TRIPS Flexibilities and National Implementation (1) Patentable Subject Matter and Patentability Requirements

12

TRIPS Flexibilities and National Implementation

(1) Patentable Subject Matter and Patentability Requirements

THE WTO PANEL explained in China – Intellectual Property Rights1 that the nature of obligation and the scope of national discretion which is allowed differ between Part II and Part III of the TRIPS Agreement.2 Part II introduces TRIPS-regulated substantive minimum standards concerning the availability and scope of, and exceptions to IPR, whereas Part III relates to enforcement of IPRs and allows considerable discretion to enforcement authorities as to the means to attain the goals delineated by the TRIPS Agreement. There are, however, provisions also in Part II which leave significant policy options to Members. Notable examples include Article 27 concerning patentable subject matter, and Article 39.3 relating to test data submitted to regulatory authorities for marketing approval. This chapter explores how certain TRIPS ‘flexibilities’ have been interpreted and recommended as being beneficial to developing countries. India is examined here because of the country’s leading role in these discussions. This chapter also addresses the question of ‘evergreening’, which section 3(d) of the Indian Patents (Amendment) Act 2005 purports to prevent for public health reasons.

I TRIPS FLEXIBILITIES RELATING TO PATENTABLE SUBJECT MATTER

A Suggestions made by International Bodies on the Patentability Criteria for Developing Countries

Article 27 under section 5 (patents) of Part II of the TRIPS Agreement, entitled ‘Patentable Subject Matter’, provides flexibilities in relation to patentable subject matter and patentability requirements, as well as for the possible exclusions from patentable subject matter. Article 27.1, first sentence, stipulates that ‘patents shall be available for any inventions, whether products or processes, in all fields of technology, provided that they are new, involve an inventive step and are capable of industrial application.’ It thus makes it obligatory that Members grant patents irrespective of whether the invention is a product or a process, and irrespective of the field of technology. Members cannot exclude from patent protection whole classes of inventions in fields of technology. Article 27.1 further provides that ‘patents shall be available and patent rights enjoyable without discrimination as to the place of invention, the field of technology and whether products are imported or locally produced.’ Thus, Members are not allowed to impose conditions of grant and enjoyment of patent rights which amount to discriminating one field of technology against others.

Article 27.2 regulates the conditions of exclusion concerning individual cases and provides that Members may exclude from patentability ‘inventions, the prevention within their territory of the commercial exploitation of which is necessary to protect ordre public or morality’, and Article 27.3 allows exclusion from patentability of certain categories of inventions (see chapters 4 and 5).

Many commentators and international organisations have made policy recommendations on the flexibilities that Article 27 of the TRIPS Agreement offers. For example, the UNCTAD-ICTSD Resource Book on TRIPS and Development (The Resource Book)3 explains in detail where flexibilities lie in the TRIPS Agreement. An explanatory note to the book states that its purpose is to provide a ‘sound understanding of WTO Members’ rights and obligations’, with a view to clarifying ‘the implications of the Agreement, especially highlighting the areas in which the treaty leaves leeway to Members for the pursuit of their own policy objectives, according to their respective levels of development.’4

The Resource Book cites Article 27 as one part of the Agreement that contains a variety of flexibilities, including the fact that it does not define what an ‘invention’ is and provides suggestions that Members may consider,5 such as:

- limiting ‘invention’ only to ‘technology’ (to the exclusion of business method or software),6 given the wording ‘in all fields of technology’ in Article 27.1 of the TRIPS Agreement and the example of the EPO Patent Examination Guidelines;

- opting for a narrow scope of patentability relating to plants and animals, confining it to microorganisms that have been genetically modified;7

- excluding cells, genes, and other sub-cellular components from patentability because they are not visible but are not ‘microorganisms’ and therefore are not subject to the obligation under Article 27.3(b).8

In a similar vein, The Resource Book raises an interpretative question, inter alia, as to whether Article 27.1 obliges Members to protect ‘uses’ as such, for instance, new uses of known products, in addition to products and processes.12 The Resource Book points out that because the TRIPS Agreement only obliges them to grant patents for products and processes (Article 27.1), it is left unclear whether the protection for processes covers uses or methods of use. WTO Members are therefore free to decide whether to allow the patentability of the uses of known products, including for therapeutic use, and are certainly free to adopt the Swiss formula approach.13

the [2001 Doha] Declaration enshrines the principles that agencies such as WHO have publicly advocated and advanced, namely, the reaffirmation of the right of WTO Members to make full use of the flexibilities of the TRIPS Agreement in order to protect public health and promote access to medicines. An important flexibility in this respect is the right of WTO Members to define the patentability criteria as referred to under the TRIPS Agreement in accordance with their particular national priorities. This may be an important tool for the promotion of genuinely new and inventive pharmaceutical products.14

According to the WHO-UNCTAD-ICTSD Pharmaceutical Guidelines, the TRIPS Agreement does not define the criteria of ‘novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability’ and therefore, each WTO Member has discretion to determine the criteria and recommends, notably, that:

- combinations of known active ingredients should be deemed non-inventive as the synergy between the components are obvious to a person skilled in the art. However, if a new and non-obvious synergistic effect is properly demonstrated by biological tests and appropriately disclosed in the patent specifications, this could be considered as a basis for patentability;15

- new formulations, compositions and processes for their preparation should generally be deemed obvious, but could exceptionally be patentable, if a truly unexpected or surprising effect is obtained;

- new doses of known products for the same or a different indication do not constitute inventions;

- new salts, ethers, esters and other forms of existing pharmaceutical products can generally be obtained with ordinary skills and are not inventive, but, exceptionally, if appropriately conducted clinical tests data, described in the specifications, demonstrate unexpected advantages in properties as compared to what was in the prior art, are patentable;

- processes to obtain polymorphs may be patentable in some cases if they are novel and meet the inventive step standard;

- claims relating to the use, including the second indication, of a known pharmaceutical product can be refused, inter alia, on grounds of lack of novelty and industrial applicability;

- polymorphism is an intrinsic property of matter in its solid state. Polymorphs are not created, but found. Patent offices should be aware of the possible unjustified extension of the term of protection arising from the successive patenting of the active ingredient and its polymorphs, including hydrates/solvates. Processes to obtain polymorphs may be patentable in some cases if they are novel and meet the inventive step standard;

- single enantiomers (optical isomers) should generally not be deemed patentable when the racemic mixture was known but processes for the obtention of enantiomers, if novel and inventive, may be patentable;

- claims relating to the use, including the second indication, of a known pharmaceutical product can be refused, inter alia, on grounds of lack of novelty and industrial applicability.

- polymorphism is an intrinsic property of matter in its solid state. Polymorphs are not created, but found. Patent offices should be aware of the possible unjustified extension of the term of protection arising from the successive patenting of the active ingredient and its polymorphs, including hydrates/solvates. Processes to obtain polymorphs may be patentable in some cases if they are novel and meet the inventive step standard;

The US, Europe and Japan have considerably different constructions and legal formulations in delineating the scope of patentable inventions (see chapter 3; see also footnotes 11 and 12 of this chapter). In the European countries, certain kinds of inventions were excluded by statutes, whereas in the US, patentability questions have been decided judicially. While statutory determination may lead to certain predictability, judicial determination could be adaptable to the nature of inventions that evolve with science, technology and market conditions, depending, however, on how objectively and competently the standards are actually applied. The Expert Group on Biotechnological Inventions for the European Commission emphasises that fundamental concepts in patent law, such as discovery, invention or technical character, are ‘subject to evolution’.16

Additionally, the timing of examination among different jurisdictions tends to create differences in the evaluation of prior art and, therefore, of ‘inventive step’. According to a 2007 report of the Japanese Patent Office (JPO),17 the most common reason for rejecting patent applications is lack of inventive step. This happens slightly more often in Japan than in the US or in Europe. This is mainly because the relevant prior art in the form of scientific and technological literature consulted by the JPO is later in time than the US or the EPO, due to the system in Japan of not examining the application unless such a request is made formally. In most countries, however, the lack of ‘inventive step’ can be dealt with effectively by applicants and amended by subsequent action improving the specifications, in contrast to rejection on the grounds of lack of novelty. Importantly, the perspective from which patent offices or courts examine patents is that properly administered patent protection ultimately and generally contributes to innovation and encourages R&D.

The Resource Book seems to be proposing that it is in the interest of developing countries if TRIPS provisions are interpreted to allow a narrow scope of IPR protection and to create high hurdles for granting patents. It explains that:

. . . at least from the medium- and long-term perspective, the economic effects of the patent provisions depend largely on the levels of development of countries and sectors concerned, the speed, nature and cost of innovation, as well as on the measures developing countries may take in adopting the new framework. The introduction of patents will entail sacrifices in static efficiency while benefits for most developing countries in terms of dynamic efficiency are uncertain . . . particularly to the extent that research and development of drugs for diseases prevalent in developing countries (such as malaria) continues to be neglected.18

Broadly speaking, the content and the level of patent examination may depend on the scientific and technological capabilities of a given society. However, between the actual patent law provisions on patentability and its economic effects on matters such as prices, there seem to be many intervening market and institutional factors such as the size of the market, entry and investment conditions, price regulations, etc. There may not be many patent applications anyway in less developed countries. How the patentability criteria should be determined in relation to ‘the levels of development of countries’ remains unclear.

The Resource Book, on the question of patent protection of biotechnologies relating to animals and plants, for example, cites the recommendations adopted by the UK Commission on Intellectual Property Rights (CIPR):19 ‘Those developing countries with limited technological capacity should restrict the application of patenting in agricultural biotechnology consistent with TRIPS, and they should adopt a restrictive definition of the term “microorganism”.’20

Would a reduced scope of patentable subject matter and higher patentability standards, particularly of inventive-step, lead necessarily to a lesser number of patents, a reduction of product prices, and otherwise always be helpful for developing countries? In what ways would restrictions on the patentability of certain chemical forms help public health? And would the choice of policy on patentability depend always on the stage of development, as the CIPR suggests?

