The ‘Three Certainties’ Test

The ‘three certainties’ test

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

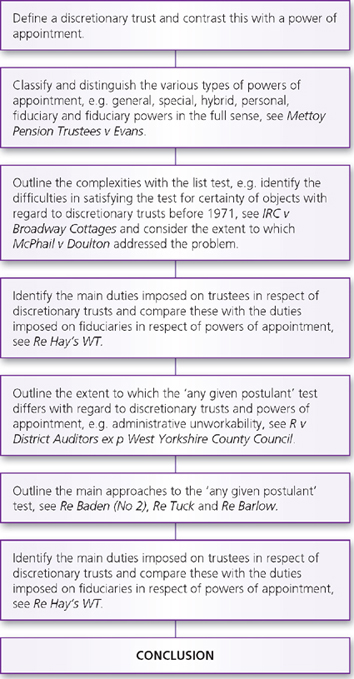

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

■ appreciate the distinctions between trusts and powers of appointment

■ understand the three certainties test and appreciate its significance in the creation of an express trust

■ comprehend, define and distinguish between linguistic (conceptual) and evidential uncertainty and administrative unworkability

■ recognise the various ways in which the courts have approached the ‘any given postulant’ test for certainty of objects

3.1 Introduction

The creation of an express trust may be achieved by one of two modes. The first involves the transfer of the relevant property to the trustees subject to a declaration of trust in favour of the beneficiaries (a transfer and declaration). The second mode requires the settlor to declare himself a trustee of the relevant property for the beneficiaries (self-declaration). It is of crucial importance that the transferor/settlor and the transferee/trustee recognise their obligations. The transferor/settlor loses all interests, as settlor, on the creation of the trust. He is treated as a complete stranger in regard to the trust property and is incapable, as settlor, of bringing or defending a claim concerning property subject to an express trust. The transferees, in this context, involve the trustees and the beneficiaries. These are the parties who are entitled to bring proceedings in respect of the trust property.

The importance to the trustees of ascertaining whether a trust has been created is in respect of their duties. The trustees are the individuals who have control of the property and are required to comply with their fiduciary responsibilities to avoid litigation for breach of trust. The beneficiaries acquire equitable interests in the property on the creation of the trust and are given a bundle of rights in order to protect their interests.

It is imperative that the parties to a trust are familiar with their respective duties and rights. Equally, the courts are required to apply a rational set of rules in order to determine whether a trust has been validly created or not. The courts have formulated a test to determine this question, known as the ‘three certainties’ test laid down by Lord Langdale MR in Knight v Knight [1840] 3 Beav 148:

JUDGMENT

| ‘First, if the words were so used, that upon the whole, they ought to be construed as imperative; secondly, if the subject of the recommendation or wish be certain; and thirdly, if the objects or persons intended to have the benefit of the recommendation or wish be also certain.’ |

Thus, the ‘three certainties’ are:

■ certainty of intention (words);

■ certainty of subject-matter;

■ certainty of objects (beneficiaries).

3.2 Certainty of intention

The requirement here is that the obligations of trusteeship are intended in respect of the property. This issue is determined by reference to all the circumstances of the case. Thus, oral and written statements, as well as the conduct of the parties, are construed by the courts to determine whether a trust relationship has been created.

3.2.1 Intention – a question of fact and degree

The test is a mixed subjective and objective issue, in that the focus of attention involves the settlor’s genuine intention as construed by the courts. The question is whether the settlor has manifested a present, unequivocal and irrevocable intention to create a trust. Oral statements, the conduct of the parties and documentary evidence, if any, will be construed by the courts. Accordingly the issue is whether objectively a trust was intended, by reference to the relevant facts of each case. The maxim ‘Equity looks at the intent rather than the form’ is applicable in this context. The word ‘trust’ need not be used but if used by the settlor is construed in its context. Alternative expressions will be construed by reference to the surrounding circumstances for the purpose of ascertaining whether the trust concept is intended. The doctrine of binding precedent is not applicable here and each case is determined on its own facts.

In Shah v Shah, the issue was whether a letter signed by a shareholder, coupled with the signing of a share transfer form, amounted to sufficiently clear evidence of an intention to create a trust.

CASE EXAMPLE

JUDGMENT

| ‘In interpreting a document, the court should not have regard to the subjective intention of its maker but to the intentions of the maker as manifested by the words he has used in the context of all the relevant facts. Here there is no doubt that Dinesh Shah (D) manifested an intention that the letter should take effect forthwith: see the words “as from today”. To give effect to those words, there has to be a disposition only of a beneficial interest since … legal title did not pass until registration … Judged objectively, did the words used convey an intention to give a beneficial interest there and then or an intention to hold that interest for Mr Mahendra Shah (M) until registration? Mr Dinesh Shah used the words “I am holding”, not, for example, the words “I am assigning” or “I am giving” and the concept that he holds the shares for Mahendra Shah until he loses that status on registration can only be given effect in law by the imposition of a trust. Accordingly Mr Dinesh Shah must be taken in law to have intended a trust and not a gift. Added to that … he calls the document “a declaration” in his letter, which is more consistent with its being a declaration of trust than a gift … it is not difficult to make a gift of shares but it may take time to complete the gift by registration of the shares in the donee’s name. One of the ways of making an immediate gift is for the donor to declare a trust. In my judgment that is what happened in this case.’ |

| Arden LJ |

3.2.2 Intention to benefit distinct from intention to create a trust

An intention to create a trust is fundamentally different from the broader concept of an intention to benefit another simpliciter. There are many modes of providing a benefit to another, such as gifts, exchanges and sales of property. But the requirement here is whether the settlor intended to benefit another solely by creating a trust. The trust mode of providing a benefit concerns a specific and ancient regime. The trust involves the separation of the legal and equitable interests and imposes fiduciary duties on the trustees with correlative rights in the hands of the beneficiaries. Decided cases are used merely for illustrative purposes.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Jones v Lock [1865] LR 1 Ch App 25 | |

| Robert Jones placed a cheque for 900 (drawn in his favour) into the hand of his nine-month-old baby, saying ‘I give this to baby and I am going to put it away for him.’ He then took the cheque from the child and told his nanny: ‘I am going to put this away for my son.’ He put the cheque in his safe. A few days later, he told his solicitor: ‘I shall come to your office on Monday to alter my will, that I may take care of my son.’ He died the same day. The question in issue was whether the cheque funds belonged to the child or to the residuary legatees under Robert Jones’s will. Held: (a) No valid gift of the funds was made in favour of the child, for the funds were not paid over to him. (b) No trust had been declared in favour of the child, for Robert Jones had not made himself a trustee for his child. | ||

JUDGMENT

| ‘[T]he case turns on the very short question whether Jones intended to make a declaration that he held the property in trust for the child; and I cannot come to any other conclusion than that he did not. I think it would be a very dangerous example if loose conversations of this sort, in important transactions of this kind, should have the effect of declarations of trust.’ |

| Lord Cranworth LC |

Likewise, in the unusual case of Duggan v Full Sutton Prison, The Times, 13 February 2004, the court decided that no trust was created. In this case the claimant, a serving prisoner, contended that a trust was imposed on a prison governor to retain as a trustee and invest cash sums surrendered by prisoners. The Court of Appeal decided that only a debtor/creditor relationship had been created and it would have been impractical to impose a trust relationship on the prison authorities.

In Paul v Constance [1977] 1 WLR 527, CA, the court considered the oral statements and conduct of the parties and concluded that there was sufficient evidence of an intention to create a trust. The court, however, acknowledged that this was a borderline case because it was not easy to pinpoint the specific time of the declaration of trust.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Paul v Constance [1977] 1 WLR 527, CA |

| Ms Paul and Mr Constance lived together as man and wife. Mr С received 950 compensation for an industrial injury and both parties agreed to put the money in a deposit account in Mr C’s name. On numerous occasions, both before and after the opening of the account, Mr С told Ms P that the money was as much hers as his. After Mr C’s death, Ms P claimed the fund from Mrs C, the administrator. Held: Mr C, by his words and deeds, declared himself a trustee for himself and Ms P of the damages. Accordingly, 50 per cent of the fund was held upon trust for Ms P. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘In this court the issue becomes: was there sufficient evidence to justify the judge reaching that conclusion of fact? When one looks to the detailed evidence to see whether it goes as far as that – and I think that the evidence does have to go as far as that – one finds that from the time that Mr Constance received his damages right up to his death he was saying, on occasions, that the money was as much the plaintiff’s as his. [The words] This money is as much yours as mine, convey clearly a present declaration that the existing fund was as much the plaintiff’s as his own. The judge accepted that conclusion. I think he was well justified in doing so and, indeed, I think he was right to do. It might, however, be thought that this was a borderline case, since it is not easy to pinpoint a specific moment of declaration … The question … is whether in all the circumstances the use of those words on numerous occasions as between Mr Constance and the plaintiff constituted an express declaration of trust. The judge found that they did. For myself, I think he was right so to find.’ |

| Scarman LJ |

An express trust may be successfully created in a commercial context before a company becomes insolvent. Insolvency involves claims from creditors, both secured and unsecured, but with the prospect of some creditors receiving very little funds or nothing from a sale of the company’s assets, the temptation to claim the existence of a trust of the company’s funds may prove attractive. The trust concept was successfully employed in Re Kayford Ltd [1975] 1 All ER 604, HC.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Kayford Ltd [1975] 1 All ER 604, HC |

| A mail-order company received advice from accountants as to the method of protecting advance payments of the purchase price or deposits for goods ordered by customers. The company was advised to open a separate bank account to be called ‘Customer Trust Deposit Account’ into which future sums of money received for goods not yet delivered to customers were to be paid. The company accepted the advice and its managing director gave oral instructions to the company’s bank but, instead of opening a new account, a dormant deposit account in the company’s name was used for this purpose. A few weeks later the company was put into liquidation. The question in issue was whether the sums paid into the bank account were held upon trust for customers who had paid wholly or partly for goods which were not delivered or whether they formed part of the general assets of the company. Held: A valid trust had been created in favour of the relevant customers in accordance with the intention of the company and the arrangements effected. The position remained the same even though payment was not made into a separate banking account. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘[I]t is well settled that a trust can be created without using the words trust or confidence or the like: the question is whether in substance a sufficient intention to create a trust has been manifested. The whole purpose of what was done was to ensure that the moneys remained in the beneficial ownership of those who sent them, and a trust is the obvious means of achieving this. No doubt the general rule is that if you send money to a company for goods which are not delivered, you are merely a creditor of the company unless a trust has been created. The sender may create a trust by using appropriate words when he sends the money (though I wonder how many do this, even if they are equity lawyers), or the company may do it by taking suitable steps on or before receiving the money. If either is done, the obligations in respect of the money are transformed from contract to property, from debt to trust.’ |

| Megarry VC |

In Re Ahmed & Co [2006] EWHC 480 (Ch), the High Court decided that a trust was created where the Law Society was obliged to create a fund to hold moneys when exercising its regulatory powers over solicitors. The funds were held on trust for the Society’s statutory purposes and for the benefit of those entitled to the moneys.

Similarly, a trust may be created between two parties in order to promote a commercial venture in circumstances where the parties did not have the capacity to transfer property to each other by way of a contract. The trust property may take the form of a chose in action, i.e. an intangible personal property right. This was the approach of the court in Don King Productions Inc v Warren [1999] 2 All ER 218, CA.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Don King Productions Inc v Warren [1999] 2 All ER 218, CA |

| The claimant, Don King Productions Inc (DKP), was owned by Don King, the leading boxing promoter in the USA. The first defendant, Frank Warren (W), was the leading boxing promoter in the UK. The other defendants were Mr Warren’s business associates. In 1994, the parties entered into two partnership agreements intended to deal with the boxing, promotion and management interests of the two promoters. One of the agreements declared that the two parties would hold all promotion and management agreements relating to the business for the benefit of the partnership. Some of the promotion agreements contained non-assignment clauses. But none of the agreements contained a prohibition on the partners declaring themselves as trustees. The issue before the court was whether the benefit of the promotion and management agreements was capable of being the subject-matter of a trust, despite the express clause prohibiting the assignment of rights. Held: A valid trust of a chose in action was created in favour of the claimant. This was created in accordance with the intention of the parties. Accordingly, W’s entry into the ‘multi-fight agreement’ intended for his benefit was in breach of the duties owed to the claimant. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘In principle, I can see no objection to a party to contracts involving skill and confidence or containing non-assignment provisions from becoming trustee of the benefit of being the contracting party as well as the benefit of the rights conferred. I can see no reason why the law should limit the parties’ freedom of contract to creating trusts of the fruits of such contracts received by the assignor or to creating an accounting relationship between the parties in respect of the fruits.’ |

| Lightman J |

In Charity Commission for England and Wales v Framjee [2014] EWHC 2507, Henderson J referred to a number of factors that may give rise to a trust. These are as follows:

JUDGMENT

| ‘(a) In order for a trust to be established, it is not necessary for a settlor to use the word “trust” or any other formal language, or to have any knowledge of trusts law, so long as the traditional “three certainties” (of words, subject-matter and objects) are satisfied, see Paul v Constance [1977] 1 WLR 527. (b) Where money is transferred to a recipient to be paid to a third party, and that money is not intended to be at the free disposal of the recipient, it is likely that a trust will arise, per Lord Millett in Twinsectra Ltd v Yardley [2002] UKHL 12. (see Chapter 8). (c) Although not a pre-requisite, if there is a requirement for the money to be held by the recipient in a separate account, that will be a strong pointer in favour of the existence of a trust, per Lord Millett in Twinsectra Ltd v Yardley. (d) The court is more likely to find that a trust was intended in a charitable context than in a commercial context, per Brightman J in Jones v AG (9 November 1976) unreported. (e) Whether the trust is an express trust for a third party, or a Quistclose trust (1970) (see Chapter 7) in favour of the transferor with a power to apply the money in accordance with the stated purpose, will depend in particular upon whether it was contemplated that there was a real risk that the purpose for which the money was paid might fail.’ |

| Henderson J |

In Charity Commission for England and Wales v Framjee [2014] EWHC 2507, the High Court decided that the operations of a website by a charity inviting donors to make contributions to charities of their choice, created express trusts in favour of the nominated charities. Members of the public who contributed to the charitable website organisation entered into binding contractual relations with that organisation that imposed fiduciary obligations to transfer the funds to named charities thus creating trust obligations along the lines of Quistclose trusts in favour of the intended charities.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Charity Commission for England and Wales v Framjee [2014] EWHC 2507 (HC) |

| The applicant, Charity Commission sought a declaration and directions concerning donations by members of the public to an unincorporated charity called the Dove Trust. The claim was brought against the interim manager, Mr Framjee. The Dove Trust operated a website which invited members of the public to make donations to charities of their choice. Following complaints, the Charity Commission initiated an inquiry and on 6 June 2013 an interim manager was appointed. No distributions were made to recipients after 6 June but the charity received further donations. The issues before the court were to determine the status of the receipts in the accounts of the Dove Trust and the mode of distribution of the remaining funds. The High Court relied on the principles laid down by Lord Millett in Twinsectra v Yardley [2002] 2 All ER 377, and decided that the donations were subject to contracts along the Quistclose lines which imposed fiduciary duties on the officers of Dove Trust. Accordingly, the surplus funds were held on trust in favour of the intended charities to be distributed on a pro rata basis. The beneficiaries suffered a common misfortune for which they were not responsible and were required to be treated pari passu. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘It seems clear to me that the donations, once received by the Dove Trust, were subject to a trust, and were not merely the subject of contractual obligations. At this point I find the observations of Lord Millett in Twinsectra compelling. |

| It is unconscionable for a man to obtain money on terms as to its application and then disregard the terms on which he received it. Such conduct goes beyond a mere breach of contract … The duty is not contractual but fiduciary. It may exist despite the absence of any contract at all between the parties … and it binds third parties as in Quistclose case itself. The duty is fiduciary in character because a person who makes money available on terms that it is to be used for a particular purpose only and not for any other purpose thereby places his trust and confidence in the recipient to ensure that it is properly applied. This is a classic situation in which a fiduciary relationship arises, and since it arises in respect of a specific fund it gives rise to a trust. | |

| The trustees came under a fiduciary duty to ensure that each donation would be used only for the purpose specified by the donor, because those were the terms on which the donation had been solicited. There is no reason in principle why a single transaction cannot give rise to both a trust and a contract. As Lord Wilberforce said in Quistclose Investments v Rolls Razors [1970] AC 567, there is “no difficulty in recognizing the co-existence in one transaction of legal and equitable rights and remedies.” See too Twinsectra. Thus the existence of a trust in the present case does not preclude the simultaneous existence of a contract between the donor and the trustees of the Dove Trust.’ | |

| Henderson J |

Counsel for the claimants contended that each donation of funds had created separate trusts with the effect that there were a multitude of charitable trusts created by each donor. The court rejected this argument as unnecessarily complex and instead decided that establishment of the website inviting donations to charitable bodies created a sub-trust within the Dove Trust. The justification for this analysis was declared by Henderson J in the following manner:

JUDGMENT

| ‘The attraction of such an analysis, it seems to me, is that it makes due allowance for the important fact that the Dove Trust was an established charitable trust with general objects when the website was established, and the fact that it was the Dove Trust to which donations were made. Against that background, an analysis which posits the creation of a multitude of separate trusts, each of which has a separate settlor and is wholly divorced from the terms of the Trust Deed, strikes me as unnecessarily complex … I prefer to view that trust as a global sub-trust established by the trustees under the aegis of the Dove Trust itself, and not as an arrangement which gave rise to literally thousands of wholly separate trusts.’ |

| Henderson J |

3.2.3 Precatory words

These are extremely ambiguous expressions used in wills, such as expressions of hope, desire, wish, recommendation or similar expressions which impose a moral obligation on the transferee. The issue here is whether such words impose a legal obligation on the recipient of property. For instance, a testator declares in his will: ‘I leave all my property to my widow feeling confident that she will act fairly towards our children in dividing the same.’ Did the testator create a trust?

‘Make sure you know the basics well enough in order to read further around the subject.’ Gayatri, University of Leicester

The position today is that such words may or may not create a trust, depending on the wording of the will and surrounding circumstances. There was a time during the development of the law of trusts when such words did not impose a trust, with the effect that the executor of the will was entitled to retain the property beneficially. This was the approach of the ecclesiastical courts. When the Court of Chancery was formed, it was believed that the solution allowing the executor to take the property beneficially was unacceptable. Thus, the Court of Chancery made strenuous efforts to avoid such a conclusion and decided that precatory words artificially created trusts (precatory trusts). The introduction of the Executors Act 1830 declared that the executor will be entitled to an interest under the testator’s will, if this accords with the clear intention of the testator. This paved the way for the modern approach to precatory words, namely to construe them in their context of the will and surrounding circumstances.

In Re Adams and Kensington Vestry [1884] 27 Ch D 394 the court decided that on construction of the words used in the will, no trust was intended.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Adams and Kensington Vestry [1884] 27 Ch D 394 |

| A testator left his property by will ‘unto and to the absolute use of my wife … in full confidence that she will do what is right as to the disposal thereof between my children’. The issue was whether a trust had been created. Held: No trust had been created for the children, so the wife was entitled to the property absolutely. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘[C]onsidering all the words which are used, we have to see what is their true effect, and what was the intention of the testator as expressed in his will. In my opinion, here he has expressed his will in such a way as not to shew an intention of imposing a trust on the wife, but on the contrary, in my opinion, he has shewn an intention to leave the property, as he says he does, to her absolutely.’ |

| Cotton LJ |

A similar conclusion was reached in Lambe v Eames [1871] 6 Ch App 597.

In contrast, in Comiskey v Bowring-Hanbury [1905] AC 84 the court concluded that on construction of the facts of the case, a trust was intended by the testator.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Comiskey v Bowring-Hanbury [1905] AC 84 |

| The testator transferred his property by his will to his widow, subject to the following terms: | |

| in full confidence that she will make such use of it as I should have made myself and that at her death she will devise it to such one or more of my nieces as she may think fit and in default of any disposition by her thereof by her will. I hereby direct that all my estate and property … shall at her death be equally divided among the surviving said nieces. | |

| The widow asked the court to determine whether she took the property absolutely or subject to a trust in favour of the nieces. Held: The intention of the testator was to transfer the property absolutely to his widow for life and, after her death, one or more of his nieces was or were entitled to benefit, subject to a selection by his widow. Failing such selection, the nieces were entitled equally. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘[E]ven if you treat the words in confidence as only expressing a hope or belief, the will would run thus: I hope and believe that she will give the estate to one or more of my nieces, but if she does not do so, then I direct that it shall be equally divided between them. I think that is a perfectly good limitation. The true antithesis I think is between the words such one or more of my nieces as she may think fit and the words equally divided between my surviving said nieces.’ |

| Lord Davey |

3.2.4 Effect of uncertainty of intention

Where the intention of the transferor is uncertain as to the creation of a trust, no express trust is created. The person who is in control of the property is entitled to retain it beneficially. Accordingly, if the transferor disposes of the property to the transferee and no trust is intended, the transferee takes it beneficially. Thus, in Re Adams and Kensington Vestry [1884] the testator’s widow was entitled to the property absolutely, and in Jones v Lock [1865], because of a failure to transfer the property the deceased’s estate was entitled to the 900.

KEY FACTS

| Certainty of intention | |

| Question of fact | Whether the settlor’s words and conduct indicate an irrevocable intention to create a trust | Re Kayford [1975]; Paul v Constance [1977]; contrast Jones v Lock [1865]; Duggan v Gov of Full Sutton Prison [2004] |

| Precatory words | Comiskey v Bowring-Hanbury [1905]; contrast Lambe v Eames [1871]; Re Adams and Kensington Vestry [1884] | |

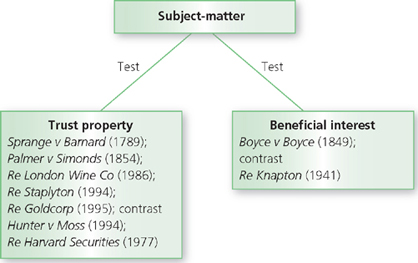

3.3 Certainty of subject-matter

The term ‘subject-matter’, on its own, is ambiguous and inherently deals with two concepts: namely the trust property and the beneficial interest. Although the same test is applicable to both, it is important to distinguish each type of uncertainty. If the trust property is uncertain because the settlor did not specify it with sufficient clarity, the intended trust will fail. This has a reflex action on the transferor’s intention, with the effect that the transferee retains the property beneficially. For instance, if A transfers 50,000 ВТ plc shares to X to hold ‘some’ of the shares upon trust for Y, the intended trust will fail and X will retain the property beneficially. This is because A has abandoned all interest in the property.

On the other hand, where the trust property is certain but the beneficial interest is uncertain, although the intended express trust will fail, a resulting trust for the transferor will arise. Thus, the legal owner will be required to hold the property on implied trust for the transferor. For instance, A transfers 50,000 BP plc shares to X on trust to provide some of the shares for Y and the remainder of the shares on trust for Z. The trust property is certain (50,000 shares), but the beneficial interest is uncertain, i.e. the number of shares to be held on trust for Y and the balance on trust for Z. The effect is that X cannot take the property beneficially and is required to hold on resulting trust for A.

The test for certainty of subject-matter is whether the trust property and the beneficial interests are ascertained or are ascertainable to such an extent that the court may attach an order on the relevant property or interest. This is a question of law for the judge to decide and this issue is determined objectively.

3.3.1 Certainty of trust property

The issue here is whether the property that is subject to the trust is capable of satisfying the test for certainty. The determining factor is whether the formula or mode of ascertainment of the trust property specified by the settlor is sufficiently precise to enable the courts to identify the trust property.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Sprange v Barnard [1789] 2 Bro CC 585 |

| A testatrix transferred property by her will to Thomas Sprange for his sole use, and added that at his death the remaining part of what was left that he did not want for his own use was to be divided equally between two named persons. The court decided that Thomas Sprange was not a trustee, and took the property beneficially. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘[T]he question is whether he may not call for the whole; and it seems to be perfectly clear on all the authorities that he may. It is contended that the court ought to impound the property; but it appears to me to be a trust which would be impossible to be executed. I must, therefore, declare him to be absolutely entitled to the 300, and decree it to be transferred to him.’ |

| Lord Arden |

The following examples illustrate the approach of the courts and highlight the principle that each case is to be determined by reference to its own facts.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Sheldon and Kemble [1885] 53 LT 527 |

| A testator bequeathed, in substance, all his real and personal estate to his wife, but added the desire that, at her death, what might remain of his property should be equally divided among his surviving children. The issue involved the nature and extent of the interest that was acquired by the widow and consequently the children. Held: The court decided that the children were entitled equally to the property on the death of the widow. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘If there is any sort of ambiguity, the court ought to adopt that construction, which most effectively regards the testator’s intention, reading the whole will together.’ |

| Kay J |

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Jones [1898] 1 Ch 438 |

| A testator gave all his property to his wife ‘for her absolute use and benefit, so that during her lifetime … she shall have the fullest power to sell and dispose of my said estate absolutely. After her death, as to such parts … as she shall not have sold or disposed of … I give devise and bequeath unto my brother … and to my wife’s sister … upon trust to … divide’ among certain persons. The question in issue was whether the widow took an absolute interest or enjoyed the interest for life. Held: On construction of the will the widow acquired an absolute interest in the testator’s real and personal estate. Byrne J discussed the rules of construction of wills: | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘It is clear that if a gift is made in terms to a person absolutely, that can only be reduced to a more limited interest by clear words cutting down the first estate. There is a principle also … that although the words are absolute in the first instance, you may find subsequently occurring words sufficiently strong to cut down the first apparent absolute interest to a life interest.’ |

The court came to a different conclusion in the Estate of Last. The approach adopted by the court was to construe the will of the testatrix by reference to the wording of the will and surrounding circumstances. If it was clear, based on an objective view of the evidence, that the testatrix intended the claimants to inherit an interest, the court will give effect to that intention.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Estate of Last [1958] P 137 |

| A testatrix disposed of her estate by a will in the following terms: ‘I give and bequeath unto my brother … All property and everything I have money and otherwise. At his death anything, that is left, that came from me to go to my late husband’s grandchildren.’ The brother duly proved the will and died intestate leaving no persons interested on his intestacy. The husband’s grandchildren claimed the relevant property on the death of the testatrix’s brother on the ground that the latter had only a life interest with remainder in favour of the claimants. The Treasury Solicitor opposed the application and argued that the estate was acquired by the brother absolutely and may be taken by the Crown on a bona vacantia. Held: On construction of the will as a whole and the surrounding circumstances the intention of the testatrix was sufficiently clear to cut down the brother’s interest from an absolute to a life interest and the claimants were entitled to the estate in equal shares on the death of the testatrix’s brother. | |

JUDGMENT

| The testatrix was very unlikely to have wished to benefit the Crown by the will, and that, therefore, the court should lean against a construction which would produce a result wholly inconsistent with the testatrix’s wishes. It may well be that the testatrix did not intend the Crown to be the object of her testamentary bounty. It may be even more likely that such a possibility never even entered her mind. But if the true construction of this will warrants the conclusion that it gave the whole estate to T. G. Cotton absolutely [the testatrix’s brother], I cannot avoid such a conclusion only because it may produce a result which the testatrix did not clearly foresee and may not at all have desired. I find the difficulty stems from the use of the words anything that is left. But for the introduction of these words I should have felt little difficulty in deciding that the testatrix intended to give a life interest only to T. G. Cotton. But the introduction of these words does not prevent the cutting down of an absolute interest to a life interest if the will itself supports such a construction. In this case, looking at the will as a whole, I have come to the conclusion that the words used are sufficiently clear to cut down T. G. Cotton’s interest from an absolute to a life interest. Clearly there is an ambiguity, but I have attempted to read the will as a whole, and then to reach that construction which most effectively, in my view, expresses the intentions of the testatrix. Weight may be given to the consideration that it is better to effectuate than to frustrate the testator’s intentions.’ |

| Karminski J |

CASE EXAMPLE

| Palmer v Simmonds [1854] 2 Drew 221 |

| A transfer by will to Thomas Harrison declared that, subject to a number of stipulations, he should leave the bulk of this property by will equally to four named persons. The court decided that no trust was intended and Thomas Harrison acquired the property beneficially. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘What is the meaning then of bulk? When a person is said to have given the bulk of his property, what is meant is not the whole but the greater part, and that is in fact consistent with its classical meaning. I am bound to say she has not designated the subject as to which she expresses her confidence; and I am therefore of the opinion that there is no trust created; that Harrison took absolutely, and those claiming under him now take.’ |

| Kindersley VC |

In the context of insolvency law it may be advantageous for some creditors to promote the trust concept in an effort to gain priority over the other creditors. On an insolvency or liquidation the company’s assets are available to pay its creditors. If a claimant is successful in establishing that some of the company’s assets are subject to a trust these assets will not be available for distribution to its creditors. Such trust assets belong to the beneficiaries and not the company. The success of such a claim varies with the facts of each case.

In Macfordan Construction Ltd v Brookmount Erostin Ltd, the Court of Appeal decided that the failure to carry out a contractual obligation imposed on a property developer to set up a retention fund for the benefit of a building company was insufficient to constitute a trust in favour of the building company. An equitable interest in a notional fund involving the property developer’s assets could not have been created when the company went into liquidation.

CASE EXAMPLE

| MacJordan Construction Ltd v Brookmount Erostin Ltd, The Times, 29 October 1991, CA |

| A building contract provided for interim payments to be made against interim architects’ certificates but entitled the developer to make a retention of 3 per cent from each certified amount. By January 1991 the retentions made by the developer amounted to 109,247 but no fund was appropriated and set aside by the developer. The company suffered financial difficulties and a receiver was appointed. On 4 March 1991 the bank’s floating charge crystallised. The builder argued that a trust had been created in its favour in a notional fund, which ranked in priority of the bank’s interest under its floating charge because the building contract pre-dated the charge. The court decided that the contractual right did not relate to any specific asset impressed with a trust and therefore the claim failed. The short answer to the builder’s claim was that it had no equity as against the bank to require the bank to make available assets over which the bank had an equitable interest under the charge simply because no identifiable asset was created in favour of the building company. | |

A similar result was reached in Re London Wine Co because property in the goods had not passed to the claimant. There was no means of identifying which property was acquired by the claimant from the mass of similar property in the possession of the company before its liquidation.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re London Wine Co Ltd [1986] PCC 121 |

| Customers bought wine from a wine company and contracted with the company to store the wine in its warehouse. On a liquidation of the company these customers claimed that a trust existed in their favour. The court decided that no property passed to the customers under the Sale of Goods Act 1979 because the customers’ goods were not separated from the bulk and no valid trust was created because of uncertainty of trust property. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘It seems to me any such trust must fail on the ground of uncertainty of subject-matter. It seems to me that in order to create a trust it must be possible to ascertain with certainty not only what the interest of the beneficiary is to be but to what property it is to attach. A farmer could, by appropriate words, declare himself to be a trustee of a specified proportion of his whole flock and thus create an equitable tenancy in common between himself and the named beneficiary, so that a proprietary interest would arise in the beneficiary in an undivided share of all the flock and its produce. But the mere declaration that a given number of animals would be held upon trust could not, I should have thought, without very clear words pointing to such an intention, result in the creation of an interest in common in the proportion which that number bears to the number of the whole at the time of the declaration. And where the mass from which the numerical interest is to take effect is not itself ascertainable at the date of the declaration, such a conclusion becomes impossible. In the instant case, even if I were satisfied on the evidence that the mass was itself identifiable at the date of the various letters of confirmation I should find the very greatest difficulty in construing the assertion that you are the sole and beneficial owner of 10 cases of such and such a wine as meaning or being intended to mean you are the owner of such proportion of the total stock of such and such a wine now held by me as 10 bears to the total number of cases comprised in such stock.’ |

| Oliver J |

The principle in Re London Wine was applied in Re Staplyton Fletcher [1994] 1 WLR 1181 (wines kept in warehouses) and Re Goldcorp Exchange Ltd [1995] 1 AC 74 (gold bullion purchased by customers but retained by a broker). The Sale of Goods (Amendment) Act 1995 introduced a significant change in the law. The position today is that multiple purchasers of goods are deemed to acquire interests as tenants in common in the subject-matter.

Where the trust property consists of shares, or property other than goods which is indistinguishable, the quantification of the interest on its own may be sufficient to satisfy the test. Thus, one fully paid-up ВТ plc share is the same as any other ВТ share of the same description. There may be no need to identify the relevant property by means of the share certificate numbers.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Hunter v Moss [1994] 1 WLR 452 |

| The defendant declared himself trustee for the claimant of 5 per cent of the issued share capital of a company. (One thousand shares of one denomination were issued.) The issue was whether the test for certainty of trust property was satisfied even though the defendant did not identify the share certificate numbers of the relevant shares. The court held that a valid trust was created. | |

Dillon LJ referred to the case of Re London Wine [1986] and distinguished it thus:

JUDGMENT

| ‘It seems to me that that case is a long way from the present. It is concerned with the appropriation of chattels and when the property in chattels passes. We are concerned with a declaration of trust, accepting that the legal title remained in the defendant and was not intended, at the time the trust was declared, to pass immediately to the plaintiff. The defendant was to retain the shares as trustee for the plaintiff. … just as a person can give, by will, a specified number of his shares of a certain class in a certain company, so equally, in my judgment, he can declare himself trustee of 50 of his ordinary shares in MEL or whatever the company may be and that is effective to give a beneficial proprietary interest to the beneficiary under the trust. No question of a blended fund thereafter arises and we are not in the field of equitable charge.’ |

A similar result was reached by the High Court in Re Harvard Securities Ltd, The Times, 18 July 1997, in respect of shares sold to clients but retained by nominees on their behalf.

3.3.2 Beneficial interests

Where the trust property is certain, but the interest to be acquired by the beneficiaries is uncertain, the express trust will fail and the property will be held on resulting trust for the transferor. This may be the case where the trustees acquire the trust property but some individual is required to divide the property between two or more beneficiaries. If that individual fails to allocate the relevant portions to the respective beneficiaries, and the issue cannot be resolved by the courts, the intended express trust will fail, thus giving rise to a resulting trust. This is the position where the settlor imposes a personal obligation on an individual to specify the relevant interests to be acquired by the beneficiaries.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Boyce v Boyce [1849] 16 Sim 476 |

| A testator devised two houses to trustees on trust to provide one for Maria, whichever she might choose, and the other to Charlotte. Maria died before the testator and had failed to make a selection. The question in issue was whether Charlotte might acquire one of the properties. The court decided that a personal obligation to select was imposed on Maria. No other person could have made the selection and the intended express trust failed but a resulting trust was set up for the testator’s estate. However, if no mode of distribution is provided in the trust instrument, the court may resolve the difficulty by adopting an arbitrary but fair means of distributing the property to the beneficiaries. This may take the form of equal division (if appropriate) or some other method of distribution. | |

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Knapton [1941] 2 All ER 573 |

| The testatrix in her will provided for a number of houses to be distributed ‘one each to my nephews and nieces and one to Nellie Hird one to Florence Knapton one to my sister one to my brother’. The will did not contain a method of distribution. The court decided that the beneficiaries had the right to choose a house in the order in which they were listed in the will and in the event of a failure to agree then the allocation would be by drawing lots. | |

JUDGMENT

| ‘The clear intention of the testatrix is that each of the nephews and nieces should have a house. I think that it is equally clear that each of those nephews and nieces is to have a choice in priority to those devisees named later in the will. Accordingly, I construe this as a devise of: A house to each of my nephews and nieces, a house to Nellie Hird, and my nephews and nieces are to have a choice before Nellie Hird. How are they to choose? If they cannot agree, then, by the principle of the civil law, the choice must be determined by lot.’ |

| Simonds J |

3.3.3 Effect of uncertainty of subject-matter

The consequences of uncertainty of subject-matter vary with the nature of the subject-matter. If the trust property is uncertain, then no express trust could have been intended by the settlor, for no trust may attach on property that has not been identified. The effect is that the transferee of the property retains the property beneficially. No resulting trust arises.

If, on the other hand, the trust property is certain but the beneficial interest is uncertain, the intended express trust will fail but a resulting trust will arise in favour of the transferor. In these circumstances, although the intention to create a trust is clear, the scope or division of the trust property is incapable of being resolved and thus a resulting trust will arise, see Boyce v Boyce (above).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>