Through the Looking-Glass: A Proposal for National Reform of Australia’s Surrogacy Legislation

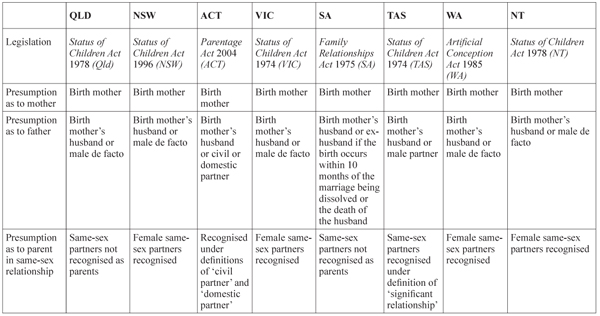

Chapter 4 Surrogacy has been the subject of intermittent academic investigation and law reform since the early 1980s.1 Notwithstanding these reforms, Australian surrogacy laws remain inconsistent. Surrogacy persists as ‘an issue with which our community continues to struggle’2 and Australia has a ‘fragmented, illogical and dysfunctional’3 surrogacy regime. For parties seeking surrogacy intrastate, interstate or internationally, the applicable legislation is often hard to identify, obscure and difficult to navigate. While there may be constitutional hurdles to overcome,4 the aim of a national model would be to bridge the legislative gaps whilst still respecting the autonomy and minimising the risk of harm for all parties involved. The purpose of this chapter is twofold: to demonstrate that the existing surrogacy regime in Australia is in need of reform and to provide a framework for a national model. Certain key aspects of current surrogacy legislation in Australia are examined in order to illustrate inconsistencies between states and territories. The chapter then develops recommendations for the framework of a national model for reform. Alice stood without speaking, looking out in all directions over the country – and a most curious country it was … ‘I declare it’s marked out just like a large chess-board!’ Alice said at last.5 Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There Australia’s approach to the regulation of surrogacy is fragmented. The separate regimes in the states and territories create a chequerboard of regulation in which the families involved in surrogacy are reduced to little more than pawns in the game of procreative chess. Aside from an almost6 uniform prohibition of commercial surrogacy, there is little, if any, consistency between the states and territories. These differing approaches provide only a warped reflection of each other; a reflection that does not fit with reality. Eligibility to engage in surrogacy varies significantly between jurisdictions and there are even provisions which make it illegal for Australian residents to enter into surrogacy agreements interstate or overseas.7 The following brief account of the current legislative regimes provides insight into the disparity of approaches. A. Smoke and Mirrors: Key Aspects of Australia’s Surrogacy Legislation The following key issues in surrogacy regulation have been selected for detailed consideration in each jurisdiction:8 • enforceability of surrogacy agreements; • eligibility of parties to enter into surrogacy agreements; • territorial restraint; • offences; and • parentage. For convenience, two tables appear at the end of this chapter. Table 4.1 provides a synopsis of the current surrogacy legislation across Australia, while Table 4.2 contains a summary of the current parentage legislation in Australia. This discussion of Australian surrogacy legislation serves to highlight the inconsistencies between jurisdictions and to create the backdrop for the proposed national model. Millbank notes that in the ‘new era of openness to surrogacy, the twin themes of ‘altruism’ and ‘national harmony’ dominated’.9 On the theme of national harmony it has been established that inconsistent regulation fails to provide the ‘greatest net benefit to the community’,10 which in turn undermines society’s capacity to achieve desirable social and economic goals.11 In order to achieve the greatest net benefit to the community, legislation should be clear, concise and consistent. The national model outlined in this chapter strives to achieve these objectives while not being unduly prescriptive on those it seeks to regulate.12 Unlike in some countries such as South Africa,13 Georgia14 and the Ukraine,15 where surrogacy agreements are legally enforceable, the Australian legislation deems all agreements to be unenforceable, save for payment of the surrogate’s reasonable16 or actual17 expenses. New South Wales, Queensland and Tasmania each place conditions on these payments. While New South Wales permits parties to enter into either pre-conception or post-conception surrogacy agreements,18 the legislation only allows claims for payment or reimbursement of the surrogate’s expenses where the agreement was entered into prior to conception.19 In Queensland the agreement must also be entered into prior to conception,20 but recovery of the surrogate’s reasonable expenses is also contingent upon the surrogate relinquishing the child to the intended parents21 and consenting to transfer of parentage.22 Similarly, Tasmania permits only pre-conception agreements23 and the surrogate’s right to reimbursement of expenses is contingent upon the consent of her and her partner (if any) to the transfer of parentage.24 In the 2012 case of LWV & another v LMH,25 the Queensland Children’s Court had an opportunity to examine the issue of conception in the context of a surrogacy agreement. As the Queensland legislation only permits pre-conception surrogacy agreements, but does not provide a definition of ‘conception’, the court was required to define conception and establish when it had occurred. On the facts of LWV, an embryo was created in 2008, a surrogacy agreement entered into in April 2011, and the embryo implanted into the surrogate in July 2011. The resulting child was born on 22 March 2012. In considering whether it was appropriate to grant parentage orders, Judge Clare SC had to be satisfied that all26 the requirements of section 22 of the Surrogacy Act 2010 (Qld) had been complied with. The only apparent impediment to the granting of the orders was whether the surrogacy agreement had been entered into prior to the conception27 of the child (given that the embryo from which the child resulted was created in 2008). Her Honour found that the answer seemed ‘straightforward’28 regardless of the method of statutory interpretation employed, and that conception occurred at ‘the commencement of the pregnancy, which involves an active process within a woman’s body’.29 Her Honour reasoned that the commonly used phrase ‘conceived a child’30 refers to an actual (as opposed to a possible) pregnancy. Expert evidence was led that the 2008 creation of the embryo was ‘an act of fertilisation’31 which is ‘a step on the path way to conception’.32 Ultimately, Judge Clare SC determined that the surrogacy agreement had been entered into before conception, thereby satisfying the legislative requirements. Parentage orders were granted to the intended parents and the case cemented its place in surrogacy (and potentially even ART)33 history by providing a world-first34 ruling that conception occurs with pregnancy, not fertilisation. In the absence of any other judicial discussion on this topic, this decision is the first step in putting to rest any uncertainty that may have previously existed about when conception occurs in a surrogacy or ART context and can be relied upon to satisfy the legislative provisions that require surrogacy agreements to be entered into prior to conception. Further, by demonstrating that the parties have complied with all legislative requirements regarding formation and performance of the agreement, the surrogate’s entitlement to reimbursement of her expenses is preserved. To be eligible for surrogacy, intended parents must usually satisfy the requirement that the surrogacy agreement arises in response to either a medical or a social need. The specifics of eligibility in each jurisdiction are discussed below, but the requirements are largely designed to prevent fertile intended parents from accessing surrogacy purely for reasons of convenience. For medical eligibility, the threshold requires the intended mother to be unable or unlikely to conceive, carry a pregnancy or give birth or to have some other significant medical or genetic risk associated with pregnancy. A social need occurs in the context of singles and same-sex couples35 where natural procreation is physically impossible, even in the absence of any medical infertility. Victoria requires surrogacy agreements necessitating ART to be assessed by, and receive approval from, the Patient Review Panel.36 The Panel’s assessment criteria is aimed at protecting the welfare of children born through surrogacy,37 as well as that of the surrogate, by ensuring that the surrogate has attained ‘a sufficient level of maturity to be able to understand the implications of entering into the arrangement’38 including the legal and personal consequences of the arrangement not proceeding as anticipated. Similarly in Western Australia, in order to ‘minimise the risk of harm to the parties involved’,39 pre-conception40 surrogacy agreements require the consent of the Reproductive Technology Council,41 which necessitates an independent review of the proposed agreement. From a practical perspective, requiring an independent body to approve the surrogacy agreement creates a record which is then available to a child who may wish to gain information about their conception and birth at a later date.42 Access to records is important because Western Australia, in particular, permits the use of donor material in surrogacy arrangements. In cases where donor material is used, the donor is deemed to be a party to the arrangement and is required to sign the surrogacy agreement.43 The importance of keeping proper records of donated genetic material has recently been highlighted in Denmark where a sperm donor carrying the rare genetic condition Neurofibromatosis type 1 (Von Recklinghausen’s disease)44 is believed to have fathered 43 children in 10 countries, passing that condition onto at least five of those children.45 Efforts must now be made to contact the parents of those children to inform them of the possibility of transmission of the disease. For eligibility based on marital status or sexual orientation, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and the ACT all permit singles and same-sex couples to undertake surrogacy. At the time of writing, Queensland also permits singles and same-sex couples to enter into surrogacy agreements. However, following a change in state government, a potential amendment of the eligibility criteria was flagged by the government, with the possibility that singles and same-sex couples may in the future be ineligible for surrogacy.46 Western Australia limits eligibility to single women and heterosexual couples who satisfy the definition of an ‘eligible person’47 or ‘eligible couple’.48 These definitions have the effect of excluding single men and gay couples from accessing surrogacy in that state. For lesbian couples, it is foreseeable that one of the partners may be able to satisfy the definition of ‘eligible person’ and could thereby make the application as an individual. While this is obviously not an ideal situation, it is the only mode by which a lesbian couple can circumvent the Act’s eligibility provisions. Even more restrictively, South Australia renders all singles and same-sex couples ineligible for surrogacy. The provisions of the South Australian legislation permit only legally married49 or heterosexual de facto couples50 to undertake surrogacy. These provisions were enacted notwithstanding the 2007 report of the South Australian Parliament Social Development Committee which ‘heard no evidence to suggest that either marital status or sexual preference can predict whether or not an individual will be a good parent’.51 Additionally, in referring to the decisions in Pearce v South Australian Health Commission52 and McBain v State of Victoria53 which both found that prohibiting single women from accessing ART was inconsistent with the Commonwealth Sex Discrimination Act 1984, the Committee expressly declared that it ‘does not support the restriction on surrogacy based on discriminatory criteria’.54 The eligibility provisions of the South Australian and Western Australian legislation may eventually be subject to a Pearce- or McBain-type challenge and if (or when) that happens, it is likely to lead to a decision in favour of non-discriminatory access to ART for the purpose of surrogacy. Anita Stuhmcke’s Chapter 5 in this volume provides a comprehensive coverage of this topic, and therefore this section is brief. There are three Australian jurisdictions that impose territorial restraint on surrogacy: Queensland, New South Wales and the ACT. The Queensland legislation extends its application beyond state borders by declaring it to be an offence for a resident of Queensland to advertise for surrogacy, enter into a commercial surrogacy agreement or provide technical, professional or medical services for a commercial surrogacy agreement, regardless of whether or not the act was done in Queensland.55 The New South Wales surrogacy legislation extends the scope of its offence provisions by establishing a link56 with the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW),57 creating a geographical nexus when an offence is committed outside New South Wales but has effect within that state. Therefore commercial surrogacy undertaken outside New South Wales but which has an effect in that state is prohibited. This provision is particularly relevant in terms of the recent trend towards what has been labelled ‘reproductive tourism’ or ‘fertility tourism’ in jurisdictions where commercial surrogacy is permitted, such as (until recently) India, Mexico and the United States. Any person participating in a commercial surrogacy agreement outside Australia with the intention of bringing the child to New South Wales commits an offence. In Johnson and Anor & Chompunut58 Watts J discussed this newly created geographical nexus, noting that those people ‘resident and/or domiciled in New South Wales do commit an offence if they enter into a commercial surrogacy agreement whether within New South Wales or anywhere outside New South Wales’.59 Notwithstanding the court’s acknowledgement of this offence, to date there have been no reported prosecutions under these provisions. The other jurisdiction to impose a territorial restriction on surrogacy is the ACT. The Parentage Act 2004 (ACT) expressly acknowledges the operation of section 64(2) of the Criminal Code 2002 (ACT) which creates a geographical nexus for offences committed within the ACT, whether or not they have any effect in the ACT, and offences committed outside the ACT but that have an effect in the ACT. This operates in the same manner, and has the same effect, as its counter-part in New South Wales. These territorial restraint provisions, Millbank posits, ‘will not prevent Australians from engaging in paid surrogacy overseas, nor do anything to render that practice less risky for any of those involved’.60 Criminalisation, she argues, ‘may inhibit constructive discussion about how domestic surrogacy could be expanded or international surrogacy made safer’.61 Stuhmcke’s Chapter 5 in this volume discusses these criminal offence provisions and she argues that, in the absence of demonstrable harm, the government should not apply moralistic legislation which has the effect of restraining a person’s procreative liberty. While offences under the various Acts are similar, all containing restrictions on advertising and an express prohibition of commercial surrogacy, Queensland, Western Australia and the ACT also prohibit the provision of any technical or professional services for commercial surrogacy.62 In terms of advertising restrictions, Queensland prohibits advertising a willingness to enter into a surrogacy agreement63 or advertising in a manner that is designed to induce entry into a surrogacy agreement.64 The South Australian legislation contains similar provisions while in the ACT it is an offence to enter into, procure65 or advertise with the intention of inducing someone to enter into a commercial surrogacy agreement.66 New South Wales prohibits advertising or soliciting for participants in commercial surrogacy agreements.67 In Western Australia it is also an offence to receive payment for introducing parties to a surrogacy agreement (whether or not the arrangement itself is commercial)68 and to advertise a willingness to make a commercial surrogacy agreement.69 Tasmania prohibits the commercial brokerage or advertising of surrogacy agreements70 and also declares that it is an offence to publish particulars of any application for parentage or other orders where publication may lead to the identity of the parties being revealed.71 Finally, Victoria’s offence provisions state that it is an offence to advertise a willingness to be a surrogate, enter into or procure a person to enter into a surrogacy agreement, seek a participant in or be willing to arrange a surrogacy agreement or accept a benefit under a surrogacy agreement.72 These offence provisions appear to have been incorporated into the surrogacy legislation as a matter of public policy to minimise the potential for harm to occur in surrogacy transactions and to safeguard against the commercialisation of the practice. Commercialisation in this regard refers not to commercial surrogacy (where the surrogate receives payment for her services) but rather to profit-making surrogacy agencies as often seen in the United States. By prohibiting third parties advertising for, inducing or introducing parties to a surrogacy agreement, the legislative provisions represent a proactive approach to protecting parties to a surrogacy agreement from the risks of commodification and exploitation. All Australian jurisdictions presume the birth mother to be the legal mother of a child born through surrogacy, but there are different presumptions relating to legal fatherhood (or parenthood in the case of a same-sex partner).73 Similarly, there are variations on the mechanisms for transferring legal parentage of any child born through surrogacy. Before any court grants an order transferring legal parentage, irrespective of jurisdiction, it must be satisfied that doing so is in the best interests of the child.74 This principle, enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child,75 is reflected in domestic legislation76 which requires that in all decisions regarding children, their parenting or welfare, the child’s best interests are paramount.77 Similarly, in all applications for transfer of legal parentage, unless there are legitimate reasons for not doing so (such as death, disappearance or loss of capacity), the surrogate and her partner (if any) must consent to the orders being sought by the intended parents. The various legislation provides differing mechanisms and timing for the transfer of legal parentage; vesting power in their Magistrates’,78 Children’s,79 Supreme,80 County,81 Youth82 or Family83 Courts to decide these matters. While all Acts require applications to be made no later than six months after the child’s birth, the earliest time for the lodgement of an application for the transfer of legal parentage varies between 28 days,84 30 days85 and six weeks86 after the child’s birth. Further, the South Australian87 and Western Australian88 Acts preclude same-sex couples from seeking parentage orders. B. Where to from Here? ‘Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?’ ‘That depends a good deal on where you want to get to’, said the Cat.89 (Alice and the Cheshire Cat, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland) It is evident from the above examination of Australia’s surrogacy legislation that, while there are elements of consistency, there is also significant disparity between the various jurisdictions. If Australia is to effectively regulate surrogacy, consensus must be reached between the states and territories as to an appropriate legislative framework. Although, in Australia, most steps towards harmonisation of laws have occurred in the sphere of commercial law,90 there are signs that this is changing with moves underway to harmonise occupational health and safety laws.91 Surrogacy is an issue that is in urgent need of a nationally uniform approach, whether through consistent state and territory enacted legislation or by referral of power to the Commonwealth. Indeed, this view is reflected in the 2009 Standing Committee of Attorneys-Generals’ A Proposal for a National Model to Harmonise Regulation of Surrogacy (the SCAG Proposal)92 considered below. To venture an opinion is like moving a piece at chess: it may be taken, but it forms the beginning of a game that is won.93 For some time commentators have called for national reform of surrogacy legislation. In particular, Willmott believes that ‘failure to support this form of assisted reproduction by putting in place an appropriate legislative and regulatory framework to the same extent as exists for other forms of ART cannot be justified’.94 She emphasises that ‘surrogacy agreements are not isolated occurrences’95 and as a result, ‘there is a need for uniform legislation’.96 Notwithstanding this need, as recently as 2011, the difficulties of undertaking national surrogacy reform were highlighted. In Lowe & Barry and Anor,97 which dealt with an application for orders for parental responsibility following a traditional altruistic surrogacy agreement between family members, Benjamin J observed that: The law in Australia in relation to surrogacy is complex. There is no uniform legislation between the States and Territories governing surrogacy. The Commonwealth Government lacks the constitutional power to enact effective national legislation.98 Referring in that judgment to another surrogacy case, Dudley and Anor & Chedi,99 His Honour continued: However, there is some indication of policy development. Watts J observed: In very recent times Australia has been moving towards a uniform position in relation to the legality of surrogacy agreements and all places in Australia, except Tasmania and the Northern Territory, now have laws about surrogacy agreements.100 In the absence of constitutional power to enact uniform surrogacy legislation, it will be incumbent upon each of the states and territories to either refer legislative power to the Commonwealth under 51 (xxxvii) of the Constitution, or agree to each enact consistent legislation. The division between the law-making powers of the Commonwealth and the states and territories is founded on the general principle that ‘private rights were regarded as more appropriately a matter for the states than for the Commonwealth’.101 Therefore, from a practical perspective, referral of power to the Commonwealth is unlikely. Even though there have been instances of referral of powers in relation to matters concerning the welfare of children (for example, to encompass coverage of ex-nuptial children),102 states and territories are generally loath to surrender their law-making autonomy. Therefore, if national reform is to occur, attention should focus on encouraging the states and territories to reach consensus as to an acceptable national surrogacy model that considers not only the mechanics of the surrogacy agreement itself, but also broader policy considerations including respect for autonomy, harm minimisation and the privacy of the parties. Scholars, including Stuhmcke103 and Willmott,104 have discussed the possibility of a national regime, with Stuhmcke noting in 2004, that ‘in Australia, incremental legal change is now occurring to allow surrogacy without national debate’.105 At the national level, the Standing Committee of Attorneys-General (SCAG) undertook an investigation into altruistic surrogacy, and in 2009, the Joint Working Group submitted the SCAG Proposal which discussed a national model for the regulation of altruistic surrogacy across Australia. While steps have yet to be taken to implement the SCAG Proposal, it provides further hope that national reform can soon begin. Founded on elements of the Victorian, ACT and Western Australian surrogacy legislation, the aim of the SCAG Proposal was to ensure that intended parents are formally ‘recognised throughout Australia as the legal parents of the child in place of the birth parent(s)’.106 Accompanying this aim, the following principles underpin the SCAG Proposal: • Parentage orders should only be made if they are in the best interests of the child. • Legal disputes between the intending parents and the birth parent(s) should be avoided.107 The national model proposed in this chapter supports these principles and acknowledges the liberal beliefs entrenched in Australian society that ‘governments should not prohibit private activity unless that activity does harm to others’.108 As such, in the absence of significant demonstrable harm, people should be at liberty to make decisions regarding the conduct of their lives, including decisions regarding their procreative choices. Writing in support of the liberty of private citizens, John Stuart Mill stated that ‘the only part of the conduct of anyone, for which he is amenable to society, is that which concerns others … over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign’.109 The national model would widen the scope of existing legislation so that both altruistic and commercial surrogacy are regulated. In relation to commercial surrogacy, academic debate exists on the issue of whether or not its prohibition in Australia is justified. Since as early as 1996,110 Stuhmcke has called for law reform in this area, asserting that the ‘continued application of criminal penalties to commercial surrogacy requires review’.111 The proposed national model would regulate commercial surrogacy rather than criminalising it. This proposal may be controversial, but it is not radical. It is consistent with academic thought over time, and justified because governments should not intervene unnecessarily in the lives of private citizens, except when there is concern that one citizen’s actions can result in significant harm to another.112 Scott concludes that a ‘contemporary pragmatic approach to regulating surrogacy’113 should be adopted over absolute prohibition. She advocates that ‘well-designed regulation can greatly mitigate most of the potential tangible harms of surrogacy, and this would seem to be the appropriate function of law in a liberal society in response to an issue on which no societal consensus exists’.114 For the child, these tangible harms can include ‘attachment disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, psychosomatic symptoms and mental health problems’.115 However studies on the cognitive and social development of children born through ART conducted from infancy to adolescence, reveal ‘comparative cognitive functioning to other children and in some cases … higher in social and communication skills’.116 But, irrespective of how alternative families117 are formed, Beckett et al. identify that ‘one additional role unique to substitute parenting is the need to explain to the child their origins and to help them to make sense of their beginnings’,118 and parents need to appreciate that ‘open communication appears to be … positively associated with self-esteem’.119 Through appropriate regulation of commercial surrogacy such safeguards (including requiring pre-approval of surrogacy agreements, ensuring the availability of information regarding the child’s conception and providing access to counselling for the resulting child) can be introduced to minimise the risk of harm occurring. Turning to the surrogate, Appleton suggests that ‘while surrogacy opens a window of opportunity to many childless couples it is also open to abuse’.120 It is therefore imperative to protect surrogates from exploitation which occurs when a person’s wrongful behaviour violates ‘the moral norm of protecting the vulnerable’.121 Interestingly though, van den Akker’s research reveals that notwithstanding a tendency for surrogates to have a lower level of education and come from a lower socio-economic class than the intended parents, rather than feeling exploited, surrogates believe that they made an informed choice when they decided to bear a child for another.122 There is undoubtedly scope for commercial surrogacy to be harmful; but the same could also be said for altruistic surrogacy which is now considered to be an acceptable practice in Australia.123

Through the Looking-Glass: A Proposal for National Reform of Australia’s Surrogacy Legislation

I. Introduction

II. A Chequerboard of Regulation: Australia’s Surrogacy Legislation

1. Enforceability of surrogacy agreements

2. Eligibility to enter into surrogacy agreements

3. Territorial restraint

4. Offence provisions

5. Parentage

III. Through the Looking-Glass: National Reform

A. The Proposed Model

1. Scope