agreement between the parties as to how the equity is to be shared, and where the court has fallen back on inferring their common intention from the course of their conduct, it will only be exceptionally that conduct other than direct contributions to the purchase price, either in cash to the deposit, or by contribution to the mortgage instalments, will suffice to draw the necessary inference of a common intention to share the equity.’ |

| Nicholas Mostyn QC |

9.3.4 The unwarranted requirement for express discussions between the parties

Lord Bridge’s insistence in Rosset that an express agreement between the parties as to an interest in the home may be gained only by means of express discussion appears to be over-simplistic, for an agreement or understanding may be inferred from conduct. Generally, in order to establish an agreement between two parties the courts do not insist on evidence of oral discussions between the parties. Oral discussion ordinarily is a significant factor to be taken into consideration but ought not to be the only consideration.

In Hammond v Mitchell [1991] 1 WLR 1127 the High Court adopted the narrow approach of express discussion as evidence of the intention of the parties as laid down by Lord Bridge in Rosset (1990).

CASE EXAMPLE

JUDGMENT

| ‘In relation to the bungalow there was express discussion which, although not directed with any precision as to proprietary interests, was sufficient to amount to an understanding at least that the bungalow was to be shared beneficially.’ |

| Waite J |

Similarly, in Springette v Defoe [1992] 2 FLR 388, the court adhered rigidly to the Rosset (1990) principles.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Springette v Defoe [1992] 2 FLR 388 |

| The parties lived as man and wife in a council house. In 1982, they made a formal offer to purchase the house for £14,445, which represented a discount of 41 per cent because the claimant, Miss Springette (S), had been a council tenant for 11 years or more. They bought the house jointly with the aid of a mortgage of £12,000. By agreement, they each contributed 50 per cent of the mortgage instalments. The balance of the purchase price was provided by S. The legal title was registered in their joint names but no quantification of their interests was registered in the Land Registry. During 1985, the relationship between the parties became strained and the defendant (D) left the home. S claimed that she was entitled to a 75 per cent share of the proceeds of sale of the house, as represented by her contribution to the purchase. The learned Recorder decided that the beneficial interests were shared equally, despite the lack of evidence of any discussion concerning this issue. S appealed to the Court of Appeal. The interests of the parties were determined by reference to the contributions made. There was no evidence which had the effect of varying the interest acquired by way of a resulting trust because there was no discussion between the parties to that effect. Accordingly, the interests were shared in a 75:25 ratio. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘It is not enough to establish a common intention which is sufficient to found an implied or constructive trust of land that each of them happened at the same time to have been thinking on the same lines in his or her uncommunicated thoughts, while neither had any knowledge of the thinking of the other.’ |

| Dillon LJ |

9.3.5 Reliance and detriment

In addition to a common intention in respect of a beneficial interest in the family home, the claimant is required to show that he or she has relied on the understanding to his or her detriment or adjusted his or her position. This requires evidence of some action undertaken by the claimant, in reliance on the agreement, to be shown by the claimant. In other words, the claimant is required to show that he or she has acted on a common intention to such an extent that it would be inequitable or unconscionable to deny him or her an interest or enlarged interest in the property. In Burns v Burns we have seen that the claim failed where there was no express discussion between the parties as to the existence of a beneficial interest in the house and the claimant could not prove the existence of an implied intention as to a shared ownership. Lord Bridge affirmed this principle in Rosset:

JUDGMENT

| ‘[I]t will only be necessary for the partner asserting a claim to a beneficial interest against the party entitled to the legal estate to show that he or she has acted to his or her detriment or significantly altered his or her position in reliance on the agreement in order to give rise to a trust.’ |

9.3.6 Date and method of valuation of the interest

If the claimant has discharged the burden of proving a common intention as to a beneficial interest and that he or she has relied on that intention to his or her detriment, the next stage is to quantify the beneficial interest. If the parties have made an express declaration as to the size of the interest, the courts will give effect to this agreement except in cases of fraud or mistake. In the absence of such agreement the courts’ task will be to consider the entire course of dealings between the parties that is relevant to their ownership of the property in order to determine the extent of the beneficial interests. Financial contributions to the purchase price as well as a range of other factors (stated earlier) will be taken into account by the courts. The evidence that is considered by the courts concerning a variation of beneficial interest will be the same for joint and sole legal ownership cases, see Baroness Hale in Stack v Dowden:

JUDGMENT

| ‘The approach to quantification in cases where the home is conveyed into joint names should certainly be no stricter than the approach to quantification in cases where it has been conveyed into the name of one only. The questions in a joint names case are not simply What is the extent of the parties’ beneficial interests? but Did the parties intend their beneficial interests to be different from their legal interests? and If they did, in what way and to what extent? There are differences between sole and joint names cases when trying to divine the common intentions or understanding between the parties. |

| The burden will therefore be on the person seeking to show that the parties intend their beneficial interests to be different from their legal interests, and in what way. This is not a task to be lightly embarked upon. In family disputes, strong feelings are aroused when couples split up. These often lead the parties, honestly, but mistakenly, to reinterpret the past in self-exculpatory or vengeful terms.’ |

In the post-Rossei decision in Midland Bank v Cooke [1995] 4 All ER 562, the Court of Appeal took the bold decision to move away from the rigid principle laid down in Rosset and adopted a modified approach to the quantification issue. The approach was to the effect that where a party acquired an equitable interest in property by way of direct contributions to the purchase price of the property the court may take into consideration a broader view of the conduct of the parties in order to quantify their shares. The court was not bound to deal with the matter on the strict basis of the trust resulting from the cash contribution to the purchase price, and was free to attribute to the parties an intention to share the beneficial interest in some different proportions.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Midland Bank v Cooke [1995] 4 All ER 562 |