The scope and nature of pregnancy-parenting/ workplace conflicts

2

The scope and nature of pregnancy-parenting/ workplace conflicts

No self-respecting small businessmen with a brain in the right place would ever employ a lady of childbearing age.

UKIP MEP Godfrey Bloom cited in The Telegraph (21 July 2004)

Introduction

As chapter 1 suggests, in the twenty-first century we have witnessed unprecedented transformations in how the world of work operates. It is no longer so geographically confined and many labour-intensive industries have declined whilst others, such as the services industry, have flourished. There is a new global economy which operates 24/7 and is more competitive and more regulated than ever before. It is no longer dominated by men, although an increase in the number of women active in the labour market has not meant gender equality at work, and women continue to be discriminated against in many ways.

In the private space of the home, changes have been less radical, and women continue to bear the major responsibilities of caring for the family, although men are indicating more willingness to contribute. Further transformations have occurred in terms of child-rearing expectations, which have become more intense, child-focused and expert-driven, and are often government-led, placing new pressures on parents to meet ever-increasing and competitive standards. The transformations that have occurred in these two interdependent contexts have intensified social and economic gender equalities and it is with these broad contexts and the analytical framework described in chapter 1 in mind that we now turn to consider a disturbing ‘slice’ of modern day work/family relationships, the assessment of which is at the core of this book: the poor treatment of pregnant workers and new parents in the workplace.

In this chapter the scope and the nature of pregnancy and parenting/work-place conflicts are outlined and discussed. How common are such conflicts, and what do they involve? Are there particular cohorts of workers who experience conflicts more than others, or are all parents, mothers and fathers, susceptible to this type of workplace relationship problem? If so, do they all experience conflicts in the same way? Here, the wider picture of pregnancy and parent-related conflicts is uncovered and the implications discussed in order to provide (a) an assessment of what the empirical research drawn upon in this book illuminates and, by implication, what it fails to address (and what remains to be investigated), and (b) an understanding of how widespread, pervasive, damaging and, at present, gendered these types of conflict are. This chapter, and the book in general, draws upon a host of research and literature, but the empirical findings of a Nuffield Foundation funded tribunal study conducted by the author are at its core. Hence, before considering the scope and nature of these conflicts, the methodology involved in this study is outlined.

The tribunal study: methodology

The overall aim of the tribunal study was to investigate the extent, nature and judicial treatment of pregnancy/workplace problems through an analysis of employment tribunal decisions registered in England and Wales. In the UK, when workplace relationships break down, if employees feel they have a claim against their employer they must register their claims at employment tribunals within a certain time frame (three months for unfair dismissal and sex discrimination claims). This is the first stage of the litigation process, and for most it is the last stage, as very few claims advance to Employment Appeals Tribunals (EAT) (see ETS Annual Report and Accounts, available at the Employment Tribunal Services (ETS) website – http://www.ets.gov.uk/index.htm). Employment tribunal decisions are unreported, do not set precedent and are hence often ignored by academics who naturally tend to base their interpretations and doctrinal analysis of the law on those relatively few reported cases that reach the higher courts or the European Court of Justice (ECJ) (see, for example, Boch 1996; Caracciolo Di Torella and Masselot 2001; Conaghan 1998; Cox 1997; Ellis 1991; McGlynn 2001; Wynn 1999). A primary objective of this study was to search beyond the surface of reported case law in the UK. In doing so, it uncovered a mass of hitherto hidden legal activity.

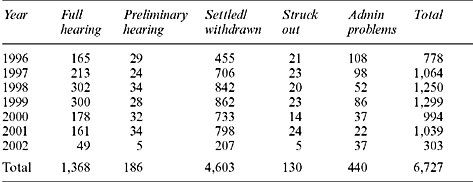

The tribunal study is an investigation of all relevant claims registered in England and Wales between January 1996 and April 2002. Data collation for this study was conducted at the ETS in Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, which houses all of England and Wales’ employment tribunal decisions. It involved two stages and illustrates just how inaccessible this vitally important data is, highlighting concerns regarding lack of transparency and unavailability for public scrutiny. Firstly, the information available on the public ETS register needed to be collated. This register provides information about the number of claims, their date and geographical location, as well as providing the folio numbers for locating the actual tribunal decisions. The register, accessed via one of five available computers at the time, could only be accessed during working hours and was often in high demand. Once accessed the information retrieved could not be downloaded or printed so a written record of the findings had to be taken. Given that the research uncovered several thousand relevant claims, this proved to be very time consuming. The second stage involved locating the decisions in the mass of folio boxes stored at the ETS office (some of which had been bound and archived in a separate building which could only be accessed by ETS staff). Once the decisions were located and the relevant information regarding their outcome was noted, the decisions that had proceeded to a full-merits tribunal hearing were photocopied individually: a process that had to be conducted by a member of the office staff and proved costly at 20p per sheet of A4 paper. That many decisions were incorrectly filed or missing, had been archived, or were in the process of being bound ready for archiving, made this whole process more challenging. It is interesting that during the research 440 decisions were found to be ‘lost’, some of which we know went to a full tribunal hearing, due to‘administrative problems’ of this nature (see Table 2.1).

The study found that 6,727 relevant claims were registered during the period between January 1996 and April 2002. The information available for all the registered claims provides a broad picture of the relevant legal activity and reveals the true scope and outcome of pregnancy-related unfair dismissal litigation in England and Wales. As Table 2.1 demonstrates, most of the claims registered were settled or withdrawn prior to full merit hearings1 but 1,368 did go on to be considered by an employment tribunal panel. Most (over 70 per cent) of these claimants included a claim for sex discrimination, but we know that some claimants who experience pregnancy-related conflicts only register a claim for sex discrimination, not unfair dismissal, and would therefore not be included in this figure. The tribunal study is also, for methodological reasons, restricted to England and Wales. Hence, the figure of actual litigation in the wake of pregnancy-related conflicts is likely to be even higher than this study suggests.

The data contained in the decisions that went to a full-merits tribunal hearing were considered further. These provide a narrative of the complaint,

Table 2.1 Outcome of pregnancy-related unfair dismissal claims registered at employment tribunal in England and Wales between January 1996 and April 2002

|

The scope of pregnancy-parenting/workplace conflicts and the ‘litigation gap’

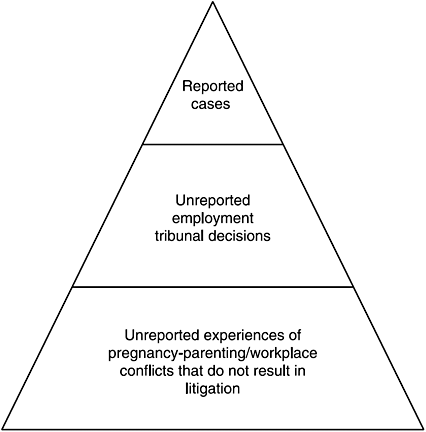

Good family-friendly practices are increasingly viewed as beneficial by employers themselves (Hayward et al. 2007), and research suggests that most employers have a positive attitude, manage pregnancy successfully and appreciate the long-term benefits of good practice (Adams et al. 2005: a qualitative study of women working during pregnancy, where 61 per cent felt their employers were supportive). Indeed, in recent years there have been relatively few pregnancy-related discrimination or unfair dismissal cases in the higher courts of the UK or the ECJ (for further discussion of this legal engagement see chapter 3 and for example, Boch 1996; Caracciolo Di Torella and Masselot 2002; Conaghan 1998; Cox 1997; McGlynn 2001; Wynn 1999), but published cases are only the very tip of the iceberg. As stated above, the tribunal study reveals a mass of unreported legal activity following pregnancy and parenting (or rather, early mothering)/workplace conflicts. On average, over a thousand women annually register claims at employment tribunals in England and Wales. More recently, the ETS has, in its annual report, begun to highlight a separate category of claimant who claim to have suffered a detriment or been dismissed for a reason relating to pregnancy but, again, these figures, like the tribunal study, do not highlight cases where the claimant has brought an action for pregnancy-related sex discrimination claims only and may therefore under-represent the true scope of the litigation. Its figures, nonetheless, support the tribunal study findings and show that in 2004/05 there were 1,345; in 2005/06 there were 1,504; and in 2006/07 there were 1,465 claims of this type registered at tribunals in England and Wales (ETS, 2007:1). If, in terms of pregnancy-parenting/ workplace conflicts as a whole, reported cases are viewed as the tip of the iceberg, the tribunal decisions provide the next layer, hidden beneath the surface.

Although the tribunal study reveals a deeper level of legal conflicts, further research suggests that there is an even larger dimension of pregnancy-parenting/workplace discrimination operating in our labour market. According to research conducted by the National Association of Citizens Advice Bureaux Workers (NACAB), tens of thousands of women are annually dismissed or threatened with dismissal as a result of pregnancy or childbirth (Dunstan 2001). An investigation by the Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC), as part of their general formal investigation of pregnancy discrimination in the UK, suggests that over 30,000 women per year are sacked, made redundant or leave as a result of pregnancy-related discrimination, and that almost half of women who work during pregnancy will be confronted by some form of discrimination (EOC 2004 and 2005). The EOC estimates that annually almost half of the 440,000 pregnant women in Britain will experience some kind of disadvantage at work because they are pregnant or taking maternity leave. Other research suggests that many women are often overlooked for promotion or training when pregnant and are refused paid time off for antenatal classes (O’Grady and Wakefield 1989). The scope of the problem in the UK is depicted in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 The scope of pregnancy-parenting/workplace conflicts in the UK.

Even this picture is, however, incomplete. At a wider level the data provided by the tribunal study and the EOC and NACAB research cannot, because of its parameters, uncover the true extent of all parent/workplace conflicts in the UK. Despite the methodological restrictions stated above, the research is unable to uncover conflicts experienced by those adopting or foster parents, or those with older children. These ought to be defined as parenting/work-place conflicts but are not addressed in these studies. Would-be parents undergoing IVF treatment who experience workplace conflicts are also excluded from these figures. Nor does the picture represent fathers’ experiences of conflict at work caused by parental responsibilities, which may occur if they want to take paternity leave, parental leave or request flexible working of some kind. For the most part it is fair to imagine that ‘parenting/workplace’ conflicts are synonymous with ‘mothering/workplace’ conflicts as it is, at present, working mothers, as opposed to working fathers, who are most likely to take leave, be responsible for childcare and hence experience problems at work as a result. It is however wrong to assume, in the absence of further research, that it is only working mothers-to-be and new mothers who experience discomfort in this regard. Figure 2.1, although a good starting point and representation of what research has revealed so far, may well under-represent the true scope of pregnancy-parenting/workplace conflicts that exist in practice.

Whilst research now provides an initial picture of the potential scope of pregnancy-parenting/workplace conflicts in the UK, further work is needed in order to clarify its more deeply hidden and under-researched elements. In addition, further qualitative investigations of decision making in this context would help us understand the reasons for the lack of litigation, evident in the ‘litigation gap’ – a gap between the numbers experiencing conflict and the numbers actually litigating – revealed by the above research. That such a small number (1,000) of those pregnant women or new mothers experiencing pregnancy-parenting/workplace conflicts at work (30,000) actually pursue an action at an employment tribunal raises a number of important issues. The following chapters of the book seek an explanation, or partial explanation, in the relevant legislation and policies (chapter 3), the application of law at tribunals (chapter 4) and the procedural aspects of the tribunal system (chapter 5), but it may simply be that there is a large capacity amongst these women to tolerate injustice or perhaps they do not perceive what has happened to them as an injurious experience – they do not ‘name’ the experience as something that has caused them harm (Felstiner et al. 1980–81 – see chapter 1). Perhaps these women do not ‘blame’ anyone for what has happened. As Felstiner and colleagues suggest, ‘an injured person must feel wronged and believe that something might be done in response to the injury’ (Felstiner et al. 1980–81:635). Yet, whilst some women may simply wish that they had not been treated badly, others might lack the feeling that anyone in particular is at fault. For example, a woman may feel that being overlooked for promotion or training when pregnant is somehow understandable, as she is about to commence her maternity leave. It may also be at the ‘claiming’ stage that the pregnancy-parenting/workplace conflict experience fails to metamorphose into a litigious dispute. It may be at this point that she feels unwilling to ‘rock the boat’ or unable, perhaps due to lack of detailed knowledge of the relevant law, to ask for a legal remedy.

Of course, all workplace disputes can fail to transform into litigation at these stages, but in the context of pregnancy-parenting conflicts the dominant ideology of motherhood, which would require this potential claimant to give priority to her child (born or unborn) and would naturally include stress aversion, may have a pronounced impact upon her choices. Ultimately, the manifestation of the dominant ideology of motherhood in this context may prevent women from taking legal action because it shifts their emotional, financial and practical priorities. The dominant ideology of fatherhood may also have an impact on decision making in circumstances where he is confronted by workplace conflict, but this ideology may not be as powerful a deterrent from litigation or, alternatively, it may also operate to deter him from claiming, but for different reasons. For example, a father may value his breadwinner role above any childcare responsibilities he has, and therefore lean more strongly towards protecting the former when any potential conflicts arise. Such an attitude may also prevent any conflict arising in the first place. How far these dominant ideologies of motherhood and fatherhood impact upon decision making in the ‘naming, blaming and claiming’ framework is a matter for further investigation, but the impact of such ideologies might be an important factor to consider when attempting to explain the litigation gap in this context.

Furthermore, whilst we should not assume that flaws in the legal regulation are the only or main reason for the litigation gap, nor should we assume that litigation is the only rational choice in this context or, by implication, that those who do not litigate are acting irrationally or are likely to feel a lack of resolution. Indeed, the lack of litigation may indicate a positive rejection of what Hays has called ‘the competitive, self-interested, efficiency-minded and materialistically orientated logic’ of today’s workplaces (Hays 1996:8) in favour of the dominant motherhood ideology whereby ‘working mothers are faced with the power of both logics simultaneously and are forced to make choices between them’ (Hays 1996; 9) (see further chapter 5). In the event of pregnancy-parenting/workplace conflicts, the pull towards ‘motherhood’ identities as opposed to ‘worker’ identities might understandably be stronger. These issues in turn relate to broader issues of preferences and genuine choices (discussed further in chapter 6), but clearly further investigation would help us better understand how, and indeed whether, relevant laws could help these women find a resolution that is appropriate for them when such workplace conflicts arise.