Constitution of an Express Trust

Constitution of an express trust

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

■ identify the essential tests in Milroy v Lord for the constitution of an express trust

■ appreciate that the law in this chapter involves gifts and the creation of trusts

■ distinguish between a perfect and an imperfect trust and understand the consequences of constitution

■ grasp the principle in Fletcher v Fletcher

■ understand and apply the maxims, ‘Equity will not assist a volunteer’ and ‘Equity will not perfect an imperfect trust’

4.1 Introduction

A settlor who wishes to create an express trust is required to adopt either of the following methods:

(a) a self-declaration of trust; or

(b) a transfer of property to the trustees, subject to a direction to hold upon trust for the beneficiaries.

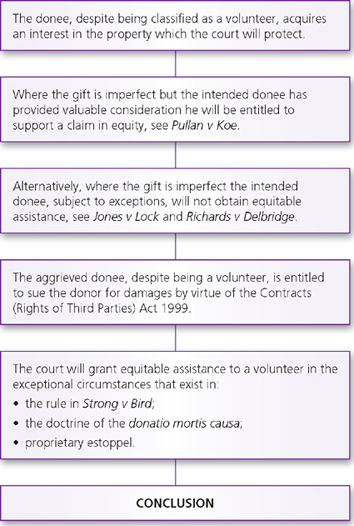

This is known as the rule in Milroy v Lord [1862] 31 LJ Ch 798, HC. The effect of the perfect creation of a trust is that the beneficiary, who may be a volunteer, may enforce the trust. However, if the trust is incompletely constituted, the transaction involving an intended trust operates as an agreement to create a trust. Subject to the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999, this agreement may be enforced by a person who has provided consideration.

Alternatively, a donor may make a perfect gift to the donee by transferring the legal and equitable interests directly to the desired donee. This involves a gift, as opposed to an intended trust. But a difficulty arises if the intended donor fails to transfer the legal title to the intended donee. The latter may be tempted to argue that the intended donor retains the legal title as an express trustee for the disappointed intended donee, and thus the imperfect transfer, by way of intended gift, constitutes the creation of an express trust. Such an argument, without any additional evidence, has been consistently rejected by the courts.

There are two maxims that summarise the approach of the courts: ‘Equity will not assist a volunteer’ and ‘Equity will not perfect an imperfect gift’.

4.2 The rule in Milroy v Lord [1862]

The principle laid down by Turner LJ in Milroy v Lord [1862] identifies the various modes of creating an express trust. Generally, there are two modes of constituting an express trust and the onus is on the settlor to execute one (or in exceptional circumstances both) of these modes for carrying out his intention.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Milroy v Lord [1862] 31 LJ Ch 798, HC |

| The settlor executed a deed purporting to transfer shares to Mr Lord on trust for Mr Milroy. The shares were only capable of being transferred by registration in the name of the transferee in the company’s books. The settlor failed to complete the transfer, although Mr Lord held a power of attorney as agent for the settlor. On the settlor’s death, Lord gave the share certificates to the settlor’s executors and the question arose whether the shares were held upon trust for the claimant. Held: There was no gift of the shares to the objects nor was there a transfer of the shares to the intended trustee. The settlor having failed to transfer the shares to the trustee, the court will not infer that he is a trustee for the claimant. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘[I]n order to render a voluntary settlement valid and effectual, the settlor must have done everything which, according to the nature of the property comprised in the settlement, was necessary to be done in order to transfer the property and render the settlement binding upon him. He may, of course, do this … if he transfers the property to a trustee for the purposes of the settlement, or declares that he himself holds it in trust for those purposes … but, in order to render the settlement binding, one or other of these modes must … be resorted to, for there is no equity in this court to perfect an imperfect gift. The cases go further to this extent, that if the settlement is intended to be effectuated by one of the modes to which I have referred, the court will not give effect to it by applying another of those modes. If it is intended to take effect by transfer, the court will not hold the intended transfer to operate as a declaration of trust, for then every imperfect instrument would be made effectual by being converted into a perfect trust.’ |

| Turner LJ |

On analysis, the court decided the following:

■ There was no gift of the shares to Mr Milroy.

■ The settlor did not have an intention to create a trust.

■ In order to create a trust or to transfer the property (legal title), the settlor or transferor is required to do everything expected of him in order to vest the property in the name of the intended transferee.

■ The settlor may transfer the property to the trustee subject to a valid declaration of trust.

■ The settlor may declare himself a trustee.

■ If the trust is intended to be created by one of these modes the court will not automatically adopt another mode of creating the trust.

These are the primary rules concerning the constitution of a trust.

4.2.1 Transfer and declaration mode

A settlor may wish to create a trust by transferring the property to another person (or persons) as trustee(s), subject to a valid declaration of trust. In this context the settlor must comply with two requirements, namely a transfer of the relevant property or interest to the trustees complemented with a declaration of the terms of the trust (see the ‘three certainties’ test above). If the settlor intends to create a trust by this method and declares the terms of the trust, but fails to transfer the property to the intended trustees, it is clear that no express trust is created. The ineffective transaction will amount to a conditional declaration of trust but without the condition (the transfer) being satisfied. For instance, S, a settlor, nominates T1 and T2 to hold 50,000 BT plc shares upon trust for A for life with remainder to B absolutely (the declaration of trust). In addition, S is required to transfer the property in the shares to T1 and T2. The declaration of trust on its own without the transfer is of no effect.

The formal requirements, if any, concerning the transfer of the legal title to property vary with the nature of the property involved. There are broadly two types of properties that exist — realty and personalty. In order to transfer the legal title to registered land the settlor is required to execute the prescribed transfer form and register the transfer in the names of the trustees at the appropriate Land Registry. The transfer of tangible moveable property requires the settlor to deliver the property to the trustees, accompanied by the appropriate intention to transfer; the transfer of the legal title to shares in a private company involves the execution of the appropriate transfer form and registration of the transfer in the company’s share register. The various requirements for the transfer of the most common forms of properties can be summarised as follows:

■ Legal estates and interests in land must be transferred by deed under s 52(1) of the Law of Property Act 1925.

■ Equitable interests in either land or personalty must be disposed of in writing: see s 53(1)(c) of the Law of Property Act 1925.

■ Choses in action (intangible personal property such as debts or intellectual property) may be assigned in law in writing in accordance with s 136 of the Law of Property Act 1925. As an alternative, an assignment may be executed in equity.

■ Tangible moveable property (chattels) may be transferred by delivery accompanied by clear and unequivocal intention that the transferor intends to transfer property to the recipient, or by deed of gift. In Re Cole [1964] Ch 175, a husband showed his wife the furniture in a house and said that it was all hers. The question in issue was whether a transfer of the legal title had taken place. Held: no transfer had taken place, as the words spoken were too loose to refect an intention to donate.

■ Shares in a private company will be transferred when the transfer procedure laid down in the Companies Act 2006 has been complied with.

4.2.2 Transfer of shares in a private company

The owner of the legal title to shares in a private company is the person whose details are registered in the company’s books. Thus, a new transferee acquires the legal title when he is registered with the company. The Companies Act 2006 outlines the procedure that is required to be followed in order to transfer shares in a private company. The transferor is required to execute a stock transfer form, issued under the Stock Transfer Act 1963, and send this, along with the share certificates, to the registered office of the company for registration. The company usually has an absolute discretion to decide whether to register the new applicant without giving reasons for its decision. In addition, the company deals only with the registered legal owner of the shares.

tutor tip

‘It is instructive to analyse the judgment of Turner LJ in Milroy v Lord [1862] 31 LJ Ch 798.’

In accordance with the Milroy v Lord [1862] principle, if the transferor has done everything required of him and the only things remaining to be done are to be performed by a third party, the transfer will be effective in equity. This is known as the ‘last act’ principle. The donor has completed the last act that may be achieved by him. This will be sufficient to transfer the equitable interest in the property to the donee. In these circumstances the donor who retains the legal title to the property holds it as a trustee for the donee. The type of trust is constructive and is thus created by operation of law. The effect is that dividends declared at any time after the transferor has completed his duties in respect of the transfer, and before the new owner is registered, will be held on trust for the new transferee. Likewise, votes attaching to the shares are required to be cast as trustee for the new owner. Whether the transferor has done everything required of him to transfer the shares is essentially a question of fact.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Rose [1952] Ch 499, CA |

| Mr Rose executed two transfers of shares on 30 March 1943. He died more than five years after executing the transfers, but less than five years (the claw-back period at this time) after the transfers were registered in the company’s books, on 30 June 1943. For estate duty purposes it was necessary to know when the donee had received the shares. Held: The shares were transferred on 30 March 1943. At this time the transferor had done everything in his power to transfer the shares, and all that remained was for the directors of the company to consent to the transfer and register the new owner. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘[I]f a document is apt and proper to transfer the property – is, in truth, the appropriate way in which the property must be transferred – then it does not seem to me to follow from the statement of Turner LJ [in Milroy v Lord [1862]] that, as a result, either during some limited period or otherwise, a trust may not arise, for the purpose of giving effect to the transfer. Whatever might be the position during the period between the execution of this document and the registration of the shares, the transfers were, on 30th June 1943, registered. After registration, the title of Mrs Rose was beyond doubt complete in every respect, and if Mr Rose had received a dividend between execution and registration and Mrs Rose had claimed to have that dividend handed to her, what would Mr Rose’s answer have been? It could no longer be that the purported gift was imperfect; it had been made perfect. I am not suggesting that the perfection was retroactive. |

