Through the lens of morality: just war and public diplomacy

4 Through the lens of morality

Just war and public diplomacy

[W]herein two things are to be proved, the one that a just feare (without an actuall invasion or offence) is a sufficient ground of Warre, and in the nature of a true defensive; the other that we have towards Spaine cause of just feare, […] not out of umbrages, light jealousness, apprehensions a farre off, but out of a clear foresight of imminent danger.

Sir Francis Bacon, 1624

War in defence of life is permissible only when the danger is immediate and certain, not when it is merely assumed. I admit, to be sure, that if the assailant seizes weapons in such a way that his intent to kill is manifest the crime can be forestalled; […] But those who accept fear of any sort as justifying anticipatory slaying are themselves greatly deceived, and deceive others.

Hugo Grotius, 1625

Moral debate over war has been with us for centuries, and its historical filiations in the Western world are best traced through the familiar just war doctrine. Its protracted existence and constantly developing recurrence in Western thought speaks to the depth to which the moral dimensions of war run within the populations from which it sprang. Even though there has been a history of formulating a reasoning for casting aside any ethical and legal considerations in war-making, classical, modern, and contemporary forms of moral (at times mixing clearly with legal) analysis are a testament to the durability and relevance of such an approach. However, it should be remembered that limits on warfare have come together over scores of years from an amalgamation of sources. These include Christian theologians who developed a moral doctrine inside the church, international lawyers who enunciated principles that guided and set in motion the first texts of this discipline, and military professionals who focused on considerations of fair play rooted in chivalry (Turner Johnson 1981). Therefore, as the just war theory will serve as the overarching vehicle that will drive this axiological analysis, it should be understood as a relatively imprecise term that rightfully reflects the intersection of the vital concepts of law, morals, and prudence. As such, it is certainly a fitting tradition to be used in this work treating the equally interdisciplinary subject of legitimacy.

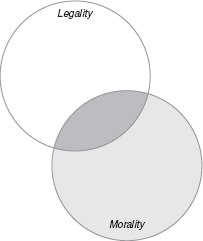

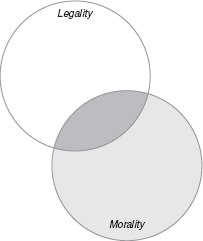

In Chapter 1, we discussed the concept of overlap and shone a light on a coincidence that exists between legality and morality. In particular, we spoke to the prohibition of free violence that must exist in any and all legal or moral codes. This exclusion directly relates to the work of this chapter as we will be exploring the rules that have been laid down over the centuries for reducing or eliminating unconstrained military attacks. As this will not be an exhaustive study of just war theory, we will focus on the primary aspects of the tradition that are directly pertinent to the justifications put forward for the invasion of Iraq in 2003. The classic doctrine of just war had three basic requirements—right authority, just cause, and right intention—and these conditions provided the fundamental shape for how the theory would further develop over time. Nevertheless, these basic criteria also held within them concepts that have become more explicit, including that war must only be defensive in nature, that it is to be used only as a last resort, that there be a reasonable chance of success, and that armed hostilities are proportional to the harm that was suffered. In this chapter, we will explore the three particular concepts of “anticipatory attacks” for self-defense, “last resort,” and “right authority” since they are most directly relevant to our question here.

While all of these criteria from the just war theory correlate to the attempt to exclude wanton bloodshed from international society, our attention in the first half of this chapter will be focused on the distinction between “preemptive” and “preventive” war. The divergence found between these two terms and concepts helps explain the disquiet that grew over what has become known as the “Bush Doctrine.” As will be seen, there was an important bifurcation in the just war tradition during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, and a part of the cleavage was based on this very issue of anticipatory attack (a point masterfully illuminated by Turner Johnson 1975 cf. O’Driscoll 2008: 27–50). While some advocated that a “just feare” was a reasonable standard for triggering war (an argument that resulted in no progeny), others insisted that the criteria for launching an attack must be more objective and verifiable (argumentation that helped found international law).

