The Enforcement of Laws and the Collection, Preservation, and Interpretation of Evidence

6

The Enforcement of Laws and the Collection, Preservation, and Interpretation of Evidence

Chapter outline

Introduction: Private Security’s Role in Enforcing the Law

Classification of Criminal Offenses and Related Penalties

Specific Types of Crimes and Offenses

Kidnapping and False Imprisonment

Offenses against the Habitation and Other Buildings

Offenses against Public Order and Decency

The Admission of Business Records

Real and Demonstrative Evidence

Practical Exercise: Cross-Examination

A. Potpourri of Evidentiary Principles

Introduction: Private Security’s Role in Enforcing the Law

Private security is an indispensable cog in the American machinery of justice. Previous commentary outlines the Herculean contributions made by the industry in the protection of social and economic order. Even private security’s harshest, most strident critics realize that without the services of private security, a gaping, colossal protection vacuum would exist in the distribution of justice, the protection of assets and facilities, and related services. Public policing alone simply cannot fend off the escalating criminality or solely assure the integrity of community and governmental infrastructures. It is common knowledge that the security industry performs numerous functions, from crowd control to physical perimeter protection in public and private installations, and deterrent and preventive activities regarding shoplifting and other corporate crime. But precisely which laws, statutes, or specific violations cover these sorts of activities? Does it make imminent sense that private security operatives have training and foundational knowledge in the law of crimes as well as the underlying proof requirements? And if the industry is to make a meaningful contribution in the apprehension and subsequent prosecution of criminal behavior, must its agents know and understand the evidentiary demands for a successful prosecution? Surely any professional security force will need to comprehend the definitions of criminal behavior and the evidentiary proof that must accompany any attempt to successfully conclude a criminal investigation and prosecution. These are the chief aims of the chapter.

Defining Criminal Liability

Before private security operatives can intelligently detect or enforce criminal behavior, they must master the essential elements of the alleged criminal behavior. More particularly, the industry must focus on the crimes more likely encountered by its field personnel.

Every crime consists of two basic elements:

Taking these elements into consideration, guilt under nearly all criminal offenses calls for proof of both the act itself and the mind that triggers, intends, or prompts the act. In the mental faculty requirement, the actor must do more than merely act, but contemplate upon the act before its commission and present some sort of mental intentionality. One without the other is bound to lead to failure in the American conception of criminal culpability.

In some intellectual circles there is a third element—namely, causation, which demands proof that the act and the mind together, working in consort, lead to a particular consequence. While not necessarily central to every criminal advocacy, it is wise to consider the question of whether a criminal’s mind prompted a particular act that in turn caused a particular harm or injury. This is a thumbnail sketch of the criminal definition.

The Criminal Act (Actus Reus)

Not unexpectedly, criminal liability cannot attach without a deed, an act, an offense, or an omission of specifically enumerated conduct. Crimes are not inventions or fantasies but real human activity. Merely thinking about crimes, with rare exceptions, is not criminally punishable. Thoughts, no matter how bizarre or perverted, are not punishable unless put into effect. Thus, in order to be found guilty of theft, an individual has to take overt steps toward the unlawful taking of another’s property. He or she may think obsessively about the desire to be in possession of some object, but until some overt act or course of conduct is chosen and put into effect, there is no actus reus.1 Hence, every criminal construction insists on an act of some sort.

A criminal act must be a voluntary act. The law does not hold accountable those individuals who are mentally incapacitated or operating against their will, by either duress or coercion, or suffering from a related or corollary disease or mental defect that substantially impacts the mental faculty.2 The American Law Institute’s Model Penal Code, in its proposed 1962 draft, defines the nature of a voluntary act for criminal liability purposes:

Requirement of Voluntary Act; Admission as Basis of Liability; Possession Is an Act.

Criminal liability does not attach unless the prosecution can demonstrate an act that is voluntary and not the result of unintentional, accidental, or nonvolitional circumstances. Acts by omission—that is, a failure to act when the law so dictates, such as the case of a parent who neglects his child or fails to save the child when in peril—are also within the definition of actus reus.4 In this sense, acts fall into two categories: commission and omission.

For a fascinating report on how federal codes are eroding the requirements of a mental state, read the Heritage Foundation’s report at http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2010/05/the-criminal-intent-report-congress-is-eroding-the-mens-rea-requirement-in-federal-criminal-law.

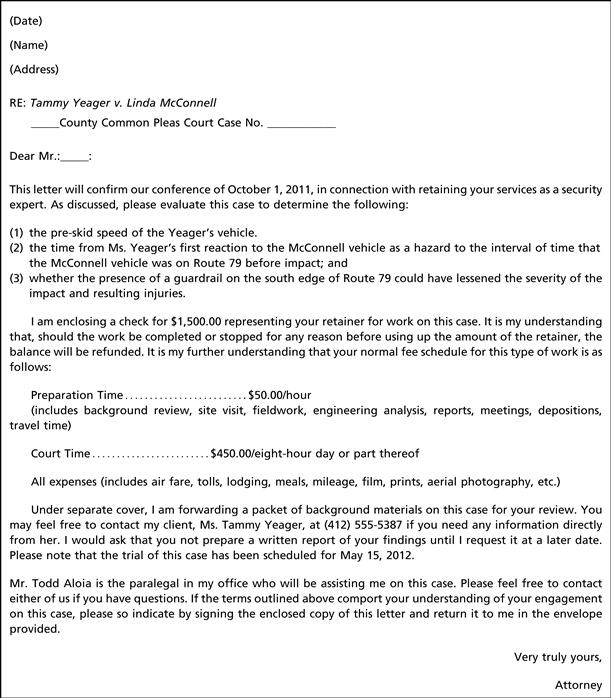

An incident report form, like Figure 6.1,5 aids the security investigator in determining the nature of the act.

