Variation of a Trust and Setting a Trust Aside

Chapter 10

Variation of a Trust and Setting a Trust Aside

Chapter Contents

Circumstances When a Trust Can Be Varied Today

As You Read

Look out for the following issues:

the common law and statutory authorities which permit a trust to be varied;

the common law and statutory authorities which permit a trust to be varied;

the Variation of Trusts Act 1958, which is the main statutory authority, which enables the court to approve proposed variations of trust in certain situations; and

the Variation of Trusts Act 1958, which is the main statutory authority, which enables the court to approve proposed variations of trust in certain situations; and

when a trust may be set aside if it has been set up to defeat or defraud a settlor’s creditors.

when a trust may be set aside if it has been set up to defeat or defraud a settlor’s creditors.

Variation of a Trust

Background

It has been shown that there are a number of requirements to establish a valid trust. To set up a workable trust, the settlor must:

[a] fulfil any formality requirements if the type of property to be left on trust requires it1 (for example, a trust of land must be evidenced in writing and signed by someone able to declare the trust under s 53(1)(b) of the Law of Property Act 1925);

[b] comply with the three certainties: intention, subject matter and object;2

[c] comply with the beneficiary principle;3

[d] adhere to the rules against perpetuity;4 and

[e] constitute the trust.5

These rules generally exist to provide some protection for the trustee. The first four criteria — relating to declaring the trust — ensure that it must be absolutely clear that a trust has been created, spell out categorically what it is that the trustee is supposed to administer and in whose favour the trustee must manage the trust. Constituting the trust ensures that the trustee can manage the trust property by transferring the legal title in the property to him.

If, however, the settlor has jumped through all of the hoops required in creating a trust, it might be thought that varying the trust would be very strange to him as he will have spent a lot of time and trouble setting up the trust and perhaps would not want those arrangements disturbed by their being subsequently altered.

The basic rule here is that, once established, it is not possible to vary a trust. This was explained by Lord Evershed MR in Re Downshire Settled Estates:6:

The general rule … is that the court will give effect, as it requires the trustees themselves to do, to the intentions of a settlor as expressed in the trust instrument, and has not arrogated to itself any overriding power to disregard or rewrite the trusts.7

Yet equity has always permitted a trust to be varied in certain circumstances. Originally, equity’s jurisdiction to alter a trust was used to deal with property or the management of it for children or mentally disabled individuals.8

Trusts nowadays tend to be established as a method of saving tax. Each year, however, the Finance Act following the government’s Budget makes changes to the taxation system. Consequently, an original tax-efficient trust that may have been established may have become less tax efficient than it was at the time the trust was set up. The beneficiaries might, therefore, wish to vary the trust to minimise their liability to tax.

APPLYING THE LAW APPLYING THE LAW |

Varying a trust to avoid tax can result in large savings to the beneficiaries. Such a variation occurred in Re Norfolk’s Will Trusts; Norfolk v Howard9 in which the sixteenth Duke of Norfolk successfully applied to the High Court to vary the trusts set up by his father. As a result of the court approving the variation, the beneficiaries of the revised trust enjoyed an additional £550,000 that would otherwise have been payable in taxation.

The court does not act as a slave to HM Revenue & Customs and is not predisposed to prevent variations of trust occurring just because their purpose is to avoid tax. In fact, the contrary is true, according to Lord Evershed MR in Re Downshire Settled Estates, in that it is:

not an objection to the sanction by the court of any proposed scheme in relation to trust property that its object or effect is or may be to reduce liability for tax.10

It is important to note, however, that a trust may only be varied when permitted and saving tax does not have to be a prerequisite to a successful application to vary a trust. The crucial issue is when it is permitted to vary a trust.

Circumstances When a Trust Can Be Varied Today

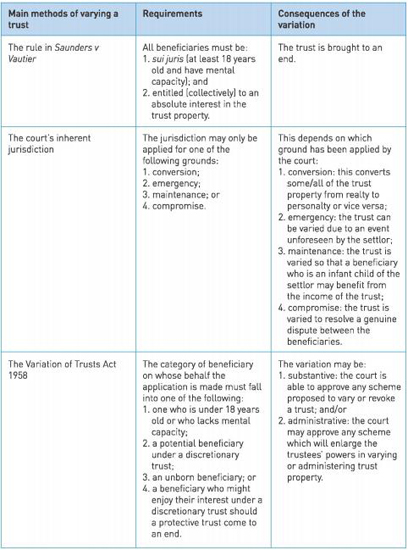

A trust may be varied using one of three main methods. Before the intricacies of each method are examined, a table setting out the main parts of those methods is set out in Figure 10.1. These methods only apply if there is not an express power to vary the trust contained in the

Each of these methods must be examined in turn.