Although it is often forgotten, there was a call within the US (if only by poll) for a sanctioned justification by the UNSC before the invasion of Iraq (Kull et al. 2003/2004: 569, note 1), lending validity to the idea that in a notable number of people’s minds this body indeed holds the mandate found within its charter. What this meant was that the debate over an invasion of Iraq manifested itself in two primary ways that directly affected public diplomacy: first, there was a worldwide movement of people who descended into their streets to protest this anticipatory attack, making it clear that there was a “moment for deliberation”; second, this display of objection coincided with one of the most high-profile diplomatic debates of contemporary times at the UNSC over the question of whether an invasion on the grounds presented would be legal and moral. All of this demonstrated a growing belief that Article 39 of the UN Charter indeed vests the UNSC with the “right authority” to “determine the existence of any threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression.” Thus, the second half of this chapter will treat the significance and the details of this diplomacy taking place on a public stage.

To once again clarify the overlap that exists between legality and morality, we return to The Concept of Law, where H. L. A. Hart put forward a list of five essential causal connections between natural conditions and systems of rules. There are two which primarily concern us in the discussion of a restriction on unprovoked violence: human vulnerability and approximate equality (Hart 1994: 194–195). The first of these connections deals with the exposure that every human confronts when interacting with others. Each of us is vulnerable to bodily attack that could shorten or end our existence, and, as such, we enter into a societal contract (either implicitly or explicitly) which requires mutual forbearance by all members. Hart described the basic starting point for all rule-governing interaction by stating that “[o]f these the most important for social life are those [prohibitions] that restrict the use of violence in killing or inflicting bodily harm” (1994: 194). So vital is this protection to our human vulnerability that without it there would be no reason to have rules of any other kind.

The second causal connection dealing with equity in treatment springs from only slight differences in strength, dexterity, speed, and intellectual capacity that exist between all persons. Yet, no one is so superior that they possess the capacity to single-handedly subdue or dominate others for more than a short time. Even the strongest or shrewdest among us must drop their guard for repose and sleep at some point. As such, this natural condition of negligible inequality, because it is only transitory by nature, leads to the need for a system of rules that balances out these slight inherent differences and places all persons on a level playing field. As Hart explains,

[t]his fact of approximate equality, more than any other, makes obvious the necessity for a system of mutual forbearances and compromise which is the base of both legal and moral obligation. Social life with its rules requiring such forbearances is irksome at times; but it is at any rate less nasty, less brutish, and less short than unrestrained aggression for beings thus approximately equal.

(Hart 1994: 195)

Thus we will proceed on the assumption that there is indeed a very important overlap between morality and law at the precise point which concerns us in this chapter. Survival, or self-preservation, is a shared value among all humans, and this mutual interest stretches across borders, cultures, or tribes.

Hart himself argued in 1961 that the inequality of states renders the requirement of a prohibition against free violence as unsuitable to the international realm. However, there is good reason to doubt that this reasoning remains applicable. For example, the fact that governments now regularly invoke self-defense in protecting themselves against non-state actors suggests that this disparity is irrelevant because even individuals can cause significant harm with today’s weaponry. Additionally, the fear that weapons of mass destruction could end up in the hands of violent persons again changes this calculus of great inequality in the international sphere. It is thus argued that the difference in strength is no longer wholly relevant.

There are certainly some who argue that such analogies are inappropriately applied because international relations should be understood as realpolitik, and every state preserves its own raison d’état, thus invalidating moral and legal perspectives. In other words, politics between nations must be understood through a nation’s material considerations and national interest rather than through abstract ideals. However, in the circumstance before us, we are analyzing the legitimacy of a regime or policy, and, therefore, the perception of individuals, and public opinion at large, are directly consequential. Even though there was indeed an historical moment in which states unblushingly argued that recourse to war was their own prerogative to exercise at will and that any appeals to international laws were meaningless, this was an idea that “never seized the public imagination” (Walzer 1977: 63). Thus, since legitimacy most certainly turns on the perceptions of people and their individual will to obey the government, the domestic analogy loaded with concepts of right and wrong, good and bad, along with morality and immorality, is directly pertinent here for our analysis of the use of force in the “war on terror.” It would seem absurd to assume that a public is readily and easily going to extract itself from calculations of war, particularly when all are asked to support it, and members of the society are asked to kill and be killed. As Michael Walzer points out, “[u]ntil wars are really fought with pawns, inanimate objects and not human beings, warfare cannot be isolated from moral life” (1977: 64).

Of course, this jus ad bellum discussion of the invasion of Iraq that is to follow raises at least two other questions: how does the question of legality relate to Operation Enduring Freedom which committed a coalition of armed forces into Afghanistan? And what jus in bello questions are relevant for evaluating morality and the “war on terror”?

Due in large part to the unanimously approved UNSC Resolutions 1368 and 1373, offering an authoritative interpretation of the character and legal meaning of the 9/11 attacks, the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 in reaction to the attacks on US soil rested on very different legal grounds than that of the mobilization of troops into Iraq. The specific use of language in both resolutions—“the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence”—has largely been taken by international lawyers to mean that the UNSC determined that 9/11 had indeed triggered a right to respond with force. Additionally, in letters submitted to the UNSC, both the US and the UK justified the military operation in Afghanistan as individual and collective self-defense (Permanent Rep of US to UN 2001; Permanent Mission of UK 2001).

As to the second question raised, specific examinations of jus in bello regarding the “war on terror” will be primarily limited to the issues of detention without judicial review and torture and ill-treatment during interrogations that are to be found in the previous and following chapters. There is no doubt that the means by which a war is waged factors directly into the calculations of its moral character, which can be plainly surmised through its later inclusion into the doctrine of just war. For this reason, two complete chapters of this work are dedicated to analyzing particular aspects of humanitarian and human rights law in war, although through somewhat different lenses of analysis. To be sure, the war in Iraq raised other jus in bello questions, such as the use of white phosphorous against insurgents and civilians during the assaults on Falluja, the use of cluster bombs, and whether feasible precautionary methods in targeting were properly implemented. However, the scope of this work will not include the armed-conflict operations in Iraq after invasion and will instead concentrate on the jus ad bellum question of law and morality.

This chapter is organized around an application of the most pertinent portions of the tradition that has served as the baseline of moral analysis in Western civilization for at least some 1,500 years when it comes to armed conflict. We will begin by tracing the historical filiations of the just war tradition on the question of anticipatory military action in Section II. It will be demonstrated that the distinction between preemptive and preventive war is one that has long existed and forms a critical understanding within the tradition that armed hostilities must be launched in response to a verifiable injury. In Section III we will deal with what has become known as the “Bush Doctrine.” This was presented to the public as a “preemptive” policy, although it is more properly termed “preventive war.” Yet, in the end this rhetorical sleight of hand could not hide the war in Iraq’s moral failings as the claims of future dangers showed themselves to be nothing more than erroneous suspicions.

In the second half of this chapter, beginning in Section IV, there will be a treatment of whether military confrontation was employed as the “last resort.” It will entail a discussion of the manner in which morality inevitably enters into such debate when there is clear evidence of a choice through a public “moment for deliberation.” In Section V there will be a discussion of “right authority” in the context of the United Nations as the world’s public forum for diplomacy. Here it will be argued that the “right authority” of the UNSC was bypassed through expedient interpretations which transferred a questionable authority into the hands of governments to unilaterally sanction the opening of hostilities themselves.

Finally, Section VI will provide conclusions while pointing out that the Obama administration has also honed in on the precise question of “imminence” as the standard for anticipatory lethal force across international borders in its unmanned drone program rendering the historical research of this chapter acutely pertinent once again.

II Anticipatory attacks and the just war doctrine

In this section, we will provide an historical analysis of one specific aspect of the just war doctrine to analyze an important part of the argument put forward by the Bush administration for a war against Iraq—often popularly termed the “Bush Doctrine.” Although this did not become the official reasoning for the invasion, this doctrine did enter directly into the popular debate over war policy. The intention here is to trace some of the history of discussion over the difference between preemptive and preventive war to show that there is indeed a significant chasm that exists between these two standards of anticipatory self-defense. This gulf will be shown to be one that has long existed within the just war tradition, and thus it can be understood as an identifiable stark moral and legal line. One primary reason for a self-imposed prohibition of this nature would simply be for exercising the use of force only in a manner that is likely to be deemed legitimate by citizens. When this line is crossed, one leaves the solid ground of what is knowable or known, for the shaky and unverifiable position of war based upon conjecture of our enemy’s future intentions.

Of course, as discussed in Chapter 2, self-defense as a legal doctrine did not emerge until after there was an explicit codified prohibition of the use of force; the two concepts clearly go hand in hand since you must have a prohibition before there is an exception. As we will see in our investigation of the just war doctrine, there has long been discussion over the justness of different types of defensive anticipatory action. It was only during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that it was argued that every state had an uninhibited right to wage war completely at its own discretion. During that period states could generally “resort to war for a good reason, a bad reason or no reason at all” (Briggs 1952: 976, cited in Dinstein 2001: 71). Regardless of this historical gap, it is useful to first plot out the different forms of defense that have been contemplated and to place them on a timeline. In this way, we will provide a coherent shape to our discussion of the moral and legal delineations of anticipatory war in the just war doctrine and contemporary international law.

The most useful breakdown of the different modes of anticipatory action is in terms of four temporal moments: reactive self-defense, interceptive self-defense, preemptive attack, and preventive war. (While some terms have been adjusted slightly, the outline comes from Kolb 2004: 122–125).

Reactive Self-Defense: This action is the one most obviously contemplated within the text of Article 51 of the UN Charter. The language of the provision clearly allows for the use of force “if an armed attack occurs,” but there is also the explicit requirement that the state exercising self-defense bring the situation immediately before the UNSC so that it can take steps to restore peace and security. This is surely the most uncontroversial type of action, even if some doubt remains about what intensity of assault rises to the level of an “armed attack.”

Interceptive Self-Defense: This action can be described as that undertaken by a state to interrupt an attack that has already been launched but that has not yet struck its target. Examples would include the disruption of a launched missile, aircraft or sailing naval fleet. Some have likened this action to a hypothetical attack by the US on the Japanese naval fleet before it reached Pearl Harbor. Of course, the validity of such an action depends upon the accuracy of intelligence information analyzing threats and coming assaults. However, few would question the justifiability of intercepting an onslaught already underway.

Preemptive Attack: This act raises the eyebrows of some jurists who believe that it crosses the line of legality because verifiability in retrospect is extremely difficult, if not impossible. This is in addition to the fact that, once again, one becomes wholly reliant upon excellent or perfect security intelligence. However, the critical element that solidifies this particular action in our time axis is that of immediacy. In international law, the term that the majority of jurists focus on as paramount for defining this type of deed is that it is triggered by a strike that is imminent in time. Troop movements to an international border, visible military preparations for an attack, or even a declaration that an act of violence will soon be under way are some of the observable circumstances that would demonstrate this imminence. The example that is often put forward for this form of self-defense is the case of Israel’s attack on Egypt in 1967 in response to a troop buildup in the Sinai Peninsula and escalating belligerent rhetoric between the states (Walzer 1977: 80–85; cf. Popp 2006).

Preventive War: This final variety of action is purported to be a defensive use of force against an adversary that is not now preparing for immediate military confrontation but the risks involved in waiting for a timing of the enemy’s choosing are too great to warrant restraint. This act is surely the most questionable when it comes to international law because of the palpable lack of immediacy. This is not to mention the fact that it is impossible to apply proportionality and necessity, which are also a part of the customary law relating to self-defense. Most significant from a moral perspective is that any effort launched on the basis of such an idea or doctrine, while regularly justified through a loud rhetoric of fear and security, is based solely upon speculation and conjecture. In the just war doctrine, this particular type of action can be most often found under the descriptions of offensive war and that of attacking the growing power of a neighbor.

The intention of this section of our work is to focus a spotlight on the moral and legal difference between a preemptive attack and that of a preventive war. This disparity was glossed over in the presentation of the Bush Doctrine by the administration. Throughout the development of the just war doctrine, this distinction has been essential, and its filiation can be traced. This is not to say that no one has ever attempted to argue that preventive war based on fear and speculation of the unpredictable future should be deemed justifiable; rather, the point is that when this case has been made it falls in a distinctly different category not founded on moral and legal arguments. Thus the space separating preemptive attack from preventive war is best described as a chasm, or even a precipice.

The fact that nearly all groups who resort to mass violence seem virtually incapable of doing so without formulating a logic for its need certainly points to the fact that such reasoning is inherently human. This is regardless of whether the employment of war is used as tool for self-defense, punishment, peacemaking, politics, or otherwise. However, the filiations of the first recognized formulations of the justifiability of war-making, known as the just war doctrine, are traced back to St. Augustine of Hippo. Rather than pretending to trace the entire thread of thought on this vast subject, this survey will focus on some of the better known figures who have weighed in on limits in war, particularly on the subject of the difference between offensive and defensive wars. In doing so, it will be seen that there has long been debate over where exactly a line should be drawn between legitimate defense and unjust war.

As a starting point, it should be recognized that Augustine of Hippo left an ambiguous legacy for his successors. Part of this, no doubt, is due to the fact that in attempting to formulate a doctrine on the justness of the participation in war by Christians, Augustine had few “shoulders of giants” to stand upon so as to construct his own intellectual edifice. That is to say, Augustine was largely trying to cobble together political and legal thought that was not initially suited to or meant for application to a kind of rules or guidelines in international affairs. For example, Roman law did not contain much useful discussion of the structure of how relations with other independent political bodies should take place, other than to distinguish the immortal civitas from the mortal citizen. Cicero’s defense of the just empire “seems to have turned principally on a denial of the parallel between an individual and the respublica” (Tuck 1999: 22). This distinction was found to be morally unsatisfactory not only because of how it led to an unleashing of those in power from restraint, but also, more importantly, for what it meant for Christians asked to participate in unconstrained war-making.

As a result, one essential characteristic of this moral doctrine at its nascent stage (particularly important because of how directly it relates to our own discussion) was that of creating a very tight connection between human law and the conduct of warfare. In contrast to Roman law, Augustine made a direct correlation between the individual analogy in law to the interaction of political bodies. It should be recognized that it is this same moral parallel that common citizens are likely to employ when judging the legitimacy of the use of force. This fusion of justifiable legal rules and equitable treatment among humans to the international sphere typifies the classic just war doctrine. This is surely why we see it develop into the beginnings of international law. One eminent scholar has pointed to the very existence of “canon law” as evidence of this connection and asserted that this “linkage between the theologians and the lawyers, in this area, persisted throughout the Middle Ages, and is the most distinctive feature of the theology of war throughout the period” (Tuck 1999: 57).

The underlying assumption of the just war doctrine today is that there are indeed times when it is morally acceptable to engage in war, along with the supposition that, once begun, there continue to be ethical constraints on those conducting it. However, the earliest theorists did not necessarily begin their work with such assumptions and instead reasoned through the different possibilities to arrive at these now assumed conclusions. It was the firm establishment, by the likes of Augustine and then Gratian, that there were indeed circumstances in which Christians could participate in war that paved the way for what is now known as the just war doctrine.

Of particular importance for our discussion here is the powerful moral principle of “double effect” devised by Thomas Aquinas. This idea is central to understanding whether there could ever be a moral justification for killing. Thomas shrewdly drew an important distinction between carrying out a violent action with the intent to kill and taking a life while using violence to defend one’s own person. Not only was there an important moral distinction between the two acts, but this conceptualization of “double effect” also provided, and should continue to provide, an extremely useful guideline for determining under what circumstances self-defense can be plausibly invoked. In other words, “[t]he use of force had to be directed against the attack, not the attacker” (Fletcher and Ohlin 2008: 27).

Therefore, we must also arrive at the important conclusion that there must be an attack (perhaps imminent); otherwise there is nothing to repel. Thomas eloquently explained this significant concept, and it is well worth reproducing his words here:

Nothing hinders one act from having two effects, only one of which is intended, while the other is beside the intention. Now moral acts take their species according to what is intended, and not according to what is beside the intention, since this is accidental. […] Accordingly the act of self-defense may have two effects, one is the saving of one’s life, the other is the slaying of the aggressor. Therefore this act, since one’s intention is to save one’s own life, is not unlawful, seeing that it is natural to everything to keep itself in “being,” as far as possible.

(Thomas Aquinas (1265–1274) Summa Theologiæ, II-II: Q. 64, Art. 7;internal citations omitted)

Thomas formulated a fundamental distinction in the thirteenth century that even today sheds light on our understanding of the use of force or violence directed onto another. Killing or harm must come only as a side effect of our own needed and proportional self-preservation.

On the question pertinent to our analysis on immediacy, one can indeed find that the first documented thinkers on jus ad bellum did discernibly sketch out a basic requirement concerning an anticipatory attack—that is, just war must be in response to a specific wrongful act that has taken place. While there were three primary requirements for a just war in the classic doctrine—right authority, just cause, and right intention—implied throughout is the stipulation that “just war be of a defensive or retributive nature only; offensive wars and wars of preemptive retribution are not permitted” (Turner Johnson 1975: 46). And it was this distinction that was critical throughout the tradition: offensive war vs. defensive war. Not only was it a difference that mattered from the inception of the doctrine, but it is one that can be followed up to contemporary times.

This is certainly not to say that the first use of force was entirely ruled out by these early theologians. Thomas, for example, certainly did not do so, either implicitly or explicitly. But there was the fundamental requirement that some fault must have been committed, and thus there was an injustice that needed to be corrected. In other words, the idea of dealing with a sinful act that has not yet occurred through war was implicitly excluded throughout the classical writings. As one scholar of the tradition put it,

[a]ctual wrong must have been done, moreover; it is not enough for evil intentions to have existed. Preemptive redress of wrongs or punishment of sin (which to the medieval mind was an instance of redress of wrongs) is ruled out.

(Turner Johnson 1975: 38; original emphasis)

Therefore, we find that within the just war doctrine, those who first contemplated the moral limits that should constrain even those who were charged with the defense of large populations must still base the launching of war on veritable actions, and not on assumed future intentions. Thus, the space between preemptive and preventive war was a gap that has been thought to be critical for centuries.

b Transition to the modern era: a telling bifurcation over “just feare”

Sixteenth-century Europe was awash in blood spilled in the religious wars of the Protestant Reformation that lasted until the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 over 130 years later. At the very same time, Europeans were confronting the moral and legal ramifications of the 1492 “discovery” of a New World inhabited by a people previously unknown to them in lands formerly untouched by the peoples of their continent. The carnage and bloodshed that this confrontation of peoples unleashed in a struggle for dominance and riches has been well documented. In the crucible of these violent clashes there was a proliferation of serious thought on the justness of war and conflict, some of it novel and progressive and some of it self-absorbed and expedient.

This no doubt spawned a pivotal development in the just war doctrine. It was during this time period in Europe that the classic doctrine of just war was secularized and became what is now recognized as the discernible roots of contemporary international law, with direct implications for when anticipatory war could be legally employed. Moreover, we will see that during this era of violent conflict some devout religious thinkers morphed the traditional just war doctrine into a justification of war on spiritual grounds, with contrary conclusions on anticipatory defense. As such, thought surrounding armed conflict during this time period has been presented and classified as a division between humanist and scholastic traditions and simultaneously described as a bifurcation of the just war doctrine. Regardless of which school of thought one adheres to, there is an illuminating division over what constitutes a justifiable trigger for the launching of war.

i The humanist tradition and holy war

Some political philosophers have suggested that the most useful way to understand how the original strands of thought progressed on issues of war and peace through the sixteenth century is with the designations of “humanist” and “scholastic” traditions (see, for example, Tuck 1999: 16–77). The distinction between the two might be best described as the rhetorical versus the philosophical. The humanist tradition largely reflected a perspective taken by rhetoricians defending their population’s interests before its own political bodies entrusted with the welfare of those very people. Thus it can be understood as representing a relatively narrow self-interest. The scholastics took a wider philosophical view beyond just one community to formulate a precept that could be acceptable to all populations and governments concerned with the justifications of war. The first drew extensively on the texts and rhetorical writings of the Romans, who were openly skeptical of philosophy; and the second tradition was constructed from earlier Christian literature, along with the writings of the Greek philosophers.

