The international crime of torture

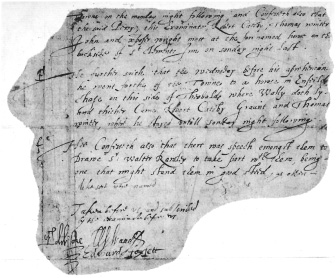

Chapter 4 We saw above that some human rights violations give rise to individual criminal responsibility. We have referred to war crimes and set out the definitions of genocide and crimes against humanity. Such crimes have sometimes been prosecuted in international tribunals and, on occasion, at the national level. Another international crime is the crime of torture. The prohibition on torture in the UN Convention against Torture is described in absolute terms. (‘No exceptional circumstances whatsoever, whether a state of war or a threat of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked as a justification of torture.’) But we know that torture unfortunately goes on around the world. In this short chapter, we will focus on four issues: the definition of torture, the arguments that have been put forward to excuse torture in order to prevent a terrorist attack, the prohibition of the use of evidence gleaned from torture, and the ban on sending someone to a country where there is a strong likelihood of them being tortured. It is suggested we can learn a lot about the foundations of human rights thinking from the exploration of these issues. To better understand the challenges involved, it is worth recalling a little of the history of torture. The purposes of torture have been various. In some contexts torture was considered a useful way to extract confessions and essential proof for a conviction at trial. Although the English common law prohibited torture, an exceptional procedure allowed the king to issue ‘torture warrants’ through the Star Chamber. One of the most famous individuals subjected to this procedure was Guy Fawkes, caught trying to blow up the Houses of Parliament in 1605. He was then tortured into giving up the names of his accomplices. The judges of the House of Lords in a recent human rights case have reminded us of this episode in English history (see Box 16). This form of investigation became seen as emblematic of the abuse of power by the King, it was therefore abolished, along with the Star Chamber, in 1640. Although the Roman-Canon law tradition in Continental Europe continued to accept confessions extracted by torture as useful elements of proof, this practice was increasingly seen, not only as unreliable, but also as unfair to the innocent. 9. Guy Fawkes’s confession, extracted by torture. His shaky signature can barely be made out at the end of the confession and above the signature of the witnesses

The international crime of torture

Box 16: Lord Hope in A v Secretary of State for the Home Department (2005)

Four hundred years ago, on 4 November 1605, Guy Fawkes was arrested when he was preparing to blow up the Parliament which was to be opened the next day, together with the King and all the others assembled there. Two days later James I sent orders to the Tower authorising torture to be used to persuade Fawkes to confess and reveal the names of his co-conspirators. His letter stated that ‘the gentler tortours’ were first to be used on him, and that his torturers were then to proceed to the worst until the information was extracted out of him. On 9 November 1605 he signed his confession with a signature that was barely legible and gave the names of his fellow conspirators. On 27 January 1606 he and seven others were tried before a special commission in Westminster Hall. Signed statements in which they had each confessed to treason were shown to them at the trial, acknowledged by them to be their own and then read to the jury.

In modern times we have seen how brutal regimes considered that torture would remind dissidents and the general population who was in charge – and who was determined to remain in charge. In the 1980s, an anti-torture campaign, led by groups such as Amnesty International, was successful in advocating a set of binding international prohibitions on torture. Torture was already criminalized as a war crime when committed against certain prisoners, and was considered an international crime in the context of genocide and crimes against humanity. But the 1984 Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment criminalized torture even outside these contexts, and prescribed individual criminal responsibility for a single act of torture. As already mentioned, Senator Pinochet’s arrest and detention in London resulted from the application of the rules contained in this Convention and, more recently, we have seen this treaty provide the context for the arrest in Senegal of the former President of Chad, Hissène Habré, with a view to his eventual prosecution for crimes of torture. In 2005, the Afghan rebel leader, Faryadi Zardad, was convicted at the Old Bailey in London of torture and hostage-taking and sentenced to 20 years imprisonment. This represented a rare, but concrete, implementation of the torture treaty.

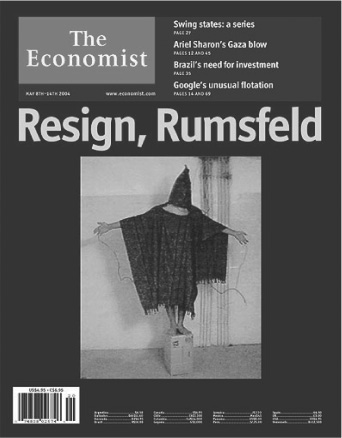

10. Images of the abuse and humiliation of Iraqi prisoners were flashed around the world. The photo of the hooded man on a box with electrical wires became emblematic of the human rights abuses committed against prisoners in Iraq

By December 2004, the US Justice Department had replaced the previous memorandum with a public document setting out the US policy and abandoning the idea of such an explicit threshold. Instead, the memorandum details those cases of foreign abuse that had been determined as torture by judicial decisions in the United States. These cases were suits brought against foreign torturers from the Philippines, Iraq, and Iran (see Box 17).

Box 17: From the US Department of Justice memorandum, 2004

Cases in which courts have found torture suggest the nature of the extreme conduct that falls within the statutory definition. See, e.g., Hilao v Estate of Marcos, [1996] … (concluding that a course of conduct that included, among other things, severe beatings of plaintiff, repeated threats of death and electric shock, sleep deprivation, extended shackling to a cot (at times with a towel over his nose and mouth and water poured down his nostrils), seven months of confinement in a ‘suffocatingly hot’ and cramped cell, and eight years of solitary or near-solitary confinement, constituted torture); Mehinovic v Vuckovic, [2002] … (concluding that a course of conduct that included, among other things, severe beatings to the genitals, head, and other parts of the body with metal pipes, brass knuckles, batons, a baseball bat, and various other items; removal of teeth with pliers; kicking in the face and ribs; breaking of bones and ribs and dislocation of fingers; cutting a figure into the victim’s forehead; hanging the victim and beating him; extreme limitations of food and water; and subjection to games of ‘Russian roulette’, constituted torture); Daliberti v Republic of Iraq, [2001] … (entering default judgment against Iraq where plaintiffs alleged, among other things, threats of ‘physical torture, such as cutting off … fingers, pulling out … fingernails’, and electric shocks to the testicles); Cicippio v Islamic Republic of Iran, [1998] … (concluding that a course of conduct that included frequent beatings, pistol whipping, threats of imminent death, electric shocks, and attempts to force confessions by playing Russian roulette and pulling the trigger at each denial, constituted torture).