Using Ethnography as a Tool in Legal Research: An Anthropological Perspective Anne Griffiths

6

Using Ethnography as a Tool in Legal Research: An Anthropological Perspective

ANNE GRIFFITHS

The power of law in regulating the social, economic and political life of society is widely acknowledged. Both lawyers and social scientists are concerned with the relationship between law and power—where it is located, how it is constituted and what forms it takes. They address these questions, however, from different perspectives with the result that they provide very different insights into legal analyses and the ways in which law works. Conventional legal theorists limit the scope of their inquiry to an analysis of law-as-text through a rigorous exposition of doctrinal analysis founded on a specific set of sources, institutions and personnel that gain their authority and legitimacy from a formal model of law derived from the nation-state. In contrast, social scientists pursue a broader remit which extends beyond the study of formal legal institutions to take account of the social basis upon which law operates. Anthropology of law falls within this latter category providing a contextual analysis of law that highlights the effects that economic, social and political processes have in establishing differential legal relations among individuals and social groups.

This approach provides an alternative vision of law from the one promoted by conventional legal theory and discourse.1 In promoting another viewpoint anthropological perspectives have made a major contribution to the study of law by challenging Western notions of what constitutes a legal domain2 and by extending the concept of law beyond rule-based formulations to incorporate views of ‘law as process’.3 In adopting actor-oriented perspectives that interrogate who is ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ law4 these approaches have highlighted the frontiers of legality.5 Through pioneering a methodological approach based on ethnography that has focused on local, specific, micro-studies, issues about race, class and gender have been highlighted in ways that expose the inadequacies of legal systems in dealing with them both in theory and practice.

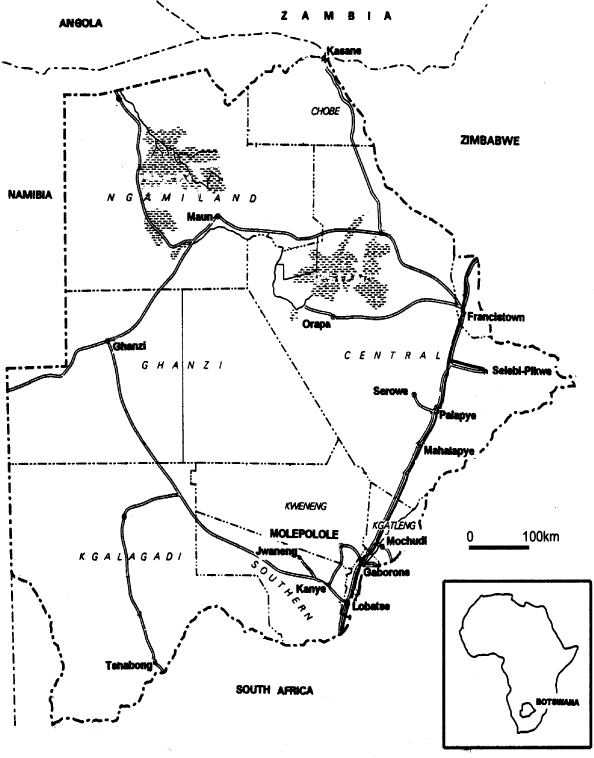

My chapter explores an ethnographic approach to law and the advantages of such an approach when documenting people’s experiences of law in daily life. It is based on fieldwork carried out in southern Africa, among Bakwena6 in Molepolole village, between 1982–89.7

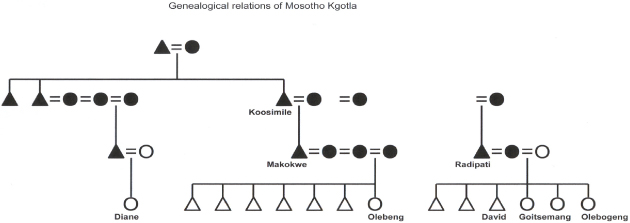

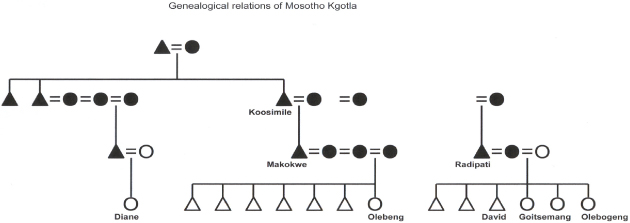

This research focused on women’s procreative relationships with men and their access to family law in Botswana. In pursuing this research agenda, which was aimed at developing the foundation course on family law at the University of Botswana,8 I not only worked with conventional legal sources such as legislation, court records, and court proceedings, as well as interviews with court officials, but also extended my research data to include village members discussions of everyday life, including women’s and men’s life histories and extended narratives of dispute. The life histories were gathered from members of Mosotho kgotla which represented 1 of 73 such social units that made up the village in 1982.9

These life histories and discussions of everyday life were crucial in revealing village people’s perceptions of law, the circumstances under which they do or do not have access to formal legal forums, and in particular, the conditions under which individuals found themselves silenced or unable to negotiate with others in terms of daily life. The latter is especially important for, like other jurisdictions, it is in daily life that the power and authority to negotiate with others has the greatest impact on individuals’ lives. This is because few negotiations become disputes that require handling in a legal arena, such as a court.10 Such information highlights the specific, concrete, lived-experiences that inform people’s lives, a dimension that is often missing from official narratives that focus on substantive and procedural aspects of the legal system as well as its more abstract claims to equality and neutrality.

The life histories and narratives not only document individuals’ experiences but connect them to the broader social polity to which they belong, one that extends beyond institutional forums, such as courts, to incorporate networks revolving around kin, marriage, and varying forms of resources. They provide a picture of continuity and change across two generations that underpins the differences between and among the sexes as well as demonstrating how membership of different family networks shapes women’s and men’s access to resources, including the power to negotiate with one another. How this power is constructed remains unarticulated so far as the formal legal system is concerned, but understanding how it is created and operates is especially important for women given the ways in which their access to resources is mediated through the gendered networks of family and household, in conjunction with the broader economic, political, ideological and social domains of which they form part. For these factors place women at a disadvantage in their dealings with men when it comes to acquiring access to and control over the resources that shape their world.

A. THE HOUSEHOLD AND THE KGOTLA

As with any Tswana village, the organization of Molepolole is structured through administrative units, known as wards and dikgotla,11 which derive from households. It is through households that the political structure of the morafe or polity maintains itself. Kwena society, like other Tswana merafe (polities), revolves around a tightly organized hierarchy of coresidential administrative units. Their political community is conceived of as a hierarchy of progressively more inclusive coresidential and administrative groupings, beginning with households, and extending through kgotlas and family groups, to wards which represent major units of political organization. These are presided over by men. The Chief’s kgotla which is the most senior and powerful ward in the morafe, represents the apex of the administrative and political structure through which the kgosi (‘chief’) exercises his power. When I began my research in Molepolole in 1982, with Mr Masimega who acted as my interpreter,12 there were 6 main wards13 and 73 kgotlas.

B. PROPERTY AND RESOURCES

When it comes to property and resources in Botswana, Kerven has noted that ‘Tswana livelihoods are made within the minimal core of the family and the maximal universe of the southern African economy’.14 Families depend on a combination of ‘crops, cattle and wages’ for their existence which ‘are combined according to a family’s class position and stage in the life cycle’.15 Migration forms an integral part of family life and has done ever since the founding of the Bechuanaland Protectorate in 1885. This has continued into the post-independence period from 1966 but the forms have shifted towards a greater degree of internal rather than external migration, due to development taking place within the country, as well as South African policies now geared to restricting the numbers of external migrants working in South Africa. Most families in Molepolole are dependent on a mix of subsistence agriculture, livestock and cash for their existence and on family members acting co-operatively to pool their resources. This interdependence among family groups based on the foregoing gives rise to what Parson has termed the peasantariat16 who represent the majority of families in Botswana today. However, there are a small group of those who have been able to focus on other activities and to form part of an elite, referred to as the salariat.17 Their focus on education (often to university level) has enabled them to acquire skilled and stable forms of employment, as bureaucrats or government civil servants, which provide access to a whole range of benefits. Examples of both family types exist in Mosotho kgotla through the descendants of Makokwe and Radipati.18

C. ACCESS TO RESOURCES AND THE ROLE OF GENDER

Within families gender operates to constrain women’s access to, and control over, resources. Although most women have access to land their ability to utilize it is dependent upon their raising cash to buy the necessary seedlings and other items necessary for its maintenance and mobilizing the labour necessary for its cultivation. In these activities women, especially from the peasantariat, tend to be dependent on men because of the structure of Kwena society and poor employment prospects compared with those of men.

Kwena society is based on households which form the basis for the political structure of the kgotla and customary law. Authority is based on age and status but women do not have comparable authority with that of men for although they may act as heads of households,19 they can never become headman of a kgotla.20 In addition, material and social circumstances combine to create a situation where it is the households of married men and women that prove the most effective in agricultural production as they have a greater command over the resources required for such production compared with others, such as female-headed households.21

Women also find themselves at a disadvantage when it comes to acquiring livestock. This is due, in part, to succession laws that favour cattle being handed down from father to son, referred to as estate cattle. Although daughters can and do acquire some beasts (where such cattle exist), their share is rarely on a par with that of their brothers, especially their eldest brother who takes over responsibility for the family group on his father’s death.22 Women may inherit livestock from their mother, but a mother’s opportunities for acquiring her own beasts are limited, as these can only derive from certain sources of labour. These include produce from their own (and not their husband’s) land, which may be exchanged for livestock, or which may be used to make beer, which in turn is sold to provide the cash to purchase livestock. Surplus produce rarely exists as most of what is grown is consumed in house and is susceptible to drought, making it extremely hard to acquire livestock in this way. Acquiring money to buy livestock is also difficult for women given poor employment prospects and rates of pay. Even where successful women have to cede control over such livestock to the boys and men who run the cattle posts where they are quartered.

Employment is one of the most important factors affecting the social and economic position of women in Botswana today.23 This is because the money it provides, that is essential for survival, is generally less available to women for a number of reasons. In the formal sector, women are excluded from employment that many men engage in the mining and construction industries. Other jobs, requiring a certain degree of education, are beyond both sexes although women in Botswana, as elsewhere in Africa, are more likely to lack these qualifications than men are.24 The kind of employment open to the majority of women involves domestic service or working as a barmaid or shop assistant. There is competition for such work which is insecure and poorly paid. In this situation women find it hard to negotiate or enforce their terms of service even where these are laid down by law. Men also experience difficulties but they have more options regarding potential employment.

D. DIFFERENTIALLY SITUATED SOCIAL NETWORKS

Many women do not have marital status in Botswana but it is important to note the social contexts in which marriage occurs and the implications that this has for both married and unmarried women. For the peasantariat, representing a substantial proportion of the population in Botswana, marriage still play an important role in providing access to the broader networks of supra-household management and cooperation on which they rely for their subsistence. This is true of Makokwe’s family from Mosotho kgotla where there has been a relatively high rate of kin marriage among members of the older generation and whose access to land has been acquired through their wives’ maternal relatives.

Among the salariat, however, there has been a tendency to limit kin recognition27 in order to circumscribe obligations adhering to these relationships. Among this group women more frequently express negative views on marriage.

Membership of different networks has implications for women and for their power to negotiate their relationships with men. Women within the peasantariat find their choices mediated through their position in relation to male networks and structures of authority which provide the mainstay for their existence. So for example, through male sibling support, some women find themselves with the power of choice which is not available to other women who lack access to this type of network.

Within Mosotho kogtla, Olebeng, who is Makokwe’s youngest child and only daughter, has had several children with different fathers. She has five adult brothers who have all married and had children. In her case, however, neither she nor her family ever had any interest in marriage for her. Among women within this group she is relatively well supported by her siblings who have given her control of the natal household and who plough for her and provide her with food and cash when they can. Other women from the same background are not so fortunate. Diane, for example, who is of the same generation and roughly the same age as Olebeng has not only been abandoned by her brothers but they have expropriated land given to her by her mother. Without her brothers’ support she has found herself unable to negotiate marriage and has had to rely on a series of male partners who have only intermittently provided support for her and her nine children. She represents one of the poorest female-headed households associated with the kgotla.

In contrast, women within the salariat, have a greater degree of power and control over the choices that are open to them. This is the case with Goitsemang. Her father, Radipati, was Makokwe’s half brother but his family have experienced a very different life trajectory from Makokwe’s descendants. Unlike his contemporaries, Radipati was an educated man who educated his children, including his three daughters (at a time when many women received only a nominal education). This helped them acquire formal employment. The eldest unmarried daughter, Goitsemang worked as a nurse in South Africa and then in a management capacity for a construction company in Botswana, enabling her to build a house in the capital city, Gaborone. Her younger unmarried sister, Olebogeng, has also acquired a plot of land in Gaborone by working for the same company. Radipati’s sons were also educated and two of them even went on to acquire university degrees. Through their access to education and skilled, stable employment, the family fits the kind of profile associated with the salariat in that they no longer centre their activities around subsistence agriculture and migrant labour.

Within this family group Goitsemang has had children with two different fathers. But unlike Diane, her relationships had the potential for a customary marriage from which she withdrew and she has now has no interest in marriage as it ‘just brings quarrels’.

Olebeng, Diane, and Goitsemang are within the same generation and age group yet their lives vary considerably. Taking account of the specificity of their lives is important for government planning and policy development related to ‘female headed households’28 as it has been the subject of great controversy surrounding the definition and basis upon which such households as a group should be the recipient of government aid.29

The life histories demonstrate that women’s access to resources is shaped by the type of network to which they belong. So, women within the peasantariat, who operate within the matrix of domestic, agricultural and unskilled labour, find themselves heavily reliant upon the male networks and structures of authority which provide them with support. Women, within the salariat, however, who have stable employment of another king are less reliant on male networks and so experience a greater degree of independence. Not only that, but some of these women have been able to reshape the normative considerations that pertain to women’s dealings with men within a familial context.30 Thus Goitsemang was able to challenge her brother David over control over the natal household by reconfiguring the terms of the discourse in a way that would not have been open to Olebeng or Diane.31