Trustees’ Appointment and Removal; Trustees’ Fiduciary Duties

Chapter 8

Trustees’ Appointment and Removal; Trustees’ Fiduciary Duties

Chapter Contents

The Trustee’s Fiduciary Duties

Having considered how an express trust is formed, it is now time to discuss how that type of trust is managed. The managers of the trust are the trustees. Trustees are subject to a number of duties of both a fiduciary and non-fiduciary nature. They enjoy a number of powers. To gain a holistic view of the trustees’ obligations and powers, you should read Chapter 9 immediately after this chapter.

As You Read

Look out for the following themes:

how a trustee can be appointed and removed;

how a trustee can be appointed and removed;

how a trustee is under a number of obligations imposed upon him but enjoys a number of powers; and

how a trustee is under a number of obligations imposed upon him but enjoys a number of powers; and

how the core obligations of a trustee are ‘fiduciary’. See these as red lines beyond which a trustee must not cross.

how the core obligations of a trustee are ‘fiduciary’. See these as red lines beyond which a trustee must not cross.

Role of a Trustee

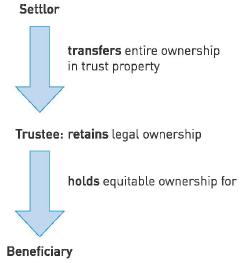

The trustee’s role in the trust may be explained simply in the now-familiar diagram in Figure 8.1.

Figure 8.1 shows the most frequently used way of setting up an express trust: the settlor transfers legal ownership in property to a recipient to hold on trust for the beneficiary. As was seen in Chapter 7, however, it is also equally satisfactory to create an express trust by the settlor declaring themselves to be the trustee and holding the trust property on trust for the beneficiary. In both cases, the beneficiary enjoys an equitable interest in the trust property.

Whether or not a separate trustee is involved, the rights, duties and obligations that trus-tees enjoy and are subjected to remain the same. The trustee holds the legal title to the trust property and manages the trust. The task is mainly administrative.

Appointment of Trustees

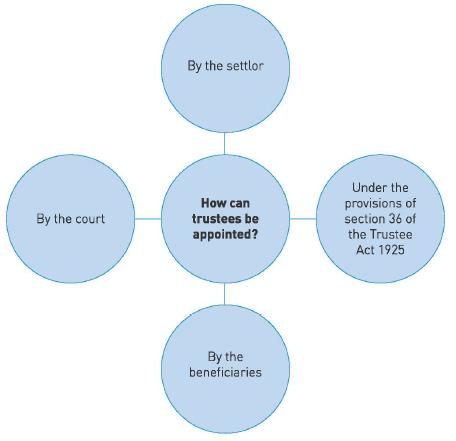

Trustees may be appointed by one of four means, as shown in Figure 8.2.

There can be any number of trustees of a trust, except where the trust property is land. Where the trust property is land, s 34(2) of the Trustee Act 1925 provides that the maximum number of trustees permitted is four. Should more than four trustees be appointed, the first four trustees willing and able to act will be the only trustees of the trust. An exception exists in s 34(3) of the Trustee Act 1925 which provides that the number of trustees for a trust of land used for ecclesiastical, charitable or public purposes can be unlimited.

A single trustee would be the minimum number of trustees permissible although having a single trustee may often be unwise. If any of the trust property is land and a decision is taken to sell it, at least two trustees are needed to sell the land free from the interests of the benefi-ciaries in it.1 This is known as the principle of overreaching (you will have learned about this in Land Law). Even if the trust property does not consist of land, a second trustee can always assist in the administration of the trust and in taking decisions that trustees need to take, such as how and where to invest the trust fund.

Alternatively, or perhaps in addition to individual trustees, many trusts are now adminis-tered by a trust corporation. These are often specialist businesses or departments of large organisations (such as banks) whose task it is to administer trusts. Appointing a trust corporation to administer a trust has the advantage that it should always bring specialist skills and knowledge to the often complex task of trust management. In addition, if the trust property is land, sale of it by a trust corporation also fulfils the requirements of overreaching.2

Appointment by the settlor

This is, of course, the usual way in which trustees are appointed when the trust is first created. Best practice must be for the settlor to declare the trust in a written document, so that there can be no doubt over its exact terms. A trust can be declared orally, providing there are no special formalities that must be fulfilled due to the type of property being left on trust (for example, in the case of land, a trust for which must be evidenced in writing to fulfil the provisions of s 53 (1)(b) of the Law of Property Act 1925).