| Lord Evershed MR |

JUDGMENT

| ‘The basic principle underlying all the cases is that equity will not come to the aid of a volunteer. Therefore, if a donee needs to get an order from a court of equity in order to complete his title, he will not get it. If, on the other hand, the donee has under his control everything necessary to constitute his title completely without any further assistance from the donor, the donee needs no assistance from equity and the gift is complete. It is on that principle, which is laid down in Re Rose, that in equity it is held that a gift is complete as soon as the settlor or donor has done everything that the donor has to do, that is to say, as soon as the donee has within his control all those things necessary to enable him, the donee, to complete his title.’ |

In contrast to the Re Rose [1952] principle, if the transferor has not done everything required of him, the transfer will not be effective in equity. This may be illustrated by Re Fry [1946].

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Fry [1946] Ch 312, HC |

| The donor of shares was domiciled in the USA, and needed the consent of the Treasury (under the Emergency Regulations (Defence (Finance) Regulations 1939)) to transfer shares in a British company. He sent the necessary forms to the company for registration of the new owner, save for Treasury approval. This he had applied for, but had not been granted at the time of his death. The question in issue was whether a transfer in equity had been made at the time of the donor’s death. Held: The shares had not passed to the donee at the time of the donor’s death, for he had not done everything required of him: he had not obtained Treasury consent. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘Had they, however, arrived at the position which entitled them, as against that company, to be put on the register of members? Had everything been done which was necessary to put the transferees into the position of the transferor? If these questions could be answered affirmatively, the transferees would have had more than an inchoate title; they would have had it in their own hands to require registration of the transfers. Having regard, however, to the Defence (Finance) Regulations 1939, it is impossible, in my judgment, to answer the questions other than in the negative. The requisite consent of the Treasury to the transactions had not been obtained, and, in the absence of it, the company was prohibited from registering the transfers. In my opinion, accordingly, it is not possible to hold that, at the date of the testator’s death, the transferees had either acquired a legal title to the shares in question, or the right, as against all other persons (including Liverpool Borax Ltd) to be clothed with such legal title.’ |

| Romer J |

The court decided that the donor had not done everything required of him to secure registration of the shares, despite his death after his application for Treasury approval was made. The logic of the Re Fry [1946] decision may be understood on the ground that the donor might have been required to furnish more information to the Treasury before consent was obtained. In any event, the company was not entitled legitimately to consider registering the new owner until Treasury consent was obtained. The court came to a similar decision on the facts of Milroy v Lord [1862] (see above).

In the case of Pennington v Waine [2002] All ER (D) 24, CA the Court of Appeal decided that where the donor had manifested an immediate and irrevocable intention to donate shares to another and had instructed her agent to execute the transfer, the donor will not be permitted to deny the interest acquired by the donee.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Pennington v Waine [2002] All ER (D) 24, CA |

| The donor, Ada, was the owner of a number of shares in a company and was also one of its directors. Under instructions from Ada, one of the company’s auditors, Mr Pennington, prepared a transfer form for 400 shares which was duly executed by Ada and sent to Mr Pennington. The transfer was in favour of Ada’s nephew, Harold, to secure his appointment as a director as a 51 per cent holder of shares. The form was placed on the company’s file. Mr Pennington assured Harold that he was appointed a director and nothing more was required to be done by him. No further action was taken in relation to the transfer. Ada died and by her will left her estate to others. The question in issue was whether a transfer in equity was made by Ada before her death in favour of Harold, or whether the shares passed to her heirs under her will. Held: A transfer to Harold in equity was made during Ada’s lifetime. Ada intended an immediate and irrevocable transfer in favour of Harold. The court considered that the test here was whether Ada had done everything required of her to secure the transfer, as distinct from whether she had done everything short of registration. The main ground for the decision was the fact that it would have been unconscionable for Ada and her heirs to deny the interest acquired by Harold. As an alternative ground the court decided that Ada and Mr Pennington were agents for Harold to submit the form to the company. The court also decided that the interim trust that arises, pending registration, is a constructive trust. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘There was a clear finding that Ada intended to make an immediate gift. It follows that it would also have been unconscionable for Ada to recall the gift. It follows that it would also have been unconscionable for her personal representatives to refuse to hand over the share transfer to Harold after her death. If Ada had procured the registration of Harold as the owner of the shares in the books of the company, the legal title to the shares would have passed to him. In these circumstances I can see no reason for holding that there was no valid equitable assignment to him without delivery of the transfer or shares to him. In those circumstances, in my judgment, delivery of the share transfer before her death was unnecessary so far as perfection of the gift was concerned. I would also decide this appeal in favour of the respondent on this further basis … the words used by Mr Pennington should be construed as meaning that Ada and, through her, Mr Pennington became agents for Harold for the purpose of submitting the share transfer to the Company.’ |