Scholars of the humanist tradition often looked to the Roman orator and jurist Cicero to help formulate their own stance on issues of war and peace. One primary reason for this was that the idea of warfare fought in the interests of one’s own res publica, as often eloquently argued by one of the most versatile minds of Ancient Rome, resonated strongly within the humanist tradition. Although Cicero did indeed argue for anticipatory action against internal enemies such as Marcus Antonius, he also thought that there was a dramatic moral difference between the peoples of Christian civilization and all others. Thus, Cicero maintained that all strikes executed in advance of any proper harm were justifiable if the republic was threatened in some way. This significant Roman orator for the humanist point of view “repeatedly implied that the violence of enemies did not actually have to be manifested in order to be legitimately opposed by violence” (Tuck 1999: 19).

that should our lives have fallen into any snare, into the violence and the weapons of robbers or foes, every method of winning a way to safety would be morally justifiable. When arms speak, the laws are silent; they bid none to await their word.

(1931: 17; my emphasis)

In the end, the defense of Milo was unsuccessful. Such a claim was found to be at the very periphery of decency, if not beyond it, in the domestic law. Overall, even in Roman law, one finds that “the only ‘fear’ which could be pleaded in extenuation of an individual’s act was an immediate and obvious one” (Tuck 1999: 21).

What is most noteworthy about these citations from one of the humanists’ favorite sources is the explicit evacuation of both laws and morals from any reasoning concerning an application of the use of force. This was particularly the contention for a circumstance that can be construed as self-defense only if the future were already written and a known entity. Offering final clarification that he indeed thought permissible defense reached beyond what is described in this chapter as a breach, by allowing for attack on those assumed or thought to be preparing a future ambush, Cicero explicitly argued that “the slaying of a conspirator may be a justifiable act” (1931: 19; my emphasis). In other words, the belief that there is the planning of future injury is enough to unleash deadly punishment.

Another variety of the humanist tradition in this era, or of those who applauded warfare in the interests of their own community, can be found in the works of some Protestant thinkers who advocated the launching of hostilities against those who were not of the same religious persuasion because brutal conflict was ever-present and constituted a implacable threat during that era. The time period of the Reformation was marked by bloodshed over a deep and severe division between Catholics and Protestants within the Christian church. As a result, there were some who picked up the banner of the just war doctrine and used its terminology and framework to advocate the cause of “holy war” against religious enemies (Turner Johnson 1975: 81–149).1

This sixteenth- and seventeenth-century trend of employing religious grounds to justify war-making has also been identified as one branch of a bifurcation of the just war doctrine, leading to holy war in this case and the beginnings of a secularized international law in the other. It is important to recognize that argument in favor of warfare grounded in justifications based on difference in religious ideology was relatively limited in duration and has no direct progeny of which to speak. In other words, the philosophy that professed that it was indeed moral to attack a perceived enemy before any injury had been suffered was a relatively short-lived and limited historical phenomenon.

The country in which the translating of the just war doctrine into an advocacy for holy war was most identifiable was England. However, this is not to say that this position did not exist in other parts of the continent. Rather, our attention is drawn to the English idea of holy war because it was brought into particularly sharp relief in the light of a palpable rivalry with the staunch Catholicism and maritime dominance of Spain during this time period. One specific characteristic of this doctrine of holy war found at the time was a shift in emphasis away from the traditional just war concept of a limitation on the Christian’s right to make war, and instead a focus on the permission to go to war.

