Trespass to the Person

13

Trespass to the person

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

■ Understand the basic origins and character of trespass to the person

■ Understand the elements that are common to all forms of the tort

■ Understand the definition of and essential elements for proving assault

■ Understand the definition of and essential elements for proving battery

■ Understand the definition of and essential elements for proving false imprisonment

■ Understand the definition of and essential elements for proving an action for intentional indirect harm under Wilkinson v Downton

■ Understand the basis of liability under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997

■ Critically analyse each tort

■ Apply the law to factual situations and reach conclusions

13.1 The origins and character of trespass

13.1.1 Historical origins

Trespass was one of the two original forms of action (see Chapter 1.1). The term has survived to the present day in the context of specific torts, one being trespass to the person. The essence of all modern forms of trespass can be found in the old idea that trespass was the appropriate remedy for any direct and forcible injury. As will be seen, trespass to the person relates to direct and forcible injury to the person. Before turning to the tort itself it is necessary to consider the legal meaning of:

■ direct

■ forcible and

■ injury.

13.1.2 Direct

The traditional explanation of this word is that the injury must follow so closely on the act that it can be seen as part of the act. This is still true but perhaps implies that injuries caused by a car accident are also direct which is not legally the case. Such injuries are regarded as consequential. (For a more detailed discussion of this point see Chapter 4.2.) As Lord Denning explained:

QUOTATION

‘we divide the causes of action now according as the defendant did the injury intentionally or unintentionally. If one man intentionally applies force directly to another, the plaintiff has a cause of action in … trespass to the person…. If he does not inflict injury intentionally, but only unintentionally, the plaintiff has no cause of action today in trespass. His only cause of action is in negligence.’

Letangv Cooper [1964] 2 All ER 929, CA

This difficult proposition is easier to understand when the facts of the case are considered.

CASE EXAMPLE

Letang v Cooper [1964] 2 All ER 929, CA

While on holiday in Cornwall, Mrs Letang was sunbathing on a piece of grass where cars were parked. While she was lying there, Mr Cooper drove into the car park. He did not see her. The car went over Mrs Letang’s legs injuring her. She claimed damages on the basis of both negligence and trespass to the person. It was agreed by both sides that the action in negligence was statute-barred, i.e. the action had not been commenced within the requisite three-year time limit. The question was therefore whether or not her claim could succeed in trespass to the person where the time limit of six years had not expired?

JUDGMENT

‘If [the action] is intentional, it is the tort of assault and battery. If negligent and causing damage, it is the tort of negligence … [The plaintiff’s] only cause of action here … (where the damage was unintentional), was negligence and not trespass to the person.’

Lord Denning

The definitions of each of the three component parts of trespass to the person incorporate the word intentional as well as direct. The old meaning must, however, be understood if the rest of the law is to make any sense! These issues are discussed in more depth in Chapter 1.

13.1.3 Forcible

While the word itself conjures up a picture of force which causes or is capable of causing physical injury, in reality the law uses the term to describe any kind of threatened or actual physical interference with the person of another. An unwanted kiss can be a trespass to the person (R v Chief Constable of Devon & Cornwall, exp CEGB [1981] 3 All ER 826).

13.1.4 Injury

Given the explanation of forcible it comes as no surprise to learn that injury is interpreted widely and can include any infringement of personal dignity or bodily integrity. Actual physical harm is not an essential ingredient of trespass to the person although in many cases it may have occurred. The tort is actionable per se. In other words it is not necessary to prove actual damage. It is only necessary to prove that the actions of the defendant fulfil the requisite criteria.

13.1.5 The tort

Trespass to the person has three components which may occur together or separately. Each of itself gives rise to a cause of action. The components are:

■ assault

■ battery

■ false imprisonment.

Assault and battery will each be defined and explained, the defences applicable to both these torts being considered together. False imprisonment will then be considered separately.