| Arden LJ |

It should be noted that the Pennington v Waine [2002] principle is distinct from the traditional Re Rose [1952] principle. In the former case, the court proceeded on the basis of ‘unconscionability’ on the part of the donor to deny that a transfer took place. This is a fairly broad concept and involves a question of law for the court to decide in its discretion, as opposed to the narrow Re Rose (1952) question of fact as to whether the donor had done everything required of him to effect the transfer. Unconscionability may involve a promise made by the donor, relied on by the donee to his detriment. In these circumstances the court will prevent the donor from denying the promise and reclaiming the property as his own.

In Pennington v Waine, Arden LJ decided that in certain circumstances the delivery of the share transfer form to the company could be dispensed with. This would be the case where it would be unconscionable for the donor to renege on his promise. In any event Arden LJ decided that the auditors could have been treated as the agent of the donor for the purpose of submitting the form to the company. In addition the status of the third party who decides on the registration of the legal title to the shares is required to be taken into account. If the third party has a formal role to play in deciding on the registration of the legal interest, then the constructive trust will be terminated on the date of the complete transfer of the legal title. But if the third party plays a more active role and has the power to refuse to register the transfer of the legal title the question arises as to whether the constructive trust will continue or be terminated. In Pennington v Waine the court in an obiter pronouncement decided that the constructive trust will continue to operate despite the refusal to register the new owner. On this basis it could be argued that the court has created another exception to the rule that ‘Equity will not perfect an imperfect gift.’

In addition to the transfer of the relevant property to the trustees, the settlor is required to declare the terms of a trust. In other words, the requirement here is that in order to constitute the trust the settlor must transfer the property to the trustees and, either before or after the transfer, declare the terms of the trust. A transfer of the property to the trustees unaccompanied by a declaration of trust by definition will not create an express trust. Such a transfer may create a resulting trust for the settlor. For example S, an intended settlor, purports to create an express trust of 10,000 BT plc shares by transferring the legal title to the shares to T1 and T2 as trustees, but failed to declare the terms of the trust. The intended beneficiary of the shares was his son, B, absolutely, but S failed to indicate the terms of the trust. Since T1 and T2 acquire the shares as trustees without a declaration of the terms of the trust, the intended express trust fails and a resulting trust for S will arise. Likewise, a declaration of trust of 10,000 BT plc shares in favour of B absolutely with the intention that T1 and T2 will acquire and hold the shares as trustees for B will fail if T1 and T2 did not acquire the relevant shares.

A declaration of trust involves a present, irrevocable intention to create a trust. This involves the ‘three certainties’ test: certainty of intention to create a trust, certainty of subject-matter and certainty of objects (see Chapter 3).

4.3 Self-declaration of trust

An alternative mode of creating an express trust is by way of a self-declaration. A settlor declares that he presently holds specific property on trust, indicating the interest, for a beneficiary. The settlor is the creator of the trust and the trustee. He simply retains the property as trustee for the relevant beneficiaries. Clear evidence is needed to convert the status of the original owner of the property to that of a trustee. This form of creating an express trust is as effective as the transfer and declaration mode. In the absence of specific statutory provisions to the contrary, no special form is required as long as the intention of the settlor is sufficiently clear to constitute himself a trustee, for ‘Equity looks at the intent rather than the form.’ Thus, the declaration of trust may be in writing or may be evidenced by conduct or may take the form of a verbal statement or a combination of each of these types of evidence: see Paul v Constance [1977] 1 WLR 527 (above); contrast Jones v Lock [1865] LR 1 Ch App 25 (above). What is required from the settlor is a firm commitment on his part to undertake the duties of trusteeship in respect of the relevant property for the benefit of the specified beneficiaries (see the ‘three certainties’ test, above). In this respect there is no obligation to inform the beneficiaries that a trust has been created in their favour. The effect of this mode of creation is to alter the status of the settlor from a beneficial owner to that of a trustee. For instance, S, the absolute owner of 50,000 shares in BP plc, declares that henceforth he holds the entire portfolio of shares upon trust for B, his son, absolutely. In these circumstances an express trust is created. S retains the legal title to the shares, but B acquires the entire equitable interest in the shares.