Varying a trust with the consent of all adult beneficiaries

If they act together, all adult beneficiaries are entitled to vary the trust provided that they all collectively enjoy an absolute interest in the trust property. They must all enjoy mental capacity. The result of a group of adult beneficiaries owning the entire equitable interest collectively is that the trustees hold the trust property on a bare trust. The ability of the beneficiaries to vary the trust comes from the decision in Saunders v Vautier,11 which gives rise to what is sometimes known as ‘the rule in Saunders v Vautier’.

Here, a testator left shares in the East India Company worth £2,000 on trust for the benefit of his great-nephew, Daniel Wright Vautier. There was a direction in the testator’s will that the income from the shares had to be accumulated (reinvested) into the capital until Daniel reached 25 years old. At that point, the capital of the shares, together with all of the accumulated income, was to be transferred to him. The testator died when Daniel was still a child.

In March 1841, Daniel attained 21 years old, then the age of majority. He applied to the Court of Chancery to have the whole fund (both the value of the shares and the accumulated income) transferred to him, four years earlier than that envisaged by the creation of the trust.

Lord Langdale MR agreed that the whole fund should be transferred to Daniel. He said that:

the legatee, if he has an absolute indefeasible interest in the legacy, is not bound to wait until the expiration of that period, but may require payment the moment he is competent to give a valid discharge.12

The moment when Daniel could give a valid discharge — or receipt — for the money was when he reached the age of majority.

The decision in the case turned on the fact that Daniel had an absolute interest in the trust property. The other residuary legatees argued that he had a contingent interest, an interest which he could only enjoy provided he reached the age of 25. The court rejected this argument. It seems it was on the basis that the testator had merely directed the income to be accu-mulated. He had actually given Daniel a vested interest in the shares but simply directed the income to be accumulated for his maintenance.

The decision in the case shows that beneficiaries who enjoy an absolute vested interest in the trust property may call for it to be transferred to them. In a sense, it is an example of a trust being varied but it is a rough-and-ready variation as it simply brings the trust to an end. As the trust was, in any event, a bare trust only, it is not a particularly significant step for the adult beneficiary to call for the trust property to be transferred to themselves.

The principle from Saunders v Vautier still stands but now applies to beneficiaries at a younger age. As a result of s 1 of the Family Law Reform Act 1969 being enacted, the age of majority was lowered in English law to 18 years of age from 21. That means that if a beneficiary reaches the age of 18 and enjoys an absolute vested interest in trust property, he can compel the trustee to transfer the trust property to himself. That transfer will mark the end of the trust. The ratio decidendi of the case also applies where there are a number of adult beneficiaries who collectively all enjoy the equitable interest in the trust property, provided they all have mental capacity.

Varying a trust under the court’s inherent jurisdiction

As You Read

This area is concerned with when the court has an inherent right to sanction a variation of trust on behalf of infants, those unborn or mentally incapable beneficiaries as those categories of people cannot give their own consent. Beneficiaries who are 18 years or over and mentally capable must continue to give their own consent and the court cannot override such beneficiaries’ wishes.

As will be seen, the extent of the court’s inherent jurisdiction to vary a trust is very limited and it could be questioned whether such a jurisdiction even exists at all.

The difficulty with the rule in Saunders vVautier is that it is of very limited application. It only applies to beneficiaries who:

are all adults and who are mentally capable (‘sui juris’);

are all adults and who are mentally capable (‘sui juris’);

all have an absolute, vested interest in the trust property; and

all have an absolute, vested interest in the trust property; and

have no other desire than to end the trust by transferring the legal interest in the trust property to themselves.

have no other desire than to end the trust by transferring the legal interest in the trust property to themselves.

Before the decision of the House of Lords in Chapman v Chapman,13 the courts also thought that they enjoyed a much wider discretion to vary a trust if asked to do so, as part of an inherent jurisdiction that the Court of Chancery originally enjoyed. Quite how wide their discretion lay depended on the views of the individual judges.