B R&D on Natural Products

Natural product (NP)-based pharmaceutical R&D21 has been almost totally abandoned by large pharmaceutical companies22 for technological23 and other reasons.24 However, natural products or NP-derived product research could still be attractive sources of research, technology and know-how transfer for R&D.25 It could create both local business and opportunities for scientific and technological learning. For example, inventions relating to biochemistry (microorganisms or enzymes and peptides) contain on average many more scientific citations, in comparison to inventions in other technological fields.26 One of the reasons is that in biochemistry fields, researchers undertaking basic research and applied research tend to overlap.27

It certainly is necessary to prevent the plundering of biological resources and of ideas couched in traditional knowledge29 from developing countries without appropriate reward. Patents are related to traditional knowledge in as much as they are granted by virtue of novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability. If biological resources and/or related traditional knowledge constitute prior art for the invention for which the patent is sought, examiners should take this into account to avoid granting erroneous patents.30 It is also a common understanding and practice in all countries that a mere ‘discovery’ of something already existing in nature is not patentable (see chapter 3). Ways to commercialise innovative products using biological resources vary in different fields such as seeds, food, cosmetics or medicines, depending, for example, on the number of players in the market and the ways in which biological resources contribute to innovation.31 Developing countries may be interested in encouraging and investing in science, research and innovative technologies related to these fields to develop new products themselves. This could be helpful for creating business in health research in developing countries, as seen in the international joint research centres in many Asian countries such as China, Malaysia and Vietnam. From the perspective of strengthening domestic science and technology programmes to encourage innovation by domestic inventors, there seems to be no rational reason for minimising, for example, the definition of microorganisms.

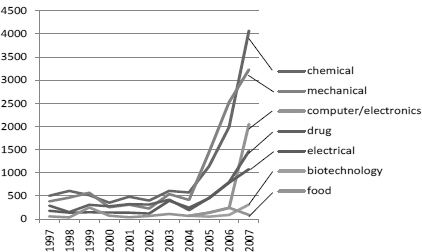

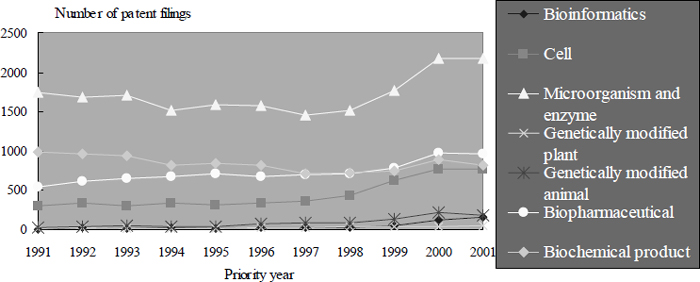

In many countries (Japan in particular), patenting of inventions relating to microorganisms is the most frequent among life-science related fields (see Figure 12.1 for the case of Japan), but the mere fact of a great number of patents does not mean that they encroach upon the rights of others to undertake research. Under the Budapest Treaty,32 the patent applicants of inventions using microorganisms not easily available must deposit the microorganisms at a depository. A third party, to satisfy the enablement requirements for his own invention, can request depositary institutions to furnish deposited microorganisms for study and research. In this field, therefore, the patent system facilitates the disclosure of scientific information probably more than in other fields, without being an obstacle to others’ activities.

Patents for basic, post-genomic biotechnologies (receptors, ESTs, etc) are much less numerous, but their scope could be much wider and might involve allegations of infringement if used without the right holder’s authorisation. On balance, however, for research activities, the proper functioning of the patent system, which is to disclose the relevant scientific and technological information, is helpful. This depends also on the field of technology. What is also important would be that patentability criteria are clear and consistently applied, to give predictability to the users of the system.

Figure 12.1: Patent Filings ofmicroorganisms and Enzymes in Japan

Tamada et al, ‘Science linkages in technologies patented in Japan’ (2004) RIETI Discussion Paper Series 04-E-034, 12. Many patents are filed by universities and ventures, and increased since 1997 at the same time as patenting in other biomedical technologies.

Although the level of sophistication in the patent examination may broadly depend on the technological levels of a country, this does not mean that less developed countries should always have lower standards of IPR protection. For example, a broad scope and a high level of protection may be suitable for developing countries, including least developed countries (LDCs), to create appropriate investment environments for doing bioscience R&D using microorganisms, which could be a suitable technological field.

The criteria of patentability that are ‘most appropriate for the specific level of development’33 may not be so easy to determine. An ‘appropriate’ patentability policy ideally would create a ‘competitive edge’ for a country in light of the globalised research and technological environment and vis-à-vis investors and possible product or licensing markets. How to make such a policy work and produce economic effects over a particular time-span could be a challenging question. Micro-managing different criteria in different technological fields in one country would also be difficult.