4.4 No self-declaration following imperfect transfer

The court will not automatically imply the self-declaration mode of creating a trust if there has been an imperfect gift or transfer of the property to the intended recipient. A gift is created when the donor transfers both legal and equitable interests to the donee. As distinct from a trust, the gift does not involve the separation of the legal and equitable interests. If, therefore, the donor intended to create a gift but fails to transfer the relevant property to the donee, the court will not assist the intended donee to order that the intended gift be perfected. Equally the intention to give is fundamentally different from an intention to create or declare a trust. Accordingly, an imperfect transfer will not be construed as a valid declaration of trust. This rule applies to imperfect gifts of property (see Jones v Lock [1865] above) as well as imperfect transfers to trustees, for ‘Equity will not perfect imperfect gifts.’ The reason for the rule is that, despite the transferor’s intention to benefit another by means of a transfer (whether on trust or not), the transferor ought not to be treated as a trustee if this does not accord with his intention: see Richards v Delbridge [1874] LR 18 Eq 11.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Richards v Delbridge [1874] LR 18 Eq 11 |

| A grandfather attempted to assign a lease of business premises to his grandson, R, by endorsing the lease and signing a memorandum: ‘This deed and all thereto I give to R from this time henceforth with all stock in trade.’ He gave the lease to R’s mother to hold on his behalf. On the death of the grandfather it was ascertained that his will made no reference to the business premises. The question in issue was whether the lease was acquired by the grandson, R, during the grandfather’s lifetime, or was transferred to the residuary beneficiaries under the grandfather’s will. Held: There was an imperfect gift inter vivos, as the assignment, not being under seal, was ineffectual to transfer the lease. Further, no trust had been created, as the grandfather did not declare himself a trustee of the lease for the grandson. The court will not construe an ineffectual transfer as a valid declaration of trust. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘[F]or a man to make himself a trustee there must be an expression of intention to become a trustee, whereas words of present gift show an intention to give over property to another, and not retain it in the donor’s own hands for any purpose, fiduciary or otherwise.’ |

| Sir George Jessel MR |

The principle has been summarised in a passage from F W Maitland’s Equity: A Course of Lectures (1909):

QUOTATION

‘I have a son called Thomas. I write a letter to him saying “I give you my Blackacre estate, my leasehold house in the High Street, the sum of £1,000 Consols standing in my name, the wine in my cellar.” This is ineffectual – I have given nothing – a letter will not convey freehold or leasehold land, it will not transfer Government stock, it will not pass the ownership in goods. Even if, instead of writing a letter, I had executed a deed of covenant – saying not I do convey Blackacre, I do assign the leasehold house and the wine, but I covenant to convey and assign – even this would not have been a perfect gift. It would be an imperfect gift, and being an imperfect gift the court will not regard it as a declaration of trust. I have made quite clear that I do not intend to make myself a trustee, I meant to give. The two intentions are very different – the giver means to get rid of his rights, the man who is intending to make himself a trustee intends to retain his rights but to come under an onerous obligation. The latter intention is far rarer than the former. Men often mean to give things to their kinfolk, they do not often mean to constitute themselves trustees. An imperfect gift is no declaration of trust. This is well illustrated by the case of Richards v Delbridge.’

4.5 The settlor may expressly adopt both modes of creation

The settlor may expressly manifest an intention to transfer the relevant property to third party trustees (transfer and declaration mode) and, prior to completing the transfer, to declare himself a trustee for the beneficiaries (self-declaration mode). In this event, the trust will be perfect, provided that the third party trustee acquires the property during the settlor’s lifetime. In other words, the self-declaration of trust is regarded as conditional on an effective transfer of the property to the third party trustee. This condition may only be satisfied during the lifetime of the settlor. The court has also decided that it is immaterial how the third party trustee acquires the property: see Re Ralli’s Will Trust [1964] Ch 288, HC.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Ralli’s Will Trust [1964] Ch 288, HC |

| In 1899, a testator died, leaving the residue of his estate upon trust for his wife for life with remainder to his two children, Helen and Irene, absolutely. In 1924, Helen covenanted in her marriage settlement and under clause 7 to settle all her ‘existing and after acquired property’ upon trusts which failed, and ultimately on trust for the children of Irene. The settlement declared that all the property comprised within the terms of the covenant will, under clause 8, ‘become subject in equity to the settlement hereby covenanted to be made’. Irene’s husband was appointed one of the trustees of this marriage settlement. In 1946, Irene’s husband was also appointed a trustee of the 1899 settlement. In 1956, Helen died and, in 1961, Helen and Irene’s mother died. The question in issue was whether Helen’s property from the 1899 settlement was held upon the trusts of Helen’s marriage settlement, or subject to Helen’s personal estate. Held: By virtue of the declaration in Helen’s settlement in 1924, Helen and, since her death, her personal representative (Irene’s husband), held her share of the 1899 settlement subject to the trusts of Helen’s settlement. This was the position even though the vesting of the property in Irene’s husband came to him in his other capacity as trustee of the 1899 settlement. The same conclusion could be reached by applying the rule in Strong v Bird [1874] LR 18 Eq 315 (see below). | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘In my judgment the circumstance that the plaintiff holds the fund because he was appointed a trustee of the will is irrelevant. He is at law the owner of the fund and the means by which he became so have no effect on the quality of his legal ownership. The question is: for whom, if any one, does he hold the fund in equity? In other words, who can successfully assert an equity against him disentitling him to stand on his legal right? It seems to me to be indisputable that Helen, if she were alive, could not do so, for she has solemnly covenanted under sea to assign the fund to the plaintiff and the defendants can stand in no better position.’ |

| Buckley J |

In this case it is worth noting the fortuitous event in 1946 when Irene’s husband was appointed a trustee of the 1899 settlement. This meant that the third party trustee acquired the trust property, and since it was during Helen’s lifetime, the trust became perfect.

4.6 Multiple trustees including the settlor

In the case of Choithram International v Pagarani [2001] 1 WLR 1, PC, the Privy Council decided that where the settlor appoints multiple trustees, including himself, and declares a present, unconditional and irrevocable intention to create a trust for specific persons, a failure to transfer the property to the nominated trustees is not fatal, for his (settlor’s) retention of the property will be treated as a trustee. Trusteeship for these purposes is treated as a joint office so that the acquisition of the property by one trustee is equivalent to its acquisition by all the trustees. For example, S nominates himself and T1 and T2 as trustees of property and specifies the terms. If S manifests an irrevocable and unconditional intention to create a trust, his failure to transfer the property to T1 and T2 is not fatal because S retains the property as a trustee. His retention of the property as one of the trustees is equivalent to all the trustees acquiring a right to acquire the property. Thus the trust is perfect.

CASE EXAMPLE

JUDGMENT

| ‘The foundation has no legal existence apart from the trust declared by the foundation trust deed. Therefore the words I give to the foundation can only mean I give to the trustees of the foundation trust deed to be held by them on the trusts of the foundation trust deed. Although the words are apparently words of outright gift they are essentially words of gift on trust … What is the position here where the trust property is vested in one of the body of trustees, viz TCP? In their Lordships’ view there should be no question. TCP has, in the most solemn circumstances, declared that he is giving (and later that he has given) property to a trust which he himself has established and of which he has appointed himself to be a trustee. All of this occurs at one composite transaction taking place on 17 February. There can in principle be no distinction between the case where the donor declares himself to be sole trustee for a donee or a purpose and the case where he declares himself to be one of the trustees for that donee or purpose. In both cases his conscience is affected and it would be unconscionable and contrary to the principles of equity to allow such a donor to resile from his gift.’ |

| Lord Browne-Wilkinson |

4.7 No trust of future property

It is not possible to create an express trust of property that does not exist or property that may or may not be acquired by the settlor simply because there is no property that is capable of being subject to an order of the court. Such property is referred to by a variety of names but the principle remains the same. Examples of terms used are ‘future’ or ‘after-acquired’ property or an ‘expectancy’ or a ‘spes’ (or hope of acquiring property). Thus, it is not possible to create a trust of lottery winnings in the future.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Ellenborough [1903] 1 Ch 697, HC |

| An intended beneficiary under a will voluntarily covenanted to transfer her inheritance to another upon trusts as declared. Before the testator had died the intended beneficiary (covenantor) changed her mind. The covenantee brought an action claiming that the covenantor was under a duty to transfer the relevant property. Held: No trust of the covenant had been created, because the property was not owned by the covenantor at the time of the covenant. In addition, the covenantee could not bring an action to enforce the agreement for he had not provided consideration. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘The question is whether a volunteer can enforce a contract made by deed to dispose of an expectancy. It cannot be and is not disputed that if the deed had been for value the trustees could have enforced it … Future property, possibilities, and expectancies are all assignable in equity for value: Tailby v Official Receiver [1888] 13 App Cas 523. But when the assurance is not for value, a court of equity will not assist a volunteer.’ |

| Buckley J |

It should be noted that although a trust cannot be created in respect of future property, a contract is capable of being created in respect of such property.

4.8 Trusts of choses in action

A chose in action is a right to intangible personal property such as a right to dividends attaching to shares, intellectual property and the creditor’s right to have a loan repaid by the debtor. A trust is capable of being created in respect of any type of existing property, including a chose in action. The chose may be assigned to the trustees in accordance with the intention of the settlor.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Don King Productions Inc v Warren [1999] 2 All ER 218, CA |

| K and W (two well-known boxing promoters) entered into partnership agreements in which W purported to assign the benefit of promotion and management agreements to the partnership. However, several of the contracts contained express prohibitions against assignment. The question in issue was whether a trust of the benefit of the agreements (choses in action) was created. Held: The benefit of promotion and management agreements was capable of being the subject-matter of a trust in accordance with the intention of the parties. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘[I]n principle, I can see no objection to a party to contracts involving skill and confidence or containing non-assignment provisions from becoming trustee of the benefit of being the contracting party as well as the benefit of the rights conferred. I can see no reason why the law should limit the parties’ freedom of contract to creating trusts of the fruits of such contracts received by the assignor or to creating an accounting relationship between the parties in respect of the fruits.’ |

| Lightman |

Similarly, the court may construe the subject-matter of a covenant as creating a chose in action, namely the benefit of the covenant. This intangible property right may be transferred to the trustees on trust for the relevant beneficiaries. What is needed to assign such a right or chose is a clear intention on the part of the assignor to dispose of the chose to the transferee. Accordingly, A may execute a covenant with B to transfer 10,000 to B upon trust for C. If the subject-matter of the trust is treated as the cash, namely 10,000, it becomes a question of fact as to whether the sum has been transferred to B. If we assume that A did not transfer the sum to B it is still possible that the trust may be treated as perfect. The court may construe the trust property as the ‘benefit of the covenant’ or the ‘right to the cash’, i.e. a chose in action. This chose may be transferred by operation of law in accordance with the intention of the parties. Therefore, in a sense the trust is perfect in that B has the trust property even though A did not transfer 10,000 in cash to B. B having acquired the right to the cash is entitled to claim the cash from A. This difficult principle is known as the rule in Fletcher v Fletcher [1844] 4 Hare 67.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Fletcher v Fletcher [1844] 4 Hare 67 |

| The settlor, Ellis Fletcher, covenanted (for himself, his heirs, executors and administrators) with trustees (their heirs, executors, administrators and assigns) to the effect that if either or both of his natural issue (illegitimate children), Jacob and John, survived him and attained the age of 21, Ellis’s executors would pay to the covenantees (or heirs etc.) £60,000 within 12 months of his death, to be held on trust for the relevant natural issue. In the circumstances, Jacob alone survived the settlor and attained the age of 21. The surviving trustees (covenantees) declined to act in respect of the trust of the covenant, unless the court ordered otherwise. Jacob brought an action directly against the executors, claiming that he become solely entitled in equity to the property. Held: A trust of the covenant was created in favour of Jacob, the claimant, who was entitled to enforce it as a beneficiary. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘[W]here the relation of trustee and cestui que trust is constituted, as where property is transferred from the author of the trust into the name of a trustee, so that he has lost all power of disposition over it, and the transaction is complete as regards him, the trustee, having accepted the trust, cannot say he holds it, except for the purposes of the trust, if it is not already perfect. This covenant, however, is already perfect. The covenantor is liable at law, and the court is not called upon to do any act to perfect it.’ |

| Wigram VC |

On analysis, in Fletcher v Fletcher [1844], the court decided that:

(a) On construction of the terms of the covenant, the intended trust property was the ‘benefit of the covenant’ or a right to the cash sum, i.e. a chose in action, and not the cash sum of 60,000.

(b) Since the sum had existed in Ellis Fletcher’s estate at the time of the covenant, this chose in action was transferred to the covenantees, trustees, on the date of the creation of the covenant.

(c) The covenantees therefore became trustees, subject to the achievement of the stipulated conditions, surviving the settlor and attaining the age of 21.

(d) Since Jacob satisfied these conditions he became a beneficiary unconditionally and was therefore entitled to protect his interest.

It is questionable who had the ‘benefit of the covenant’. Was it Ellis Fletcher or the covenantees, trustees? Did Ellis Fletcher have the benefit of the covenant? He was the covenantor. He (or his estate) was under a duty to transfer the sum to the covenantees, trustees. He (or his estate) therefore had the burden of transferring the sum to the covenantees, trustees. It is true that Ellis Fletcher had the cash in his estate at the time of the covenant, but this did not derive from the covenant. This sum existed independently of the covenant.

Alternatively, it could be argued that the covenantees, trustees had the ‘benefit of the covenant’ as covenantees. They were nominated as the recipients of the sum of 60,000, albeit in a representative capacity. In other words, between the two parties to a voluntary covenant – the covenantor and the covenantees – only the covenantees may be treated as acquiring the ‘benefit of the covenant’. If this is the true position, then only the covenantees may create a trust of this chose or benefit: i.e. only the covenantees may become the settlors of the chose in action. On the facts of Fletcher v Fletcher [1844], this was clearly not the intention of the covenantees, trustees.

A separate analysis of the Fletcher v Fletcher [1844] rule which is consistent with the Milroy v Lord [1862] principle is to identify the trust property as the cash sum of 60,000, and not the ‘benefit of the covenant’ or the chose in action. The issue then is whether the covenantees, trustees, acquired, or were entitled to acquire, the cash sum and, if so, when. It could be argued that the terms of the covenant were unique and imposed a positive duty, not on Ellis Fletcher, but his personal representatives to transfer 60,000 to the covenantees as trustees for Jacob. Under the covenant Ellis Fletcher merely had a duty to retain the cash sum in his estate at the time of his death. If he had done this at the time of his death then Ellis Fletcher would have done everything in his power, barring his death, to perfect the trust under the Re Rose (1952) principle. He was merely required to die (an issue outside his control), leaving the cash sum in his estate. This he had done. At this point a positive duty would be imposed on Ellis Fletcher’s personal representatives to transfer the property to the covenantees, trustees.

4.8.1 Fletcher restricted to debts enforceable at law

Owing to the difficulties posed by the Fletcher v Fletcher [1844] principle and the opportunities for intended beneficiaries under an imperfect trust, it is not surprising that the principle has been restricted by the courts to one type of chose in action, namely debts enforceable at law. A debt enforceable at law involves a legal obligation to pay a quantified amount of money. It does not concern an obligation to transfer shares or paintings. In addition the obligation involves existing, and not future, property. This restriction was imposed in an obiter pronouncement in Re Cook’s Settlement Trust [1965] Ch 902, HC.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Cook’s Settlement Trust [1965] Ch 902, HC |

| A number of valuable paintings were gifted by his father to Sir Francis Cook, who covenanted with trustees to the effect that if any of the paintings was sold during his lifetime, the net proceeds of sale were required to be settled on trust for stated beneficiaries. Sir Francis gave one of the paintings to his wife who wanted to sell it. The question in issue was whether the covenant may be enforced as an agreement to create a trust or as a trust. Held: (a) The parties to the agreement were volunteers who could not enforce the covenant. (b) The intended trust was imperfect for the subject-matter concerned future property, i.e. the proceeds of sale in the future. For this reason the Fletcher [1844] principle was not applicable. In any event the Fletcher principle was applicable to debts enforceable at law. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘The covenant with which I am concerned did not, in my opinion, create a debt enforceable at law, that is to say, a property right, which, although to bear fruit only in the future and on a contingency, was capable of being made the subject of an immediate trust, as was held to be the case in Fletcher v Fletcher … this covenant on its true construction is, in my opinion, an executory contract to settle a particular fund or particular funds of money which at the date of the covenant did not exist and which might never come into existence. It is analogous to a covenant to settle an expectation or to settle after acquired property.’ |

| Buckley J |

KEY FACTS

| Constitution of express trusts |

| Rule in Milroy v Lord [1862] (a) self-declaration of trusts (b) transfer to trustees and declaration | Settlor is the trustee (‘three certainties’ test) Re Kayford [1975]; Paul v Constance [1977] Vesting of property in the hands of the trustees accompanied by a valid declaration of trust |

| Transfer of the legal title – nature of the property | Land – registration under the LRA 1925 Chattels – deed of gift or delivery Re Cole [1964] Shares in a private company – execution of a stock transfer form and registration in the company’s share register choses in action – assignment at law under s 136 LPA 1925 |

| Transfer of the equitable interest Whether the transferor has done everything required of him to effect the transfer | Writing under s 53(1)(c) of the LPA 1925 Re Rose [1952]; Mascall v Mascall [1984]; Pennington v Waine [2002] |

| Where there are multiple trustees nominated by the settlor (including the settlor) and the latter has manifested an irrevocable intention to create a trust, the trust is valid even though the other named trustees have not acquired the property | Choithram v Pagarani [2001] |

| An imperfect transfer to the trustees will not automatically be treated as a valid declaration of trust | Richards v Delbridge [1874]; Jones v Lock [1865] |

| A settlor may expressly declare himself a trustee pending a transfer to the third party trustees. If the transfer takes place during the lifetime of the settlor the trust will be perfect | Re Ralli [1964] |

| The benefit of a covenant (chose in action of a debt) may be the subject-matter of a trust | Fletcher v Fletcher [1844] |

4.9 Consequences of a perfect trust

sui juris

A person who is under no disability, such as mental illness, affecting his power to own or transfer property.