The relatively wide view of the Court of Appeal

In Re Downshire Settled Estates, Lord Evershed MR, with whom Romer LJ agreed, whilst not wishing to impose ‘undue fetters’14 on the court’s discretion, thought that the court actually enjoyed only a limited inherent discretion (as a successor to the Court of Chancery) to vary a trust. This limited discretion enjoyed by the court was to enable the court to give the trustees such addi-tional administrative powers as were necessary for the trustees to deal with the trust property if an ‘emergency’ arose. Such administrative powers had to be used for the benefit of ‘everyone interested’15 under the trust. An ‘emergency’ was defined to mean something that the settlor had not planned for when setting up the trust as opposed to involving notions of extreme urgency in the need to vary the trust. It also had to be for everyone’s benefit that the court granted the trustees additional administrative powers.

Lord Evershed MR quoted from the example given in the judgment of a different Romer LJ in Re New16 of the emergency situation under consideration. In that case, Romer LJ gave the example of a testator creating a trust in his will giving a direction to his trustees to sell some of the trust property at a particular point in time. When that time arrived, the market for the property had fallen, which meant that complying with the testator’s wishes in selling the property would create a loss to the estate. He said that in such a situation, the court would authorise a power to be given to the trustees to postpone the sale of the property until a later date. Such an event was an ‘emergency’ because it was unforeseen by the settlor when establishing the trust. The court was able to intervene to grant further administrative powers to the trustee.

In Re Downshire Settled Estates, Lord Evershed MR said a wider exception existed where the beneficiaries were either infants or mentally incapable. In those situations, the court was able to step in more generally to vary the trust. This was because the beneficiaries were not adults and not, therefore, in a position to act together, so as to enjoy the benefit of the rule in Saunders v Vautier. In acting in this situation, the court would be permitting the variation of the interests of the infants or mentally incapable beneficiaries. Those who were adults and mentally capable would need to give their own consent. This was known as ‘compromising’ the claims of the infant or mentally incapable beneficiaries, which really meant the court was acceding to a bargain that the sui juris beneficiaries had put forward. The word ‘compromise’ was to be given a wide meaning and was not to be limited to settling disputed claims.

The third judge in the case, Denning LJ, took a typically more robust position as to when the court should be able to exercise its inherent jurisdiction. He believed that the Court of Chancery had enjoyed a jurisdiction to sanction any acts done by trustees for the benefit of either infant or mentally incapable beneficiaries provided the court was satisfied that the variation was indeed for their benefit. Given that, acting together, beneficiaries who were sui juris could agree to a variation of trust themselves, Denning LJ’s views would have given the court a wide discretion to vary a trust in the case of infant or mentally incapable beneficiaries: the variation simply had to be for their benefit.

The narrower view of the House of Lords

The decision of the House of Lords in Chapman v Chapman (handed down within 16 months of the Court of Appeal’s decision in Re Downshire Settled Estates) placed strict limits on when a court could sanction the variation of a trust.

The facts concerned trusts established by Sir Robert and Lady Chapman for the benefit of their grandchildren. The trusts contained substantial sums of money for their benefit, with the effect that upon the settlors‘ deaths, a large sum (approximately £30,000) would be due to the Inland Revenue in the form of death duties. A scheme was proposed by the adult beneficiaries and trustees under which money would be taken from the established trusts and transferred to new trusts which would omit the provisions that gave rise to the tax being charged. The court’s consent was needed on behalf of the infant beneficiaries.

The House of Lords refused to approve the scheme on the basis that the court enjoyed no jurisdiction to give authority to such a variation of trust on behalf of the infant beneficiaries. The House of Lords adopted a firm stance against the court having any jurisdiction to vary a trust and thought that any such ability the court did enjoy was by way of exception rather than the norm.

The most detailed opinion was delivered by Lord Morton. He believed that previous case law of when the court had sanctioned variations of trust under its inherent jurisdiction could be grouped together under four heads:

[a] the ‘conversion’ jurisdiction;

[b] the ‘emergency’ jurisdiction;

[c] the maintenance jurisdiction; and

[d] the compromise jurisdiction.

The ‘conversion’ jurisdiction

This jurisdiction concerns the ability of the court to sanction a variation of trust in converting the nature of the property to which an infant or mentally incapable beneficiary is entitled. For example, a trust might wish to be varied so as to allow the infant’s interest in personalty to be invested in realty.17 Lord Morton believed that the court had always enjoyed an inherent jurisdiction to sanction such variations of trust. Such a jurisdiction was uncontroversial and would continue to be permitted.

The ‘emergency’ jurisdiction

Lord Morton believed that the court did enjoy a jurisdiction to sanction a trust being varied on behalf of those beneficiaries who were incapable of giving their own consent but such jurisdiction was of an extremely limited nature.