One of the commonalities found in these figures who advocated for the use of religion as a casus belli and conceptualized a reformulation in the classic doctrine of just war was indeed specifically on the point of anticipatory war. That is to say, those who promoted the idea of holy war also found it justifiable to forestall the evil intentions of another by initiating war rather than waiting for a first strike. One of the earliest calls for just such hostilities against Catholic Spain came from Stephen Gosson in his 1598 sermon at Paul’s Cross Church in a parish where many high-ranking government officials worshipped. The Trumpet of Warre oration gained a popularity that led to its later publication. Because there was no ongoing armed conflict with Spain at that time, “this sermon must be understood as a call to preemptive [or preventive by our terms] defensive war” (Turner Johnson 1975: 102). What this means specifically is that Gosson endorsed and encouraged the protecting of his religious sect and country by launching war on the Spanish, whom he identified as propagating offensive religious wars on the Continent. Most importantly, his contention was that such a campaign would simply be an exercise in self-defense because Spain’s assumed malevolent future intentions were considered enough to be a trigger to action.

This sermon anticipated the position of a more well-known English dignitary in the early seventeenth century: Sir Francis Bacon. While not a religious zealot, one of Bacon’s writings in particular dealt directly with the subject at hand: Considerations Touching a Warre with Spaine (1629). In this piece we see that Bacon wrote judiciously, and his position at the court of Queen Elizabeth and then at that of King James gave him the experience necessary to prudently craft his argument. However, he was unmistakably favorable to holy war in this study document, which was prepared for the King while he was serving as a special royal adviser in 1624. We see here that holding the position that religious causes could indeed give rise to justifiable hostilities once again led to the result that armed struggle could be waged in anticipation of a wrong, and could be based solely on perceived malicious intentions.

To Bacon’s mind, the defense of his religion was grounds enough to initiate a battle against the nation that had professed itself generally to be the protectors of the Catholic world. Most importantly, he saw this as self-defense. The memorable expression upon which he based this reasoning, and the leading thrust of the article under discussion here, was that of a “just feare.” If it could be discerned that another country, which proclaimed a different faith, was prepared for battle (regardless of whether this preparation was intended for its own defense or aimed specifically at one’s own country), then the initiation of armed conflict was in fact a response based upon justifiable reasoning. As Bacon explained it for the specific circumstance facing England,

[t]o proceed therefore to the second ground of a warre with Spaine; we have set it downe to be a just feare of subversion of our civill estate: […] wherein two things are to be proved, the one that a just feare (without an actuall invasion or offence) is a sufficient ground of Warre, and in the nature of a true defensive; the other that we have towards Spaine cause of just feare, […] not out of umbrages, light jealousness, apprehensions a farre off, but out of clear foresight of imminent danger.

(Bacon 1629: 8)

We see in this citation that Bacon certainly believed there to a justifiable reason to fear Spain, and that this was enough to trigger a war to be initiated (defensively) by England.

It is also interesting to note the cunning rhetorical flourish employed at the citation’s closing. By invoking the language of an “imminent danger” there certainly would be an understandable and perhaps unsuspicious draw to the logic applied by Bacon. However, it should not go unstated that the word “foresight,” no matter how clear, directly contradicts the imminence of which he speaks; it is unreasonable for something to be just about to happen at any moment, yet at some unspecific point in the future. Hence, the phrase “clear foresight of imminent danger” should be understood as a contradiction in and of itself. In other words, knowledge of the future has never been shown to be within our human capabilities, and therefore this is better understood as a linguistic embellishment meant to obscure, rather than a reasonable argument.

To be sure, there were (and continue to be) very practical reasons for the exercise of military power to be seen as just, and Francis Bacon also spoke to this necessity. In other words, a war deemed just would have a direct effect on its efficacy. Bacon identified both funding and troop morale to be vital to a military exercise and at once based upon the perception of the justice of the war-making. As such, we must take Bacon’s arguments and reasoning seriously since he recognized that the perceived justness of war would be an important element in rallying the necessary support at home and abroad. As he put it,

[t]here must bee a care had that the motives of Warre bee just and honorable: for that begets an alacrity, as wel in the Souldiers that fight, as in the people that affoord pay: it draws on and procures aids, and brings manie other comodities besides.

(Bacon, cited in Piirmäe 2002: 500)