Torts Relating to Goods

12

Torts relating to goods

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

■ Understand the common law basis for liability for defective products

■ Understand the statutory basis for liability for defective products

■ Understand the bases of liability for interference with goods

■ Critically analyse each tort

■ Apply the law to factual situations and reach conclusions as to liability

This chapter is divided into three sections. First, liability for defective products under common law and, second, under statute. The third section deals with liability for torts committed against goods.

12.1 Common law liability for defective products

12.1.1 Introduction

This area of law is partly dealt with by contract and consumer law and partly by torts, with a substantial contribution from statute. It is not appropriate to consider contract and consumer law in depth in a book on torts but it will be considered briefy. For detailed discussion reference should be made to texts relevant to the specific area such as C Turner, Unlocking Contract Law (2nd edn, Hodder Education, 2007).

12.1.2 Liability in contract and consumer law

From the nineteenth century onwards, the courts have been concerned to prevent large businesses from taking advantage of their strength to ‘bully’ consumers. Consumers were first protected by the Sale of Goods Act 1893. Protection is now found in the Sale of Goods Act 1979 as amended by the Sale and Supply of Goods Act 1994. The Act works by implying certain terms into all contracts for the sale of goods. An example is the requirement that the goods be ‘ft for their purpose’ (s14) which is not, however, implied into a private sale. Fitness for purpose includes a requirement that the goods should be free of defects and safe in normal use. People who are injured by goods which they have purchased have a remedy for breach of the term implied into the contract. Protection was extended by the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 which imposed strict limitations on the extent to which a business could exclude liability for defective products by means of an exclusion or limitation clause.

Where there is liability under the Sale of Goods Act, it is strict liability so far as the seller of the product is concerned. The buyer is entitled to be repaid the purchase price of the goods and to be compensated for further damage (but see a text on contract law for the rules relating to remoteness of damage).

It sounds as if all situations are covered but there is one fundamental flaw – only a party to a contract can generally sue for breach of that contract. This means that a person injured by a product received as a gift cannot claim using the Sale of Goods Act. This is the doctrine of privity of contract. The Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 has recently come into effect whereby a third party can have rights under the contract between the buyer and seller of the products but only provided certain conditions are fulfilled. It is not likely that this will provide an effective remedy in many cases.

What then are the rights of a person injured by a defective product who is not the buyer of that product?

12.1.3 Liability in negligence

Liability for loss or damage caused by defective products is usually accepted as starting in 1932. However, in more limited form there are much older examples.

CASE EXAMPLE

Dixon v Bell [1816] 5 M & S 198

A master handed a gun to his young servant who had no experience of handling guns. The boy was injured when the gun went off. It was accepted that the goods were potentially dangerous and ‘capable of doing mischief’ so there was held to be liability for the injuries caused by putting dangerous and defective goods in circulation.

As was seen in Chapter 2, the case of Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562 gave rise to two rules:

(i) the neighbour test which was intended to apply in all cases (the so- called ‘wide rule’); and

(ii) the principle that a manufacturer owes a duty of care to the consumer (the so- called ‘narrow rule’).

The narrow rule was explained by Lord Macmillan when he said:

QUOTATION

‘a person who engages in … manufacturing articles of food and drink intended for consumption by a member of the public in the form in which he issues them is under a duty to take care in the manufacture of those articles. That duty … he owes to those whom he intends to consume his products.’

It has been clear since 1932 that a manufacturer owes a duty of care to the ultimate consumer where products reach the consumer in much the same form as they left the factory.

QUOTATION

‘a manufacturer of products which he sells in such form as to show that he intends them to reach the ultimate consumer in the form in which they left him with no reasonable possibility of intermediate examination, and with the knowledge that the absence of reasonable care in the preparation or putting up of the products will result in an injury to the consumer’s life or property, owes a duty to the consumer to take reasonable care.’

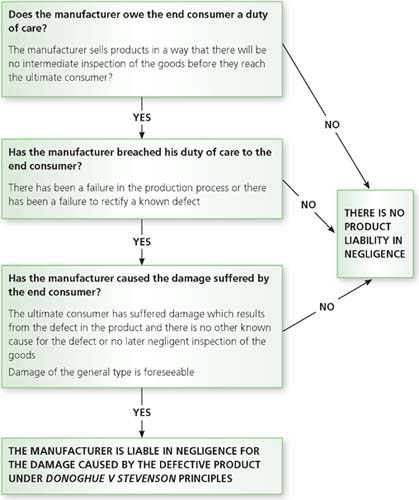

So essentially there are three key elements that must be proved for a successful claim for product liability in negligence:

■ the goods must reach the consumer and be intended to reach the consumer in the same form in which they left the manufacturer;

■ there is no possibility of an examination of or interference with the goods between leaving the manufacturer and reaching the end consumer;

■ the manufacturer knows that failing to take sufficient care of the goods may put the consumer at risk of foreseeable harm.

12.1.4 The scope of liability

Product liability in negligence concerns damage caused by or losses arising from the defect in the goods. Claims for replacement goods are made in contract law usually under the Sale of Goods Act 1979.

Originally product liability in negligence was restricted to foodstuffs but this has subsequently been extended to cover the full range of products. For instance it has included:

■ a range of manufactured consumer durables – in Grant v Australian Knitting Mills Ltd [1936] AC 85 woollen underpants contained a chemical which caused the consumer to develop dermatitis, a painful skin disease; in Herschtal v Stewart and Arden Ltd [1940] 1 KB 155 it included a defective motor car;

■ defects in a house, which can also include the fixtures and fittings (Batty v Metropolitan Property Realisations Ltd [1978] QB 554);

■ defective repair to a lift which then caused injury (Haseldine v Daw & Son Ltd [1941] 2 KB 343);

■ more recently it has included computer software (St Albans City and District Council v International Computers Ltd [1996] 4 All ER 481).

12.1.5 Bringing a claim in negligence for damage caused by defective products

Product liability in negligence relies on proving the same essential elements as for claims in negligence generally: the existence of a duty of care owed by the manufacturer to the ‘ultimate consumer’ of the product; breach of duty by the manufacturer; foreseeable damage caused by the defendant’s breach of duty.

Duty of care

The duty of care only applies in respect of goods reaching the consumer in the same form that they left the manufacturer where there is no chance of an intermediate examination.

Breach of duty

A breach of the duty by the manufacturer will generally involve a failure in the production process or alternatively a failure to rectify a known defect before the product reaches the consumer. So this may include:

■ failing to check products that have been exposed to chemicals during the manufacturing process that then may cause harm (Grant v Australian Knitting Mills Ltd [1936]);

■ failing to remedy a known fault, which may include failing to recall defective products in sufficient time to avoid harm to the consumer (Walton v British Leyland Ltd [1978], The Times, 13 July).

Foreseeable damage caused by the defendant’s breach of duty

The consumer can only recover compensation by proving that the damage was actually caused by the defect in the goods. If there is another possible cause of the damage then the consumer is unlikely to gain compensation.

12.1.6 Potential claimants

The original description in Donoghue v Stevenson given to those able to sue a manufacturer for damage caused by defective goods was ‘ultimate consumers’ or ‘end users’. On the basis that the case exploded the so- called ‘privity fallacy’ of Winterbottom v Wright [1842] 10 M & W 109 it was inevitable that Lord Atkin would produce a description that was sufficiently broad to cover people who had not bought the goods themselves.

In any case, applying the neighbour principle, a claimant is anybody that the manufacturer ‘should have in his contemplation’ as being likely to be harmed if the goods are defective. So over time the defnition has been broadened to include other situations involving foreseeable harm:

■ suppliers that are injured because of the defect in the goods – in Barnett v H and J Packer & Co [1940] 3 All ER 575 sharp metal protruding from a sweet injured a shopkeeper who was storing the sweets and the manufacturer was liable for the injury;

■ bystanders – in Stennet v Hancock and Peters [1939] 2 All ER 578 a pedestrian was injured by a component that had been negligently reassembled by a garage and which then fell off a lorry.

12.1.7 Potential defendants

The original defendant in common law product liability was limited to the manufacturer of the defective goods. However, over time the law has expanded to include a wider range of potential defendants, including a number in the chain of production and distribution where they have a potential impact on the safety of the goods:

■ wholesalers (Watson v Buckley, Osborne Garrett & Co Ltd [1940] 1 All ER 174);

■ retailers (Kubach v Hollands [1937] 3 All ER 907);

■ other suppliers of goods (e.g. through mail order) (Herschtal v Stewart and Arden Ltd [1940] 1 KB 155) – but only when the duty owed by the supplier goes beyond distributing the goods and requires that the goods are inspected;

■ people who repair goods (Haseldine v CA Daw & Son Ltd [1941] 2 KB 343);

■ people who assemble goods (Malfroot v Noxal Ltd [1935] 51 TLR 551).

