Through the lens of efficacy: torture on suspicion

5 Through the lens of efficacy

Torture on suspicion

Some locutions begin as bland bureaucratic euphemisms to conceal great crimes. As their meanings become clear, these collocations gain an aura of horror. In the past century, final solution and ethnic cleansing were phrases that sent a chill through our lexicon. In this young century, the word in the news—though not yet in most dictionaries—that causes much wincing during debate is the verbal noun waterboarding.

If the word torture, rooted in the Latin for “twist,” means anything (and it means “the deliberate infliction of excruciating physical or mental pain to punish or coerce”), then waterboarding is a means of torture.

(Safire 2008)

In this final chapter we shall gaze through the lens of efficacy to analyze torture as an intelligence-gathering tool, and this examination will reveal that the issue shares a manifest overlap with our other two lenses of legality and morality. As discussed, the prohibition of torture in international law has reached the special status of an absolute norm of jus cogens, putting it on par with the crimes of slavery and piracy. Put another way, the international law on torture has a clarity and comprehensiveness—no torture, by any authority, against any individual, in any circumstances, anywhere in the world—that places it in a very select category of illegality. For international courts interpreting the laws against torture, its stark status of illegality is not affected by notions of efficacy, and thus the approach of this chapter is legally unorthodox.

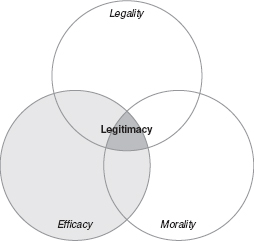

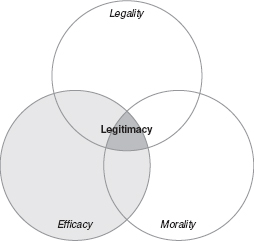

However, there is valid reasoning for this unconventional approach. Some national courts have entered into evaluations of efficacy that have traditionally been reserved for the political branches; there have been important decisions dealing with counterterrorism policies by national courts from Israel to Germany that utilized the aspect of efficacy to render their judgment. Yet what must remain front and center is that this work focuses on the legitimacy of the “monopoly of physical force” exercised by the government, and therefore valid policy must aim at defending this core of society that is being targeted. When we speak about state-sanctioned torture, we are looking at the exercising of the government’s most coercive and violent dominance over a defenseless individual. Because of the perceived immediacy and necessity that is coupled with the use of torture for intelligence-gathering, any systematized controls that might exist are often discarded as too cumbersome, and torture becomes an unchecked exercise of the government’s power. Employing profoundly forceful authority in a capricious manner cannot bode well for defending legitimacy.

To begin, it is necessary to define what is meant by efficacy in the specific context of a program of counterterrorism interrogation. As has been discussed, effectiveness can appear deceptively simple when in fact it is enormously complex. Therefore, it is necessary to put forward the precise manner in which the testing of empirical validity will be carried out when discussing interrogation for counterterrorism. Building on the Oxford English Dictionary definition of efficacious (“that [which] produces, or is certain to produce, the intended or appropriate effect”), and the definition of torture found in Article 1 of the CAT treaty, efficacy in our context will mean: the purposeful infliction of severe pain or suffering on detained suspects, be it physical or mental, producing, or certain to produce, timely and reliable intelligence information for stopping attacks against noncombatants. In this context it is necessary for the elements of timeliness and reliability to be a part of this definition of efficacy because these are indeed a part of the “intended or appropriate effect.” Otherwise there will be the possibility that noncoercive methods would have provided the very same results. It is insufficient to claim that the acquisition of information that turns out to be true or useful at some later point in time is enough to demonstrate the efficacy of torture. For torture to be considered efficacious, it must be shown to be a superior technique.

Can torture of innocent or ill-informed individuals ever be considered to be effective? This essential question clarifies the inquiry of this chapter and helps explain the manifest international movement toward the comprehensive illegality of torture. Because the inherent nature of ill-treatment for intelligence-gathering obligates the use of unverifiable suspicions as a trigger for abuse, such a program will always include the innocent and ill-informed among its victims. It is impossible to know in advance (or afterwards) what is inside the head of a detainee, and therefore those who do not have the information we seek will inevitably be brought into the program. The result is that their torture leads to completely unpredictable outcomes coupled with the guaranteed abuse of human beings.

Because terrorism targets legitimacy, counterterrorism policies must be consciously designed with the knowledge that terrorist acts are meant to provoke a government into overreaching with an exercise of force deemed to be illegitimate. Violent force wielded on unchecked suspicion, ensuring that the innocent and ill-informed will be pulled into the program, is a surefire way to jeopardize legitimacy.

Also, we must distinguish between punishment for past crimes and the intention to prevent future ones. When we speak of the efficacy of torture in this chapter, it has nothing to do with the former and everything to do with the latter. Demonstrating agreement, former Vice President Dick Cheney gave a speech in 2009 discussing the security measures implemented when he was in office, and spoke to the intention behind using “enhanced interrogation techniques” (EITs). In the speech he made clear that the administration’s use of coercion was solely for intelligence-gathering purposes. While claiming that the tactic worked (without offering any evidence to back up the claim), Cheney propounded,

We know the difference in this country between justice and vengeance. Intelligence officers were not trying to get terrorists to confess to past killings; they were trying to prevent future killings. From the beginning of the program, there was only one focused and all-important purpose. We sought, and we in fact obtained, specific information on terrorist plans.

