The Law, Economics, and Psychology of Consumer Contracts

1

The Law, Economics, and Psychology of Consumer Contracts

Introduction

Outcomes in consumer markets are the product of interactions between market forces and consumer psychology. Most of this book explores these interactions and their legal policy implications in three consumer markets: credit cards (Chapter 2), mortgages (Chapter 3), and cellular phones (Chapter 4). These three chapters present case studies that expose the unique features of economics–psychology interactions in each market. Indeed, they show that broad generalizations can rarely be drawn, especially when considering if and how the law should intervene in consumer markets.

While each market is unique, a common methodology can be applied to analyze different consumer markets. Such a common methodology—a behavioral-economics methodology—is described in this chapter. The bulk of the analysis is descriptive, examining how market forces interact with consumer psychology to produce observed contract design and pricing structures in the market.1 In this chapter, the descriptive analysis begins with consumer biases and misperceptions and ends with contracts and prices. The goal is to highlight predictions of the behavioral-economics theory. By way of contrast, the case studies presented in the following chapters begin with the observed contract designs and pricing schemes, and then seek a theoretical explanation for the observed contracts and prices. Moreover, the case studies first consider possible rational-choice, neoclassical economics explanations for the observed contracts and prices. The behavioral-economics theory enters only after the standard accounts are shown to be unsatisfactory or incomplete. Indeed, the failure of the standard approach provides the impetus for developing an alternative, behavioral-economics theory.

Following the descriptive analysis, the next step is to explore the normative implications of the outcomes produced by the interaction of market forces and consumer psychology. Are these contracts and prices enhancing or diminishing the welfare of the consumer and of society? As noted in the introduction, when sellers design contracts and prices in response to the demand generated by imperfectly rational consumers, the result is a behavioral market failure. Several common welfare costs associated with this market failure are incurred, including efficiency costs and distributional costs. These welfare costs are often mitigated by market solutions; specifically, learning by consumers and education by sellers. Yet these market solutions are imperfect. Welfare is not maximized. And this opens the door for considering legal policy interventions. The range of possible policy responses is broad and it varies from market to market. Here, and in the remainder of the book, the discussion of policy implications focuses on a single regulatory tool: disclosure mandates.

I. The Behavioral Economics of Consumer Contracts

The behavioral-economics theory rests on two tenets:

(1) Consumers’ purchasing and use decisions are affected by systematic misperceptions

(2) Sellers design their products, contracts, and prices in response to these misperceptions.

That individual decision-making is affected by a myriad of biases and misperceptions is well documented.2 An important question is whether these biases and misperceptions persist in a market context and are large enough to influence market outcomes. As we will see in the following chapters, in many cases the answer to this question is “yes.”

How does consumer psychology influence contract design and pricing structure? The basic claim is that market forces demand that sellers be attentive to consumer psychology. Sellers who ignore consumer biases and misperceptions will lose business and forfeit revenue and profits. Over time, the sellers who remain in the market, profitably, will be the ones who have adapted their contracts and prices to respond, in the most optimal way, to the psychology of their customers. This general argument is developed in Section A below. In particular, the interaction between consumer psychology and market forces results in two common contract design features: complexity and cost deferral. Section B describes these features and explains why they appear in many consumer contracts.

A. Designing Contracts for Biased Consumers

1. General

It is useful to start by reciting the standard, rational-choice framework. This standard framework will then be adjusted to allow for the introduction of consumer biases and misperceptions. Juxtaposing the standard and behavioral frameworks will help compare market outcomes under the two models.3

In the rational-choice framework, a consumer contract provides the consumer with an expected benefit, B, in exchange for an expected price, P. As elaborated below, both the benefit and the price can be multidimensional. The number of units sold, which will be referred to as the demand for a seller’s product, D, is increasing in the benefit that the product provides, B, and decreasing in the price that the seller charges, P. Demand is a function of benefits and prices: D(B, P). The seller’s revenue is determined by the number of units sold, namely, the demand for the product multiplied by the price per unit. The seller’s profit is equal to revenue minus cost.

When consumers are imperfectly rational, suffering from biases and misperceptions, this general framework must be extended as follows: There is a perceived expected benefit, ![]() , which is potentially different from the actual expected benefit, B. Similarly, there is a perceived expected price,

, which is potentially different from the actual expected benefit, B. Similarly, there is a perceived expected price, ![]() , which is potentially different from the actual expected price, P. Demand is now a function of perceived benefits and prices, rather than of actual benefits and prices: D(

, which is potentially different from the actual expected price, P. Demand is now a function of perceived benefits and prices, rather than of actual benefits and prices: D(![]() ,

,![]() ). Revenues—and profits—are a function of perceived benefits and prices, which affect the demand for the product, and of the actual price.

). Revenues—and profits—are a function of perceived benefits and prices, which affect the demand for the product, and of the actual price.

Before proceeding further, the relationship between imperfect information and imperfect rationality should be clarified. Rational-choice theory allows for imperfect information. A divergence between perceived benefits and prices on the one hand and actual benefits and prices on the other is also possible in a rational-choice framework with imperfectly informed consumers. The focus here, however, is on systemic under- and overestimation of benefits and prices. Perfectly rational consumers will not have systemically biased beliefs; imperfectly rational consumers will. The main difference is in how perfectly and imperfectly rational consumers deal with imperfect information. Rational-choice decision-making provides tools for effectively coping with imperfect information. These tools are not used by the imperfectly rational consumer. Instead, he relies on heuristics or cognitive rules-of-thumb, which result in predictable, systemic biases and misperceptions.4

Sellers must keep costs down and revenues up to maximize profits. As we have seen, revenues are the product of the number of units sold, or the demand for the product, multiplied by the price per unit. These observations imply two tradeoffs that determine the seller’s strategy in a rationalchoice framework: First, the seller wants to increase the benefits from the product in order to increase demand, but increased benefits usually entail increased costs. The seller will, therefore, increase the benefits only if the resulting revenue boost more than compensates for the increased costs. The second tradeoff focuses on the price: a lower price increases demand, but also decreases the revenue per unit sold. The seller will set prices that optimally balance these two effects.5

The tradeoffs that determine a seller’s optimal strategy when facing rational consumers are muted in the behavioral-economics model with imperfectly rational consumers. When perceived benefit is different from actual benefit, a seller may be able to increase demand by raising the perceived benefit without incurring the added cost of raising the actual benefit. Similarly, when the perceived price is different from the actual price, demand can be increased by lowering the perceived price, while keeping revenue per unit up with a high actual price. Sellers benefit from the divergence between perceived and actual benefits and between perceived and actual prices. They will design their contracts and prices to maximize this divergence.

2. The Objects of Misperception: Product Attributes and Use Patterns

When consumers are imperfectly rational, demand, D(![]() ,

,![]() ), increases with perceived benefit and decreases with perceived price. The problem is that consumers will overestimate the total benefit and underestimate the total price, resulting in artificially inflated demand.6 Why would a consumer overestimate benefits and underestimate prices? To answer this question, we must identify the factors that determine these benefits and prices. Moreover, as explained below, identifying the objects of misperception will prove important to the welfare and policy analysis presented in the latter half of this chapter.

), increases with perceived benefit and decreases with perceived price. The problem is that consumers will overestimate the total benefit and underestimate the total price, resulting in artificially inflated demand.6 Why would a consumer overestimate benefits and underestimate prices? To answer this question, we must identify the factors that determine these benefits and prices. Moreover, as explained below, identifying the objects of misperception will prove important to the welfare and policy analysis presented in the latter half of this chapter.

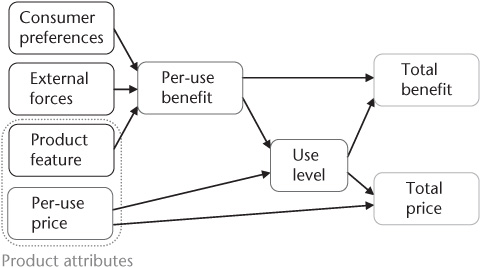

Benefits and prices are a function of product attributes and use patterns. Product attributes define what a product is and what it does. They include product features, contract terms, and prices. For example, the credit limit (a product feature) and the interest rate (a price term) are attributes of the credit card product. Product attributes affect the total benefit and total price. Misperceptions about product attributes lead to misperceptions of the total benefit and total price.

While product features define what a product is and what it does, use patterns define how the product is used. A credit card’s borrowing feature, for example, is used frequently by some consumers and less frequently by others. Some borrow heavily, while others not at all. Product use is clearly affected by the product’s attributes. But, as detailed below, use patterns are also affected by other factors. Product use affects the total benefit and total price. Misperceptions about use patterns lead to misperceptions of the total benefit and total price.

Given the importance of use patterns, it is worthwhile to conceptualize the total benefit as a function of the per-use benefit and use level. Similarly, it is helpful to conceptualize the total price as a function of the per-use price and the use level.7

The total benefit will be overestimated when a consumer overestimates the per-use benefit or use level. For example, the total benefit of a credit card’s borrowing feature will be overestimated if the consumer overestimates the benefit-per-dollar borrowed. The total benefit will also be overestimated if the consumer overestimates how much he will borrow.

In this same way, the total price will be underestimated when a consumer underestimates the per-use price or use level. The total amount paid in interest will be underestimated if the consumer underestimates the interest rate, which can be viewed as the per-use price—the price per dollar borrowed. The total amount paid in interest will also be underestimated if the consumer underestimates how much he will borrow.

Benefit misperception, then, is a function of misperceived per-use benefits or misperceived use levels while price misperception is a function of misperceived per-use prices or misperceived use levels.

Let’s dig deeper: Why would a consumer misperceive the per-use benefit or per-use price? Why would a consumer misperceive the intensity with which he will use the product, or a product feature?

To understand why the per-use benefit might be misperceived, one must identify the underlying forces affecting the per-use benefit. Misperception of any of these underlying forces will result in misperception of the per-use benefit. Consider a credit card’s borrowing feature. The benefit of this feature is a function of the feature itself: Some cards allow for more borrowing, setting a higher credit limit, while others are more restrictive, setting a lower credit limit. The per-use benefit from borrowing drops to zero when the credit limit is reached. The benefit from borrowing is also a function of the consumer’s intertemporal preferences: Some consumers are more willing than others to finance present consumption with debt. Finally, the benefit of borrowing is a function of external forces affecting the consumer’s desire or need to borrow, such as present and expected available income and conditions affecting the demand for funds, for example illness or unemployment. The per-use benefit from the credit card’s borrowing feature will be misperceived when the consumer misperceives the credit limit, his own preferences, or the strength of external forces that create a desire or need to borrow.

Next, the per-use price. The per-use price is set by the seller. Some prices are simple, one-dimensional prices. For example, suppose a movie ticket costs $12. Such a price will rarely be misperceived. Other prices are complex and multidimensional. Think of an adjustable interest rate, subject to different caps for per-period changes and various rate-increasing triggers. It is not hard to see how a consumer might come to misperceive the per-use price—the interest rate applicable to a dollar borrowed.

Finally, use levels. The decision on how often to use a product or product feature is influenced by the per-use benefit and per-use price. A higher benefit-per-dollar borrowed (as, for example, when the consumer is between jobs) will induce more borrowing. A lower interest rate will similarly result in more borrowing. The use-level choice might also be influenced by imperfect rationality. For example, consider a credit card feature that allows the consumer to pay late—a feature that provides potential liquidity benefits to the rational consumer. This feature will be “used” more often by imperfectly rational consumers who forget to pay on time. Misperception of any of the factors that influence the per-use benefit or the per-use price will result in misperception of the use level. A failure to recognize one’s imperfect rationality will also result in misperception of use levels. In our example, a consumer who underestimates his forgetfulness will underestimate the likelihood of “using” the credit card’s late payment feature.

The objects of misperception can now be summarized and categorized. The first category includes product attributes. These are product features and per-use prices determined by the seller when designing the product, contract, and pricing scheme. A consumer makes a product-attribute mistake by misperceiving a product feature or a per-use price. As shown above, product-attribute mistakes can result in misperception of both the total benefit and total price.

Figure 1.1. Factors affecting the total price and total benefit

The second category of objects of misperception includes use levels. Different product features can be used with different degrees of intensity. Consumers often misperceive these use levels. As explained above, how a product is used is a function of product attributes—product features and per-use prices—and of other factors that influence the per-use benefit (and also other factors that influence the use decision, such as forgetfulness). Product-use mistakes, or use-pattern mistakes, can result in misperception of both the total benefit and total price.

This analysis is presented graphically in Figure 1.1, which shows how product attributes affect total benefit and total price, working through the per-use benefit, the use level, or both. Figure 1.1 also shows the central role of use levels in determining the total benefit and total price. Since the total benefit and total price are a function of product attributes and of use levels, misperceptions of product attributes and use level mistakes result in misperceptions of the total benefit and total price.

The distinction between product attributes and use levels will prove central to the welfare and policy implications discussed in subsequent sections. As we’ll see, market forces are less effective in curing product-use mistakes, suggesting that we should be more concerned about such mistakes. Correspondingly, the policy prescriptions outlined in Part IV emphasize the importance of disclosure mandates that incorporate product-use information.

Despite their importance, product-use information and product-use mistakes have received little attention. Moreover, at the policy level, disclosure regulation has focused largely on product-attribute information. The implicit assumption seems to have been that use patterns, being a function of consumer preferences, are known to consumers. But the preceding analysis showed that product use is also a function of product attributes and external forces about which consumers might be imperfectly informed. Moreover, veering away from rational-choice theory, perfect knowledge of one’s preferences cannot simply be assumed. The central role of use levels as an object of misperception thus highlights the value of a behavioral-economics approach.

3. A Simple Example

a. Setup

A consumer obtains a credit card. The consumer uses the card for transacting only, intending to pay the full balance each month. This consumer, however, is a bit forgetful. Specifically, he will miss the payment due date exactly one time each year.

The credit card issuer incurs a fixed annual cost of 4, which represents a general account maintenance cost. The issuer also incurs a variable, or peruse, cost of 2 for each late payment. This represents the cost of processing a late payment and the added risk of default implied by a late payment.

The issuer is contemplating a two-dimensional pricing scheme, including an annual fee (p1) and a late fee (p2). The total price equals the annual fee plus the late fee: p1 + p2. More generally, when the number of late payments can vary—some consumers never pay late, some pay late once, some pay late twice, and so on—the total price would equal the annual fee plus the late fee multiplied by the number of late payments. (The late fee is the per-use price of the late payment feature; the number of late payments is the use level.)

b. Misperceptions

A sophisticated, perfectly rational, consumer realizes that he will pay late once a year and incur a late fee. The sophisticated consumer accurately perceives the total price to be p1 + p2. An imperfectly rational, naive consumer, on the other hand, underestimates his forgetfulness and mistakenly believes that he will never pay late and never incur a late fee. The total price, as perceived by the naive consumer, is p1. This divergence between the actual and perceived total price will affect the equilibrium pricing scheme.

c. Contract Design

Now let’s consider how the issuer will design the credit card contract. How will the magnitudes of the annual fee (p1) and late fee (p2) be determined? The answer depends on consumer psychology and market structure. For ease of exposition and to focus attention on the effect of consumer misperception, assume that the issuer is operating in a competitive market and thus will set prices that just cover the cost of providing the credit card.

Recall that the issuer faces a fixed annual cost of 4 and a variable cost of 2 per incidence of late payment. Accordingly, the efficient contract sets p1 = 4 and p2 = 2. By setting each price equal to the corresponding cost, the (4,2) contract provides optimal incentives and thus maximizes value. The issuer will offer the efficient (4,2) contract to the sophisticated consumer who realizes that there will be one late payment. This contract minimizes the total price paid by the consumer, 4 + 2 = 6, while still covering the issuer’s costs. In fact, in this simple example any set of prices, p1 and p2, such that p1 + p2 = 6, would similarly cover the seller’s costs and minimize the total price paid by the consumer. In a more general example, the (4,2) contract would be uniquely efficient.8

The efficient (4,2) contract will not be offered to a naive consumer—the consumer who mistakenly believes that he will never make a late payment or incur a late fee. For such a consumer, the perceived total price under the (4,2) contract is 4. The efficient (4,2) contract will not be offered in equilibrium, because other contracts appear more attractive to the naive consumer, while still covering the issuer’s costs. Consider the (0,6) contract. With this contract, the imperfectly rational, naive consumer perceives a total price of 0, while the actual price is 6. The naive consumer will thus prefer the (0,6) contract over the efficient (4,2) contract.

In this example, the underestimation of forgetfulness results in underestimation of use levels. Contract design amplifies the effect of this product-use mistake on the perceived total price. In other words, contract design is used to minimize the perceived total price by amplifying the effect of product-use mistakes. When the perceived likelihood of triggering a certain price dimension—such as a late fee—goes down, the magnitude of the corresponding price—the late fee—goes up. Non-salient prices rise, while salient prices are reduced. A price is non-salient, because consumers think it will never be triggered or because the issue (for example, the possibility of paying late) never crosses the consumer’s mind.

4. The Limits of Competition

It is widely believed that competition among sellers ensures efficiency and maximizes welfare. This belief is manifested, for example, in antitrust law and its focus on monopolies and cartels. Competition is also supposed to help consumers by keeping prices low.

The behavioral-economics model emphasizes the limits of competition. The example studied in the previous subsection assumed perfect competition. But we saw that, in equilibrium, sellers offered an inefficient contract and consumer welfare was not maximized. The reason is straightforward: Competition forces sellers to maximize the perceived (net) consumer benefit. When consumers accurately perceive their benefits, competition will help consumers. But when consumers are imperfectly rational, competition will maximize the perceived (net) benefit at the expense of the actual (net) benefit.

Focusing on price: When consumers are perfectly rational, sellers compete by offering a lower price. When consumers are imperfectly rational, sellers compete by designing pricing schemes that create an appearance of a lower price. The underlying problem is on the demand side of the market; imperfectly rational consumers generate biased demand. Competition forces sellers to cater to this biased demand. The result: A behavioral market failure.

Modern, neoclassical economics recognizes that even perfectly competitive markets can fail, because of externalities and asymmetric information. Behavioral economics adds a third cause for market failure; misperception and bias. This behavioral market failure is a direct extension of the imperfect information problem. Rational consumers form unbiased estimates of imperfectly known values. Faced with similarly limited information, imperfectly rational consumers form biased estimates. Unbiased estimates can cause market failure; biased estimates can cause market failure.

The preceding analysis, and the failure of competition that it predicts, takes consumers’ biases and misperceptions as exogenously given. But perceptions and misperceptions can be endogenous. In particular, sellers can influence consumer perceptions. That’s a big part of what marketing is about. What role does competition play in such cases? On the one hand, sellers might try to exacerbate biases that increase the perceived benefit and reduce the perceived price of their products.9 On the other hand, sellers offering superior, yet underappreciated products and contracts may try to compete by educating consumers and fighting misperception. (See Section III.B below for further discussion.)

5. Consumer Heterogeneity

Not all consumers are similarly biased. While some consumers overestimate the net benefit from a product, others might underestimate it. And some consumers accurately perceive benefits and prices. How does this heterogeneity affect the incidence and severity of behavioral market failures?

Contracts are most likely to be designed in response to consumer psychology when many consumers share a common bias. But sellers will design contracts in response to consumer misperception even when different consumers suffer from different misperceptions. In some cases, sellers will be able to identify the different consumer groups and their respective biases and design different contracts for each group. In other cases, sellers will be unable to distinguish between the different groups of consumers ex ante. Still, sellers will be able to offer a menu of contracts. Different contracts in the menu will be attractive to different groups of consumers, according to their specific biases and misperceptions.

B. Common Design Features

The interaction between consumer psychology and market forces influences the design of contracts and pricing schemes. In practice, this influence plays out most often in two common design features: complexity and deferred costs. These design features will figure prominently in the three case studies we’ll examine in later chapters. This section defines and illustrates complexity and deferred costs as contract design features and explains why these design features figure prominently in consumer contracts.10

1. Complexity

Most consumer contracts are complex, offering multidimensional benefits and charging multidimensional prices. Complexity and multidimensionality can be both efficient and beneficial to consumers. Compare a simple credit card contract with only an annual fee and a basic interest rate for purchases to a complex credit card contract that, on top of these two price dimensions, adds a default interest rate, a late fee, and a cash-advance fee. The complex card facilitates risk-based pricing and tailoring of optional services to heterogeneous consumer needs. The default interest rate and the late fee allow the issuer to increase the price for riskier consumers. Such efficient risk-based pricing is impossible with the simple card. Instead, the single interest rate implies cross-subsidization of high-risk consumers by low-risk consumers. Similarly, the cash-advance fee allows the issuer to charge separately for cash-advance services, which benefit some consumers but not others. Such tailoring of optional services is impossible with the simple card. Instead, a higher annual fee implies cross-subsidization of consumers who use the cash-advance feature by those who do not.

These efficiency benefits explain some of the complexity and multidimensionality found in consumer contracts. But there is another, behavioral explanation. Complexity hides the true cost of the product from the imperfectly rational consumer. A rational consumer navigates complexity with ease, assessing the probability of triggering each rate, fee, and penalty, and then calculating the expected cost associated with each price dimension. The rational consumer may have imperfect information, but will nonetheless form unbiased estimates given the information he or she chooses to collect. Accordingly, each price dimension will be afforded the appropriate weight in the overall evaluation of the product.

The imperfectly rational consumer, on the other hand, is less capable of such an accurate assessment. He is unable to calculate prices that are indirectly specified through complex formulas. Even if he could perform this calculation, he would be unable to simultaneously consider multiple price dimensions. And even if he could recall all the price dimensions, he would be unable to calculate the impact of these prices on the total cost of the product. Bottom line: The imperfectly rational consumer deals with complexity by ignoring it. He simplifies his decision by overlooking non-salient price dimensions.11 And he approximates, rather than calculates, the impact of the salient dimensions that cannot be ignored.

In particular, consumers with limited attention and limited memory exclude certain price dimensions from consideration. In addition, limited processing ability prevents consumers from accurately aggregating the different price components into a single, total expected price that would serve as the basis for choosing the optimal product. So while complexity may not faze the rational consumer, it will most likely mislead the imperfectly rational consumer.

As explained above, sellers design contracts in response to systematic biases and misperceptions of imperfectly rational consumers. In particular, they reduce the total price, as perceived by consumers, by decreasing salient prices and increasing non-salient prices. This strategy depends on the existence of non-salient prices. In a simple contract, the one or two price dimensions will generally be salient. Only a complex contract will have both salient and non-salient price dimensions. Complexity thus serves as a tool for reducing the perceived total price.

Moreover, complexity will increase over time as consumers learn to incorporate more price dimensions into their decision. If sellers significantly increase the magnitude of a non-salient price dimension, consumers will eventually learn to focus on this price dimension, making it salient. Sellers then will have to find another non-salient price dimension. When they run out of non-salient prices in the existing contractual design, they may create new ones by adding more interest rates, fees, or penalties.12

Another common tactic for increasing complexity is bundling. An example is the bundling of handsets and cellular service, cemented with lock-in contracts and early termination fees. This bundle naturally includes multidimensional pricing; specifically, the price of the handset and the pricing scheme for cellular service (which is itself rather complex). Arguably, one of the main goals of bundling is to create a low perceived total price by reducing the salient handset price and increasing the non-salient pricing of cellular service. This pricing strategy could not work without bundling: Carriers need the high service prices to compensate for the low, below-cost handset prices. Without bundling, consumers would buy the low-price handset from one seller and get service from a competing carrier, and the practice of offering below-cost handset prices would soon come to an end. There are many other examples of bundling: The credit card bundles transacting and borrowing services. Subprime mortgage contracts bundle secured credit with inspection, appraisal, and insurance services.

In addition to increasing complexity, bundling is used to create deferred-cost contract designs. This occurs when a product or service with short-term benefits and prices is bundled with a product or service with long-term benefits and prices. In the handsets and cellular service example, bundling both increases complexity and facilitates cost deferral.13

The focus, thus far, has been on intra-contract complexity. A broader perspective reveals that a consumer’s decision process is far more complicated than sorting through the complexity of any single contract. Consumers today must choose from among many complex products offered by competing sellers. At first glance, more choice is better. Consumers are heterogeneous, so more products mean that consumers can find the product that best suits their individual needs. But there’s a catch: Searching for the right product among a complex maze of complex products is costly, even for rational consumers. Imperfect rationality exacerbates this cost and may even discourage consumers from searching altogether. More choice comes at the expense of meaningful choice.

A clarification is in order: In theory, an incomplete understanding of complex contracts is consistent with rational-choice theory. Facing a complex contract, a rational consumer would have to spend time reading the contract and deciphering its meaning. If the cost of attaining perfect information and perfect understanding of the contract is high, the rational borrower would stop short of this theoretical ideal. Imperfect rationality can be viewed as yet another cost of attaining more information and better understanding. When this cost component is added, the total cost of becoming informed goes up, and thus the consumer will end up with less information and a less complete understanding of the contract. Imperfect rationality, however, is not simply another cost component. Rational consumers who decide not to invest in reading and deciphering certain contractual provisions will not assume that these provisions are favorable; in fact, they will recognize that unread provisions will generally be pro-seller. In contrast, imperfectly rational consumers will completely ignore the unread or forgotten terms or naively assume that they are favorable. Accordingly, a complex, unread term or a hidden fee would lead an imperfectly rational consumer—but not a rational consumer—to underestimate the total cost of the product. As a result, the incentive to increase complexity and hide fees will be stronger in a market with imperfectly rational consumers. The behavioral-economics theory of contract design is an imperfect-rationality theory, not an imperfect-information theory.

2. Deferred Costs

Non-salient price dimensions and prices that impose underestimated costs create opportunities for sellers to reduce the perceived total price of their product. What makes a price non-salient? What leads consumers to underestimate the cost associated with a certain price dimension? While there are no simple answers to these questions, there is one factor that exerts substantial influence on both salience and perception; time.

The basic claim is that, in many cases, non-contingent, short-run costs are accurately perceived, while contingent, long-run costs are underestimated. An annual fee is a non-contingent price that needs to be paid, by a specific date in the near future, regardless of how the consumer uses the card. This cost will figure prominently into the consumer’s selection from among competing cards. A late fee, on the other hand, is a contingent price that will be paid in the more distant and unspecified future only if the consumer makes a late payment. This cost, as we have seen, will often be underestimated by the consumer and is, therefore, less likely to affect card choice. If costs in the present are accurately perceived and future costs are underestimated, market forces will produce deferred-cost contracts.

The importance of the temporal dimension of price and cost can often be traced back to two underlying forces; myopia and optimism. Myopic consumers care more about the present and not enough about the future. It is rational to discount future costs and benefits by the probability that they will never materialize. It is also rational to consider the time-value of money; a tax or price deferred is a tax or price saved. It is not rational to discount the future simply because it is in the future or because the future seems less real, or harder to picture. Myopia is excessive discounting.

Myopia is common. People are impatient, preferring immediate benefits even at the expense of future costs.14 Myopia is attributed to the triumph of the affective system, which is driven primarily by short-term payoffs, over the deliberative system, which cares about both short-term and longer-term payoffs. This understanding of myopia, and of intertemporal choice more generally, is consistent with findings from neuroscience.15

Future costs are also often underestimated because consumers are optimistic. The prevalence of the optimism bias has been confirmed in multiple studies.16