Whether the trust is declared in writing or orally, the settlor will usually either choose trustees, or alternatively, appoint himself to be a trustee, possibly in combination with other people.

Appointment under s 36 of the Trustee Act 1925

Section 36(1) of the Trustee Act 1925 sets out when new trustees may be appointed. New trustees can be appointed under this section either by a power contained in the trust document providing that someone has the ability to appoint a new trustee (such person could be the original settlor, for example) or, if no such power exists in the trust document, by the existing trustees. If all of the existing trustees have died, then the personal representatives of the last surviving trustee enjoy the power to appoint a new trustee. The power to appoint new trustees is always subject to the maximum number of trustees of land not exceeding four. Any appointment of a new trustee under this section must be in writing.

The power to appoint new trustees under s 36(1) arises when a current trustee:

has died;

has died;

is outside the United Kingdom for a period of more than 12 months;

is outside the United Kingdom for a period of more than 12 months;

wishes to resign from the trust;

wishes to resign from the trust;

refuses to act as a trustee;

refuses to act as a trustee;

is unfit to act as a trustee;

is unfit to act as a trustee;

is incapable of acting as a trustee; or

is incapable of acting as a trustee; or

is a child.

is a child.

In addition, s 36(2) allows there to be an express power to remove a trustee in the trust docu-ment. If such a power exists and is exercised so that a trustee is removed, a replacement trustee can be appointed.

Some of the scenarios listed in s 36(1) have given rise to interesting case law.

Re Walker3 concerned a trust declared in the will of John Walker. He had appointed his wife and a Mr Summers as his trustees. Mr Summers decided to live abroad in April 1899 and when he had not returned by 1 June 1900, Mrs Walker appointed a new trustee in his place. Mr Summers objected. His argument was based on the fact that he had returned to London for a week in November 1899. No power to replace him had arisen in the predecessor to s 36 of the Trustee Act 1925,4 as he had not been absent from the UK for a period of 12 months.

Farwell J agreed with Mr Summers. He rejected Mrs Walker’s argument that the legislation should not be construed literally and said that it was a matter of fact whether the trustee had been absent from the UK for a period of 12 months or more. As he had returned, albeit for a week, he had not been absent for a continuous period of one year, so the power to replace him under this provision had not arisen.

Chitty J considered an example of a trustee being ‘incapable to act’ in Re Lemann’s Trusts.5

The case concerned a trust declared in the will of Frederick Lemann who appointed his wife, Harriet, to be a trustee. The trust provided that a new trustee could be appointed if any trustee was ‘incapable to act’. Harriet had become incapable of acting as a trustee, due to old age and consequent infirmity. She was physically unable to sign a document appointing a new trustee. Chitty J held that she was incapable of acting and that, as she could not appoint a replacement trustee, it was expedient for the court to do so in her place.

Section 36(7) provides that any person appointed as a replacement trustee under s 36 will enjoy all of the same ‘powers, authorities, and discretions’ as the original trustees. The replacement trustee is viewed as though he was an original trustee.

Appointment by the beneficiaries

The beneficiaries of a trust effectively enjoy a right to appoint a new trustee in one particular circumstance. This right is set out in s 19 of the Trusts of Land and Appointment of Trustees Act 1996.

Provided that no-one is nominated in the trust for appointing a new trustee and the beneficiaries are all of full age, enjoy mental capacity and are together all absolutely entitled to the trust property, they may give a direction in writing to trustees to retire from the trust and nominate someone to take their place. It is the retiring trustee who actually appoints their successor. There is no limit on how many trustees the beneficiaries can force to retire and replace in this manner, provided the maximum number of trustees does not exceed four if the trust property is land. The retiring trustee (s) must do everything they can to ensure that the legal title to the trust property is transferred to the new trustee(s) under s 19(4).

Whilst this right might be seen to be useful to the beneficiaries, it will hardly ever be exercised. It depends on the beneficiaries all being of full age, mentally capable and together absolutely entitled to the trust property. The beneficiaries enjoy their interests under a bare trust. In such a case, the beneficiaries probably will not wish to appoint a new trustee(s) but instead will wish to exercise their rights under the rule in Saunders v Vautier.6 This rule provides that in these circumstances, the beneficiaries can collectively bring the trust to an end. The trust ends and the legal title is transferred by the trustees to the beneficiaries for them to enjoy as they wish.