(Cheney 2009)

The defense of the institutionalization of a program of ill-treatment here was because information was gained “on terrorist plans.” The standard that is asked to be applied to the counterterrorist campaign was not that of imminent or timely plans, but just plans. This negligible hurdle does nothing to explain why torture should be chosen over other methods.

That torture could be known to be necessary to avert serious injury and death presents an onerous burden of proof that must lie on the shoulders of those who wish to subvert or change the comprehensive international and domestic ban on torture and ill-treatment. Because it is impossible to know that the information being sought to prevent harm actually exists within the mind of a proposed victim, or that coercion will actually extract it if it does exist therein, there is never any way of knowing that the use of ill-treatment will further that cause. If it were possible to know what is in the mind of a specific detainee, torture would in fact be unnecessary. The absurd claim is that we can know the mind of the proposed victim, but not in its entirety. This is an insurmountable hurdle simply created by the constraints of our humanity. One scholar on torture suggested, when speaking to the possibility of technological advancements providing a means to overcome such human limitations: “if such technology existed, it would surely be just as widespread as electricity” (see Rejali 2007: 453).

This chapter will be an investigation into the empirical validity of treatment during interrogation, and the intelligence gained thereof, by laying out the facts concerning six high-profile detainees. A host of government documents and official statements available in the public sphere will be analyzed which catalogue the suspicions, treatment, and level of cooperation of individuals who have been touted as important figures within the al-Qaeda organization. While these assumptions still held true, their capture and interrogation were lauded as advancements in the “war on terror.” However, we will see that the original assumptions frequently turned out to be erroneous, thus drastically recasting the efficacy of the program. The cases of the six detainees that will be presented here are those of (1) Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi, (2) Abu Zubaydah, (3) José Padilla, (4) Binyam Mohamed, (5) Mohammed al Qahtani, and (6) Khalid Shaykh Mohammed.

Former President George W. Bush still stands behind the value of the program of ill-treatment he authorized and even claims that he would do it again (Bush 2010: 168–171). Most importantly for our purposes, what will be clearly seen through the tracing of the known facts relating to these cases is that even when it came to dealing with the detainees considered to be the most valuable, the program still pulled in the innocent and ill-informed with a vetting process we must assume to be at its most rigorous.

Nonetheless, when it comes to discussing the ill-treatment of detainees in US military or intelligence-agency custody since 9/11, there are regrettably numerous cases that can be explored. Today it is possible to find a host of government and nongovernment reports providing extensive empirical data:

• report from the US Senate Armed Services Committee (2008);

• internal military reports such as the Taguba Report (Taguba 2008), the Church Report (Church 2005); and the Schmidt-Furlow Report (Schmidt and Furlow 2005);

• Inspector General reports from the CIA (2004) and the FBI (2008);

• leaked confidential reports from the ICRC (2004, 2007);

• nongovernmental reports from the Open Society Justice Initiative (2013); The Constitution Project (2013);

• accounts from interrogators at the scene (Soufan 2009, 2011); or

• investigative manuscripts from major book publishers (Mayer 2008).

All of these works detail prisoner abuse, and sometimes death, in both Afghanistan and Iraq, along with the ill-treatment and torture of a detainee in Guantánamo. The most recent (and, at 600 pages, most extensive) is the bipartisan Constitution Project, which broadcast its conclusion that it is “indisputable that the United States engaged in the practice of torture” (2013: 3). Of note, this investigation also dove into the question of efficacy and asserts a truism that also guides this study: “to say torture is ineffective does not require a belief that it never works; a person subjected to torture might well divulge useful information” (2013: 11).

There is also one government document treating this specific question of efficacy that has not yet come to light. The US Senate Intelligence Committee completed a 6,000-page report in 2012 that conducted a methodical assessment of whether EITs led to more intelligence breakthroughs or to false leads. While both of these reports are welcome and surely add to the empirical data on the subject, this chapter approaches the question from a different angle.

It was the broadcasting of graphic photographs exhibiting prisoner abuse in the Iraqi detention facility of Abu Ghraib that brought this issue to the fore of citizens’ minds (see Leung 2004). This began to demonstrate the extensive nature of the ill-treatment being meted out in the “war on terror.” However, this chapter will not attempt to detail the widespread abuse that infected many parts of the US detention system, but rather will focus on just one particular aspect—that is, torture must be carried out on suspicion, not on certain knowledge.

It is often accepted that in a single circumstance it is possible for the ticking bomb scenario to pose a daunting moral question for an individual. However, this is not the situation we will be dealing with here. It was an intelligence-gathering program based on suspicion and ungoverned by law that was initiated, and therefore the already grave problems of the certainty, targeting, immediacy, and effectiveness of coercive techniques were all multiplied exponentially.

