Torts affecting reputation

Torts Affecting Reputation

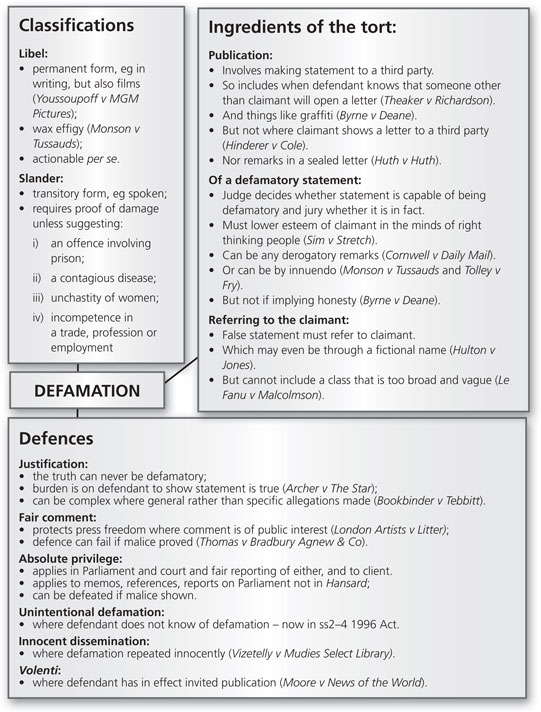

9.1.1 The Categories of Defamation

1. The main tort developed to protect reputation.

2. As such it can be made in a number of ways, but there are two specific categories: libel and slander.

3. The general distinction is between ‘permanent’ and ‘transitory’:

libel has been called a written form and slander a spoken form;

libel has been called a written form and slander a spoken form;

this view is no longer adequate because of modern technology;

this view is no longer adequate because of modern technology;

the difference owes more to origins than real justification;

the difference owes more to origins than real justification;

it has been discarded by most commonwealth jurisdictions;

it has been discarded by most commonwealth jurisdictions;

this was recommended in the UK by the Faulkes Report;

this was recommended in the UK by the Faulkes Report;

but the Defamation Act 1996 did not address this issue.

but the Defamation Act 1996 did not address this issue.

4. The two categories do have two important distinctions:

a) Libel can be crime as well as tort (R v Lemon (1977)).

b) Libel is actionable per se; for slander damage must be shown, except in four circumstances:

imputation of an offence involving imprisonment;

imputation of an offence involving imprisonment;

imputation of a contagious disease;

imputation of a contagious disease;

imputation of ‘unchastity’ of women (Slander of Women Act 1891), including lesbianism (Kerr v Kennedy (1942));

imputation of ‘unchastity’ of women (Slander of Women Act 1891), including lesbianism (Kerr v Kennedy (1942));

imputation of unfitness or incompetence in a trade, profession, office or calling (and now by Defamation Act 1952 for any employment provided claimant could be harmed as a result).

imputation of unfitness or incompetence in a trade, profession, office or calling (and now by Defamation Act 1952 for any employment provided claimant could be harmed as a result).

5. The difference between permanent and transitory is not always obvious, but there are acknowledged situations:

a written defamation is obviously libel;

a written defamation is obviously libel;

films are libels(Youssoupoff v MGM Pictures Ltd (1934));

films are libels(Youssoupoff v MGM Pictures Ltd (1934));

radio and television broadcasts are libel under the Defamation Act 1952 and the Broadcasting Act 1990;

radio and television broadcasts are libel under the Defamation Act 1952 and the Broadcasting Act 1990;

by the Theatres Act 1968 s4 a defamation in a public performance of a play is also libel;

by the Theatres Act 1968 s4 a defamation in a public performance of a play is also libel;

wax effigy in a museum is libel (Monson v Tussauds (1894));

wax effigy in a museum is libel (Monson v Tussauds (1894));

a red light hung outside a woman’s house could be libel;

a red light hung outside a woman’s house could be libel;

the spoken word in general is slander;

the spoken word in general is slander;

gestures in general are slander;

gestures in general are slander;

tapes are probably slander because they can be wiped;

tapes are probably slander because they can be wiped;

9.1.2 The Definition and Ingredients of the Tort

Definition

1. Defined as ‘the publishing of a defamatory statement which refers to the claimant and which has no lawful justification …’.

2. Each separate element of the tort must be proved.

Publication

1. This involves communicating the statement to a third party.

2. Each repeat is a fresh publication and therefore actionable, so there can be many defendants to a defamation action.

3. Publication could include:

a postcard (as it is assumed it will be seen by a third party);

a postcard (as it is assumed it will be seen by a third party);

every sale of a newspaper;

every sale of a newspaper;

every lending of a book from a library;

every lending of a book from a library;

a letter addressed to the wrong person;

a letter addressed to the wrong person;

a letter the defendant knows someone besides the claimant might open (Pullman v Hill (1891) and Theaker v Richardson (1962));

a letter the defendant knows someone besides the claimant might open (Pullman v Hill (1891) and Theaker v Richardson (1962));

graffiti that cannot be removed (Byrne v Deane (1937));

graffiti that cannot be removed (Byrne v Deane (1937));

making a remark so that it is overheard;

making a remark so that it is overheard;

the defendant can also be liable for the consequences of a defamatory statement that (s)he knows will be repeated (Slipper v BBC (1991));

the defendant can also be liable for the consequences of a defamatory statement that (s)he knows will be repeated (Slipper v BBC (1991));

it is uncertain whether repeating the remark through internal mail amounts to fresh publications.

it is uncertain whether repeating the remark through internal mail amounts to fresh publications.

4. In the following there is generally no publication:

a statement made only to the claimant who then shows it to a third party (Hinderer v Cole (1977));

a statement made only to the claimant who then shows it to a third party (Hinderer v Cole (1977));

communication between spouses only;

communication between spouses only;

a letter addressed only to the claimant;

a letter addressed only to the claimant;

remarks contained in a sealed letter (Huth v Huth (1915));

remarks contained in a sealed letter (Huth v Huth (1915));

an ‘innocent dissemination’(Vizetelly v Mudies Select Library Ltd (1900)).

an ‘innocent dissemination’(Vizetelly v Mudies Select Library Ltd (1900)).

1. Defamation trials involve a jury.

2. The judge directs the jury on the meaning of defamation.

If the judge concludes that no reasonable man could find the words defamatory (s)he withdraws the case from the jury (Capital & Counties Bank Ltd v Henty (1882)).

If the judge concludes that no reasonable man could find the words defamatory (s)he withdraws the case from the jury (Capital & Counties Bank Ltd v Henty (1882)).

If the meaning can only be defamatory the jury is so directed.

If the meaning can only be defamatory the jury is so directed.

3. If more than one defamatory meaning is alleged the judge rules which words are capable of being defamatory and which to put before the jury (Lewis v Daily Telegraph (1964)).

In Mapp v Newsgroup Newspapers Ltd (1997) CA held that the judge should evaluate the words to delimit the possible range of meanings.

In Mapp v Newsgroup Newspapers Ltd (1997) CA held that the judge should evaluate the words to delimit the possible range of meanings.

By s7 Defamation Act 1996 either party can ask before trial if words are capable of bearing a particular meaning.

By s7 Defamation Act 1996 either party can ask before trial if words are capable of bearing a particular meaning.

4. The jury then decides whether the words in fact are defamatory: ‘a statement which tends to lower the plaintiff in the minds of right-thinking members of society generally, and in particular to cause him to be regarded with feelings of hatred, contempt, ridicule, fear and disesteem …’ (Lord Atkin in Sim v Stretch (1935)).

5. So defamatory remarks depend entirely on context and include:

vulgar abuse (Cornwell v Daily Mail (1989));

vulgar abuse (Cornwell v Daily Mail (1989));

derogatory remarks(Savalas v Associated Newspapers (1976) and Roach v Newsgroup Newspapers Ltd (1992));

derogatory remarks(Savalas v Associated Newspapers (1976) and Roach v Newsgroup Newspapers Ltd (1992));

references to a person’s moral character (Stark v Sunday People (1988)).

references to a person’s moral character (Stark v Sunday People (1988)).

6. Implying honesty is not defamatory (Byrne v Deane (1937)); nor are statements that lead to sympathy rather than scorn (Grappelli v Derek Block Holdings Ltd (1981)).

7. ‘Innuendo’ can also be defamation:

so, words can defame because of their juxtaposition with other things (Monson v Tussauds (1894) and Cosmos v BBC (1976));

so, words can defame because of their juxtaposition with other things (Monson v Tussauds (1894) and Cosmos v BBC (1976));

or by containing hidden meaning (Tolley v Fry & Sons Ltd (1931) and Cassidy v Daily Mirror (1929));

or by containing hidden meaning (Tolley v Fry & Sons Ltd (1931) and Cassidy v Daily Mirror (1929));

although a complaint of such a meaning can bring other evidence into court (Allsopp v Church of England Newspaper Ltd (1972)).

although a complaint of such a meaning can bring other evidence into court (Allsopp v Church of England Newspaper Ltd (1972)).

1. The claimant must show that the statement referred to him/her:

this is easy if (s)he is named:

this is easy if (s)he is named:

it is sufficient if claimant can show people might think it refers to him/her;

it is sufficient if claimant can show people might think it refers to him/her;

this may be shown even if a fictional name is used (Hulton & Co v Jones (1910));

this may be shown even if a fictional name is used (Hulton & Co v Jones (1910));

or if two people have the same name (Newstead v London Express Newspapers Ltd (1940));

or if two people have the same name (Newstead v London Express Newspapers Ltd (1940));

or with cartoons (Tolley).

or with cartoons (Tolley).

2.