Appointment by the court

The most important power for the court to appoint a new trustee is contained in s 41 of the Trustee Act 1925.(1) provides:

The court may, whenever it is expedient to appoint a new trustee or new trustees, and it is found inexpedient difficult or impracticable to do so without the assistance of the court, make an order appointing a new trustee or new trustees either in substitution for or in addition to any existing trustee or trustees, or although there is no existing trustee.

Section 41(1) then goes on to give some examples of when the court may appoint a new trustee under this section. These are when an existing trustee lacks capacity, has been declared bankrupt or, if a company, has been liquidated or dissolved.

For the provision in s 41 to operate, it must be ‘inexpedient difficult or impracticable’ to appoint a new trustee without the court’s assistance. This was seen to be the case in Re Lemma’s Trusts,7 where Harriet Lemann was not physically capable of signing any documentation herself to appoint a new trustee and the court had to appoint a replacement for her.

A further example, albeit on more unusual facts, of it being ‘inexpedient difficult or impracticable’ to appoint a new trustee without the court’s assistance was given by the facts of Re May’s Will Trusts.8 Unlike in Re Lemma’s Trusts, there was no evidence in this case that the trustee was incapable of acting as a trustee within the meaning of s 36(1) of the Trustee Act 1925.

The facts concerned the trust declared in the will of Herbert May. He appointed three trustees: George May, Frederick Stanford and his wife, Marguerite May. Marguerite was in Belgium when the German forces invaded at the beginning of the Second World War. She was therefore unable to return to the UK. The two other trustees brought an action claiming that she was ‘incapable of acting’ within the meaning of s 36(1) and that a different individual be appointed as a trustee within her place.

Counsel for Mrs May pointed out that all of the previous authorities on trustees being ‘incapable’ tended to define the term as the trustee being mentally or physically incapable of acting. Crossman J appeared to accept that definition as applying to s 36(1) in his short judgment, as he said that he could find no evidence that Mrs May was ‘incapable’ of acting within s 36(1) as it had previously been interpreted. He did, however, hold that the court was able to appoint a new trustee in place of Mrs May under the power contained in s 41. It appears that his judgment was as a result of a pragmatic decision that the trust would benefit from the appointment of a trustee who was in a position to act as such.

The case illustrates that the power given to the court in s 41 is a stand-alone power and that, provided it is ‘inexpedient difficult or impracticable’ for a new trustee not to be appointed without the court’s assistance, the court will appoint a new trustee.

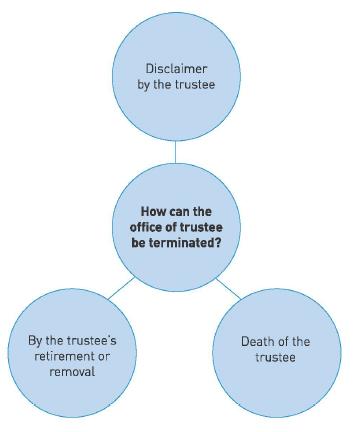

Termination of Trusteeship

The office of trustee may be terminated in any one of three main ways, as shown in Figure 8.3.

Disclaimer by the trustee

Being a trustee is not compulsory! When chosen by the settlor, there is no obligation on the individual or corporation to accept the office of trustee.The office of trustee may be disclaimed, but it must be disclaimed before any acts associated with being a trustee (for example, investing the trust property) are undertaken.

Disclaiming being a trustee cannot be undertaken in part. The entire office of trustee must be disclaimed, as was shown in Re Lord and Fullerton’s Contract.9

The facts concerned a trust declared in the will of Samuel Lord. He appointed various people to be his trustees, including his son, Samuel Lord the younger. The trust property consisted of real and personal property both within the United States of America and outside it. Samuel Lord the younger purported to disclaim all of the property located outside of the United States. When land was sold in England by the remaining trustees, the buyer brought an action claiming that good title to the property had not been proven to him. His case was that Samuel Lord the younger could not disclaim part only of the trust — that he was either a trustee of the entire trust or he was not a trustee at all.