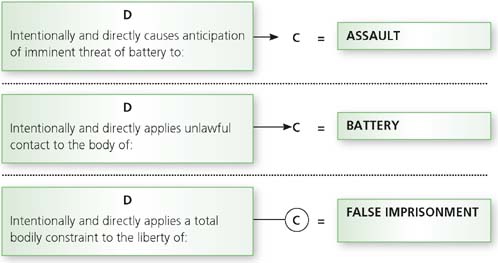

Trespass to the person can be committed in one of three ways (see Figure 13.1).

13.2 Assault

13.2.1 Definition

The tort can be defined in various ways. For example:

■ ‘The act of putting another person in reasonable fear or apprehension of an immediate battery by means of an act amounting to an attempt or threat to commit a battery amounts to an actionable assaulf (REV Heuston and R A Buckley, Salmond and Heuston on the Law of Torts (20th edn, Sweet & Maxwell, 1992), p. 127).

■ ‘Assault is an act of the defendant which causes the claimant reasonable apprehension of the infliction of a battery on him by the defendant’ (W V H Rogers, Winfield and Jolowicz on Tort (16th edn, Sweet & Maxwell, 2002), p. 71).

■ ‘An assault is an act which causes another person to apprehend the infliction of immediate, unlawful, force on his person’ (Goff LJ in Collins v Wilcock [1984] 3 All ER 374).

13.2.2 Ingredients of the tort

Direct and intentional

The words direct and intentional have the meaning discussed in section 13.1.

Conduct

Conduct in this context amounts to something which threatens the use of unlawful force. An obvious example is shaking a fist under someone’s nose causing them to fear that they are about to be punched. In most cases it may be true that the assailant’s actions clearly convey the necessary threat, but this is not always so.

In the modern world threats can be conveyed in many ways. Apart from physical action, the most obvious way is by means of a verbal threat. Traditionally, the use of threatening words alone could not amount to an assault (R v Meade and Belt [1823] 1 Lew CC184). This may have been satisfactory in 1823 but in the twenty-first century there are other means of communication, for example by telephone and email. To the victim a verbal threat by these means may be just as credible as a gesture supported by threatening words. In criminal cases there has been recognition that words alone can indeed amount to an assault. In R v Ireland [1997] 4 All ER 225 the House of Lords held that silent telephone calls, sometimes accompanied by heavy breathing, could amount to a criminal assault. Lord Steyn, rejecting the proposition in R v Meade and Belt, said:

JUDGMENT

‘The proposition … that words can never suffice, is unrealistic and indefensible. There is no reason why something said should be incapable of causing an apprehension of immediate personal violence … Take now the case of the silent caller. He intends by his silence to cause fear and he is so understood. The victim is assailed by uncertainty about his intentions. Fear may dominate her emotions … She may fear the possibility of immediate personal violence. As a matter of law the caller may be guilty of an assault.’

Words can have the opposite effect by making it clear that the assailant does not intend to carry out the threat.

CASE EXAMPLE

Turberville v Savage [1669] 1 Mod Rep 3

The assailant put his hand on his sword and said ‘If it were not assize-time, I would not take such language from you.’ The victim alleged that he had been in fear that he was about to be attacked.

The statement was in fact a declaration by the assailant that he did not intend to attack the victim because the judges were in town. The intention as well as the act makes an assault.

Reasonable fear

The victim’s fear that the threat is likely to be carried out must be reasonable. In part this depends on a subjective test which looks at the victim’s perception of the situation. In R v St George [1840] 9 C & P 483 the judge said:

JUDGMENT

‘It is an assault to point a weapon at a person, though not loaded, but so near, that if loaded, it might do injury.’

Parke B

The victim in such a case fears perfectly reasonably that he is about to be shot. If, however, the victim knew that the gun was unloaded, any fear would likely be held to be unreasonable.

It follows that the threat must be capable of being carried out at the time it is made. (In the case of telephone threats, the House of Lords in R v Ireland indicated that the fear should be that the assailant would be likely to turn up ‘within a minute or two’.) What, however, would be the position if the defendant was to be prevented from carrying out the threat?

CASE EXAMPLE

Stephens v Myers [1830] 4 C & P 349

The claimant was acting as chair at a parish meeting and was seated at some distance from the defendant with other people seated between them. The meeting became angry and a majority decision was taken to expel the defendant. He said that he would rather pull the claimant out of the chair than be expelled and went towards him with a clenched fist. The defendant was stopped by other people before he was close enough actually to hit the claimant. The general opinion of others present was that the defendant would have hit the claimant had he not been stopped before he could do so.

It is clear that Mr Stephens’ perception that he was about to be hit was reasonable; at the time it was made, Mr Myers was in a position to carry it out. Where the assailant is not in such a position, the outcome may be different.

JUDGMENT

‘if he was advancing with that intent, I think it amounts to an assault in law. If he was so advancing, that, within a second or two of time, he would have reached the plaintiff, it seems to me that it is an assault in law.’

Tindal CJ

CASE EXAMPLE

Thomas v National Union of Mineworkers (South Wales Area) [1985] 2 All ER 1

The claimant was a miner who continued to work during a particularly bitter strike by members of the NUM. The claimant and colleagues were bussed into work through a large crowd of striking miners who made threatening gestures and shouted threats at those on the bus.

For liability for assault to occur, there had to be the ability to carry out the threat at the time it was made. The crowd was kept away from the claimant and the others by a large number of police officers. They were also protected by being on a moving bus.

It seems therefore that ability to carry out the threat must exist at the time the threat is made. It has been seen, however, that this rule has been somewhat relaxed in the area of criminal law (R v Ireland). Whether this will enable the courts to devise an effective remedy for threats conveyed via email or the use of other technology remains to be seen. Abusive and threatening emails and text messages are being reported by the media as part of the growing problem of bullying in schools and the workplace. Perhaps it will not be long before this area of the law is reconsidered.

13.3 Battery

13.3.1 Definitions

Different definitions can be found in different sources. Thus:

■ ‘Battery is the intentional and direct application of force to another person’ (W V H Rogers, Winfield and Jolowicz on Tort (16th edn, Sweet & Maxwell, 2002), p. 71).

■ ‘The application of force to the person of another without lawful justification’ (REV Heuston and R A Buckley, Salmond and Heuston on the Law of Torts (20th edn, Sweet & Maxwell, 1992), p. 125).

■ ‘Battery is the actual infliction of unlawful force on another person’ (Goff LJ in Collins v Wilcock).

The problem is that none of these definitions covers all the requisite elements for liability. A better definition is here the defendant, intending the result and without lawful justification or the consent of the claimant, does an act which directly and physically affects the person of the claimant.

13.3.2 Ingredients of the tort

Intention

Life would be intolerable and the courts would be overloaded if every touch we received while going about our daily business was actionable. It is clear that the touching must be intentional if there is to be liability for battery, while non-intentional touching may amount to negligence. (See Letang v Cooper in section 13.1.2.) It must be remembered that it is the touching which must be intentional; it does not matter whether or not the defendant intended to cause injury although this may be relevant to the element of hostility discussed later in this section.

A problem can arise where the defendant intends to hit one person but misses and hits someone else. In such cases the doctrine of ‘transferred malice’ comes into play. The intention was to hit someone; the fact that the actual person hit was not the intended target is irrelevant.

CASE EXAMPLE

Livingstone v Ministry of Defence [1984] NI 356, NICA

A soldier in Northern Ireland fired a baton round targeting a rioter. He missed and hit the claimant instead. It was held that the soldier had intentionally applied force to the claimant.

Direct

The battery must be the direct result of the defendant’s intentional act. This is easily seen when a punch or other form of physical touching occurs.

Case law dating back over the centuries shows just how widely the courts are prepared to stretch the meaning of direct.

CASE EXAMPLE

Gibbons v Pepper [1695] 1 Ld Raym 38

The defendant whipped a horse so that it bolted and ran down the claimant. The defendant was liable in battery for the claimant’s injuries.