He quoted with approval the comments delivered by Romer LJ in Re New. The facts of that case concerned three separate trusts set up by shareholders in the Wollaton Colliery Company Ltd for the benefit of their children. The originally priced £100 shares left on the trusts had increased substantially in value to be worth £175 each. The shareholders of the company wanted to reorganise the company so that, effectively, each of the shares would be split into smaller shares. Shares worth a smaller amount could be bought and sold more easily as they would appeal to more investors. This would be achieved by the creation of a new company and the exchange of the original shares for shares in the new company. All of the shareholders of the company were keen for the scheme to go ahead, as were the trustees of the trusts. The problem was that some of the beneficiaries were not s ui juris and could not give their own consent to the variation of the trust. The court’s consent would be needed if the scheme was to go ahead.

APPLYING THE LAW APPLYING THE LAW |

Even today, certain companies‘ share prices increase dramatically beyond initial expecta-tions when the shares are first issued. The best example nowadays is probably that of Apple, whose shares initially traded at $22 but were worth over $600 each in early 2012.

In giving the judgment of the Court of Appeal, Romer LJ began by stating the general rule that the court has no jurisdiction to sanction any acts that the trustees wish to undertake which are not permitted by the terms of the trust. However, the court could sanction acts which had to be done by trustees in an ‘emergency’. An emergency was one which:

may reasonably be supposed to be one not foreseen or anticipated by the author of the trust, where the trustees are embarrassed by the emergency that has arisen and the duty cast upon them to do what is best for the estate, and the consent of all the beneficiaries cannot be obtained by reason of some of them not being sui juris or in existence …18

But the court would exercise its jurisdiction with ‘great caution’19 and

will not be justified in sanctioning every act desired by trustees and beneficiaries merely because it may appear beneficial to the estate … each case brought before the Court must be considered and dealt with according to its special circumstances.20

On the facts of the case, the proposed variations of each of the three trusts were permitted.

The decision of the Court of Appeal in Re Tollemache21 (in which Romer LJ again sat) just two years later set out limits of the emergency jurisdiction considered in Re New. Cozens-Hardy LJ described the decision in Re New as ‘the high-water mark of the exercise by the court of its extraordinary jurisdiction in relation to trusts’.22 Vaughan Williams LJ said that the court could only exercise its emergency jurisdiction to sanction a variation of trust if the emergency had to be dealt with ‘at once’.23

Lord Morton approved the comments of Romer LJ in Re New and the decision of the Court of Appeal in Re Tollemache as setting limits on the extent of the emergency jurisdiction. He summed up24 the jurisdiction as being there to ‘salvage’ trust property rather than do anything more proactive in the management of a trust.

The maintenance jurisdiction

This concerns the court’s ability to provide for children of the settlor. If a trust has been created which directs the income from it to be accumulated into the capital, prima facie, any children of the settlor would not be provided for on a day-to-day basis from the trust fund. The court has assumed that such a settlor would not have desired their children to be destitute and so has sanctioned the maintenance of such children.

Lord Morton regarded this ability to provide maintenance as a limited exception to the principle that the court had no jurisdiction to vary a trust. He quoted, with approval, Farwell J in Re Walker:25

I decline to accept any suggestion that the court has an inherent jurisdiction to alter a man’s will because it thinks it beneficial. It seems to me that is quite impossible.

Lord Morton believed Farwell J’s words were ‘equally true in the case of a settlement’.26

The facts of Re Walker concerned a trust established by Sir James Walker in his will of 1882 in which he left a considerable amount of land in Yorkshire on trust for the life of his son and, in turn, each of his sons. The trust contained a direction that £500 per year should be used from the income of the land to maintain any infant beneficiary. This maintenance was to include the upkeep of the house, Sand Hutton Hall, in which each beneficiary was directed to reside. An infant beneficiary, the great-grandson of Sir James, brought an action to vary the trust so that £4,000 might be used from the income each year for his maintenance and education, arguing that £500 per year was insufficient to maintain such a vast residence as Sand Hutton Hall.

Although wary of altering Sir James’ will, Farwell J sanctioned the variation of the trust in this manner. The judge found that the will contained a ‘paramount intention’27 by Sir James that Sand Hutton Hall should be kept in good repair, but he had made no specific provision for maintaining the house. In addition, he found the will contained a separate allowance of £500 per year for an infant beneficiary’s personal maintenance, which could take the form of meeting the costs of the child’s education. As Sir James had not forbidden a larger sum being spent on the maintenance and education of an infant beneficiary when more was needed than he had provided for in the trust, the trust could be varied to reflect Sir James‘ intentions that the property and the infant beneficiary both be maintained appropriately.