Crucially, there is an angle on this ticking bomb scenario that is less often stressed; the application of torture for gaining intelligence will inevitably be based on suspicion. The scenario is often presented in a manner that conceals the importance or centrality of this point, and it is worthwhile to review some of them since they reveal this very point (Ginbar 2008: 379–386). In the nineteenth century, in a precursor of this scenario (but devoid of bombs), Jeremy Bentham put forward the philosophical question with a formulation that properly identifies the root of suspicion in this question. Bentham wrote:

Suppose an occasion, to arise, in which a suspicion is entertained, as strong as that which would be received as a sufficient ground for arrest and commitment as for felony—a suspicion that at this very time a considerable number of individuals are actually suffering, by illegal violence inflictions equal in intensity to those which if inflicted by the hand of justice, would universally be spoken of under the name of torture. […] To say nothing of wisdom, could any pretence be made so much as to the praise of blind and vulgar humanity, by the man who to save one criminal, should determine to abandon a 100 innocent persons to the same fate?

(Bentham 1804, cited in Ginbar 2008: 357; my emphasis)

In this scenario we find that there is an explicit recognition that the intentional application of severe physical or mental pain or suffering would be inflicted on the grounds of suspicion. While Bentham acknowledges this would be a high level of suspicion by which a court would find it sufficient to convict the detainee, the element of speculation which is inherent to all such scenarios is often glossed over. Additionally, it should be remembered that the level of evidence that would satisfy a court is quite diverse in different jurisdictions, and can even be said to differ with each judge and jury. Nevertheless, because we are speaking about what might or might not be found inside someone’s mind, we are without question discussing an unverifiable suspicion.

As such, in this chapter we shall delve into the facts that are known to address the sphere of empirical validity. Social science provides the most useful tools for ascertaining what techniques have or have not been effective in the past, but this discipline has been largely prevented from applying them to torture because governments have not allowed access to the raw data necessary for a full and objective assessment. It is also the case that historians have not been able to locate any reports produced on the effectiveness of torture for any government. As one thorough scholar on the subject has put it, “[t]hose who believe in torture’s effectiveness seem to need no proof and prefer to leave no reports” (Rejali 2007: 522). Due to the dearth of information on the subject, this chapter will analyze the empirical data that has become available on the use of brutal interrogation methods as implemented on six particular suspected terrorists in the “war on terror.”

The fact that proving torture to be superior has never been achieved, even after centuries of its use, is extremely telling. If there were conclusive empirical data showing its effectiveness, there would most likely not be such an unmistakable international movement toward torture’s prohibition without exception.

II Legality: the torture memos

It is the legal interpretation employed by the lawyers of the OLC, an office that assists the US Attorney General in his function as legal adviser to the President and all the executive branch agencies, that provides evidence of the efforts by the Bush administration to legally justify harsh interrogation techniques. Thus, a series of memoranda authored inside this office concerning the question of limitations on coercive interrogations became known as the “torture memos.” Those that fall under this name are primarily from the OLC, which provides interpretations of law that are legally binding on the executive branch, and have been claimed to effectively “immunize officials from prosecutions for wrongdoing” (Goldsmith 2007: 150).

While a comprehensive analysis of all of these legal documents is not within the scope of this study, there is a vital significance that can indeed be discerned for our questions of legitimacy and international law. Even a cursory reading of these memos reveals the extent to which any discussion of torture demanded a reference to international legal norms. Importantly, the Bush administration saw itself as obliged to analyze its own policies through international legality, since the CAT treaty required that this prohibition become a part of domestic law. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that average citizens were also going to be concerned that counterterrorism policies align with this applicable law. Thus, these torture memos show how international law has become intricately intertwined with the rule of law and the constraints on the legitimate use of force.

The most infamous document in this series is entitled “Re: Standards of Conduct for Interrogation under 18 USC §§2340–2340A,” known as the Bybee memo, though it was largely drafted by John Yoo and only signed by Jay Bybee. It was public reaction to photos of detainee abuse in the Iraq detention facility of Abu Ghraib that prompted the leak of this particular memo in June 2004. After the appalling images of widespread prisoner abuse by US soldiers and contractors hit the airwaves and newsstands, citizens of the United States began to piece together what had been reported in the nation’s leading newspapers since late 2002, and at times on their front pages. That is, a realization started to dawn that a different type of interrogation regime had been instituted and now governed the questioning of detainees in the global “war on terror.” With this national wince towards prisoner abuse in the face of incontrovertible photographic evidence, someone inside the government leaked the Bybee memo to the press, which sent out a signal that the coincidence between the treatment of detainees in Iraq and other reports from the “war on terror” had a common thread.

The reaction from commentators, law professors, and others in the legal community was highly critically of the level of professional work found in the Bybee memo. The Dean of the Yale Law School, Harold Koh, a member of the OLC during the Reagan administration and subsequently the Legal Adviser of the Department of State in the Obama administration, said on record before the Senate, “in my professional opinion as a law professor and a law dean, the Bybee memorandum is perhaps the most clearly legally erroneous opinion I have ever read” (cited in Dean 2005). A law professor at the University of Chicago said “It’s egregiously bad. It’s very low level, it’s very weak, embarrassingly weak, just short of reckless” (Liptak 2004).

While not all of the criticism was as harsh, the overall reaction of the legal community was negative. Best capturing this mood was a letter signed by nearly 130 lawyers, retired judges, law school professors, and a former director of the FBI, condemning the released memoranda and calling for an investigation into possible connections between the OLC opinions and the detainee abuse at the Abu Ghraib prison facility (Higham 2004: A04). Within a week of the appearance of the Bybee memo on the Washington Post website, the now unclassified memo was publicly vacated of its legal status (Goldsmith 2007: 156–165).

The Bybee memo largely captures where the interpretation of the legal obligations under the CAT stood as of August 2002, and it was under this legal regime that the most severe consequences from abusive interrogations began. What next happened behind closed doors was disturbing because neither the interim cosmetic memo, nor those that were to follow, did anything to pull back from the conclusions of allowable interrogation methods found in the August 2002 memos. Around the edges, the analysis became more scholarly, with additional attention on pertinent precedent, acknowledgment of contrary arguments, and an abandonment of the doctrine that allowed the President to bypass congressional legislation in wartime.

In May 2005, the lawyer who would later assume the permanent position as the head of the OLC, Steven Bradbury, issued three memos that reached even broader, more sweeping conclusions than before. This time, all of the authorized abusive techniques which were previously not believed to be torture were now found not to be so much as cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment. This conclusion, again meant to be kept secret, even included controlled drowning evoking death, also known as waterboarding.

The Bradbury memos (released by the Obama administration in 2009) arrive at that finding on the basis of two primary facts. The first is that US personnel subjected to many of the same techniques in the counter-torture training program Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape (SERE) have reportedly not experienced severe pain or suffering or prolonged mental harm (US Senate Armed Services Committee 2008: xii). Second, the fact that doctors would be present at the interrogations would permit them to stop the application of particular techniques if it were deemed that the threshold into prohibited treatment was going to be crossed.

Whether the previous application of certain techniques in an explicitly finite and voluntary environment or the presence of medical personnel charged with monitoring inherently subjective pain are enough to avoid legal liability for treaty violation will not be assessed here. Suffice it to say that reciprocity had no place in this analysis because the SERE program had already been explicitly built on preparing “American personnel to withstand interrogation techniques considered illegal under the Geneva Conventions” (US Senate Armed Services Committee 2008: xiii). Next, the idea that the US Government would accept such treatment of its own soldiers because of the presence of medically trained persons in a controlled environment appears dubious at best.

The Bradbury memo identified as the most egregious and problematic is entitled “Re: Application of United States Obligations under Article 16 of the Convention against Torture to Certain Techniques that May Be Used in Interrogation of High Value al Qaeda Detainees (Article 16 Memo)” (Bradbury 2005b). As Article 16 of the CAT treaty speaks specifically of ill-treatment that does not rise to the level of torture, this memo rightfully drew critical attention.

The most noteworthy criticism came from a former member of the Bush administration who had been engaged behind the scenes in push-back against the legal analysis found in these memos. Philip Zelikow worked on intelligence and terrorism issues for Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and gained access to the OLC opinions after they were issued in May 2005. Just after the Obama administration made a public release of related memos, Zelikow published an article (2009) detailing some of his own actions in response to an analysis that he found to be deeply flawed.

Because Zelikow was directly involved in working through the internal legal minutia on the interrogation program, his dissenting opinion (demonstrating a “legitimacy deficit”) is particularly useful here. The first point he makes is that the focus on waterboarding, used as an expedient to extract information in dire circumstances, distracted the public from the fact that what had developed was a program of interrogation intended to “disorient, abuse, dehumanize, and torment individuals over time” (Zelikow 2009). The detainee would be stripped naked, dowsed regularly with cold water, slapped around, thrown into hollowed walls, forced into cramped boxes, and shackled to the ceiling to force the prisoner into a standing position to be deprived of sleep for extended periods, before ever getting to the controlled drowning.

While Zelikow wrote that all of the memos “have grave weaknesses” (2009), he reserved his most severe condemnation for the Article 16 memo because it downgraded all of the previously authorized techniques (since they did not constitute “torture”) to being considered even less than cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment. This memo was deemed to be the “weakest of all” because of the specific legal knowledge Zelikow gained from working for many years on the jurisprudence of the US constitutional standard of “shocks the conscience:” the US constitutional standard prohibiting ill-treatment.

The US attached a reservation of understanding to the CAT treaty when it was ratified in 1994, saying that it would interpret Article 16 dealing with the lower forms of ill-treatment to mean the legal precedent found in constitutional law. This is of central importance to the Zelikow denunciation because this legal question became directly and completely intertwined with domestic constitutional law. This is why Zelikow took steps at that time, outside of his normal duties, to explicitly refute this Article 16 memo, which he believed presented a “distorted rendering of relevant US law” (Zelikow 2009). So, we again see that the ratification of an international treaty has been bolstered by the domestic jurisprudence giving the CAT further shape and meaning on the matter of ill-treatment.

As Zelikow understood the legal interpretation of the “shocks the conscience” standard, there was no way that these techniques could be deemed legal. He pointed out that the memo endorsed the absurd legal conclusion that “the methods and the conditions of confinement in the CIA program could constitutionally be inflicted on American citizens in a county jail” (Zelikow 2009). One must, in effect, argue that federal courts have ruled in the past, and could be reasonably expected to rule in the future, that US citizens can be stripped naked, slapped, handcuffed to the ceiling, and even subjected to controlled drowning. Zelikow, according to his study of the pertinent case law, did not believe this was in any way a reasonable argument.

b Pushback from the legislature and the judiciary

What must be understood about this series of secret memos is that, while their conclusions pushed even farther than before, the other branches of government were placing further clarified legal and public limits on interrogations. As discussed in Chapter 3, in 2005 the US Congress passed specific legislation concerning interrogation: the Detainee Treatment Act (DTA), 2005. This legislation contains provisions that require Department of Defense personnel to employ the US Army Field Manual guidelines while interrogating detainees, and it specifically prohibited the use of cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment or punishment. It is commonly known as the “McCain Amendment” since these provisions were added to the defense spending Bill via amendments introduced by Senator John McCain, who was tortured in detention during the Vietnam War. The overwhelming bipartisan support for the Bill when it passed in the Senate by a vote of ninety to nine suggested a new independence among Republicans to challenge the White House on counterterrorism policy.

There was also the landmark decision of Hamdan v. Rumsfeld which established, among other things, that Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions with its prohibition of ill-treatment was fully applicable to the “war on terror.” Thus, we find both the legislative and the judicial branches palpably pushing back against the executive on the issue of interrogation.

Also of importance is what happened when the legislation containing the McCain Amendment came across the desk of President George W. Bush. The Bill was indeed signed into law; however, attached to it was a “signing statement,” (an official document in which the President explains his interpretation of the new legislation), that brought into question the intention of the executive branch to enforce this new provision. In this signing statement, President Bush expressed that he would understand this new law “in a manner consistent with the constitutional authority of the President to supervise the unitary executive branch and as Commander in Chief and consistent with the constitutional limitations on the judicial power” (Bush 2006a).

While this statement may seem innocuous at first blush, particular attention should be focused on the terms “constitutional authority,” “unitary executive,” and “Commander in Chief.” The OLC had interpreted the President’s constitutional power in wartime as the commander in chief to be unassailable by the other branches of government. So, when we read that the President will interpret this new law in the context of a “unitary executive,” we must understand that he is saying that he will act in a manner that will leave the President’s action unfettered by this law which is meant to curtail and constrain his authority on interrogation techniques. While the concept of a “unitary executive” was once a relatively obscure theory of expanding and protecting presidential power, it gained significant ground during the George W. Bush presidency.

President Bush attached a host of signing statements (not a new invention by his office) to the legislation he signed over his years in office, but it was this instance that began to draw attention to this practice. In an act that can be described as real concern and dissent from civil society, the American Bar Association (ABA) appointed a task force to investigate the signing statements as a challenge to the constitutional structure of the US democracy. The conclusions were stark and grave, finding that the practice had become “contrary to the rule of law and our constitutional system of separation of powers” (ABA 2006: 1).

The reason why the rise of this issue of “signing statements” and the “unitary executive” within the public sphere is pertinent here is because the question of an abuse of power directly addresses the issue of legitimacy. In assessing the torture memos and the response to their public disclosure through the lens of legality, we see that serious troubles were exposed. The deep flaws in the Bybee memo were evidenced by its immediate retraction just after the public gained knowledge of it and began its outcry. This was followed by actions in Congress to pass legislation to place explicit constraints upon other forms of ill-treatment in Department of Defense interrogations. Additionally, the Supreme Court found Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions to be applicable law in the “war on terror,” furthering the legal constraint on interrogation. Despite these explicit moves by the other branches to curb what was considered to be an overreach, the administration proceeded in secret to provide legal cover for its actions. Yet, through the issue of signing statements, the sense of an illegitimate use of force or abuse of power was taking root in a growingly uneasy public.

c A flawed attempt at efficacy for legality

While it is clear that administration lawyers needed to push against international legality for extending coercive interrogation limits, the issue of efficacy also came to the fore. One purported relationship between legality and efficacy can be observed by the fact that the effectiveness of the applied coercive interrogations is treated quite extensively within this series of OLC memos themselves, in the legal analysis of the Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR) (US Department of Justice 2009: 96, 146–147, 158, 243–251, 259) and in the 2004 CIA Inspector General report (2004: 82–91). However, that this issue of efficacy has been widely analyzed in these documents does not mean there is a legal link between the concepts in the way it has been described in the memos. The CAT treaty and international courts have explicitly dismissed the use of balancing such competing interests. Rather, what we find in these documents represents a flawed analysis of a connection between legality and efficacy made particularly gross by the use of erroneous empirical data.

Both the OPR and the Inspector General reports identify the same three difficulties in arriving at an objective assessment of the applicable value of coercive interrogations. Using the exact same wording, they each assert that,

Measuring the overall effectiveness of EITs is challenging for a number of reasons including: (1) the Agency cannot determine with any certainty the totality of the intelligence the detainee actually possesses: (2) each detainee has different fears of and tolerance for EITs; (3) the application of the same EITs by different interrogators may have different results [redacted].

(CIA Inspector General 2004: 89; US Department of Justice 2009: 96)

In assessing the efficacy of ill-treatment during interrogation, we will continually return to the first element put forward here as it is a hurdle that cannot be surmounted under the conditions of humanity as understood today: we cannot know what is known.

It is the Article 16 memo authored by Stephen Bradbury that treats the issue of effectiveness most fully for the OLC, if only because he was forced to meet this argument as it was raised in the hyper-critical CIA Inspector General report. In this memo, Bradbury admits that “it is difficult to quantify with confidence and precision the effectiveness of the program” (2005b: 10). He refers to the report and the complexity of parsing the direct successes of the techniques employed but stresses the increased general knowledge gained on how al-Qaeda and its affiliates operate. Bradbury asserts that there has been “specific actionable intelligence” gained and additionally cites the CIA as having produced over 6,000 intelligence reports as a result of the authorized coercive techniques (2005b: 11).

However, one thing that must be noted in this memo by Bradbury is that, as he makes the best case he can for efficacy, there is absolutely no reference to any imminent threat being averted nor any other timely action of necessity. Although many who argue for the use of it point to coercion as the most time-efficient means in moments of a crisis, this lacuna in the government’s assessment of the interrogation program leaves open the possibility that the intelligence gained could have been obtained through other means.

a detainee who, until time of capture, we have reason to believe. (1) is a senior member of al-Qai’da or an al-Qai’da associated terrorist group […]; (2) has knowledge of imminent terrorist threats against the USA, its military forces, its citizens and organizations, or its allies; or that has/had direct involvement in planning and preparing terrorist actions against the USA or its allies, or assisting the al-Qai’da leadership in planning and preparing such terrorist actions; and (3) if released, constitutes a clear and continuing threat to the USA or its allies.

(Bradbury 2005b: 5; my emphasis)

Most important to note about this definition is the fact that the CIA uses the phrase “reason to believe” to qualify who will be considered a high-value detainee. This classification is not based on a verified, proven, or confirmed association or specific action.

However, for the use of the most extreme enhanced technique, water-boarding, even further criteria would need to be met. Among the authorized techniques, waterboarding drew the focus of the public’s attention for both legal and historical reasons. The technique has been legally considered as torture by the US throughout the twentieth century. This can be evidenced by the US experience in the Philippines at the turn of the century (where it was employed by soldiers, leading to courts martial), the Tokyo War Crimes trials that followed World War II, and the United States v. Lee case before the domestic courts in 1984 (Wallach 2007: 477). Yet this interrogation technique was placed in the CIA’s arsenal for the first time in the nation’s history in 2002, and Bradbury legally authorized it again.

The use of this controlled drowning necessitated a series of further conditions be met before it could be employed. The only circumstances under which it could be introduced align very closely with what is often thought to be the ticking bomb scenario:

credible intelligence that a terrorist attack is imminent; substantial and credible indicators that the subject has actionable intelligence that can prevent, disrupt or delay this attack; and other interrogation methods have failed to elicit the information [or] CIA has clear indications that other … methods are unlikely to elicit this information within the perceived time limit for preventing the attack.

(Bradbury 2005b: 5; original emphasis)

Most important, however, is that this document is from August 2004, after the EITs had already been employed and two months after the public disclosure of the Bybee memo. There is no indication that these qualifiers existed for restraining the use of the waterboard before this. Therefore, the use of controlled drowning was in fact employed without the above standards in place.

Also of importance, Bradbury relied on CIA documents, including a still undisclosed document from March 2005 entitled “Re: Effectiveness of the CIA Counterterrorist Interrogation Techniques” (effectiveness memo; cited in Bradbury 2005a: 8). Based primarily on this memo, Bradbury concluded in his analysis that the program had indeed been effective in producing important information including actionable intelligence. The Article 16 memo arrived at the conclusion that, due to the reservation attached to the CAT treaty by the US, the restriction on cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment would be punishment prohibited by the Fifth Amendment, since it was the part of the Bill of Rights which was applicable in this particular context.

Thus, the relevant standard was treatment that “shocks the conscience.” Bradbury interpreted this to mean that an action must not be “arbitrary in a constitutional sense,” or, more precisely, that an act must have “reasonable justification in the service of a legitimate governmental objective” according to his own reading of precedent (Bradbury 2005b: 2–3). To fulfill this legal requirement manufactured by Bradbury, enhanced interrogation techniques needed to be effective. To discern whether the action of waterboarding was constitutionally arbitrary, Bradbury relied on the effectiveness memo to establish that it furthered a government’s legitimate objective. He determined that preventing future terrorists attacks by al-Qaeda surely fulfilled the concept of a legitimate objective, and, since the technique was said to have worked in the CIA memo, the standard of furthering said objective was met.

However, not only was Bradbury’s legal analysis flawed, his uncritical reliance upon the effectiveness memo in order to conclude that EITs were successful was unjustified to boot. The most blatant problem was that there was patently false information found within the document that could easily have been crosschecked. This memo claimed that the techniques had directly led to the capture of an al-Qaeda suspect in May 2003. Considering that enhanced coercive questioning procedures were first authorized by the Bybee memo of August 2002, this was feasible. However, the suspect in question was actually apprehended with much public fanfare as the “dirty bomb” suspect, and an official announcement was made by Attorney General John Ashcroft from Moscow, where he was meeting with his counterpart officials. The suspect was taken into custody in May, and the pronouncement took place in 2002 (one year earlier). Therefore, it would be impossible, as the effectiveness memo claimed, for this capture to have resulted from intelligence gained from the EITs, as they had not yet been authorized (US Department of Justice 2009: 246–247). Such a gross error could easily have been caught by any of the memo’s original drafters, the attorney who relied on this claim, or any of the policy-makers touting it as a victory resulting from expanded tactics in interrogation. What is abundantly clear, however, is that the capture of this suspect was not the fruit of any authorized enhanced techniques.

Additionally, treated in another memo of the same month, the application of the specific technique of waterboarding is said to have often, if not always, “exceeded the limitations, conditions, and understandings recited in the Classified Bybee Memo and the Bradbury Memos” (US Department of Justice 2009: 247). In other words, the application of the waterboard did not stay inside its authorized limits. This is particularly troublesome because it is enormously problematic to claim to know the efficacy of a technique that was never applied in the manner specifically described and authorized. Bradbury was aware of these systematic excesses as he wrote his memos in the wake of the most devastating internal report on the CIA program of interrogation to that date. For this reason, Bradbury was forced to acknowledge this excess and address it head on in his legal analysis, if only in a footnote. He wrote:

The IG Report noted that in many cases the waterboard was used with far greater frequency, than initially indicated, and also that it was used in a different manner (“[t]he waterboard technique was different … from the technique described in the DoJ opinion and in the SERE training. The difference was in the manner in which the detainee’s breathing was obstructed. At the SERE school and in the DoJ opinion, the subject’s air flow is disrupted by the firm application of a damp cloth over the air passages; the interrogator applies a small amount of water to the cloth in a controlled manner. By contrast, the Agency interrogator … applied large volumes of water to a cloth that covered detainee’s mouth and nose. One of the psychologists/interrogators acknowledged that the Agency’s use of the technique is different from that used in the SERE training because it’s for real and is more poignant and convincing.”)

(Bradbury 2005a: 41, note 51; internal citations omitted)

Bradbury uses a citation from one of the psychologists who engineered the transfer of the SERE torture-resistance training to the CIA interrogation program, and somehow this is meant to bolster reasoning for the stark difference in application. However, this argument is clearly flawed. Serious weight was given to the claim that the techniques could not be construed as ill-treatment because they had been applied regularly to US personnel in the SERE program. If they were significantly different in their application to high-value detainees, regardless of the reason, this argumentation falls apart. The techniques cannot be acceptable because they have been applied to US personnel and at the same time warrant a different usage in real interrogations. The fact that the waterboard in this circumstance is “for real and is more poignant and convincing” means that it must be legally assessed as such.

Nonetheless, the CIA Inspector General report raised much graver issues which are certainly not dealt with by this psychologist/interrogator’s statement. The report spoke of serious concerns introduced by medical personnel which were fully available to Bradbury. In fact, this trouble was cited and treated by Bradbury in the same footnote. In the original report it reads:

OMS [CIA’s Office of Medical Services] contends that the reported sophistication of the preliminary EIT review was exaggerated, at least as it related to the waterboard, and that the power of this EIT was appreciably overstated in the report. Furthermore, OMS contends that the expertise of the SERE psychologist/interrogators on the waterboard was probably misrepresented at the time, as the SERE waterboard experience is so different from the subsequent Agency usage as to make it almost irrelevant.

(CIA Inspector General 2004: 21–22, note 26)

And of direct consequence to the issue of efficacy, the CIA report went on to state that “Consequently, according to OMS, there was no a priori reason to believe that applying the waterboard with the frequency and intensity with which it was used by the psychologist/interrogators was either efficacious or medically safe” (2004: 21–22, note 26).

To deal with the genuine disquiet with the drastic difference in the application of the waterboard, Bradbury worked with both the OMS concerns through personnel in that office and with a full copy of the internal CIA report. His conclusion was that careful consideration had “resulted in a number of changes in the application of the waterboard, including limits on the frequency and cumulative use of the technique” (Bradbury 2005a: 41, note 51; internal citations omitted). However, there continues to be a huge problem. While it certainly is more humane to reduce the frequency and intensity of the use of the waterboard, it does not in any way address the efficacy upon which Bradbury’s analysis relies. If the program produced results in the past (yet serious doubts have already been raised as to the veracity of this claim), it did so under different conditions. Bradbury cannot rely on the effectiveness memo and its conclusions for his legal analysis while at the same time instituting meaningful changes to the application of the waterboard. If the modifications are consequential, and he states them to be just that, then any evidence of previous efficacy is inapplicable.

The intriguing aspect of what we have found here in our analysis is the attempted integration or overlap of legality and efficacy. Even though the CAT treaty explicitly rules out exceptions, Bradbury saw fit to include it into his legal analysis. While this must be characterized as legally flawed, it also speaks to the profound draw that many feel toward wishing to calculate what could be the lesser evil. For Bradbury’s legal analysis, the facet of effectiveness was essential to his finding that a specific act did not “shock the conscience” and thus was not “constitutionally arbitrary.” What is most disturbing to find, however, is that Bradbury’s complete reliance upon the information he was provided with by the CIA had such palpable empirical weaknesses regarding the claims of the program’s efficacy. Thus, this dearth of valid evidence proving the program’s efficacy raises even further questions about his conclusions concerning the legality of the program, undermining a legal analysis that was flawed at its outset.

III Efficacy: six high-profile suspects

Social scientists have never been given access to the raw empirical data on the use of torture employed by a government, nor have historians uncovered documents that reveal a methodical tracking. Therefore, when exposing empirical validity we are left with what is to be found in this chapter: a fair-minded assessment of the public data. This means that we will delve into the documents on six high-profile detainees whose captures have been touted as individual victories in the “war on terror.” First, however, to establish that the analysis data in this chapter will not expose a distorted picture of what can be expected when a government authorizes a program of torture and ill-treatment, we will take a brief look at compiled empirical data from other campaigns employing torture.

The US has its own historical experience with the use of physical and psychological coercion for interrogation purposes, so it is pertinent to begin here. There are two CIA interrogation manuals that describe the use of coercive techniques for intelligence-gathering that now appear online: the Kubark: Counterintelligence Interrogation of 1963 and the Human Resources Exploitation Training Manual of 1983. Yet neither offers instruction in applying torture techniques nor suggests how to choose subjects for interrogation. In the mid-1960s, the CIA did run what was called the Phoenix Program during the Vietnam War, with the purpose of capturing, interrogating, and killing Vietcong operatives (Rejali 2007: 470–472).

The managers of the Phoenix Program left behind a unique database that documented their assessment of the reliability of the intelligence gathered, and the conclusions are revealing. The standard for confirming a target was simply three independent pieces of intelligence. Nevertheless, one important statistic that emerges is that 94 percent of those who were actually confirmed by this process to be Vietcong were able to elude capture or death. At the same time, 20 percent of those who never reached the level of being fully confirmed by three separate sources had been terminated by the action squads. This statistic alone—of the less suspicious being more likely to suffer than the highly suspicious—begins to illuminate the gross problems with authorizing such a program. Additionally, there were “at least” thirty-eight innocents for every actual Vietcong agent victimized, with the most conservative estimate being that 4.7 innocent individuals were killed for every member of the Vietcong successfully exterminated (Rejali 2007: 471).

It is also instructive to look at another historical case where a good deal of empirical data has been collected and analyzed concerning the application of torture: the battle of Algiers. French General Jacques Massu reestablished colonial authority in the capital city of Algeria in just seven short months after being given carte blanche to clear out the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) group that was employing terrorist tactics in an insurgency against the foreign power (Duquesne 2001: 69–78; see also Horne 1977: 183–207). While there are some who cite this case to silence critics of torture due to this simple fact, the archives on the war in Algeria are now partially open, and interrogators have written their biographies, revealing a more complete view of what happened in that armed conflict. A wider purview exposes a general failure to produce reliable information through torture.

It is important to note that this ostensibly successful military campaign did not apply a selective process to filter out the innocent. A wide net was cast in the center of Algiers. In the end, nearly 30 percent of the population of the Casbah (24,000 of 80,000 people) were taken into custody, with a great majority of them subjected to torture (80 percent of the men and 66 percent of the women) (Rejali 2007: 482). One historian of the conflict has claimed that 1,400 operators of the FLN had actually been assembled in Algiers (Horne 1977: 184). This means that, even if every member had been detained, there were still around 22,600 individuals who suffered from wrongful detention, with a great many of them also being tortured. When the figures are calculated, the French military was torturing nearly fifteen individuals in order to stumble upon one actual member of the insurgency. Looking at such astounding figures and analyzing the efficacy of torture, one historian wrote “From a purely intelligence point of view, experience teaches that more often than not the collating services are overwhelmed by a mountain of false information extorted from the victims desperate to save themselves from further agony” (Horne 1977: 205).