The Court of Appeal agreed with the buyer. Lindley LJ explained his reasoning as follows:

A testator intends when he makes such a will as this that his … trust shall have the joint judgment of all the trustees … and I do not think that it is competent for any trustee to say, ‘I will attend to some of the trusts, and I will not attend to others’. It is competent for him to say that he will have nothing to do with the trusts; other-wise a testator would be able to saddle people with duties of an onerous description without their having any opportunity to get rid of them. But it is not competent for him to accept the office as to some part of the estate and not accept it as to the rest.10

If a trustee wishes only to administer selected parts of the trust, his wish to do so should be discussed with the settlor when the trust is created. If he wishes to have that individual as a trustee for part only of his property, the settlor would have to create more than one trust of his various property, or have more than one set of trustees to administer the property.

The reason behind this inability to disclaim part only of a trust appears to be certainty in favour of any buyer of trust property. The buyer must be confident that he is dealing with the right trustees. It would not be fair for a buyer to have to enquire of each trustee whether or not he had disclaimed the particular trust property that is being sold. It is far simpler if those who appear to be the trustees actually are the trustees. The trustee does not have to accept his office when the trust is created and may disclaim it even after the trust has been created, provided he has not effectively ratified his own office by undertaking any act which is consistent with being a trustee.

Death of the trustee

When a trustee dies, the surviving trustees assume his responsibilities and continue to be the trustees of the trust.(1) of the Trustee Act 1925 contains a power for either a person so nominated in the trust or the surviving trustees to appoint a new trustee in their place. Such appointment must be in writing.

If the trustee is the last one of the original trustees to die, his personal representatives will become the new trustees of the trust under ss of the Administration of Estates Act 1925 until they appoint a new trustee under s 36(1) of the Trustee Act 1925.

By the trustee’s retirement or removal

A trustee may decide to retire from the trust or be removed from it. The distinction is concep-tual: retirement suggests that the trustee has voluntarily stepped down from their office, whilst removal implies he was obliged to leave his position.

Retirement

There are five main ways in which a trustee can retire:

[a] under an express provision in the trust deed;

[b] under s36of the Trustee Act 1925;

[c] under s39of the Trustee Act 1925;

[d] by a court order; or

[e] under s19of the Trusts of Land and Appointment ofTrustees Act 1996.

(a) Under an express provision in the trust deed

It is always possible for a trust deed to contain an express clause permitting a trustee to retire. A trustee may, for example, be given the right to retire when he feels like it, providing a suitable replacement can be found. In such a situation, the retiring trustee simply needs to comply with the provisions of the relevant clause.

(b) Under s 36 of the Trustee Act

A trustee may retire under s 36 if he ‘desires to be discharged from all or any of the trusts or powers reposed in or conferred on him’. In this case, the retiring trustee can be replaced by someone chosen either by a person nominated in the trust deed to choose a replacement trustee or (if there is no such power) by the remaining trustees.

(c)Under s 39 of the Trustee Act

Whilst s 36 of the Trustee Act 1925 provides that a retiring trustee should be replaced, s 39 sets out a provision enabling a trustee to retire and not be replaced. This provision can be exercised providing there are at least two individual trustees or a trust corporation who remain to administer the trust. Under s 39, the trustee must retire by deed.

(d)By a court order

The court has an inherent jurisdiction to sanction the retirement of any trustee.

(e)Under s 19 of the Trusts of Land and Appointment of Trustees Act

This little-used provision means that beneficiaries of full age, mental capacity and together absolutely entitled to the trust property can effectively force a trustee to retire and be replaced with someone of their own choosing. This is rarely used because beneficiaries who find themselves in this position usually prefer to bring the trust to an end under the rule in Saunders v Vautier11 so that they can enjoy their property themselves, free from the restrictions of the trust.

Removal

There are five ways in which a trustee can be removed from office:

[a] by express provision in the trust deed;

[b] under s36of the Trustee Act 1925;

[c] under s41of the Trustee Act 1925; or

[d] under the court’s inherent jurisdiction.

(a) By express provision in the trust deed

Again, an express clause in the trust deed setting out circumstances in which a trustee must step down from his office is permitted. This may occur if, for example, the trustee breaches a fiduciary duty.

(b) Under s 36 of the Trustee Act

Section 36 sets out when a trustee can be removed from office without obtaining their consent. Such instances include when the trustee is located outside of the UK for more than 12 months, or he refuses to act as a trustee, or is unfit or incapable of acting as a trustee. A child appointed as a trustee can also be removed under this section, although children can only be trustees of implied trusts in any event.12

(c) Under s 41 of the Trustee Act 1925

The power of the court under s 41 to appoint a new trustee is a power to appoint ‘either in substitution for or in addition to’ the existing trustees. The section, therefore, allows the court to remove a trustee from office, if it decides to appoint a new trustee in their place.