CASE EXAMPLE

Scott v Shepherd [1773] 2 Wm Bl 892

Shepherd threw a lighted squib into a market house. It landed on the stall of a ginger bread seller. To prevent damage to the stall, Willis picked it up and threw it across the market. Ryal, to save his own stall, picked it up and threw it away. It struck the claimant in the face and exploded, blinding him in one eye.

The defendant intended to scare someone although he did not intend to hurt the particular person who was actually injured. He was liable in battery, Willis and Ryal being held to be Shepherd’s ‘instruments’.

QUOTATION

‘the law insists, and insists quite rightly, that fools and mischievous persons must answer for consequences which common sense would unhesitatingly attribute to their wrongdoing’.

WVH Rogers, Winfield and Jolowicz on Tort (16th edn. Sweet & Maxwell, 2002), p. 235

CASE EXAMPLE

Pursell v Horn [1838] 8 A & E 602

The defendant threw water over the claimant. The force applied does not have to be personal contact and the defendant was liable in battery.

CASE EXAMPLE

Nash v Sheen [1955] CLY3726

The claimant had gone to the defendant’s hairdressing salon where she was to receive a ‘permanent wave’. A tone rinse was applied to her hair, without her agreement, causing a skin reaction. The defendant was liable in battery.

Although, as the cases illustrate, the courts have been prepared to take a fairly wide view of what amounts to a direct touching, the one thing that does appear to be clear is that only a positive act will suffice. There is unlikely to be liability in battery for an omission.

CASE EXAMPLE

Innes v Wylie [1844] 1 Car & Kir 257

A policeman stood and blocked the claimant’s entrance to a meeting of a Society from which the claimant had been banned.

JUDGMENT

‘If the policeman was entirely passive like a door or a wall put to prevent the [claimant] from entering the room, and simply obstructing the entrance of the claimant, no assault has been committed on the claimant’.

Denman CJ

Touching

Originally any touch however slight would amount to a battery. In Cole v Turner [1704] 6 Mod Rep 149 this appeared to have been qualified by Lord Holt when he said that ‘the least touching in anger is a battery’. Does this mean that the touching, in addition to being intentional, must also be hostile?

Goff LJ, in Collins v Wilcock [1984] 3 All ER 374 (for facts see section 13.4.1), stated that ‘the fundamental principle, plain and incontestable, is that every person’s body is inviolate’. He went on to expound this by quoting from Blockstone’s Commentaries in which Blackstone explained that the law cannot draw the line between different degrees of violence, and therefore totally prohibits the first and lowest stage of it; every man’s person being sacred, and no other having a right to meddle with it, in any the slightest manner.

Goff LJ explained: ‘a broader exception has been created … embracing all physical contact which is generally acceptable in the ordinary conduct of daily life’. While it may be a matter of personal opinion as to what constitutes generally acceptable conduct, it is clear from the judgment that actions such as tapping someone on the shoulder to gain their attention would not amount to a battery.

CASE EXAMPLE

Wilson v Pringle [1986] 2 All ER 440

A schoolboy admitted that he had pulled a bag which was over the shoulder of another boy. The other boy fell over and was injured. Summary judgment on the basis of battery was entered for the claimant, the defendant eventually appealing to the Court of Appeal.

JUDGMENT

‘It is not practicable to define a battery as “physical contact which is not generally acceptable in the ordinary conduct of daily life.” In our view … there must be an intentional touching or contact in one form or another of the [claimant] by the defendant. That touching must be proved to be a hostile touching … Hostility cannot be equated with ill-will or malevolence. It cannot be governed by the obvious intention shown in acts like punching, stabbing or shooting. It cannot be solely governed by an expressed intention, although that may be strong evidence. But the element of hostility … must be a question of fact… It may be imported from the circumstances.’

Croom-Johnson LJ

In the event, the schoolboy’s act of pulling the bag was merely a prank, the necessary element of hostility was lacking.

Wilson v Pringle created more questions than answers. The explanation given is not entirely helpful. It is still necessary to ask ‘what does hostility mean?’ The question was partially answered in R v Brown [1994] 2 All ER 75.

