The Statutory Scheme

THE STATUTORY SCHEME

(1) Introduction

4.01 This chapter examines the statutory adjudication scheme contained in Part 1 of the Scheme for Construction Contracts (‘the Scheme’).1 Originally created to work together with the Housing Grants Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (‘the 1996 Act’) the Scheme has been amended to accommodate the changes introduced by the Local Democracy, Economic Reform and Construction Act 2009 (‘the 2009 Act’). The amended Scheme came into force in England on 1st October 2011.2 For the purpose of this chapter they will be referred to as the Scheme or the amended Scheme.

4.02 The Scheme contains provisions that give effect to the mandatory requirements in s. 108 of the 1996 and 2009 Acts, plus additional provisions which will govern any adjudication conducted under the Scheme.

When Does the Scheme Apply?

4.03 The Scheme will apply if it is so stated in the contract, if the parties have chosen it to be the applicable adjudication procedure, or if there is no agreed adjudication procedure in a construction contract.3 In the latter situation the terms of the Scheme have effect as implied terms of the contract.4

4.04 If an adjudication scheme included in a construction contract (or otherwise agreed) conflicts with or fails to comply with the minimum requirements contained in s. 108(1)–(4) then according to s. 108(5) that entire contract adjudication scheme is replaced with the statutory Scheme for Construction Contracts: David McLean Housing Contractors Ltd v Swansea Housing Association Ltd (2001),5 Aveat Heating Ltd v Jerram Falkus Construction Limited (2007).6 This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 3 at 3.98–3.99.

4.05 Where a contract has an adjudication procedure that complies with the Act the juridical nature of adjudication is contractual rather than statutory. This means that, assuming the contractual provisions are in accordance with the Act, it is those provisions which have to be construed and operated by the parties and must be at the forefront of the consideration of the parties’respective rights and liabilities in an adjudication: Cubitt Building Interiors Ltd v Fleetglade Ltd (2006).7 This is important as parties sometimes focus on the provisions of the Act instead of their own procedure which may contain more onerous terms than the Act itself.

Changes Introduced by the 2009 Act

4.06 The main changes made to the Scheme are as follows:

• To give effect to the new s. 108(3A) the amended Scheme now includes at paragraph 22A an express power to correct the decision to remove clerical or typographical errors. This is discussed below at 4.109–4.117.

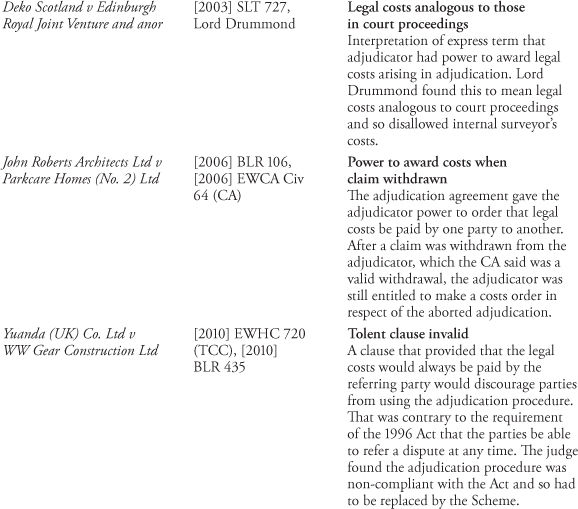

• The new s. 108A renders ineffective any provision about the allocation of ‘costs relating to the adjudication’ unless it is made in writing, contained in the construction contract, and confers power on the adjudicator to allocate his fees and expenses between the parties or, alternatively, it is an agreement made in writing after the notice of adjudication has been given. The Scheme paragraphs 9(4), 11(1) and 25, which concern the adjudicator’s fees, have all been amended and the following words introduced: ‘Subject to any contractual provision pursuant to section 108A(2) of the Act, the adjudicator may determine how the payment is to be apportioned and the parties are jointly and severally liable for any sum which remains outstanding following the making of any such determination.’ These changes are discussed at 4.125–4.147 below.

• The power to order peremptory relief at paragraph 23(1) has been deleted, as has the express application to the Scheme of s. 42 of the Arbitration Act 1996 in paragraph 24.

• There are relatively minor drafting changes made to paragraphs 1(1), 7(3), 15(b), 19(1), 20(b), and 21.

4.07 It would appear from the language of the new s. 108A that it is intended to render ineffective only an offending clause as opposed to the whole adjudication procedure. This is consistent with s. 108(5) where by the Scheme is imported when the construction contract does not comply with s. 108(1)–(4) of the Act – compliance with the new s. 108A is not included within that mechanism. If this is right then standard-form procedures will not have to be amended to give effect to the new s. 108A, but any offending term concerning costs will simply be struck out.

4.08 The same may not be true for the new s. 108(3A). Many contract adjudication procedures do contain such a power to correct slips but those that do not will need to be amended to include this new power or face the risk that this omission will cause the entire adjudication procedure being struck down altogether pursuant to s. 108(5) and replaced by the Scheme.

(2)Starting the Adjudication: Scheme Paragraph 1

The Notice of Adjudication

4.09 The adjudication process is commenced by a notice of intention to refer a dispute to adjudication.8 This document is most commonly referred to as the notice of adjudication, as it is in the Scheme, although terminology in individual contracts differs.

4.10 The Act does not contain any requirements for the form or content of the notice of adjudication. However the Scheme and most standard-form adjudication procedures require the notice to be in writing and some specify what information ought to be contained in it.

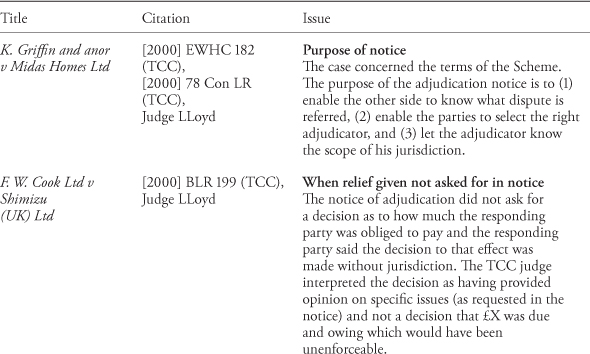

4.11 The Scheme requires the notice shall give a brief description of the dispute and of the parties involved, the details of when and where the dispute has arisen, the nature of the redress which is sought, and the names and addresses of the parties.9 The various standard-form procedures differ in approach and care must be taken to ensure that the notice of adjudication conforms to the stipulations of the relevant adjudication procedure.

4.12 The notice needs to be drafted so as to avoid some common problems that can arise. In particular:

(1) If the contract adjudication scheme mirrors s. 108 and permits the reference of a single dispute then the notice of adjudication should be drafted in such a way as to define the issues between the parties as a single dispute. It may be possible to raise a jurisdictional challenge against a notice of adjudication that refers to several disputes if only a single dispute is permitted. It is usually possible to avoid this outcome by drafting the dispute in wide terms.10 However there seems to be no reason why a contract could not go further than s. 108 and permit more than one dispute to be referred at a time. The Scheme 8(1) permits the adjudicator to consider more than one dispute as long as the parties consent.

(2) If the notice of adjudication describes the dispute in narrow specific terms there is a risk that changes in the dispute, which commonly occur as arguments develop, will be subject to the jurisdictional challenge that they fall outside the definition in the notice. The notice of adjudication ought to describe the dispute in wide terms to protect against such arguments.11

(3) The notice of adjudication ought to comply with the requirements of the relevant adjudication scheme. Failure to comply with the formalities required may run the risk of an argument that the notice of adjudication is invalid. To avoid jurisdictional challenges based on inadequacies of the notice it ought to be drafted to contain (i) a brief description of the contract, (ii) a brief description of the issues, framed widely as one dispute, and (iii) the nature and extent of the remedy requested from the adjudicator.

(4) Where a claim is made for a sum of money the notice of adjudication should ask in the alternative for ‘such other sum as the adjudicator thinks fit’. This gives the adjudicator jurisdiction to make a decision for a lesser sum if necessary. Without such a request the adjudicator’s jurisdiction will most likely be restricted to finding wholly in favour of the referring party’s case or not at all.

4.13 The notice of adjudication plays an important role in defining the scope of the dispute over which the adjudicator has jurisdiction. The adjudicator is appointed to decide the dispute set out in the notice of adjudication. It is then only that the dispute should be referred to him. Unless there is a later agreement to widen the dispute contained in the notice of adjudication, or this is permitted by the terms of the adjudication procedure, the scope of the dispute for adjudication is determined by that set out in the notice of adjudication.12

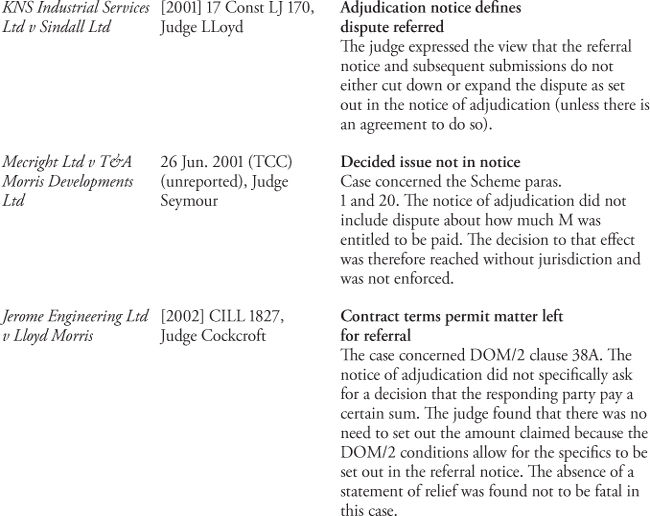

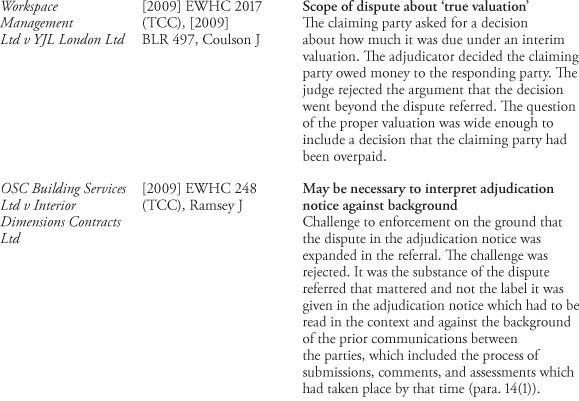

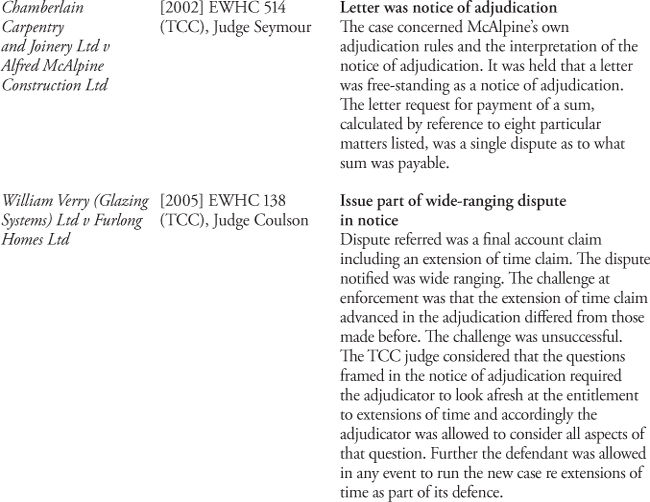

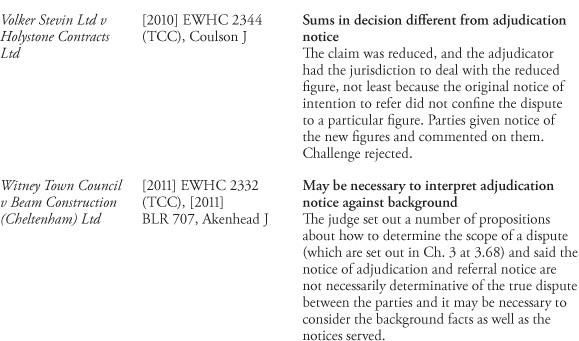

4.14 Hence a decision by the adjudicator on matters outside those in the notice of adjudication will exceed his jurisdiction unless the parties confer additional jurisdiction on him, one party waives the lack of jurisdiction and allows him to deal with the widened dispute, or there is an express term in the adjudication procedure which permits the dispute to be altered in the relevant way. The cases in Table 4.1 concerned arguments that the decision reached by the adjudicator went outside what was stated in the notice of adjudication. In some cases the court was able to construe the notice as being wide enough to cover the decision reached. The court will sometimes be willing to interpret the scope of the dispute contained in the notice of adjudication by reference to the prior communications between the parties on the subject, as in OSC Building Services Ltd v Interior Dimensions Contracts Ltd (2009)13 where Ramsey J said it was the substance of the dispute that mattered and not the label given to it in the notice of adjudication.14 However where the decision clearly goes beyond the scope of the notice it will be unenforceable for want of jurisdiction.

4.15 As discussed in more detail at 3.59 and 9.06, the scope of the dispute referred will include any legitimate defence available to the responding party, even though not expressly cited in the notice of adjudication. However, this only applies to defences that are legally available. So when it is argued before the adjudicator that a withholding notice would have been required but had not been served, the adjudicator is entitled to decide that the cross-claim is excluded as a consequence: Letchworth Roofing Company v Sterling (2009).15

Key Case: Notice of Adjudication

Table 4.1 Table of Cases: Notice of Adjudication

A Single Dispute

4.18 The first paragraph of the Scheme permits a party to refer a dispute, expressed in the singular, to adjudication. The meaning of ‘dispute’ has been considered in numerous cases which are discussed fully in Chapter 3.16 That line of authority applies equally to both statutory and contractual adjudications. The concept of a single dispute is also discussed at 3.49–3.52.

4.19 Like s. 108(1), the Scheme also refers to a dispute ‘arising under the contract’. The scope of this phrase has been considered at 3.10–3.26. A wider contractual adjudication clause that permits disputes arising under and ‘in connection’ with the contract will still be valid. Such a provision will permit a wider class of disputes to be referred, as discussed at 3.12.

4.20 Whilst paragraph 1 of the Scheme permits a single dispute to be referred there seems to be no reason why a contract could not go further than this and expressly permit more than one dispute to be referred at a time.

Additional Disputes and Additional Parties

4.21 Paragraph 8(1) of the Scheme permits the adjudicator to consider more than one dispute as long as the parties consent. It also permits related disputes under different contracts between other parties to be adjudicated upon at the same time. Consent is essential for there to be consolidation of these other claims and it cannot be achieved by the back door without consent: Pring & St Hill Ltd v c. J Hafner t/« Southern Erectors (2002).17 In Pring the party found liable in adjudication 1 requested appointment of the same adjudicator in adjudications 2 and 3 in which it sought to pass on its liability to its own subcontractors. The TCC judge held that where the adjudicator was to decide related disputes under the same contract in parallel adjudications, consent had to be obtained. The adjudicator was found to have erred in going ahead without the consent of one party who objected to his appointment.

4.22 Some standard procedures also permit joinder of other parties, subject always to consent, for instance:

• The ICE 1997 Adjudication Procedure (paragraph 5.7) says that other parties can be joined to the adjudication subject to the agreement of the adjudicator and all the parties.

• The NEC 3 adjudication procedure Option W2 provides (at paragraph W2.3(3)) where the matter in dispute under the main contract is also disputed between the contractor and a subcontractor, then, subject to the consent of the subcontractor, the contractor may refer the connected dispute to the same adjudicator to be decided at the same time as the main contract referral.

• The CIC Model Adjudication Procedure (4th edn) at paragraph 23 allows additional parties to be joined into the adjudication, subject to the consent of the parties and the adjudicator.

Notice at Any Time

4.23 The drafting of the original Scheme has been amended to introduce the words ‘at any time’ into paragraph 1. Accordingly paragraph 1 of the amended Scheme now reads that ‘Any party to a construction contract may give written notice (the ‘notice of adjudication’) at any time of his intention to refer any dispute arising under the contract to adjudication’. This change was to tidy up the drafting of the existing Scheme to make absolutely clear that notice could be given at any time as required by s. 108(2)(a) of the 1996 Act. For a fuller discussion of the meaning of the phrase ‘at any time’ see 3.73–3.82 above. In summary ‘at any time’ means what it says and there is no time restriction on the right to refer a dispute to adjudication. It is, therefore, permissible to refer a dispute arising under the contract to adjudication after the work has been completed or after the contract has been repudiated or terminated.

(3) Appointment and Referral within Seven Days: Scheme Paragraphs 2-11

The Adjudicator’s Appointment: Scheme Paragraphs 2-6

4.24 Once notice of an intention to adjudicate has been given the referring party needs to secure the appointment of an adjudicator and refer the dispute to him or her. The contract procedure should provide a timetable with the object of securing both the appointment and the referral within seven days of the notice of adjudicatiori.18 The seven-day period begins immediately after the date the notice of intention to refer is given.19

4.25 The Act contains no requirements as to how the adjudicator shall be appointed, hence this is left up to the parties. The appointments procedures contained at paragraphs 2-6 of the Scheme are subject to the overriding right of the parties to agree who shall act as adjudicator in relation to a dispute; this is expressed in the introductory words of paragraph 2(1): ‘Following the giving of notice of adjudication and subject to any agreement between the parties to the dispute as to who shall act as adjudicator.’ If no agreement has been reached the Scheme provides that:

(1) The referring party must request an individual named in the contract to act as adjudicator (Scheme paragraph 2(1)(a)).

(2) If there is no named individual or he/she is unavailable then the referring party shall make an application to any nominating body named in the contract (Scheme paragraph 2(1)(b)).

(3) If neither option applies then the referring party shall ask an adjudicator nominating body to select an adjudicator (Scheme paragraph 2(1)(c)).

4.26 The Scheme contains various measures designed to ensure that the adjudicator’s appointment is made in time to enable the dispute to be referred within seven days. Where a person is requested to act pursuant to paragraph 2(1) he or she must respond within two days of receiving the request saying whether he or she is willing or able to act (Scheme paragraphs 2(2) and 5(3)). If the answer is no, or if no answer is received in the time stipulated, then the referring party may start again and the alternative adjudicator must again respond within two days (Scheme paragraph 6).

4.27 The requisite response period is five days where it is an adjudication nominating body which is asked to select an adjudicator (Scheme paragraph 5(1)). If the first-choice nominating body fails to appoint an adjudicator then the referring party may agree with the other party to the dispute to request a specified person to act or may request any other adjudicating body to appoint an adjudicator (Scheme paragraph 5(2)). However, as five days will have already passed, this time there are only two days allowed for the person selected to indicate whether he or she is willing to act (Scheme paragraph 5(3)).

4.28 It is a strict requirement of the Scheme that the request for appointment of an adjudicator is not made until after the notice of adjudication is served. A failure to comply with this requirement may render the adjudicator’s appointment invalid and the decision as being unenforceable: IDE Contracting Ltd v R. G. Carter Cambridge Ltd (2004),20 Vision Homes Ltd v Lancsville Construction Ltd (2009).21 However, bespoke adjudication schemes need not adopt this approach and it is not necessary for such a procedure to require the first step be the service of the notice of adjudication. Nor is it necessary for the options to be sequential and a series of options that can be selected by choice is valid; Palmac Contracting Ltd v Park Lane Estates (2005),22 Dalkia Energy & Technical Services Ltd v The Bell Group Ltd (2009).23

4.29 In principle an adjudicator appointed in contravention of the agreed appointment procedures will not have jurisdiction to decide the dispute. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 9 at 9.27–9.28 and Table 9.3.

4.30 If the appointment procedure in the contract is unworkable the Scheme will apply: David McClean Housing Ltd v Swansea Housing Association (2001),24 AMEC Capital Projects Ltd v Whitefriars City Estates Ltd (2004).25 If the construction contract contains no provisions at all for the appointment of an adjudicator, the Scheme will apply: Bovis Lend Lease v Cofely Engineering Services (2009).26

4.31 Objecting to the appointment of a certain adjudicator will not invalidate his appointment, as long as the relevant appointment procedures are followed. This point is made expressly in the Scheme at paragraph 10.

4.32 Whilst the Scheme does not provide a pro forma agreement to be entered into between the parties and the adjudicator, many standard-form adjudication procedures do provide an adjudicator’s agreement form. It is also common for adjudicators themselves to require the parties to agree to their own terms and conditions.

4.33 The Scheme does not say that the adjudicator shall be independent but paragraph 4 requires that a person requested or selected to act as an adjudicator shall not be an employee of any party to the dispute and shall declare ‘any interest, financial or otherwise, in any matter relating to the dispute’. This means that the appointment of an employee of either party will be an invalid appointment. Such an adjudicator will have no jurisdiction to decide the matter and his decision will not be enforceable.27 It is less clear what remedy is available to a party if the adjudicator validly selected and appointed by a nominating body declares an interest in the dispute that is objectionable to one party but he will not resign. It is submitted that it will depend on whether the facts give rise to an argument of apparent bias on the part of the adjudicator (as discussed in Chapter 11).

4.34 In Makers (UK) Ltd v London Borough of Camden (2008)28 one party suggested to RIBA to appoint a named adjudicator (because he was qualified both as an architect and as a lawyer) and RIBA acceded to that requested. An enforcement challenge based on bias was rejected and the court found there was no duty to consult the other party where suggestions about nomination were made. In Fileturn Ltd v Royal Garden Hotel Ltd (2010)29 the TCC judge rejected a similar allegation of bias and in so doing said there was no objection in principle to the fact that the adjudicator was well known to one or both of the parties.

4.35 The fact that an adjudicator has previously acted as dispute resolver in proceedings involving one of the parties is not of itself sufficient grounds to allege apparent bias or a lack of impartiality: Andrew Wallace Ltd v Jeff Noon (2008).30 In that case the adjudicator had been a mediator of an unrelated dispute with AWL only two days before being appointed as adjudicator by RIBA. The problem partly arose because when RIBA asked if the adjudicator had an existing relationship with either of the parties, the adjudicator said no. Whilst it could be said that the bias accusation might have been avoided had he made the disclosure before being appointed, the editors of the Building Law Reports have noted the Court of Appeal guidance in Taylor v Lawrence31 that ‘judges should be circumspect about declaring the existence of a relationship where there is no real possibility of it being regarded by a fair-minded and informed observer as raising the possibility of bias’.32 Ultimately, the TCC judge in Jeff Noon found the allegation of bias unsubstantiated and was led to this conclusion by the fact that the adjudicator (a) had no personal knowledge of the parties, (b) was a professionally qualified arbitrator, (c) was appointed by RIBA as opposed to being a party appointee, and (d) had no current relationship with either party.

4.36 Allegations of bias on the part of the adjudicator are considered in more detail in Chapter 11.

The Referral Notice: Scheme Paragraph 7

4.37 Once the adjudicator is appointed the dispute must be referred to him. This is done by the service of a statement of case usually called the referral notice. Paragraph 7(1) of the Scheme makes it clear that it is by sending the referral notice to the adjudicator that the dispute is actually referred to him or her (as required by s. 108(2)(b) of the Act).

4.38 The date of ‘the referral’ itself is significant because it starts the clock ticking for the adjudicator to reach a decision within 28 days of that date: s. 108(2)(c).33 For this purpose the ‘date of the referral’ is usually when he receives the referral notice itself: Aveat Heating Ltd v Jerram Falkus Construction Ltd (2007).34 Indeed many of the standard-form procedures define the date of ‘the referral’ as being the date it is received. The amended Scheme now contains two sets of amendments which clarify this:

• The following words are inserted into paragraph 7(3): ‘Upon receipt of the referral notice the adjudicator must inform every party to the dispute of the date it was received.’

• Paragraph 19 has been amended as follows:

19. — (1) The adjudicator shall reach his decision not later than —

(a) twenty eight days after the date receipt of the referral notice mentioned in paragraph 7(1), or

(b) forty two days after the date receipt of the referral notice if the referring party so consents, or

(c) such period exceeding twenty eight days after receipt of the referral notice as the parries to the dispute may, after the giving of that notice, agree.

4.39 Unless otherwise stated in his appointment, an adjudicator has no power to proceed or give directions until he has received the referral notice: Lanes Group Plc v Galliford Try Infrastructure Ltd (2011).35

4.40 The Act does not stipulate any particular form or content for the referral notice and this is left to the applicable adjudication procedure. The Scheme simply says the referral notice shall be accompanied by copies of the contract and documents relied on. In contrast many of the standard adjudication procedures are more prescriptive, expressly requiring the referring party to provide a full explanation of the claim and the supporting information. The referring party ought to ensure the referral does not expand or materially change the dispute set out in the notice of adjudication (as discussed above at 4.14) to avoid jurisdictional challenges being raised by the responding party. Similarly the referral notice should comply with the formal requirements of the Scheme or other applicable adjudication rules although not every breach of the rules will result in there being a valid jurisdiction challenge: PT Building Services Ltd v ROK Euro Build Ltd (2008).36 In that case the contract was provided a day after the referral notice contrary to the Scheme requirement that it be served with the referral. The TCC judge rejected this as a jurisdiction challenge.

Within Seven Days

4.41 After the valid appointment of the adjudicator the referring party shall, not later than seven days from the date of the notice of adjudication, refer the dispute in writing (the ‘referral notice’) to the adjudicator (Scheme paragraph 7(1)). This gives effect to s. 108(2) (b) of the Act.

4.42 It has been decided in several cases that the seven-day time limit in paragraph 7(1) of the Scheme is mandatory: Hart Investments Ltd v Fidler and anor (2006).37 In Hart the referral notice served more than seven days after the notice of adjudication was found to be invalid and the adjudicator’s decision was not enforced for want of jurisdiction.38 For consideration of the cases in which enforcement of adjudication decisions have been challenged on the ground that the referral was out of time, see Chapter 9 at 9.29–9.34.

4.43 An adjudicator appointed pursuant to the Scheme does not have power to extend time for service of the referral notice before it arrives for two reasons: first, the adjudicator is not seized of the adjudication until the referral notice is provided and has no power until then; secondly, as decided in Hart, the only express power to extend time is in paragraph 13 of the Scheme and that provision does not permit the adjudicator to ignore the express time limits unless the extension is consented to.

Resignation or Revocation of Appointment: Scheme Paragraphs 9 and 11

4.44 The Scheme at paragraph 9(1) stipulates that an adjudicator may resign at any time on giving written notice. It is common practice for a responding party making a jurisdiction objection to invite the adjudicator to resign. If the adjudicator comes to the conclusion that the jurisdiction objection is a good one then he ought to resign. However 9(1) is not limited to those situations and the adjudicator may resign for any reason at all.

4.45 Equally the parties may at any time agree to revoke the appointment of an adjudicator: Scheme paragraph 11.

4.46 Pursuant to paragraph 9(2), the adjudicator must resign if the dispute he is asked to decide is the same (or substantially the same) as one already referred to an adjudication in which a decision has been taken. This is because if the dispute has already been decided, and is binding until finally determined, there is no dispute that is capable of being referred to the second adjudicator, with the result that the second adjudicator will have no jurisdiction to decide the second dispute: Sherwood Casson Ltd v MacKenzie (2000).39

4.47 Whether one dispute is substantially the same as another dispute is a question of fact and degree: Quietfield Ltd v Vascroft Construction Ltd (2006).40

4.48 Standard-form contract adjudication schemes do not always mention an express obligation of an adjudicator to resign in these circumstances. However, whether or not the contract has a term equivalent to paragraph 9(2) of the Scheme, the same jurisdictional question will arise: HG Construction Ltd v Ashwell Homes (East Anglia) (2007).41

4.49 Cases in which the court has been asked not to enforce an adjudicator’s decision because it overlapped with a previous adjudicator’s decision are considered in Chapter 6 at 6.64–6.69.

4.50 Paragraph 9(2) of the Scheme does not operate until after a decision has been reached by the first adjudicator. Accordingly if there are two competing adjudications occurring at the same time concerning the same dispute, paragraph 9(2) does not mean that one of the adjudicators must resign: Vision Homes Ltd v Lancsville Construction Ltd.42

4.51 If the adjudicator considers the dispute is too complex or substantial for him to deal with fairly within the time available, he may ask for further time and if it is refused he ought to resign: Amec Group Ltd v Thames water Utilities Ltd (2010).43 There have been various attempts to challenge enforcement of an adjudicator’s decision on the grounds that the dispute was too complex for adjudication. Those cases are considered in Chapter 10 at 10.17–10.18.

4.52 Whether the adjudicator is entitled to be paid fees following resignation or revocation of the appointment is considered in 4.125–4.134 below.

4.53 Where an adjudicator has resigned pursuant to Scheme paragraph 9(1) the referring party may serve a fresh notice and start again (paragraph 9 (3)). The parties shall supply the replacement adjudicator with documents provided to the first adjudicator but only ‘if requested by the new adjudicator and insofar as it is reasonably practicable’. As a matter of principle however, paragraph 9(3) does suggest that a party should not be prevented from starting a fresh adjudication where the first adjudication has not resulted in a binding decision. A similar point is made in paragraph 19(2) of the Scheme which says that where an adjudicator fails, for any reason, to reach his decision in accordance with paragraph 19(1) (i.e. within the time limits stated) any of the parties to the dispute may serve a fresh notice and request an adjudicator to act. The question of whether a party may withdraw a dispute or part of a dispute from an adjudicator and start again has been debated in a number of cases that are discussed in Chapter 9 at 9.49 onwards.

(4) The Powers of the Adjudicator: Scheme Paragraphs 12-18

4.54 As far as the powers of the adjudicator are concerned, the only obligatory provisions for a contract adjudication scheme are those at s. 108(2)(e) and (f) of the Act which stipulate that the contract must: (e) impose on a the adjudicator a duty to act impartially, and (f) enable the adjudicator to take the initiative in ascertaining the facts and the law. The Scheme goes beyond the minimum requirements of the Act and sets out in detail what the adjudicator may do.

Duty to Act Impartially: Scheme Paragraph 12

4.55 To act impartially is to act without bias towards any party. Arguably the adjudicator’s duty to act impartially is implicit in all adjudication procedures as an adjudicator is obliged to conduct the adjudication fairly. The failure to act impartially is a ground for challenging the validity of an adjudicator’s decision. This topic is dealt with in detail in Chapter 11 on the subject of bias. Neither the 1996 Act nor the Scheme expressly state that the adjudicator must be independent although some contractual procedures do say this. Ultimately, any perceived lack of independence of the adjudicator will be a factor in the consideration of whether there is a real danger that the adjudicator may appear to be biased.44

Power to Take Initiative to Ascertain Facts and Law: Scheme Paragraph 13

4.56 In contrast to the imposition of the positive duty in s. 108(2)(e), the 1996 Act only requires that the adjudicator is enabled to ascertain the facts and the law. In other words he must be given the power to do so, but he is not obliged to use it. Consequently the Scheme at paragraph 13 says that the adjudicator may take the initiative. An adjudicator is empowered therefore to conduct the adjudication in an inquisitorial fashion. Alternatively he may prefer to allow the parties or their representatives to take responsibility for this. Equivalent powers are bestowed on adjudicators by most standard contractual procedures.

4.57 Paragraph 13 of the Scheme sets out the various ways in which a Scheme adjudicator may take the initiative:

13. The adjudicator may take the initiative in ascertaining the facts and the law necessary to determine the dispute, and shall decide on the procedure to be followed in the adjudication. In particular he may –

(a) request any party to the contract to supply him with such documents as he may reasonably require including, if he so directs, any written statement from any party to the contract supporting or supplementing the referral notice and any other documents given under paragraph 7(2),

(b) decide the language or languages to be used in the adjudication and whether a translation of any document is to be provided and if so by whom,

(c) meet and question any of the parties to the contract and their representatives,

(d) subject to obtaining any necessary consent from a third party or parties, make such site visits and inspections as he considers appropriate, whether accompanied by the parties or not,

(e) subject to obtaining any necessary consent from a third party or parties, carry out any tests or experiments,

(f) obtain and consider such representations and submissions as he requires, and, provided he has notified the parties of his intention, appoint experts, assessors or legal advisers,

(g) give directions as to the timetable for the adjudication, any deadlines, or limits as to the length of written documents or oral representations to be complied with, and

(h) issue other directions relating to the conduct of the adjudication.

4.58 In performing these functions the adjudicator must always be careful to act fairly and impartially and must not introduce matters which are outside the scope of the adjudication and thus outside his jurisdiction. If he invites a party to alter or increase the scope of the dispute referred he may ultimately be judged to have reached a decision outside his jurisdiction: McAlpine PPS Pipeline Systems Joint Venture v Transco plc (2004).45

4.59 In Volker Stevin Ltd v Holystone Contracts Ltd (2010)46 the enforcement of a decision was challenged on a number of grounds, one of which was that the adjudicator had exceeded his jurisdiction by asking for more material after the deadline he had set. The TCC judge found that the adjudicator had been entitled to make enquiries to obtain further information and to take account of responses. If the adjudicator needed further information in order to allow him to answer questions properly, he was entitled, indeed obliged, to ask for it. An adjudicator should not stand mutely by, hoping that one side or the other gives him the information that he wants; if he considers that he lacks vital information, he must take the initiative and ask for it directly. Further, in Volker the adjudicator had ensured that the process was fair by showing the other side the new material and giving it the opportunity to comment. The challenge was rejected.

4.60 Jurisdictional issues that may arise from the approach taken by the adjudicator are discussed more fully in Chapter 9.

Using Own Knowledge or Experience

4.61 The Scheme does not expressly say that the adjudicator may use his own experience or expertise, although paragraph 13(f) does enable him to appoint experts, assessors or legal advisers to help him as long as he has notified the parties of his intention to do so.

4.62 Other standard-form procedures expressly provide that an adjudicator may act as an expert himself and/or may use his own knowledge and experience: the GC Works contract scheme says the adjudicator shall act as an expert adjudicator (clause 59(6)); the CIC Model Adjudication Procedure (4th edn) states he may use his own knowledge and experience (clause 3); JCT clause 41A.5.5.1 says he may use his own experience or knowledge; the ICE 1997 Adjudication Procedure says that the adjudication is ‘neither expert determination nor arbitration but the adjudicator may rely on his own expert knowledge and experience’ (General Principles).

4.63 It is submitted that, in principle, the Scheme would allow an adjudicator to use his own knowledge as long as he complies with paragraph 17 which requires him to make available to the parties any information to be taken into account when making his decision. He should also provide the parties with a reasonable opportunity to make submissions on that material, as discussed in more detail in Chapter 10. If the adjudicator fails to give the parties an opportunity to consider and respond to material obtained by him and relied upon in the decision it may result in a breach of natural justice that renders the decision unenforceable.47 Equally, the adjudicator must disclose advice provided by third parties and invite the parties to make submissions on it.48 The adjudicator is not permitted to rely on his own knowledge or experience to reformulate the case and decide it on a basis different from the dispute referred. In Herbosh-Kiere Marine Contractors Ltd v Dover Harbour Board (2012)49 the adjudicator’s decision relied on a formula that had neither been part of the dispute in the referral nor the response. The court found that this was both a breach of natural justice, as the parties were not given a chance to consider it, and was a decision made without jurisdiction given that it was outside the dispute referred. Effectively the adjudicator had answered the wrong question. In different circumstances, it may be valid to decide on a basis that neither party argued where the adjudicator is answering a broad question posed by the dispute as referred, as was the case in Multiplex Constructions (UK) Ltd v Mott MacDonald Ltd (2007).50 Alternatively, a court may dismiss a complaint made about an argument raised for the first time in the decision if it was not a central point in the decision nor was the basis on which the decision was made.51

Power to Decide the Procedure

4.64 Save for the time limit for the adjudicator to reach his decision, nothing is said in the 1996 Act about how the adjudication shall be conducted after the referral notice is provided. This is left for the specific adjudication procedure in the contract or the Scheme, whichever is applicable. Thus individual contract schemes are free to predetermine what procedures and timetables will be applicable.

4.65 Pursuant to the Scheme there is no predetermined procedure and the adjudicator must decide the procedure to be followed himself (paragraph 13). This means he may make directions as to what submissions shall be provided or may direct that he will hear the arguments and obtain evidence by any of the methods set out in paragraph 13(a)-(g). He is not limited by the specific options of paragraph 13 for he has a broad power to issue other directions relating to the conduct of the adjudication as he sees fit (paragraph 13(h)). He has a complete discretion as to the timetable (subject to meeting any time limit for reaching his decision) and may impose deadlines for the provision of submissions and may even require their length to be restricted (paragraph 13 (g)).

4.66 However, the adjudicator’s powers are always subject to his overarching duty to act fairly and impartially and accordingly any timetable imposed must be fair to both parties. In NAP Anglia Ltd v Sun-Land Development Co Ltd (2011)52 the court rejected an allegation that the submissions timetable ordered by the adjudicator was unfair on the respondent or was a breach of natural justice. The procedure may also be subject to any compulsory deadlines contained in the adjudication agreement or any applicable adjudication rules. As outlined at 4.41–4.43 and 4.97–4.104 of this chapter and more fully in Chapter 9 at 9.29 and following, the deadlines in the Scheme for the provision of the referral and making the decision are obligatory. The time for referral may not be extended and the adjudicator may not extend time for reaching his decision without consent of one or both parties.

4.67 The adjudication procedure may, as discussed below, include a deadline for the service of a defence. The question has arisen whether the adjudicator may extend the time for the defence and the effect of a failure to do so. This is discussed below and in Chapter 10 at 10.36–10.41.

Defence and Counterclaims

Form and Timing

4.68 The 1996 Act says nothing about the provision of a defence and so this is left to the individual adjudication procedures. The Scheme does not specifically provide that the respondent shall provide a written defence. It is for the adjudicator to decide the procedure but he is specifically empowered to obtain and consider such representations and submissions as he shall require (paragraph 13(f)), make directions about service of written documents (paragraph 13(g)), or make any other direction relating to the conduct of the adjudication (paragraph 13(h)). Although the respondent usually is required to put its defence in written form, this is a matter for the adjudicator who may prefer to elicit information by other means such as meeting and questioning the parties himself (paragraph 13(c)). This must all be done within the overarching duty to act fairly and impartially.

4.69 Other standard adjudication procedures take a different approach and predetermine that the responding party may submit a written response to the claim within a specified period. It is not uncommon for the responding party to have just seven days from the date of the referral to provide its response.

4.70 These predetermined timescales are not, however, necessarily a final date for the submission of the defence that cannot be extended: CJP Builders Ltd v William Verry Ltd (2008).53 In that case the contract was in the DOM/2 form, of which clause 38A.5.1.2 provides that the respondent may send the adjudicator a response within seven days of the referral. Akenhead J said this was not the latest date a defence could be considered. Furthermore he went on to say that, because the contract provided that the adjudicator shall set his own procedure, the adjudicator had power to extend time and failure to do so was a breach of natural justice in this case.

4.71 The question of what happens if the respondent fails completely to put in a written submission requested by the adjudicator is discussed at 4.75–4.79 below.

Content

4.72 As discussed at 4.13 above every dispute referred to an adjudicator is defined by reference to the notice of adjudication. The dispute cannot be cut down or enlarged by subsequent documents without agreement between the parties. However, whatever dispute is referred, it includes and allows any ground open to the responding party which would amount in law or in fact to a defence of the claim: KNS Industrial Services Limited v. Sindall (2001).54 The responding party is not restricted to (a) arguments that have been aired previously and/or (b) matters mentioned in the notice of adjudication.

4.73 Whilst the general principle is that a defendant can raise defences in adjudication, that does not permit the defendant to run defences or counterclaims that should have been the subject of a withholding notice: Letchworth Roofing Company v Sterling (2009).55 However, as long as the defence in question is not one that needs a withholding notice to have been served, then the general principle is that a respondent is entitled to run any available defence to defend itself against the assertions made in the claim. The relevant cases are discussed in more detail in Chapter 10 at 10.36–10.53.

4.74 An adjudicator has to decide whether or not a withholding notice is required to permit a crossclaim to be raised as a defence and, if so, whether or not there has been a valid notice. If he concludes that no notice was required, or that a notice was required and that there was a valid notice, then he must take the cross-claim into account in arriving at his decision. If he concludes that a notice was required but was not served then he is not entitled to take the cross-claim into account when reaching his conclusion.56 However where an adjudicator wrongly decided that a withholding notice was required and so wrongly excluded a defence of set off, the court decided the error made was one of law. As errors of law are errors made within jurisdiction the decision was nevertheless enforceable; Urang Commercial Ltd v Century Investments Ltd (2011).57

Procedural Breach Does Not Invalidate Decision: Scheme Paragraph 15

4.75 What is the consequence of a party failing to comply with a procedural direction made by the adjudicator, or failing to take part in the adjudication at all? The Scheme at paragraph 15 expressly empowers the adjudicator to continue with the adjudication in any event. He may:

(a) continue the adjudication in the absence of that party or of the document or written statement requested,

(b) draw such inferences from that failure to comply as circumstances may, in the adjudicator’s opinion, be justified, and

(c) make a decision on the basis of the information before him attaching such weight as he thinks fit to any evidence submitted to him outside any period he may have requested or directed.

4.76 This falls short of saying that an adjudicator may ignore information submitted after a directed deadline and subparagraph (c) chimes with paragraph 17 of the Scheme which provides that the adjudicator shall consider any relevant information submitted to him by any of the parties. This mandatory obligation apparently requires the adjudicator to consider late information, as long as it is relevant to the dispute. However it is not always a breach of natural justice for an adjudicator to refuse to consider an argument or evidence particularly when it is submitted very late; see Chapter 10.58

4.77 The effect of paragraph 15 of the Scheme is that a failure of the type identified (namely, where a party fails to comply with any request, direction, or timetable of the adjudicator made in accordance with his powers; fails to produce any document or written statement requested by the adjudicator, or in any other way fails to comply with a requirement under the Scheme provisions relating to the adjudication) will not invalidate the decision of the adjudicator.

4.78 Some contract clauses, such as clause 41A.5.6 of the JCT contract, expressly state that any failure by either party to comply with a requirement of the adjudicator or a term of the adjudication procedure ‘shall not invalidate the decision of the adjudicator’. Such a term however cannot be used to cure failures which rob the adjudicator of jurisdiction–such as the late provision of the referral notice, as discussed in more detail at 9.28 onwards: Palmac Contracting Ltd v Park Lane Estates Ltd (2005).59

4.79 As the decision in CJP Builders Ltd v William Verry Ltd (2008)60 illustrates, a failure to grant an extension of time to serve a defence may be judged to be a breach of natural justice. The same conclusions might not follow if the late information was less crucial. However an adjudicator conducting an adjudication under the Scheme would be unwise to completely ignore relevant information on the sole ground that it was late. Information may however validly be dismissed on the grounds of irrelevance, as discussed at 4.82 below. Chapter 11 considers in more detail the circumstances in which procedural failures may give rise to a breach of natural justice that may affect the enforceability of a decision.

Obligation to Consider any Relevant Information: Scheme Paragraph 17

4.80 The adjudicator shall consider any relevant information submitted to him by any of the parties to the dispute and shall make available to them any information to be taken into account in reaching his decision (Scheme paragraph 17).

4.81 As stated above at 4.72–4.74 a responding party in an adjudication is not limited to points rehearsed before the start of the adjudication: William Verry (Glazing Systems) Ltd v Furlong Homes Ltd (2005).61

4.82 However, if an adjudicator declines to consider evidence which, on his analysis of the facts or the law, is irrelevant, that is neither (a) a breach of the rules of natural justice nor (b) a failure to consider relevant material which undermines his decision on Wednesbury grounds or for breach of paragraph 17 of the Scheme: Carillion Construction Ltd v Devonport Royal Dockyard (2005).62 The extent to which a failure to consider particular evidence may lead to a breach of natural justice is considered in more detail in Chapter 10 at 10.54– 10.62.

Confidentiality: Scheme Paragraph 18

4.83 There is a prohibition imposed on the adjudicator and any party to the dispute by paragraph 18 of the Scheme from disclosing to any other person any information or document provided in connection with the adjudication which the supplying party has indicated is to be treated as confidential, except to the extent that it is necessary for the purposes of, or in connection with, the adjudication.63

(5)The Adjudicator’s Decision: Scheme Paragraphs 19–22

Matters Necessarily Connected with the Dispute

4.84 Paragraph 20 of the Scheme describes the matters which may be dealt with by the adjudicator’s decision. The adjudicator is obliged to decide the matters in dispute and in so doing he is empowered to take into account any other matters which the parties to the dispute agree should be within the scope of the adjudication or which are matters under the contract which he considers are necessarily connected with the dispute. In particular he may:

(a) open up, revise and review any decision taken or any certificate given by any person referred to in the contract unless the contract states that the decision or certificate is final and conclusive,

(b) decide that any of the parties to the dispute is liable to make a payment under the contract (whether in sterling or some other currency) and, subject to s. 111(4) of the Act, when that payment is due and the final date for payment,

(c) having regard to any term of the contract relating to the payment of interest decide the circumstances in which, and the rates at which, and the periods for which simple or compound rates of interest shall be paid.

4.85 In a term similar to paragraph 20 of the Scheme, the TeCSA Adjudication Rules (Version 2.0) empower the adjudicator to decide the matters in dispute and any other matter that the Adjudicator determines should be included ‘in order that the Adjudication may be effective or meaningful’. This is backed by a term that the adjudicator may decide upon his own substantive jurisdiction.64 In Farebrother Building Services Ltd v Frogmore Investments Ltd (2001)65 it was said that this provision was unambiguous and meant that a decision on the scope of an adjudication by the adjudicator could not be challenged in court. However, in Shimizu Europe Ltd V LBJ Fabrications Ltd (2003)66 the TCC judge decided that the TeCSA power to take into consideration other matters was not unlimited. In that case the adjudicator had decided how much ought to have been the amount of an interim payment and said it should be paid ‘without set-off’. Because the contract required a VAT invoice be issued before payment was due the adjudicator said that the invoice should be issued after the adjudication. The judge found that the adjudicator could not by his decision prevent the paying party from serving a withholding notice against that invoice in accordance with the contract terms, and the statement that the sum was payable ‘without set-off’ could only refer to those matters which had been before the adjudicator which he had rejected as the adjudicator could not decide a future right of set-off.

Power to Open Up, Review, and Revise Certificates: Scheme Paragraph 20(a)

4.86 The Scheme gives an adjudicator an express power to open up, revise, and review any decision taken or any certificate given by any person referred to in the contract unless the contract states that the decision or certificate is final and conclusive.

4.87 It has been argued (unsuccessfully) that where the contract reserves the power to open up, review, and revise certificates to the contract administrator then paragraph 20 of the Scheme does not empower an adjudicator to issue a certificate. In Vaultrise Ltd v Paul Cook (2004)67 a dispute arose under a contract in the JCT standard form of contract IFC 98. The court held that an adjudicator can consider whether or not a certificate should have been issued and if a missing certificate was due he could determine the sum. There was no reason why a dispute as whether or not a certificate should be issued, and if so what it should contain, should not be referred to adjudication.

4.88 There was a proposal to include in the 2009 Act a provision making ineffective any contract term that purported to make an interim certificate binding so as to prevent a subsequent review by an adjudicator. This was widely criticized and was dropped.

4.89 A contract term may not prevent the adjudicator from considering a dispute about a certificate or decision made by a certifier. In Banner Holdings Ltd v Colchester Borough Council (2010)68 the TCC judge considered a contract term that said the adjudicator could not vary or overrule the employer’s decision to operate a contractual provision to determine the contract. The judge said the clause was not objectionable because once the decision to determine had been taken it was too late to vary or reverse it. The issue that remained was whether the decision taken was valid and the clause did not restrict the right of the parties to refer that dispute to adjudication. However the judge said that if the clause had restricted the right of the parties to refer the disputes about the validity or conseqences of the determination, it would have been invalid as contrary to s.108 of the Act.69

Power to Award Interest: Scheme Paragraph 20(c)

4.90 There is no requirement pursuant to s. 108 of the Act for the construction contract to confer a power on the adjudicator to award interest. Some contracts include an express right to interest on late payments and some do not. The Scheme says:

20 The adjudicator shall decide the matters in dispute. He may take into account any other matters which the parties to the dispute agree should be within the scope of the adjudication or which are matters under the contract which he considers are necessarily connected with the dispute. In particular he may … (c) having regard to any term of the contract relating to the payment of interest decide the circumstances in which, and the rates at which, and the periods for which simple or compound rates of interest shall be paid.

4.91 This provision contains some ambiguity which has given rise to difficulties. In particular it has been debated whether it creates a free-standing power for the adjudicator to award interest on late payments when the contract contains no express right. In Carillion Construction Ltd v Devonport Royal Dockyard Ltd (2005)70 Jackson J at first instance found that, in adjudications conducted under the Scheme, pursuant to paragraph 20(c) there was a free-standing right to award interest. He found that ‘having regard to any term of the contract relating to the payment of interest’ meant that if there was any such term the adjudicator must have regard to it. In other words, the free-standing right conferred by paragraph 20(c) did not override any express term of the contract. The Court of Appeal disagreed (see Key Case below).

4.92 The award of interest was upheld by the Court of Appeal on different grounds, namely that the respondent had acquiesced in the adjudicator having jurisdiction to consider it. This aspect of the Court of Appeal’s decision is discussed in further detail in Chapter 5 concerning ad hoc submissions.

4.93 It follows from the Court of Appeal’s decision that the adjudicator is empowered to award interest if it is one of the matters in dispute referred to him and (a) there is a contractual right to claim interest or (b) the defendant nevertheless has agreed that the adjudicator shall have the power. It is not however clear what is meant by the words ‘or which are matters under the contract which he considers are necessarily connected with the dispute’ and whether this empowers the adjudicator to consider interest where there is a contract right to it but it has not been included in the referring parties’ claim.

4.94 The Court of Appeal decision in Carillion was limited to whether paragraph 20(c) of the Scheme conferred a free-standing power to award interest. It does not consider the wider question of whether a power to award interest may be derived from other sources. In the absence of a contractual term allowing interest claims to be made a referring party may be able to rely on the Late Payment of Commercial Debts (Interest) Act 1998 or may be able to claim interest as damages for late payment in the manner contemplated in FG Minter v Dawnays.71 It has been suggested that an adjudicator may have an implied power to award interest by analogy with the arbitration precedents.72 This argument was not considered in the judgments in Carillion and remains to be considered by the courts.