(d) Under the court’s inherent jurisdiction

Again, the court enjoys an inherent jurisdiction to force a trustee out of office. Guidance on this ability was offered by the Privy Council in Letterstedt v Broers.13

The case concerned the will of Jacob Letterstedt who owned a successful brewing business in South Africa. He declared a trust in his will, in which he left the business to his daughter. Until she reached 25 years old, the trust of the business was to be administered by a board of trustees and the business itself by a manager. The daughter was to be entitled to two-thirds of the profits of the business until she reached 25. She brought an action as she believed the board of trustees had taken too much money for themselves. She claimed just over £28,500. Importantly, she also wanted the board of trustees replaced by new trustees as she had lost confidence in the current trustees. The issue for the Privy Council was in what circumstances the court should exercise its inherent jurisdiction to replace trustees and whether the trustees of this particular trust should be replaced.

In delivering the opinion of the Privy Council, Lord Blackburn thought that the jurisdic-tion of a court to replace trustees was part of its overall jurisdiction to ensure that trusts are properly executed by the trustees. He found it impossible to lay down definitive guidelines as to when the court should order the removal of trustees, other than the court’s ‘main guide must be the welfare of the beneficiaries’.14

The court had to consider whether it was in the best interests of the beneficiaries to order the removal of the trustees. On the facts of the case, it was. The beneficiary had not proved that the trustees had acted fraudulently towards her by taking such sums from her entitlement and failing to ensure that the accounts of the trust were independently checked. Nonetheless, the relationship of trust and confidence which had to exist between a trustee and a beneficiary had broken down, so it was in her interests that the trustees be removed from office.

The trustees were wholly innocent in this case as allegations against them by the benefi-ciary had not been proven. That was not thought to matter. It was the claimant’s welfare that was the key issue; if her welfare would be improved by the trustees being replaced, then the court would order their removal and replacement.

The issue arose again in Re Wrightson.15 The trustees of a trust had, according to the benefi-ciaries, effectively invested the trust fund in an investment which was not authorised according to the terms of the trust. The beneficiaries brought an action seeking a declaration from the court that the investment was a breach of trust and wanting relief from it. This was duly granted. In a later action, some of the beneficiaries also sought the trustees’ removal from their office.

After quoting from Lord Blackburn’s test of whether the removal of the trustees would be for the ‘welfare of the beneficiaries’ in Letterstedt v Broers, Warrington J summed up the position when the court could order the trustees’ removal as:

You must find something which induces the Court to think either that the trust property will not be safe, or that the trust will not be properly executed in the interests of the beneficiaries.16

On the facts, the life tenant had died, thus leaving solely beneficiaries in remainder, whose interests had vested in them. All that remained was for the trust to be wound up and the legal title in the property transferred to the remainder beneficiaries. Taking this into account and also the time and money involved in replacing trustees, Warrington J held that it was not in the beneficiaries’ welfare that the trustees be replaced. Even though the trustees in the case were clearly guilty of a breach of trust, they were not replaced, as the welfare of the beneficiaries was the overriding concern that could trump every other issue.

ANALYSING THE LAW ANALYSING THE LAW |

Do you think the decisions in Letterstedt v Broers and Re Wrightson are compatible? In the former, the trustees were replaced, although there was no objective reason for doing so. The beneficiary had merely lost confidence in them. In the latter, the trustees had breached the trust, but pragmatic reasons appeared to justify their retaining office. Do you think there is any guiding principle behind these decisions or are both just examples of pure pragmatism by the courts?

Having seen how trustees are appointed and how they can leave their office, their obligations whilst in office must now be considered.

Managing the Trust

Once appointed, the trustees’ main obligation is to manage the trust fund for the benefit of the beneficiaries. The trustees will have been carefully chosen by the settlor to fulfil their role. Administering the trust is their responsibility.

Whilst administering the trust, the trustees have a number of duties. These can be split into two types: fiduciary and non-fiduciary.

The nature of the relationship between the trustee and beneficiary is fiduciary. ‘Fiduciary’ was defined by Millett LJ in Bristol & West Building Society v Mothew17 as follows: