The Rights of the Limited-English-Proficient Accused in the Criminal Courts

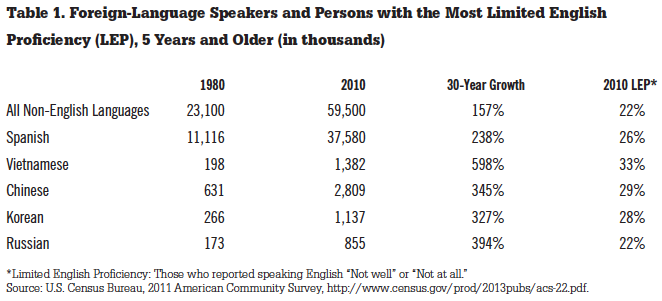

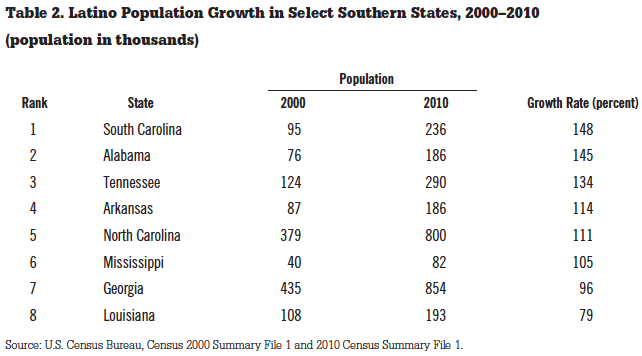

SEVERAL SPANISH-LANGUAGE CONFLICTS ARISE THROUGHOUT THE CRIMINAL justice system. This chapter addresses primarily interpreter problems that the limited-English-proficient (LEP) accused faces in a criminal case. Language issues arise in investigatory and adjudicatory phases of a criminal prosecution, but they are not thoroughly addressed. For example, only a few years ago, Texas’s highest court for criminal matters excluded the LEP convict from a beneficial rehabilitation program based on the absence of Spanish-speaking personnel. The Texas legislature thereafter corrected this injustice by providing that a judge “shall not deny community supervision to a defendant based solely on the defendant’s inability to speak, read, write, hear, or understand English.”1 Similarly, the use of Spanish and slang by informants and suspects in undercover investigations occurs and is often recorded.2 In addition, police detectives at times interrogate a suspect in Spanish and then have the suspect sign the confession in English.3 Even when an LEP person is sentenced and is serving prison time, his reaction (or lack thereof) to an English-language order from a corrections officer can result in the prisoner receiving an administrative penalty, thus resulting in a negative report alleging disobedience to an order (Petroski 2002). The “Right” to an Interpreter An elusive and at times problematic trial-process issue involves the prosecution of a limited-English-proficient (LEP) accused. American appellate courts have described certain trials involving linguistically challenged persons as meaningless experiences,4 incomprehensible rituals,5 guaranteed confusion,6 and, among other things, a “babble of voices.”7 Those harshly critical and descriptive denunciations are not of some distant police state with no regard for basic human dignity. Instead, they represent the words judges have used to condemn American criminal justice procedures applied to those who lack English fluency (Hench 1999, 252). While some jurists recognize the constitutional dilemmas facing the LEP accused, others minimize its importance (Salinas and Martinez 2010, 543). In a review of the factors and practices that impact the fairness of the trial proceeding, the concern primarily centers on comprehension by the accused of court proceedings and the evidence that is being offered against him. One way to assess one’s comprehension of English is to gauge his English-speaking fluency or ability. A review of judicial decisions depicts how jurists, many of them apparently monolingual English speakers, curiously develop the ability to determine if an LEP person is fluent in English. Of critical importance is the fact that the decision to appoint an interpreter rests within the sound discretion of the trial court.8 The concern is that many jurists abuse that discretion since they do not seek professional assistance in determining the language abilities of the accused. The fundamental dictionary meaning of the word “fluent” indicates that a person is “able to speak a language easily and very well” or has the ability to use a language “clearly and effectively.”9 Yet, court decisions that include only a judge’s conclusory statement of the English linguistic ability of an accused leave much to be desired. To clarify, there is no explicit “right” to an interpreter. Lawyers often speak of this right. To some extent, they are correct. More accurately, the right or rights involved include several related matters that derive from the Sixth Amendment, which provides that in all criminal prosecutions the accused shall first enjoy the right to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; secondly, the right to be confronted with the witnesses against him; and third, the right to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.10 These rights are necessarily compromised if the accused is a non-English speaker or is a deaf-mute. Neither would be able to hear or comprehend the testimony or to communicate with counsel without the assistance of a language interpreter or a specialized sign interpreter.11 For instance, an accused whose exclusive or dominant language is Spanish faces a difficulty in being “informed of the nature” of the accusation and in “confronting” the witnesses against him unless the judge provides an interpreter. Without an interpreter, if a witness testifies falsely or mistakenly, the accused cannot possibly “confront” that person. Under these conditions, as far as the monolingual Spanish speaker is concerned, all he hears is babble, a series of nonsensical and unintelligible sounds coming from the witness. These circumstances easily undercut a person’s constitutional rights and lead to a denial of due process, a deprivation of the right to ordered liberty under the Fourteenth Amendment. The right to the assistance of counsel involves an even more delicate question. Many court observers might think that a judge merely has to appoint a bilingual attorney who can communicate effectively with his client. For practical purposes, the appointment of bilingual counsel does not provide a solution. Clearly, bilingual counsel provides a more helpful and meaningful contribution to the client’s ability to understand the proceedings. During a trial, however, counsel’s role as an interpreter is impossible. Counsel’s primary obligation during a trial is to listen to the witnesses, take notes in preparation for cross-examination, and listen closely in order to stand quickly to make an appropriate objection to impermissibly prejudicial evidence. Failure to object in a timely way generally constitutes a waiver of preservation of an issue for appellate purposes. Consequently, any distraction by a monolingual client who wants to know what the witness is saying will inadvertently result in a relinquishment of his right to the effective assistance of counsel and the loss of the right to confrontation. Additionally, the situation of an accused who cannot comprehend the criminal proceedings for linguistic reasons is analogous to that of a mentally incompetent person who cannot comprehend what is being said and thus cannot possibly cooperate with counsel in his defense.12 Stated another way, the accused is physically present, but he is mentally absent. The right to counsel has been described as perhaps the most “pervasive” of all rights. This right is by far the most all-encompassing right an accused has, because it is through counsel that an accused attains the “ability to assert any other rights he may have” (Schaefer 1956, 8). In situations where the counsel is overcome by additional responsibilities above and beyond those expected of an attorney, the client suffers the consequences. The Dominance of Spanish in the United States While the language spoken could be Chinese, Vietnamese, or Spanish, American demographics involving non-English speakers point substantially to the fast-growing Latino population. Results gleaned from the 2000 Census revealed that approximately 28 million American residents spoke Spanish in the home. Of the nearly 47 million Americans who spoke a foreign language, about 60 percent spoke Spanish (Gopel 2005, 10, 629). The 2010 Census numbers illustrate an increase among Spanish-language speakers, a finding that portends new challenges for the nation’s judicial system. For example, approximately 38 million American residents spoke Spanish in the home. Of the nearly 60 million Americans who spoke a foreign language, the total number who spoke Spanish increased to 62 percent (Ryan 2013, 3). Other pertinent findings from the Spanish-language category include the fact that 17 percent report that they speak English “not very well,” while another 9 percent report speaking English “not at all.” This group of limited-English-proficient Latinos has self-identified as being linguistically challenged. The total numbers are even more revealing: 26 percent of the 50 million Latinos (13 million persons) admit that they cannot function well or at all in English. A significant group among this large population would need interpreter services in all courtrooms of the United States, a factor that is even more significant in our criminal courts, where liberty interests are at stake. Table 1 reveals that the Spanish-language American population has grown incredibly in the last four decades. In 1980, there were about 11 million Latinos who spoke Spanish in the home; today, that number is almost 38 million, an increase of 238 percent (Ryan 2013, 3, 7). Among the recognized languages of the world, Spanish as a first language is spoken by 322 million (Gopel 2005, 729). As a result of immigration and proximity to Latin America, U.S. Latinos will not likely relinquish their Spanish language. To force an adjustment of one’s medium of communication strikes at perhaps the most fundamental civil right of a people. Several factors affect the tenacity of those who speak Spanish. First, a large segment of the Latino population lives along the border with Mexico (and near to Central America), in Florida near Cuba, in Puerto Rico, or in New York City and Chicago, where almost 3 million Latinos reside. Second, Latinos live in concentrated numbers in other urban areas, such as Los Angeles, Houston, San Antonio, and Dallas. Cities like Miami and El Paso have a Latino population that exceeds 65 percent (Gopel 2005, 9). Third, the search for employment takes immigrants and other Latinos further, to even smaller rural areas (McKeown and Miller 2009, 33). Finally, the continued presence of Spanish in our national landscape is obvious in the U.S. television media. In July 2013, Spanish-language television reached a milestone when Univision finished first among broadcast networks during the monthly sweeps in two coveted demographic categories. According to the Nielsen ratings, during a one-month period, Univision exceeded the number of viewers, beating out English-language networks FOX, NBC, CBS, and ABC (Lopez 2013). The Treatment of the Limited English Proficient (LEP) Accused in Criminal Courts The issue of interpreters for non-English speakers has been addressed throughout the United States.13 As early as 1879, the California Supreme Court addressed the criminal case of Jacinto Arao. His trial was conducted entirely in English with no assistance for the exclusively Spanish-speaking accused (Pitt 1966, 70–71). A similar result occurred in a Texas death-penalty case a few years later.14 In the next forty to fifty years, linguistic protections in criminal cases did not improve much.15 Many of the problems centered on the fact that the Latino accused understood some English or spoke some English. Similarly, an Anglo who speaks “some Spanish” will not ipso facto be able to face a trial in Spanish or carry on an intelligible conversation. Neither should a Latino face the impossibility of fully understanding the nature of a criminal accusation and the claims being made by witnesses.16 It was not until State v. Vasquez17 in 1942 that the need for an interpreter began to gain more respect when analyzed from the perspective of the right to confront witnesses who appeared against the accused. Vasquez thus became the first “modern” case where a state court provided protection for a non-English-speaking defendant. Vasquez involved a murder allegation mixed with a self-defense claim.18 Once the first witness began, counsel requested an interpreter because Vasquez was unable to understand the English-speaking witness.19 The judge denied the request because the right to an interpreter “was a right” the defendant was not entitled to in “an English speaking court.”20 Defense counsel called Vasquez as a witness, and he was sworn in, in Spanish. At this point the judge became directly aware of the language barrier, but he tried to continue without an interpreter. When the defendant requested to testify in Spanish, along with an interpreter to aid the English-speaking courtroom participants, the prosecution objected. After the court failed to rule on, or make an inquiry into, the request, the accused retired from the witness stand without testifying.21 The appellate court reversed on the basis of cumulative errors that denied Vasquez a fair trial. Six years later, Garcia v. State22 (“Garcia I”) held that failure to provide an interpreter to an accused who could not understand the language violated his constitutional rights.23 The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals observed that especially in the area along the Rio Grande border, many American citizens include Latin Americans who speak and understand only the Spanish language. The court expressed that these citizens, when they might appear as an accused in a criminal prosecution, are “entitled to be confronted by the witnesses under the same conditions as applied to all others. Equal justice so requires. The constitutional right of confrontation means something more than merely bringing the accused and the witness face to face; it embodies and carries with it the valuable right of cross-examination of the witness.”24 Latinos reside in all parts of the United States, and the constitutional rights to confrontation and to the effective assistance of counsel apply regardless of one’s proximity to the Mexican border. These rights apply similarly to immigrants who have chosen to follow the crops and other employment opportunities, and to U.S. Latinos who have migrated in large numbers in recent decades to states in the South, including Texas, creating a linguistic challenge for the courts in those states. Between 2000 and 2010, Texas experienced the nation’s highest numeric population increase, adding 4.3 million people, for a growth rate of 20.6 percent. Excluding California, the southern states of Florida (2.8 million), Georgia (1.5 million), and North Carolina (1.5 million) represent the third, fourth, and fifth largest population increases respectively (Mackun and Wilson 2011, 2). As to Latino population growth, the numbers in table 2 display the ethnic group’s significant development in several southern states. The table confirms that during this ten-year period, the Latino population in the South increased incredibly. This phenomenon inevitably created a culture shock and a financial drain on the court systems of those states. Many of these new residents are immigrants that follow employment opportunities in the construction, service, and agricultural fields. In this decade, among the southern states, South Carolina and Alabama had the highest Latino increases of 145 percent or more. The table figures also reflect that two states, North Carolina and Georgia, had total Latino populations of 800 and 854 thousand respectively in 2010. After the Vasquez ruling in Utah, twenty-eight years passed before a federal appellate court more analytically addressed the constitutional issues involved. In Negron v. New York, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Negron, an LEP accused, was entitled to the basic right to have the assistance of an interpreter as a means to realize other constitutional rights.25 A native of Puerto Rico, where Spanish is the dominant language, Negron had been in New York only a few months when a verbal dispute led to the fatal stabbing of his roommate. Negron was quickly arrested and charged with murder. At the trial, the government conceded that Negron neither spoke nor understood English. Negron’s court-appointed lawyer spoke no Spanish. Thus, counsel and client could not communicate without the aid of an interpreter. Except for sporadic instances, Negron was unable to participate in any manner in the development of his defense. Through the assistance of an interpreter, Negron’s attorney conferred with him at the jail for some twenty minutes before trial. During the trial, however, the interpreter provided by the prosecution for the Spanish-speaking witnesses did not conduct any contemporaneous interpretation of the English-speaking witnesses for Negron. One of those witnesses, the police officer who interviewed Negron, particularly damaged him by claiming that Negron had admitted the murder. The prosecution’s interpreter merely provided Negron ex post facto summaries of what the witnesses incomprehensibly stated by visiting with him and his lawyer during two short recesses, which lasted about ten to twenty minutes. She summarized the testimony of those witnesses who had already testified in English.26 The appellate court concluded that this Spanish communication after the witnesses had been excused hardly sufficed to apprise Negron with sufficient precision to enable him or his attorney to conduct an effective cross-examination. Upon review of the trial record, the appellate court judge declared: “Not only for the sake of effective cross-examination, however, but as a matter of simple humaneness, Negron deserved more than to sit in total incomprehension as the trial proceeded.”27 The Second Circuit Court of Appeals proceeded to void a state prosecution where a defendant, for practical purposes, is not “present at his own trial.”28 The court added that in order to be considered “present,” the accused should “possess sufficient present ability to consult with his lawyer with a reasonable degree of rational understanding.”29 The appellate decision established that the constitutional right to confront and cross-examine witnesses and to have effective assistance of counsel required the services of a competent interpreter. In Negron, the evidence determined that the accused was not just limited in English proficiency, but in fact limited only to comprehension in Spanish. The court specifically noted how inappropriate it is for a multilingual nation’s criminal justice system callously to prosecute an accused with a “crippling language handicap.”30 Negron thus became a landmark case that set the standard for the rights of non-English speakers to be present at and participate in the court proceedings, to confront the witnesses, and to enjoy the effective assistance of counsel. The well-reasoned opinion perhaps explains why the Supreme Court has never deemed it necessary to address the interpreter issue. The Right to Be Present at One’s Criminal Trial One might be tempted to think that Negron leveled the playing field for the LEP accused. On the contrary, non-English-speaking defendants walk on very perilous ground from the time they are first interrogated to the time they enter the courtroom. This fact is exemplified in a 2004 decision in Texas in another Garcia v. State31 case (Garcia II). Garcia II involved a jury trial with mostly English-speaking witnesses. The proceedings were not translated for the benefit of the Spanish-speaking defendant charged with sexual assault. Garcia entered a plea of not guilty, made bail, and hired an attorney who did not speak Spanish. As a result, Garcia and his attorney were forced to communicate solely through Ms. Montoya, the attorney’s bilingual assistant.32 Montoya sat next to or near Garcia during trial, but she never informed Garcia as to what the witnesses stated. She explained that nobody advised her to interpret, and she feared disrupting the proceedings. The trial judge later commented that towards the middle part of the guilt-innocence stage of the trial, he “noticed that the testimony was not being translated.”33 First, Garcia II decided that merely having the assistant sit next to Garcia did not amount to having an interpreter. Montoya’s bilingual status and proximity to Garcia did not automatically elevate her to the status of courtroom interpreter.34

CHAPTER 9

The Rights of the Limited-English-Proficient Accused in the Criminal Courts