Re Walker is a good illustration of the court exercising a jurisdiction to sanction the variation of a trust to maintain an infant beneficiary by providing a suitable place for him to live. But as the comments of Farwell J make clear, as supported by Lord Morton in Chapman v Chapman, the court’s ability to vary the trust in this manner is clearly limited. The court must find an intention of the settlor to maintain a beneficiary and, in that sense, the court is not really approving a dramatic variation of a trust. In Re Walker, the settlor had always made provision for the infant beneficiary; all that was in issue was the appropriate amount that should be apportioned to this maintenance.

Even if a settlor has made no specific provision to maintain an infant beneficiary in the trust, the jurisdiction here appears to be limited to trusts concerning the settlor’s family, according to Pearson J in Re Collins.28 It may be that this jurisdiction could be extended slightly although the prospects of that occurring are small. It is perhaps only a small step for the court to sanction the maintenance of a person that the settlor would have naturally maintained during their life.

ANALYSING THE LAW ANALYSING THE LAW |

Does Re Collins reflect modern day lives? Should the court’s jurisdiction be extended to maintain other children for whom, perhaps, the settlor has assumed responsibility during his life? For example, if the settlor has made his infant godchild a beneficiary under a trust in his will, should the court nowadays be permitted to vary that trust to maintain the child?

The compromise jurisdiction

Lord Morton acknowledged that there were ‘many’29 reported cases in which the Court of Chancery and the High Court had approved compromises in relation to infants or unborn children. This did not mean that the court enjoyed an unlimited jurisdiction to vary a trust, however, by compromising beneficiaries’ claims to the trust. Trusts which were potentially to benefit infants and unborn children were, at that stage, ‘ex hypothesi, still in doubt and unascertained’30 because their interests had not yet been ascertained. The problem arose when interests were ascertained:

If, however, there is no doubt as to the beneficial interests, the court is, to my mind, exceeding its jurisdiction if it sanctions a scheme for their alteration, whether the scheme is called a ‘compromise in the broader sense’ or an ‘arrangement’ or is given any other name.31

Lord Morton thought that the views of the members of the Court of Appeal on the ability of the court to approve compromises in Re Downshire Settled Estates were too wide. The court did not have any jurisdiction to approve contrived ‘compromises’ between beneficiaries.

Lord Simonds LC made it clear in his speech that the court’s jurisdiction to sanction a compromise meant that the court could only make a decision in the event of a genuine dispute of a beneficiary’s rights. A practice had grown up in the first half of the twentieth century in which High Court judges would, in chambers, approve variations to trusts on behalf of infants or unborn children. Disputes had often been manufactured by the parties to the trust as this was the only way to obtain the court’s sanction to a variation of the original trust. Lord Simonds LC disapproved of such a procedure as frequently it had simply been assumed that the High Court had jurisdiction to make such orders varying beneficial interests in this manner. As such hearings were in chambers, they were not subject to the transparency and scrutiny that decisions in open court enjoy. Lord Simonds LC believed that the only time the compromise jurisdiction should be used by the courts was in the case of a real dispute over beneficial rights and where the court’s consent was sought on behalf of infants or unborn children. In doing so, Lord Simonds LC disagreed with the comments of the majority of the Court of Appeal in Re Downshire Settled Estates that the word ‘compromise’ could be interpreted widely, to authorise the imposition of a fresh bargained agreement between the adult beneficiaries and trustees concerning all of the beneficiaries’ interests.

Summary of the court’s inherent jurisdiction to vary a trust

Following Chapman v Chapman, the court only had authority to sanction a variation of a trust in four strictly limited situations. These were in situations of conversion, emergency, maintenance and genuine compromise.

The difficulty with this conclusion was that it limited the court’s ability to sanction the variation of a trust on behalf of a beneficiary who was not sui juris. In doing so, it put an end to the practice of High Court judges in chambers approving such applications to vary a trust on a relatively informal basis.

As a result of the decision in Chapman v Chapman, the Variation of Trusts Act 1958 was enacted.

Variation of a trust under statute

Variation of Trusts Act 1958

This statute is the main method nowadays by which trusts are varied.The long title to the Variation of Trusts Act 1958 expressly confirmed that the purpose behind its enactment was to remedy the restrictive decision in Chapman v Chapman as to when a trust could be varied: