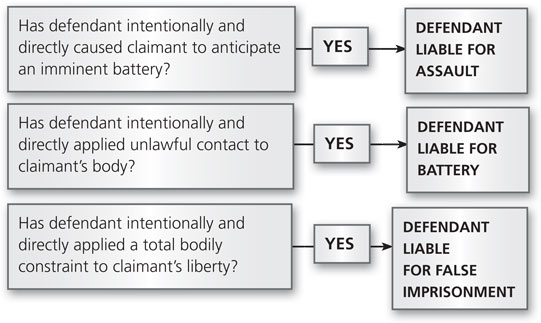

Trespass to the person

Trespass to the Person

8.1.1 Definitions

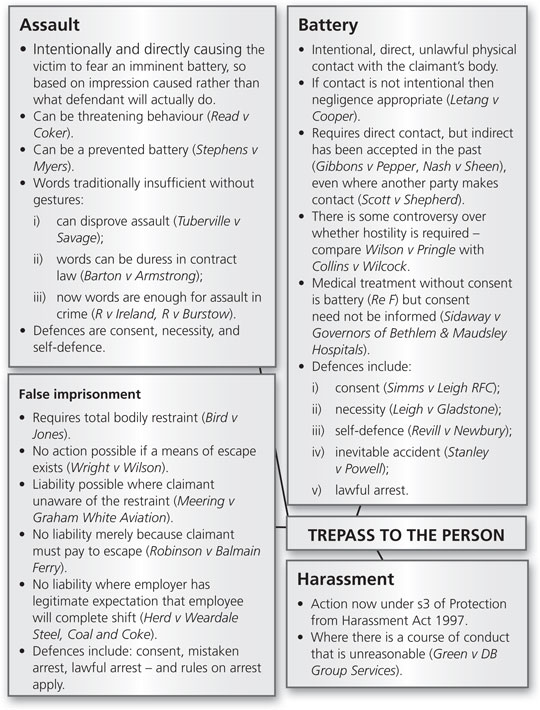

1. The old view was that assault was an incomplete battery.

2. Modern definition is intentionally and directly causing a person to fear being victim of an imminent battery (Letang v Cooper (1965)).

8.1.2 Ingredients of the Tort

1. Assault is free-standing, so intention refers to the impression it will produce in claimant, not as to what defendant intends to do. Compare R v St. George (1840) with Blake v Barnard (1840).

2. No harm or contact is required (I de S et Ux v W de S (1348)).

3. Requires active behaviour, so merely barring entry is no assault (Innes v Wylie (1844)).

4. However, threatening behaviour can be assault (Read v Coker (1853)).

5. An attempt to commit a battery which is thwarted is still an assault (Stephens v Myers (1830)).

6. Traditionally words alone were not an assault:

but could disprove an assault (Tuberville v Savage (1669));

but could disprove an assault (Tuberville v Savage (1669));

and a threat on its own can be assault (Read v Coker);

and a threat on its own can be assault (Read v Coker);

and in contract law, words can amount to duress if the threat is sufficiently serious (Barton v Armstrong (1969));

and in contract law, words can amount to duress if the threat is sufficiently serious (Barton v Armstrong (1969));

more recently, in crime, words alone and even silence have been accepted as assault (R v Ireland; R v Burstow (1998)).

more recently, in crime, words alone and even silence have been accepted as assault (R v Ireland; R v Burstow (1998)).

7. The claimant must be fearful of an impending battery. Compare Smith v Superintendent of Woking (1983) with R v Martin (1881).

8.1.3 Defences

1. Consent (as in sports).

2. Self-defence (e.g. threatening an attacker).

3. Necessity (frightening people away from possible harm).

8.2.1 Definitions

There are a number of possible definitions:

the defendant intentionally and directly applies unlawful force to claimant’s body – but force is irrelevant in, for example, medicine;

the defendant intentionally and directly applies unlawful force to claimant’s body – but force is irrelevant in, for example, medicine;

the defendant, intending the result, does an act which directly and physically affects the claimant, but still implies damage;

the defendant, intending the result, does an act which directly and physically affects the claimant, but still implies damage;

has been said to include the ‘ordinary collisions of life’, but this is very unlikely (Wilson v Pringle (1987)).

has been said to include the ‘ordinary collisions of life’, but this is very unlikely (Wilson v Pringle (1987)).

8.2.2 Ingredients of the Tort

1. Intention is a fairly recent requirement – without it an action should be brought in negligence (Fowler v Lanning (1959)).

2. Traditional distinction was between direct and indirect contact:

but now between intention and negligence (Letang v Cooper (1965));

but now between intention and negligence (Letang v Cooper (1965));

although in traditional cases indirect damage was often accepted (Gibbons v Pepper (1695));

although in traditional cases indirect damage was often accepted (Gibbons v Pepper (1695));

often where negligence might have seemed more appropriate (Nash v Sheen (1953));

often where negligence might have seemed more appropriate (Nash v Sheen (1953));

and even where other parties have actually caused the harm (Scott v Shepherd (1773)).

and even where other parties have actually caused the harm (Scott v Shepherd (1773)).

3. Usually no liability for omissions in trespass, only positive acts (Fagan v Metropolitan Police Commissioner(1969)).

4. Hostility is a recent requirement, with traditional foundations:

Lord Holt CJ in Cole v Turner (1704) suggested that ‘the least touching of another in anger is a battery …’;

Lord Holt CJ in Cole v Turner (1704) suggested that ‘the least touching of another in anger is a battery …’;

restated in Wilson v Pringle (1987);

restated in Wilson v Pringle (1987);

but conflicting with Lord Goff’s test in Collins v Wilcock (1987) of whether the contact is acceptable in the conduct of daily life.

but conflicting with Lord Goff’s test in Collins v Wilcock (1987) of whether the contact is acceptable in the conduct of daily life.

5. Medical treatment without consent has always been battery: