THE EUROPEAN CONTEXT

THE EUROPEAN

CONTEXT15

15.1 INTRODUCTION

As was stated in Chapter 3, it is unrealistic and indeed impossible for any student of English law and the English legal system to ignore the UK’s membership of the European Union (EU). Nor can the impact of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) be ignored, especially now that the Human Rights Act (HRA) 1998 has made the Articles of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) directly applicable in the UK.

It is also essential to distinguish between the two different courts that operate within the European context: the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), formerly the European Court of Justice (ECJ), which is the court of the EU, sitting in Luxembourg; and the ECtHR, which deals with cases relating to the ECHR and sits in Strasbourg.

The development of the European Union

The long-term process leading to the, as yet still to be attained, establishment of an integrated EU was a response to two factors: the disasters of the Second World War; and the emergence of the Soviet Bloc in Eastern Europe. The aim was to link the separate European countries, particularly France and Germany, together in such a manner as to prevent the outbreak of future armed hostilities. The first step in this process was the establishment of a European Coal and Steel Community. The next step towards integration was the formation of the European Economic Community (EEC) under the Treaty of Rome in 1957. The UK joined the EEC in 1973. The Treaty of Rome has subsequently been amended in the further pursuit of integration as the Community has expanded. Thus, the Single European Act (SEA) 1986 established a single economic market within the EC and widened the use of majority voting in the Council of Ministers. The Maastricht Treaty further accelerated the move towards a federal European supranational State, in the extent to which it recognised Europe as a social and political – as well as an economic – community. Previous Conservative governments of the UK resisted the emergence of the EU as anything other than an economic market and objected to, and resiled from, various provisions aimed at social, as opposed to economic, affairs. Thus, the UK was able to opt out of the Social Chapter of the Treaty of Maastricht. The new Labour administration in the UK had no such reservations and, as a consequence, the Treaty of Amsterdam 1997 incorporated the European Social Charter into the EC Treaty which, of course, applies to the UK (see below).

As the establishment of the single market within the European Community progressed, it was suggested that its operation would be greatly facilitated by the adoption of a common currency, or at least a more closely integrated monetary system. Thus, in 1979, the European Monetary System (EMS) was established, under which individual national currencies were valued against a nominal currency called the ECU and allocated a fixed rate within which they were allowed to fluctuate to a limited extent. Britain was a member of the EMS until 1992, when financial speculation against the pound forced its withdrawal. Nonetheless, other members of the EC continued to pursue the policy of monetary union, now entitled European Monetary Union (EMU), and January 1999 saw the installation of the new European currency, the Euro, which has now replaced national currencies within what is now known as the Eurozone. The UK did not join the EMU at its inception and there is little chance that membership will appear on the political agenda for the foreseeable future, especially given the financial crisis that is enveloping many of the EMU states, particularly those on the periphery of the EU. It remains to be seen whether the ongoing financial crisis results in the break-up of the EMU, or its strengthening, as the current members may be forced to seek more economic unity to address its consequences.

In December 2000 the European Council met in Nice in the south of France. The Council consists of the heads of state or government of the member countries of the EU, and is the body charged with the power to make amendments to EU treaties (see below). The purpose of the meeting was to prepare the Union for expansion from its then 15 to 25 members by the year 2004, and so to its current 27 members. New members ranged from the tiny Malta with a population of 370,000 to Poland with its population of almost 39 million people. In order to accommodate this large expansion, it was recognised that significant changes had to be made in the institutions of the current Union, paramount among those being the weighting of the voting power of the Member States. Although parity was to be. maintained between Germany, France, Italy and the UK at the new level of 29 votes, Germany and any two of the other largest countries gained a blocking power on further changes, as it was accepted that no changes, even on the basis of a qualified majority vote, could be introduced in the face of opposition from countries constituting 62 per cent of the total population of the Union. The recognition of such veto power was seen as a victory for national as against supranational interests within the Union and a significant defeat for the Commission. However, the number of matters subject to qualified majority voting was increased, although a number of countries, including the UK, refused to give up their veto with regard to the harmonisation of national and corporate tax rates. Nor would the UK, this time supported by Sweden, agree to give up the veto in relation to social security policy. Core immigration was another area in which the UK government retained its ultimate veto.

At the same time as these changes were introduced, the members of the Council of Europe also signed a new charter of fundamental rights. Among the rights recognised by the charter are included:

• right to life;

• respect for private and family life;

• protection of family data;

• right to education;

• equality between men and women;

• fair and just working conditions;

• right to collective bargaining and industrial action;

• right not to be dismissed unjustifiably.

It is significant that the charter was not included within the specific Treaty issues at Nice at the demand of the UK. The UK had also ensured that some of the references, particularly to employment matters, were subject to reference to domestic law.

In June 2001, Ireland caused a furore within the EU when its voters declined to ratify the Nice Treaty in a referendum. Perhaps not surprisingly, given the sensitivity of the issue, Ireland was the only member state which made ratification a matter for its electorate, all the other member states preferring to ratify the Treaty through their Parliaments. Following the vote, strong pressure was placed on the Irish government to ensure ratification at a later date, and at the Gothenburg summit meeting in the same month, the leaders of the EU made it clear that the expansion of the EU was irreversible. In 2002, the Irish electorate ratified the Treaty.

Although the Treaty of Nice was difficult and time-consuming in its formation, it looked for some time that its terms would be replaced before they had actually come into effect. This possibility came about as a result of the conclusions of the Convention on the Future of Europe, which was constituted in February 2002 by the then members to consider the establishment of a European Constitution. The Convention, which sat under the presidency of the former President of France, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, produced a draft constitution, which it was hoped would provide a more simple, streamlined and transparent procedure for internal decision-making within the Union and to enhance its profile on the world stage. Among the proposals for the new constitution were the following:

• the establishment of a new office of President of the European Union;

• the appointment of an EU foreign minister;

• the shift to a two-tier Commission;

• fewer national vetoes;

• increased power for the European Parliament;

• simplified voting power;

• the establishment of an EU defence force by ‘core members’;

• the establishment of a charter of fundamental rights.

In the months of May and June 2005 the move towards the European Constitution came to a juddering halt when first the French and then the Dutch electorates voted against its implementation. Such a signal failure meant that it was not necessary for the UK government to conduct a referendum on the proposed constitution as it had promised. However, as with most EU initiatives, the new constitution did not disappear and re-emerged as the Treaty of Lisbon, signed by all the members in December 2007. Once again the UK government, together with the Polish one, insisted that a protocol, number 7, be appended to the treaty ensuring that the charter of fundamental rights could not create new rights in the UK. As usual the treaty had to be ratified by the members in the course of the next two years. The Lisbon Treaty gave rise to much ill-feeling in many states for the reason that it incorporated most of the proposals originally contained in the previously rejected constitutional proposal. In legal form, the Lisbon Treaty merely amended the existing treaties, rather than replacing them as the previous constitution had proposed. In practical terms, however, all the essential changes that would have been delivered by the constitution were contained in the treaty – a fact widely recognised by some EU leaders, although not the UK’s. Thus Angela Merkel, Chancellor of Germany, was quoted in June 2007, in the Daily Telegraph as saying, ‘The substance of the Constitution is preserved. That is a fact’ and Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, Chairman of the Convention on the Future of Europe which drafted the Constitution was quoted, in a European Parliament press release on 17 July 2007, as saying, ‘In terms of content, the proposals remain largely unchanged, they are simply presented in a different way … This text is, in fact, a rerun of a great part of the substance of the Constitutional Treaty’.

As a matter of interest and political significance, most member countries decided to ratify the new treaty through their legislatures rather than by hazarding it in a referendum, a decision that caused much discontent in many countries. In the UK, the government declined to have a referendum on the basis of the, not totally convincing, suggestion that the treaty was simply an amendment and a tidying up measure and consequently did not need the confirmation of a referendum in the way necessary and promised for the constitution.

In June 2008 the Irish once again caused a furore in the EU when its electorate voted against the ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon. They were, of course, given a further opportunity to vote on the treaty and, in October 2009, following a number of concessions relating to taxation, ‘family’ issues, such as abortion, euthanasia and gay marriage and the traditional Irish state neutrality, approved it. Following the second Irish vote Poland’s President, Lech Kaczynski, signed the treaty and that only left one member to fully ratify the treaty, the Czech republic. However, following the agreement that the Czechs could have the same protocol seven protections as the UK and Poland, President Vaclav Klaus signed the treaty, the Czech constitutional court dismissed an appeal against the treaty and the EU had a new treaty. It merely remained for the treaty to be put into effect. The necessary alterations to the fundamental treaties governing the EU, brought about by the Lisbon Treaty, were published at the end of March 2010 in the form of an updated Treaty on European Union (TEU), a newly named Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) (formerly the Treaty Establishing the European Community), together with the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CFREU).

Tables of Equivalences, indicating where the provisions of previous iterations of the treaties are now located can be found at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2010:083:0361:0388:EN:PDF

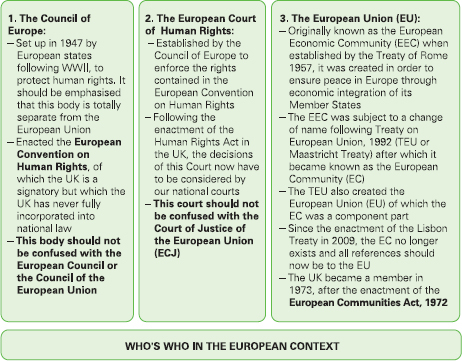

FIGURE 15.1 Who’s Who in the European Context.

The Treaty on European Union (TEU)

The text of the treaty is divided into six parts as follows, with reference to some of the most important specific provisions:

1 Common Provisions

• Article 1 of this treaty makes it clear that ‘The Union shall be founded on the present Treaty and on the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (hereinafter referred to as “the Treaties”). Those two Treaties shall have the same legal value. The Union shall replace and succeed the European Community’. This provision means that the previous confusion between when it was more appropriate to refer to EC rather than the EU has been removed and that it is now correct under all circumstances to refer to the EU. Article 47 provides further that the EU has legal personality, which means that the EU, as well as its constituent members, will be able to be a full member of the Council of Europe. As yet, the EU has not joined the Council, although an agreement to do so was established in July 2011.

• Article 2 establishes that the EU is ‘founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities’.

• Article 3 then states the aims of the EU in very general terms as follows:

° the promotion of peace, its values and the well-being of its peoples;

° the assurance of freedom of movement of persons without internal frontiers but with controlled external borders;

° the creation of an internal market … aiming at full employment and social progress, and a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment;

° the establishment of an economic and monetary union whose currency is the euro; the promotion of its values, while contributing to the eradication of poverty and observing human rights and respecting the charter of the United Nations;

° the sixth aim requires that the EU pursue its objectives by ‘appropriate means’.

• Article 6 binds the EU to the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union and the European Convention on Human Rights.

2 Provisions on democratic principles

• Article 9 establishes the equality of EU citizens and that every national of a member state shall be a citizen of the Union. It makes clear that citizenship of the Union is additional to and does not replace national citizenship.

3 Provisions on the institutions

• Article 13 establishes the institutions in the following order and under the following names (except for the ECB these will be considered in detail below):

° the European Parliament;

° the European Council;

° the Council;

° the European Commission;

° the Court of Justice of the European Union;

° the European Central Bank;

° the Court of Auditors.

• Article 15 establishes the President of the European Council.

• Articles 15(2) and 18 establish the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy to conduct the Union’s common foreign and security policy.

4 Provisions on enhanced cooperations

• Article 20 allows a number of member states to co-operate in furthering integration in a particular area where other members are blocking full integration.

5 General provisions on the Union’s external action and specific provisions on the Common Foreign and Security Policy

Articles 21–46 relate to the establishment and operation of a common EU foreign policy including:

• compliance with the UN charter, promoting global trade, humanitarian support and global governance;

• establishment of the European External Action Service, which will function as the EU’s foreign ministry and diplomatic service;

• the furtherance of military cooperation including mutual defence.

6 Final provisions

• Article 47 establishes the legal personality of the EU.

• Article 48 deals with the method of treaty amendment; either through the ordinary or the simplified revision procedures.

• Articles 49 and 50 deal with applications to join the EU and withdrawal from it.

The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)

This document, going back through several iterations to the original Treaty of Rome, contains the detail of the structure and operation of the European Union. (Once again it should be noted that a table of equivalences/destinations of previous provisions is available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2010:083:0361:0388:EN:PDF.)

Article 2 of this treaty provides that:

When the Treaties confer on the Union exclusive competence in a specific area, only the Union may legislate and adopt legally binding acts, the Member States being able to do so themselves only if so empowered by the Union or for the implementation of Union acts.

Article 3 specifies that the Union shall have exclusive competence in the following areas:

(a) customs union;

(b) the establishing of the competition rules necessary for the functioning of the internal market;

(c) monetary policy for the Member States whose currency is the euro;

(d) the conservation of marine biological resources under the common fisheries policy;

(e) common commercial policy.

Article 3 provides that the Union shall also have exclusive competence for the conclusion of an international agreement when its conclusion is provided for in a legislative act of the Union or is necessary to enable the Union to exercise its internal competence, or in so far as its conclusion may affect common rules or alter their scope.

The provision of specific articles will be considered below.

The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CFREU)

The Charter contains 54 articles divided into seven titles. The first six titles deal with substantive rights relating to:

• dignity, including the right to life and the prohibition of torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment;

• freedom, including the right to liberty and security of person, the right to engage in work and the freedom to conduct a business;

• equality, including equality before the law, and the right not to be discriminated against;

• solidarity, which emphasises workers’ rights to fair working conditions, protection against unjustified dismissal, information and consultation within the undertaking, together with the right to engage in collective bargaining and to engage in industrial action;

• citizens’ rights, including the right to vote and to stand as a candidate at elections; and finally

• justice, which includes the rights to a fair trial, the presumption of innocence, and the right of defence.

The last title, Articles 51–54, deals with the interpretation and application of the Charter.

Many member states, including the UK, have negotiated opt outs of some of the provisions of the charter.

15.1.1 PARLIAMENTARY SOVEREIGNTY, EUROPEAN UNION LAW AND THE COURTS

The doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty has already been considered with respect to the relationship between Parliament and the courts (see 2.3.2, above), and similar issues arise with regard to the relationship between EU law and domestic legislation. It has already been seen that the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty is one of the cornerstones of the UK constitution. One aspect of the doctrine is that, as long as the appropriate procedures are followed, parliament is free to make such law as it determines. The corollary of that is that no current parliament can bind the discretion of a later parliament to make law as it wishes. The role of the court, as also has been seen, is merely to interpret the law made by parliament. Each of these constitutional principles is revealed as problematic in relation to the UK’s membership of the EU and the relationship of domestic and EU law.

Before the UK joined the EU, its law was just as foreign as law made under any other jurisdiction. On joining the EU, however, the UK and its citizens accepted, and became subject to, EU law. This subjection to European law remains the case even where the parties to any transaction are themselves both UK subjects. In other words, in areas where it is applicable, European law supersedes any existing UK law to the contrary. The European Communities Act (ECA) 1972 gave legal effect to the UK’s membership of the EEC, and its subjection to all existing and future Community/Union law was expressly stated in s 2(1), which provides:

All such rights, powers, liabilities, obligations and restrictions from time to time created or arising by or under the Treaties, and all such remedies and procedures from time to time provided for by or under the Treaties, as in accordance with the Treaties are without further enactment to be given legal effect or used in the UK shall be recognised and available in law, and be enforced, allowed and followed accordingly [emphasis added].

Such statutory provision merely reflected the approach already adopted by the CJEU:

By contrast with ordinary international treaties, the EC Treaty has created its own legal system which … became an integral part of the legal systems of the Member States and which their courts are bound to apply [Costa v ENEL (1964)].

The impact of Community/Union law on, and its superiority to, domestic law was clearly stated by Lord Denning MR thus:

If on close investigation it should appear that our legislation is deficient or is inconsistent with Community law by some oversight of our draftsmen then it is our bounden duty to give priority to Community law. Such is the result of s 2(1) and (4) of the European Communities Act 1972 [Macarthys Ltd v Smith (1979)].

Thoburn v Sunderland CC (2002) appeared a simple enough case, but it raised some fundamental constitutional issues. It concerned a Sunderland greengrocer who sold fruit only by imperial weight. He was given a conditional discharge after his conviction under an Order in Council implementing a European Directive. He appealed by way of case stated, arguing that the Weights and Measures Act 1985 took precedence over European law or Orders in Council. His appeal failed, but in deciding the issue, Laws LJ rejected the argument that the overriding force of European law in the UK depends on its own principles as enunciated by the European Court in Costa v ENEL. Laws LJ stated that EU law could not entrench itself, because when Parliament enacted the ECA in 1972, it could not and did not bind subsequent Parliaments. The British Parliament, being sovereign, could not abandon its sovereignty, and there are no circumstances in which the jurisprudence of the Court of Justice could elevate Community law to a status within the corpus of English domestic law to which it could not aspire by any route of English law itself.

However, he went on, the traditional doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty has been modified by the common law, which has in recent years created classes of legislation that cannot be repealed by mere implication, that is, without express words to that effect. There now exists a clear hierarchy of Acts of Parliament – ‘ordinary’ statutes, which may be impliedly repealed, and ‘constitutional’ statutes, clearly including the ECA, which may not. The ECA is a constitutional statute and cannot be impliedly repealed, but that truth derives not from EU law but from the common law. In summary, the appropriate analysis of the relationship between EU and domestic law required regard to four propositions:

(i) Each specific right and obligation provided under EC/EU law was, by virtue of the 1972 Act, incorporated into domestic law and took precedence. Anything within domestic law which was inconsistent with EC/EU law was either abrogated or had to be modified so as to avoid inconsistency.

(ii) The common law recognised a category of constitutional statutes.

(iii) The 1972 Act was a constitutional statute which could not be impliedly repealed.

(iv) The fundamental legal basis of the UK’s relationship with the EU rested with domestic rather than European legal powers.

Thus did Laws LJ maintain balance between the supremacy of EU law in matters of substantive law, and the supremacy of the UK Parliament in establishing the legal framework within which EU law operates. Clause 18 of the European Union Bill 2010/11 provides a statutory confirmation of Laws’ reasoning.

An example of EU law invalidating the operation of UK legislation can be found in the Factortame cases. The Common Fishing Policy established by the EEC had placed limits on the amount of fish that any Member country’s fishing fleet was permitted to catch. In order to gain access to British fish stocks and quotas, Spanish fishing boat owners formed British companies and reregistered their boats as British. In order to prevent what it saw as an abuse and an encroachment on the rights of indigenous fishermen, the British government introduced the Merchant Shipping Act 1988, which provided that any fishing company seeking to register as British would have to have its principal place of business in the UK and at least 75 per cent of its shareholders would have to be British nationals. This effectively debarred the Spanish boats from taking up any of the British fishing quota. Some 95 Spanish boat owners applied to the British courts for judicial review of the Merchant Shipping Act 1988 on the basis that it was contrary to Community law.

The High Court decided to refer the question of the legality of the legislation to the ECJ under Article 267 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) (formerly Art 234 and Art 177 of previous versions of the treaty (see 15.3.6 below), but in the meantime granted interim relief, in the form of an injunction disapplying the operation of the legislation to the fishermen. On appeal, the Court of Appeal removed the injunction, a decision that was confirmed by the House of Lords. However, the House of Lords referred the question of the relationship of Community law and contrary domestic law to the ECJ. Effectively, they were asking whether the domestic courts should follow the domestic law or Community law. The ECJ ruled that the Treaty of Rome required domestic courts to give effect to the directly enforceable provisions of Community law and, in doing so, such courts are required to ignore any national law that runs counter to Community law. The House of Lords then renewed the interim injunction. The ECJ later ruled that in relation to the original referral from the High Court, the Merchant Shipping Act 1988 was contrary to Community law and therefore the Spanish fishing companies should be able to sue for compensation in the UK courts. The subsequent claims also went all the way to the House of Lords before it was finally settled in October 2000 that the UK was liable to pay compensation, which was estimated at between £50 million and £100 million.

The foregoing has demonstrated the way in which, and the extent to which, the fundamental constitutional principles of the UK are altered by its membership of the EU. Both the sovereign power of Parliament to legislate in any way it wishes and the role of the courts in interpreting and applying such legislation are now circumscribed by EU law. There remains one hypothetical question to consider and that relates to the power of Parliament to disapply legislation from the EU. While ECJ jurisprudence might not recognise such a power, it is certain that the UK Parliament retains such a power in UK law. If EU law receives its superiority as the expression of Parliament’s will in the form of s 2 of the European Communities Act, as suggested by Lord Denning in Macarthys, it would remain open to a later Parliament to remove that recognition by passing new legislation. Such a point was actually made by the former Master of the Rolls in his judgment in that very case:

If the time should come when our Parliament deliberately passes an Act with the intention of repudiating the Treaty or any provision in it or intentionally of acting inconsistently with it and says so in express terms then I should have thought that it would be the duty of our courts to follow the statute of our Parliament.

Article 10 (formerly 5) requires:

Member States to take all appropriate measures, whether general or particular, to ensure fulfilment of the obligations arising out of this Treaty or resulting from action taken by the institutions of the Community. They shall facilitate the achievement of the Community’s tasks. They shall abstain from any measure which could jeopardise the attainment of the objectives of this Treaty.

This Article effectively means that UK courts are now EU law courts and must be bound by, and give effect to, that law where it is operative. The reasons for the national courts acting in this manner were considered by John Temple Lang, Director in the Competition Directorate General, in an article entitled ‘Duties of national courts under Community constitutional law’ [1997] EL Rev 22. As he wrote:

National courts are needed to give companies and individuals remedies which are as prompt, as complete and as immediate as the combined legal system of the Community and of Member States can provide. Only national courts can give injunctions against private parties for breach of Community law rules on, for example, equal pay for men and women, or on restrictive practices. Private parties have no standing to claim injunctions in the Court of Justice against a Member State; they can do so only in a national court. In other words, only a national court could give remedies to individuals and companies for breach of Community law which are as effective as the remedies for breach of national law.

European Union Act 2011

As was stated in Chapter 2, in September 2011 Parliament passed the European Union Act 2011. The main purpose of the Act was to make provision for the application of the post-Lisbon treaties. However, the Act also amended the European Communities Act (ECA) 1972 to ensure that any proposed future EU treaty, or amendment to the treaties, which purport to transfer competences or areas of power from the UK to the EU will have to be subject to a domestic referendum. Section 18 of the Act, for the first time, places the common law principle of parliamentary sovereignty on a statutory footing and states that all EU law takes effect in the UK only by virtue of the will of Parliament, as provided in the ECA 1972. Such measures were taken in an endeavour to provide clear statutory authority for the superiority of domestic law over EU law and to circumscribe any suggestion that EU law constitutes a new higher autonomous legal order in its own right. It has been suggested that these measures were a sop to the Eurosceptic wing of the Conservative Party within the coalition government and their precise effect remains to be seen.

15.2 SOURCES OF EUROPEAN UNION LAW

Community law, depending on its nature and source, may have direct effect on the domestic laws of its various members; that is, it may be open to individuals to rely on it without the need for their particular State to have enacted the law within its own legal system (see Factortame).

There are two types of direct effect. Vertical direct effect means that the individual can rely on EU law in any action in relation to their government, but cannot use it against other individuals. Horizontal direct effect allows the individual to use the EU provision in an action against other individuals. Other EU provisions only take effect when they have been specifically enacted within the various legal systems within the Community.

The sources of Community law are fourfold:

• internal treaties and protocols;

• international agreements;

• secondary legislation;

• decisions of the CJEU.

15.2.1 INTERNAL TREATIES

Internal treaties govern the Member States of the EU, and anything contained therein supersedes domestic legal provisions. Upon its joining the then Community, the Treaty of Rome was incorporated into UK law by the ECA 1972. Since that date the UK has been subject to the various iterations of the ruling treaties. As was considered previously, the ruling treaties are now:

• Treaty on European Union (TEU);

• Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU);

• Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.

As long as treaties are of a mandatory nature and are stated with sufficient clarity and precision, then they have both vertical and horizontal effect (Van Gend en Loos (1963)).

15.2.2 INTERNATIONAL TREATIES

International treaties are negotiated with other nations by the European Commission on behalf of the EU as a whole and are binding on the individual members of the EU.

15.2.3 SECONDARY LEGISLATION

Secondary legislation is provided for under Art 249 (formerly 189) of the Treaty of Rome. It provides for three types of legislation to be introduced by the European Council and Commission:

• Regulations apply to, and within, Member States generally, without the need for those States to pass their own legislation. They are binding and enforceable from the time of their creation and individual States do not have to pass any legislation to give effect to regulations. Thus, in Macarthys Ltd v Smith (1979), on a referral from the Court of Appeal to the ECJ, it was held that Art 157 (formerly 141) entitled the plaintiff to assert rights that were not available to her under national legislation, the Equal Pay Act 1970, that had been enacted before the UK had joined the EEC. Whereas the national legislation clearly did not include a comparison between former and present employees, Art 157’s reference to ‘equal pay for equal work’ did encompass such a situation. Smith was consequently entitled to receive a similar level of remuneration to that of the former male employee who had done her job previously. The horizontal direct effect of regulations was confirmed by the ECJ in Munoz y Cia SA v Frumar Ltd (2002), in which it was held that the claimant was entitled to bring a civil claim against the defendant for failure to comply with EU labelling regulations.

Regulations must be published in the Official Journal of the EU. The decision as to whether or not a law should be enacted in the form of a regulation is usually left to the Commission, but there are areas where the Treaty of Rome requires that the regulation form must be used. These areas relate to: the rights of workers to remain in Member States of which they are not nationals; the provision of State aid to particular indigenous undertakings or industries; the regulation of EU accounts and budgetary procedures.

• Directives, on the other hand, state general goals and leave the precise implementation in the appropriate form to the individual Member States. Directives, however, tend to state the means as well as the ends to which they are aimed and the CJEU will give direct effect to directives that are sufficiently clear and complete. See Van Duyn v Home Office (1974). Directives usually provide Member States with a time limit within which they are required to implement the provision within their own national laws. If they fail to do so, or implement the directive incompletely, then individuals may be able to cite and rely on the directive in their dealings with the State in question. Further, Francovich v Italy (1991) has established that individuals who have suffered as a consequence of a Member State’s failure to implement Community law may seek damages against that State.

• Decisions on the operation of European laws and policies are not intended to have general effect but are aimed at particular States or individuals. They have the force of law under Art 288 (formerly 249).

• Additionally, Art 17(1) TEU (formerly 211 TEC) provides scope for the Commission to issue recommendations and opinions