In the pharmaceutical and biotech fields, for example, research itself has become a globalised process where the upstream activities are promoted by early leads under the National Institute of Health (NIH) programmes, and downstream research (such as molecular optimisation) is done increasingly in developing countries, by Chinese and Indian researchers in particular.34 Clinical studies are also increasingly outsourced to these countries, and from the point of view of contract manufacturing organisations (CMO) and contract research and manufacturing services (CRAMS) organisations, strong patent protection and data exclusivity are lacking in these countries.35 This conflicts with the view that such protection is not suitable for ‘developing countries’.

There are important and inherently more difficult policy and implementation issues than a mere IP policy. For example, merely enlarging or reducing the scope of patentability would be meaningless unless such patent policy is implemented consistently and effectively, in a way linked to positive efforts to raise the scientific and technological levels of the country and to increase the competitiveness of its own industry. Unless universities, research institutes and industry make independent efforts to substantially increase creative R&D, IP policy may not contribute much to local business development. Government efforts to coordinate various domestic efforts would play a crucial role in developing viable business and local industry.

II EVERGREENING, PATENTABILITY REQUIREMENTS AND PUBLIC HEALTH

The above-mentioned WHO-UNCTAD-ICTSD Pharmaceutical Guidelines suggest that the ‘flexibilities’ contained in Article 27.1 of the TRIPS Agreement be used for public health purposes, by restricting the patentability of certain forms of chemical compounds, in addition to narrowing the scope of patentable inventions, to reduce the scope of claims and to raise the standards of judging ‘inventive-steps’. This approach seems to be one of the guiding principles in the evolution of the Indian Patents Act 1970 and its Amendment Act 2005. In the following part of this chapter, the nature of chemical forms of inventions is explored in its relation to ‘evergreening’ with a view to clarifying this concept, which has increasingly been used globally (and rather pejoratively) in the context of pharmaceutical patenting practice. The prevention of evergreening is the objective of section 3(d) of the Indian Patents (Amendment) Act 2005, legislation which has been considered as a model by several developing countries. The Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB)36 in Novartis v Union of India stated that:

It appears lndia has adopted stricter standard[s] of protection with respect to novelty and inventive step taking consideration of its public welfare particularly health concerns permitted by Doha declaration . . .37

A TRIPS 27.1 Flexibilities and India

Section 3(d), which provided in the Patents Act 2002, that ‘the mere discovery of any new property or new use for a known substance [is not patentable]’ was substituted in 2005 to read: ‘the mere discovery of a new form of a known substance which does not result in enhancement of the known efficacy of that substance or the mere discovery of any new property or new use for a known substance [is not patentable]’. Section 3(d) is accompanied by the following ‘explanation’, whose relationship to the main provision of 3(d) is not entirely clear:

For the purposes of this clause, salts, esters, ethers, polymorphs, metabolites, pure form, particle size, isomers, mixtures of isomers, complexes, combinations and other derivatives of known substance shall be considered to be the same substance, unless they differ significantly in properties with regard to efficacy.

In 2007, the Indian government explained at the WTO Trade Policy Review (TPR) of India38 that the Indian Patents (Amendment) Act 2005, seeks to balance IP protection with public health, national security, and the concerns of public interests.39 According to the Indian reply to questions at the TPR, the legislative purpose of section 3(d) was to prevent the extension of patent life by evergreening and by ‘trivial patents’ that block generic entry,40 elaborated to protect public interest in preventing ‘evergreening’.

In Novartis v Union of India,41 the High Court of Madras, quoting the Supreme Court view that the ‘ascertainment of legislative intent is a basic rule of statutory construction’, stated that:

If we read the Parliamentary debate on Ordinance 7/2004, it appears that there was a widespread fear in the mind of the members of the House that if Section 3(d) as shown in Ordinance 7/2004 is brought into existence, then, a common man would be denied access to life saving drugs and that there is every possibility of ‘evergreening’.42

In the 2004 Order in the process of amending the Indian Patents Act 1970,43 the phrase, ‘a mere new use’, was used in the text of section 3(d) and, therefore, a new use could be patentable, which was to be reversed in the amendment of 2005 by the deletion of the word ‘mere’. According to the Madras High Court in the Novartis v Union of India case:

the Parliamentary debates show that welfare of the people of the country was in the mind of the Parliamentarians when Ordinance 7/2004 was in the House. They also had in mind the International obligations of India arising under “TRIPS” and under “WTO”.44

In the same case, the Madras High Court noted the scope for national discretion that the TRIPS provisions leave, by Articles 1, 7 and 27. According to the judgment:

Article 7 of ‘TRIPS’ provides enough elbow room to a Member country in complying with ‘TRIPS’ obligations by bringing a law in a manner conducive to social and economic welfare and to a balance of rights and obligations. Article 1 of ‘TRIPS’ enables [sic] a Member country free to determine the appropriate method of implementing the provisions of this agreement within their own legal system and practice. But however [sic], any protection which a Member country provides, which is more extensive in nature than is required under ‘TRIPS’, shall not contravene ‘TRIPS’. Article 27 speaks about patentability.45