The consumer has a reasonable range of potential defendants to sue as a result. However, it is a more limited range than under the Consumer Protection Act 1987.

CASE EXAMPLE

Grant v Australian Knitting Mills Ltd [1936] AC 85

The claimant purchased some woollen underwear manufactured by the defendants. The garment was contaminated by sulphites which would not normally be present. This caused the claimant to suffer severely from dermatitis.

Finding the defendant liable, Lord Wright said:

JUDGMENT

‘According to the evidence, the method of manufacture was correct, the danger of excess sulphites being left was recognised and guarded against … If excess sulphites were left in the garment, that could only be because someone was at fault…. Negligence is found as a matter of inference from the existence of the defects taken in connection with all the known circumstances.’

CASE EXAMPLE

Evans v Triplex Safety Glass Co Ltd [1938] 1 All ER 283

The claimant bought a car fitted by the makers with a windscreen of ‘Triplex Toughened Safety Glass’. While he was driving the car the windscreen shattered injuring the claimant and his passengers. Holding that the defendant was not liable Mr Justice Porter explained that an inference of fault on the part of the manufacturers could not be drawn for several reasons:

(i) the windscreen had been in place for more than a year before the accident;

(ii) the disintegration could have resulted from another cause during the course of use of the car.

It could have been badly fitted in the first place.

Unlike the cases of Donoghue v Stevenson and Grant v Australian Knitting Mills [1936] AC 85 where the cause of the problem was clear, in this case there were a number of potential causes thus fault could not be inferred.

These cases illustrate the difficulties faced by a claimant in bringing a successful action. There can be no certainty that the court will find that the defect has arisen by virtue of the defendant’s fault as it seems that the claimant has to show that all other possible causes have been eliminated.

Additional problems faced by a claimant arise from the globalisation of trade. Products are imported from all over the world. While in some cases it is theoretically possible to bring an action in negligence against a foreign manufacturer, the matter is fraught with difficulty.

12.2 Statutory liability – the Consumer Protection Act 1987

12.2.1 Background

The tort of negligence is not of much practical help in many cases. In the 1970s a number of babies were born in the United Kingdom who were seriously damaged by a drug taken by their mothers in the early stages of pregnancy for severe morning sickness. The drug, Thalidomide, was suspected of causing birth defects and was, at the time it was prescribed in the United Kingdom, banned in many countries including the United States of America. Although eventually a compensation fund for the victims was created, it took many years during which time the victims had enormous difficulty in establishing the facts of the case. This and other concerns prompted the European Union to consider creating a system which would allow consumers injured by defective products to obtain compensation more easily. Eventually Directive 85/374/EEC was created. The Preamble to the Directive states ‘liability without fault on the part of the producer is the sole means of adequately solving the problem, peculiar to our age of increasing technicality, of a fair apportionment of the risks inherent in modern technological production’.

The Directive was eventually passed into UK law by the Consumer Protection Act 1987 Part I.

12.2.2 Potential defendants under the Act

Section 2(1) of the Act states that there shall be liability ‘where any damage is caused wholly or partly by a defect in a product’.

The class of those who may be liable is spelled out in s2(2) which provides that s2(1) applies to:

SECTION

‘s2(2) (a) the producer of the product;

(b) any person who, by putting his name on the product or using a trade mark or other distinguishing mark in relation to the product, has held himself out to be the producer …;

(c) any person who has imported the product into a member State from a place outside the member States in order, in the course of … business … to supply it to another.’

The producer of the product

A ‘producer’ is obviously the manufacturer of the product but the term is expanded to include those who win or abstract non- manufactured substances, for example coal and other mined substances. It also includes those who have subjected a non- manufactured product, for example food crops, to an industrial process which has created essential characteristics of the product, for example corn fakes from corn or frozen vegetables (s1(2)).

SECTION

‘s1(3) Where an essential component fails and damage is caused, both the manufacturer of the part and the manufacturer of the defective component will be liable.’

The ‘own-brander’

The term is amplified in the Directive to include he who ‘presents himself as the producer’. The effect of this description may mean that an own- brander who clearly states that the goods are produced ‘for’ that business rather than ‘by’ that business will escape liability. It will probably apply, for example, to the supermarket chain which markets it ‘own brands’ even though the goods are produced by a manufacturer.