CASE EXAMPLE

R v Brown [1994] 2 All ER 75

The case concerned a group of sado-masochistic homosexuals who willingly cooperated in the commission of acts of violence against each other for sexual pleasure. The men were prosecuted for malicious wounding contrary to s20 Offences Against the Person Act 1861. The equivalent civil action would be based in battery. Following their conviction, the case reached the House of Lords where one of the issues considered was whether or not hostility on the part of the inflictor of an injury was an essential ingredient for battery.

Having seemingly approved the view in Collins v Wilcock that hostility could not be equated with ill-will or malevolence, Lord Jauncey went on to say that if the appellants’ actions:

JUDGMENT

‘were unlawful they were also hostile and a necessary ingredient of [malicious wounding] was present’.

It seems therefore that if the touching is unlawful, then it is hostile. As will be seen in the next part of this chapter, lawful authority in a variety of forms is a full defence to the tort. R v Brown, although a criminal case, appears to go some way to providing an explanation of when a touching will be regarded as hostile.

The question remains, however – is a hostile intent necessary in order to establish liability? Where does this leave medical treatment which has been given against the wishes of a patient? Doctors after all act with the intention of doing good for their patients. The issues raised by medical cases will be discussed in the next part of this chapter.

13.4 Defences to assault and battery

These are dealt with in one section as the same defences are available to each tort.

13.4.1 Lawful authority

If a person committing assault and/or battery has legal authority for the action, there can be no liability for that act. Statute gives two groups such authority.

Police officers

The powers of police officers are found in statute and, provided an officer acts within the scope of those powers, there can be no complaint for trespass to the person. If, however, the action goes beyond what is permitted, a police officer may be liable in the civil courts in the same way as any other person.

CASE EXAMPLE

Collins v Wilcock [1984] 3 All ER 374

A police officer needed to obtain a woman’s name and address in order to caution her for soliciting for the purpose of prostitution. The officer detained the woman by holding her by the elbow. The woman scratched the police officer and was charged with assaulting a con-stable in the execution of her duty. The question was whether the police officer was acting lawfully when she held the woman’s elbow to detain her.

JUDGMENT

‘The fact is that the [police officer] took hold of the [woman] by the left arm in order to restrain her. In so acting she was not proceeding to arrest the [woman]; and since her action went beyond the generally acceptable conduct of touching a person to engage his or her attention, it must follow … that her action constituted a battery on the [woman], and was therefore unlawful.’

Goff LJ

Reasonable force may be used to make an arrest (Criminal Justice Act 1967 s3). What is reasonable depends on the facts. The general rule is that the force must be proportionate to the crime being prevented. The use of lethal force will seldom be necessary and might be thought to be a breach of Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights. In McCann, Farrell and Savage v UK [1995] 21 EHRR 97, ECtHR, arising from the deaths of three IRA suspects killed by members of the SAS in Gibraltar, it was accepted that lethal force can be used provided it is reasonably justifiable.

Health professionals treating people with mental illness

The Mental Health Act 1983 permits treatment for mental disorder to be given to patients who have been compulsorily detained using powers granted by the Act. By s63, treatment may be given without the consent of the patient, the Act including additional safeguards for extreme treatment such as psychosurgery and electro-convulsive therapy. Treatment otherwise than for the mental disorder is governed by the same rules which protect people who do not suffer from mental disorder.

13.4.2 Consent

If the claimant consents to the actions of the defendant, the claimant has no cause of action. Consent may be express or implied. It can be argued that there is implied consent to the jostling which occurs in a packed train during the rush-hour.

Sport

A person who takes part in a contact sport such as soccer, rugby or boxing, consents to the touching that occurs when the sport is played according to the rules.

CASE EXAMPLE

Simms v Leigh Rugby Football Club [1969] 2 All ER 923

A broken leg resulted from a tackle during a rugby game.

By voluntarily taking part in a contact sport, players consent to touching which occurs provided it is within the rules of the game. In this case the tackle had been lawful therefore no battery had occurred.

If the touching is not permitted within the rules of the sport, then it is unlawful. The victim has not consented and the assailant may be liable for trespass to the person.