On the point of Article 27 of the TRIPS Agreement and national patentability criteria, the IPAB decision on the Novartis case on appeal endorsed what the Madras High Court had asserted. The IPAB also invoked the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health as follows:

Since India is having a requirement of higher standard of inventive step by introducing the amended Section 3(d) of the Act, what is patentable in other countries will not be patentable in India . . . As we see, the object of amended Section 3(d) of the Act is nothing but a requirement of higher standard of inventive step in the law particularly for the drug/pharmaceutical substances. This is also one of the different public interest provisions adopted in the patent law at the pre-grant level, which as we see, are also permissible under the TRIPS Agreement and to accommodate the spirit of the Doha Declaration which gives to the WTO Member states including India the right to protect public health and, in particular, to promote access to medicines for all.46

Thus, for the Madras High Court, section 3(d) provides ‘a higher standard of inventive step’. On the accounts made by the Solicitor General of India and other defendants, the Madras High Court observed that:

India, being a welfare and a developing country, which is predominantly occupied by people below the poverty line, has a constitutional duty to provide good health care to its citizens by giving them easy access to life saving drugs. In so doing, the Union of India would be right, it is argued, to take into account the various factual aspects prevailing in this big country and prevent evergreening by allowing generic medicine to be available in the market.47

a known substance in its new form such as amorphous to crystalline or crystalline to amorphous or hygroscopic to dried, one isomer to other isomer, metabolite, complex, combination of plurality of forms, salts, hydrates, polymorphs, esters, ethers, or in new particle size, shall be considered [sic] same as of known substances unless such new forms significantly differ in the properties with regard to efficacy.48

Furthermore, the Draft Manual 2008 states that the comparison with regard to properties or enhancement of efficacy is required to be made at the time and date of filing the application or priority date if the application is claiming the priority of any earlier application but not at the stage of subsequent development.49 The same Manual asserts the meaning of ‘efficacy in pharmaceutical products’, by reiterating what was decided by the Madras High Court in the Gleevec case, namely, that:

. . . going by the meaning for the word ‘efficacy’ and ‘therapeutic’ . . . what the patent applicant is expected to show is, how effective the new discovery made would be in healing a disease/having a good effect on the body? In other words, the patent applicant is definitely aware as to what is the ‘therapeutic effect’ of the drug for which he had already got a patent and what is the difference between the therapeutic effect of the patented drug and the drug in respect of which patent is asked for.50

Thus, the intention of the Indian Parliament in adopting section 3(d) seems to have been to prevent ‘evergreening’ as a means to provide good public health policy. However, the meaning of ‘evergreening’ is not readily understandable. Is it possible to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between the legal provision on patentability in section 3(d) of the Patent Acts on the one hand, and good public health policy results, on the other? There may be a host of intervening factors between the two, and the results may not be a policy or ‘public’ health. Moreover, it may not be possible, technically, for the patent applicant to explain, at the time of patent filing (ie, before clinical studies are undertaken) the enhanced ‘therapeutic’ efficacy of the molecule as adequately as the Madras High Court and the Draft Manual 2008 require. Further clarification of the meaning of ‘efficacy’ in section 3(d) would therefore be necessary for the application of this provision. Such a clarification would be needed all the more if this provision is expected to have a social impact, as was the original legislative intent. However, it may be difficult to predict the social impact of the patentability requirements of chemical forms, for the reasons explained below.

Despite these uncertainties, section 3(d) of the Indian Patents (Amendment) Act 2005, seems to have become a model for developing countries. The Philippines introduced the same provisions as section 22.1 in its Intellectual Property Code.51 The Maldives, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia and Bangladesh were also reported to have been considering adopting provisions similar to section 3(d) of the Indian Patents (Amendment) 2005.52

In November 2009, TC James, former Director of Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs) Division, Ministry of Commerce & Industry of India, and today Director of the National Intellectual Property Organization, New Delhi, published a report, ‘Patent Protection and Innovation: Section 3(d) of the Patents Act and Indian Pharmaceutical Industry’ on behalf of the Indian Pharmaceutical Alliance (IPA).53 The Report responds to criticisms54 from the developed country pharmaceutical industry that section 3(d), by prohibiting certain forms of inventions from being patented, does not encourage local incremental innovation. The TC James Report states that: ‘Removal of Section 3(d) will result in evergreening and delay in the entry of generics thereby adversely affecting public health’, and points out that the ‘[s]tage of development of a country has to be borne in mind while prescribing patent standards’.55

The TC James Report cites the conclusion from the recommendations made by the UK Commission on Intellectual Property (CIPR)56 and explains that the CIPR ‘looked into the issue of integrating development objectives into the making of policy on IPRs world-wide’, and ‘felt that “developing countries should not feel compelled or indeed be compelled, to adopt developed country standards for IPR regimes.”’57 In this regard, according to TC James:

[t]he underlying principle should be to aim for strict standards of patentability and narrow scope of allowed claims, with the objective of:

—limiting the scope of subject matter that can be patented

—applying standards such that only patents which meet strict requirements for patentability are granted and that the breadth of each patent is commensurate with the inventive contribution and the disclosure made

—facilitating competition by restricting the ability of the patentee to prohibit others from building on or designing around patented inventions

—providing extensive safeguards to ensure that patent rights are not exploited inappropriately.58

While the criteria of patentability enshrined in section 3(d) may not be sufficiently clear for the patent applicant, great expectations seem to have been placed on this provision. According to TC James:

Patenting becomes one such strategy and many companies seek to increase [the] number of patents on a single product as part of this strategy, mainly to keep off competition. Even without intellectual property protection, originator companies have an advantage over the generic pharma companies as they can bring their products to the market much before the latter and that gives them strong market presence by the time others enter. Generics serve a major public health cause by introducing cheaper drugs compared to the patented ones. Removal of Section 3(d) will result in evergreening and delay in the entry of generics thereby adversely affecting public health.59

The TC James Report asserts that IPR standards should depend on the stage of development:

Patent protection . . . gives a virtual monopoly for a period of 20 years. During this period no competition, including independent invention, is allowed. Therefore, extension of such a monopoly needs to be viewed seriously, particularly where it affects public interest such as public health. In the matter of intellectual property laws, [a] one size fits all approach is neither right nor in the interest of humanity. Stage of development of a country has to be borne in mind while prescribing patent standards.60

B Patentability of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Inventions

There are different forms of substances in the chemical field, such as new chemical compounds (or new chemical entities (NCE)), new compositions or derivatives. Chemical derivatives have different structures, to which certain properties and sometimes advantages in their usage can be attributed. For example, crystal forms often increase stability against changes in temperature, and polymorphs are easier for synthesis or isolation and could thus reduce manufacturing costs. Medicinal use (therapeutic efficacy) could be considered as contributing to the patentability of a substance. Derivatives of a compound are relatively easily invented, because they are obtained in a relatively conventional way. Solid salts tend to have no inventive step. Advantageous effect sometimes increases the patentability of crystals and other derivatives. As these changes of chemical characteristics may reflect relatively minor innovation, the novelty and inventive step of medicinal use is strictly examined in a rigorous system. Section 3(d) of the Indian Patents Act 2005 emphasises that, for derivatives to be considered ‘inventions’, they must have sufficiently enhanced ‘efficacy’ in comparison to the known compound. For example, the polymorphic forms A and B of an organic compound may differ in their solubilities in water and their crystallisation behaviour, but the novelty of such forms may not be recognised, unless they differ significantly in properties with regard to efficacy.61 The salient characteristic of section 3(d) is that its Explanation emphasises the question of whether a compound must be considered different from a known compound in order for its patentability to be recognised.

The Indian Patent Office (IPO) explains that section 3(d) is a simple clarification adapted to chemical and pharmaceutical inventions.62 However, Section 3(d) clearly rejects patentability of a new use of a known substance and therefore is not a simple explanation of how the Indian Patents Act recognises novelty, inventive step and industrial applicability. In most countries, the novelty of the claimed medicinal invention is not denied when it and the cited invention differ in medicinal use; and if an advantageous effect compared with the cited invention cannot be foreseen by a person skilled in the art from the state of the art, the claimed medicinal invention is considered to involve an inventive step (see chapters 1 and 3).

The derivatives may have advantageous effects both in chemical properties (such as stability, better conservation conditions) or therapeutic effects (such as enhanced curative effects, reduced side-effects) or both. Therapeutic effects are proven often as a result of clinical studies which have not yet been effectuated at the time of patent filing. Specific forms of derivatives by themselves do not indicate whether or not they are patentable, and the eligibility of the proposed invention is determined by the proper application of patentability criteria (novel and having inventive step and industrial applicability). Normally, under most patent laws of developed countries, the novelty of the claimed medicinal invention is not denied when the compound, having a specific attribute of the claimed medicinal invention, differs from the compounds of a cited invention.

Many derivatives have predictable properties and their patentability is decided case by case. Among the developed country patent offices, some may have slightly higher criteria of judgment, mainly because of court decisions. For example, the EPO’s standards concerning isomers may be slightly higher than those of other jurisdictions.63 New compounds can be close to the prior art when the new compound is an optically active enantiomer of a compound previously known only in a racemic form.64 It can therefore be argued that the optically active form cannot be regarded as novel, if the racemate is known.65 Still, the EPO considered in Hoechst/Enantiomers that optical isomers of known racemates are novel per se,66 and that the patentability of the optical isomers is rather a question of inventive step. Despite some differences in the examination standards among the US, Europe and Japan, the positive attitude towards finding patentability is common, which differs from the perspective that the fewer the patents, the better it is for society.

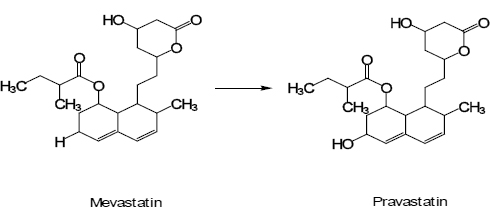

A metabolite67 is patentable if novel and inventive. Mevalotin (pravastatin sodium), an antihyperlipidemic agent that acts by inhibiting cholesterol synthesis, is a metabolite whose bio-conversion by streptomyces carbophilus gives fewer side-effects, increased solubility, and cholesterol biosynthesis inhibition several times greater than its previous compound, mevastatin (ML-236B – not commercialised).

However, there are cases where the sales of generic medicines may infringe the patent claiming the active metabolite of the original drug substance. Merrell Dow sold terfenadine, an antihistamine that had been sold world-wide. The patent-holder later obtained a separate patent on the active metabolite of the original compound and sued manufacturers of generic terfenadine in many countries after the patent expiry. In the UK, uninformative prior use cannot invalidate the patent under the Patents Act, 1977. The House of Lords held that the disclosure of the terfenadine patent specification itself, although it did not mention the active metabolite, made available to the public the invention of the acid metabolite because it enabled the public to work the invention by making the active metabolite in their livers, and invalidated the patent.68 In many other jurisdictions, the metabolite patent of this medicine did not sustain validity.69

As long as relevant patents exist, as a general rule, a third party may not manufacture or sell any pharmaceutical products protected by the patents. Under certain conditions, however, testing, such as clinical trials, for approval applications by generic drug manufacturers does not constitute infringement.

For a drug, there are patents such as basic substance patents and its derivative patents (such as compounds and salts, crystals, hydrates, solvates and intermediates), manufacturing method patents, patents for utility and for formulation of other administration methods, and use patents that describe active ingredients in a structural form or a function, or prodrugs.70 In drug discovery research, there are various types of patents related to the basic product patent, popularly called ‘umbrella patents’. These include patents on the manufacturing process and intermediates, various chemical derivatives such as salts, crystals, hydrates, solvates, formulations or methods of administration, and prodrugs, each playing specific roles in the drug development and marketing strategy. Many of these umbrella patents, variants of the same compound (molecule) could be minor. On the other hand, they may indeed be used as means to stop generic entry.

By comparison, what are popularly called ‘me-too’ drugs are molecular variants (having different molecular structures, described decades ago as ‘molecular roulette’), and should be distinguished from ‘evergreening’. Marketing first-of-a-kind products is important in those technological fields where products are outmoded quickly, whereas in medicine, the first-in-class medicines are not necessarily the best-in-class, as newer medicines often improve upon older, in terms of side-effects or modes of administration. These follow-on drugs often compete in the same relevant market (chapters 1 and 9). Both evergreening (umbrella patents) and me-too drugs have been criticised, particularly when there is little or no therapeutic improvement in the variant. However, assumptions about ‘me-too’ drugs can be completely wrong, in that quite minor changes in the molecule can produce dramatic changes in clinical performance. This was true of beta blockers for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases in the 1960s and 70s (atenolol (Tenormin) was the ninth and then best) and in the 1980s; fluoxetine (Prozac) was a ‘me-too’ of a Swedish pioneer compound which was not launched on safety grounds. Prozac was the second, not the first-in-class. There are many other examples. In short, minor molecular variations may or may not produce therapeutic advances. At the time of patent application filings, ie, before conducting clinical studies, therapeutic advantages are often difficult to measure.

For pharmaceuticals, the protection afforded by a patent of a single basic substance (or manufacturing process) is extremely important for continuous, long-term R&D efforts (see chapter 1). In addition to the nature of the active ingredient itself, issues such as appropriate formulation technology, elution, absorbability within the body, water solubility, and combined use with other drugs, cannot be ignored. Formulation technologies can be considered patentable inventions if they are novel, having inventive step and industrially applicable. Some examples include taxol (commonly known as paclitaxel, which is a treatment method claim in the US and a formulation claim in Japan) which suppresses side-effects and leuplin (Leuprorelin), which is designed with a special release control for the active pharmaceutical ingredient71 in dosage forms for intramuscular depot injection every 1, 3 and 4 months, respectively.

The introduction of a new variant of an existing product is called a ‘line extension’. Normally, the objective of line extensions is to extend the therapeutic life of the original product by improving its effectiveness, safety or convenience for the patient and not necessarily linked to the preservation of exclusivity. However, line extensions often have that effect in practice if the new line is itself patented and is used when the original product loses patent protection (see below p 443).

C The Cost of ‘Evergreening’

i Different meanings of ‘evergreening’

Patents confer a legal monopoly over the patented technology, but not necessarily an economic monopoly of the products using this technology in the relevant markets (see chapter 1).72 In fact, most patents do not correspond to a drug on the market and, therefore, the above argument is too general. The development and marketing of pharmaceuticals are supported by a patent strategy that aims to gain a competitive edge through patent life-cycle management. Patenting is normally pro-competitive, but life-cycle management may involve particular anticompetitive behaviour or strategies specifically aimed at eliminating competitors in the relevant product market, depending on the patent or competition laws of a country.

The word ‘evergreening’ has increasingly been used, but it is not entirely clear what scope of behaviour this word covers, or whether it is a normal behaviour under the patent law or denotes some kind of abuse. The behaviour involves the act of extending exclusivity. The US decision in Fisons plc v Quigg73 stated that ‘“Evergreening” refers to the use of a series of patents issued at different times to extend the period of exclusivity of a product beyond the 17 years’.

The WHO’s Commission on Intellectual Property, Innovation and Public Health (CIPIH) in 2006 defined evergreening as ‘a term popularly used to describe patenting strategies that are intended to extend the term on the same compound’.74 According to this Report, ‘evergreening occurs when, in the absence of any apparent additional therapeutic benefits, patent holders use various strategies to extend the length of their exclusivity beyond the 20-year patent term.’75 However, the scope of ‘evergreening’ differs widely according to the person who uses the term.

Evergreening, in one common form, occurs when the brand-name manufacturer literally “stockpiles” patent protection by obtaining separate 20-year patents on multiple attributes of a single product. These patents can cover everything from aspects of the manufacturing process to tablet colour, or even a chemical produced by the body when the drug is ingested and metabolised by the patient.

The EGA notes that through patent strategies, the originator manufacturer forces generic manufacturers ‘to choose between waiting for all the patents to expire and applying for marketing authorisation anyway, running the risks of litigation and the associated costs and delays’. For the EGA, therefore, ‘evergreening’ involves not only patenting behaviour, but also a whole range of conducts to delay the entry of generic products:

. . . originator laboratories no longer wait until the end of a product’s patent life to begin the evergreening process. In order to maximise revenues from their products, pharmaceuticals executives begin preparing strategies to extend patents and stifle generic competition at the outset of product life-cycles. To evergreen their products, the originator company will develop what are euphemistically called “life-cycle management plans” composed not only of patent strategies, but an entire range of practices aimed at limiting or delaying the entry of a generic product onto the market.’77

For the EGA, ‘Though . . . most of these strategies are, in the strictest sense of the word, legal’, some represent ‘a misuse of pharmaceuticals patents and the regulations governing authorisation’. It states that ‘Evergreening is clearly anti-competitive, results in higher expenditure for Europe’s financially burdened healthcare systems, and drives up patient co-payments.’ According to the EGA, therefore, most ‘evergreening’ is anti-competitive; it is however not illegal under competition law. The EGA concludes by asserting that these ‘questionable practices’, which encompass all the conduct aimed at delaying generics, lead to ‘higher prices for patients’.

The recent EU Pharmaceutical Sector Inquiry Final Report (EU Report)78 refers to the word ‘evergreening’ mostly as it is used by generic companies, their industry associations and consumer associations. For example, the Report cites the criticisms of the Bureau Européen de l’Union des Consommateurs (BEUC), which understands evergreening as embracing a wide range of patenting:

patent strategies can constitute barriers to the entry of new generic medicines into the market. We are very much concerned by the phenomenon of so-called “evergreening”, which describes a specific tactic used by originators to extend patents by seeking to obtain as many patents as possible during the development of the product and the marketing phase, and to obtain patent extensions for new manufacturing processes, new coatings and new uses of established products . . . Originators can also slightly change an active ingredient and present an old medicine as a new product and register a new patent.79

The EU Report seems to pay particular attention to the use of the term ‘evergreening’ in explaining the so-called ‘follow-on life-cycle strategies’:

Under certain circumstances the patent strategy might also pursue a more specific objective, namely to facilitate the switch to follow-up inventions or second generation products, criticised as “evergreening” by the generics industry, which will be analysed in more detail in Chapter C.2.6. below.80

In Chapter C.2.6, the Report describes certain patent life-cycle strategies ‘to facilitate the switch to follow-up inventions or second generation products’.81 According to the EU Report, the effects of ‘research for incremental innovation for top-selling products in their portfolio to ensure further development of their products, sometimes lead to “second generation products”’, with the result that ‘the new products show little or limited innovation but which serve[s] primarily to retain the revenue streams of the first generation product.’82 Thus, the EU Report calls those patents (variations on the same molecules) ‘secondary patents’. On the other hand, the Report rightly distinguishes umbrella patents from ‘follow-on product patents’, or ‘second generation drugs’, and considers these practices to be a type of patent life-cycle strategy. Astrazeneca’s Losec (omeprazole; Prilosec in the US) case was the European Commission’s first abuse of dominance enforcement case83 in the pharmaceutical sector, in 2005. According to the European Commission’s Decision on this case, one of the abuses in the meaning of Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) is the selective deregistration by Astrazeneca (of Losec capsules and/or the launch of Losec tablets) which removed the reference market authorisation on which generic firms and parallel traders arguably needed to rely to enter and/or remain on the market in Denmark, Norway and Sweden.84

The EU Pharmaceutical Sector Report further elaborates on the strategies of originator companies in launching the ‘second generation drugs’ by the use not only of patents and drug regulatory rules85 but also by the use of doctors’ recommendations and promotion of information. The EU Report claims that this makes it difficult for generics to enter:

generic companies felt that in this manner originator companies could succeed in “evergreening” their blockbuster medicines well beyond the protection period of the patent covering the active ingredient of the previously marketed product.86