Figure 6.1 Incident Report.

The Criminal Mind (Mens Rea)

Determining the state of one’s mind, the mens rea, is a much more complicated exercise than the proof of a criminal act. It has long been a major tenet of American jurisprudence that persons not in control of their mind or fully functional in mental state are less likely to be criminally responsible. Subjectively or objectively appraising what is in a person’s mind can be gleaned from the facts themselves, the corpus delicti, the statements and comments of the actor by oral or written form, as well as psychological and psychiatric evidence. All of these conclusions must be linked to the crime in question. While most scholars and academics concede that there is such a thing as mens rea, it is, nevertheless, very subjective and difficult to prove.6 That a defendant may intend the general consequences of a certain action is clear, but how intensely the person actually desires to cause harm and the actual injury level the individual intends is harder to quantify.

Consider the various descriptive adjectives and adverbs that are utilized to describe a person’s state of mind:

Admittedly, these terms can never fully describe the actor’s mind, but at best they imply the conduct’s level of intentionality. Mens rea codifications attempt to categorize malefactors and their respective mental states, although this is an imperfect exercise.

Evaluate the Power Point presentation from the University of North Texas at http://pacs.unt.edu/criminal-justice/Course_Pages/CJUS_2100/2100chapter2.ppt#329,10,Slide 10.

Diverse descriptive states of culpability have been encompassed in the Model Penal Code. Some portions are reproduced as follows:

General Requirements of Culpability

(2) Kinds of Culpability Defined.

(a) Purposely.

A person acts purposely with respect to a material element of an offense when:

(b) Knowingly.

A person acts knowingly with respect to a material element of an offense when:

(c) Recklessly.

(d) Negligently.

A person acts negligently with respect to a material element of an offense when he should be aware of a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the material element exists or will result from his conduct.8

Security professionals should be vigilant in their assessment of facts and conditions at a crime scene because conduct can be explained in more than one way. Instead of always assuming a crime occurred, look for secondary explanations, such as mistake of fact or law regarding a right to property; inadvertent entry rather than an unlawful trespass; or an act of self-defense rather than an offensive touching. Security investigators and officers must not assume that the act is coupled with a criminal mind. Neither the act nor the mind alone will suffice since “criminal liability is predicated upon a union of act and intent or criminal negligence.”9

Classification of Criminal Offenses and Related Penalties

Common law and statutory guidelines also characterize criminal behavior into various classifications or types. Those classifications generally include the following:

The security industry’s concern will be the detection and apprehension of misdemeanants and felons whose crimes constitute the basic menu of criminal charges including assault, battery, theft and related property offenses, sexual offenses, intimidation and harassment, and white-collar crime including forgery, credit card fraud, and the like. Treason and other infamous crimes emerge in cases of international terrorism and homeland security, and given the rising influence of private sector justice in the global war on terror, they should give rise to more involvement. The entire airspace industry is dependent on personnel not only trained in security issues but also the criminal law issues that surround breaches of security at airport facilities. Shoplifting and retail theft may be designated a “summary” offense. Summary offenses generally consist of public order violations, including failure to pay parking tickets, creating a temporary obstruction in a public place, public intoxication, or other offenses of a less serious nature that are rarely punishable by a term of imprisonment14 but are regularly witnessed by the security professional, like lower-level shoplifting.

At common law, the designation of an act as a felony constituted an extremely serious offense. Penal and correctional response to felony behavior included the death penalty and forfeiture of all lands, goods, and other personal property. Generally, a felony was any capital offense, namely, murder, manslaughter, rape, sodomy, robbery, larceny, arson, burglary, mayhem, and other violent conduct.15 An alternative way of defining a felony was the severity of its corresponding punishment. Felony was defined “to mean offenses for which the offender, on conviction, may be punished by death or imprisonment in the state prison or penitentiary; but in the absence of such statute the word is used to designate such serious offenses as were formally punishable by death, or by forfeiture of the lands or goods of the offender.”16 In other words, a crime could be a felony or a misdemeanor not because of its severity or subsequent impact but because of the term of incarceration. Modern criminal analysis shows confused and perplexing legislative decision making on the nature of a felony and a misdemeanor. The President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, in its Task Force Report on the Courts,17 relates:

A study of the Oregon Penal Code revealed that 1,413 criminal statutes contained a total of 466 different types and lengths of sentences. The absence of legislative attention to the whole range of penalties may also be demonstrated by comparisons between certain offenses. A recent study of the Colorado Statutes disclosed that a person convicted of a first degree murder must serve ten (10) years before becoming eligible for parole, while a person convicted of a lesser degree of the same offense must serve at least fifteen (15) years; destruction of a house with fire is punishable by a maximum twenty (20) years imprisonment, but destruction of a house with explosives carries a ten (10) year maximum. In California, an offender who breaks into an automobile to steal the contents of the glove compartment is subject to a fifteen (15) year maximum sentence but if he stole the car itself, he would face a maximum ten (10) year term.

Although each offense must be defined in a separate statutory provision, the number and variety of sentencing distinctions which result when legislatures prescribe a separate penalty for each offense are among the main causes of the anarchy in sentencing that is so widely deplored.18

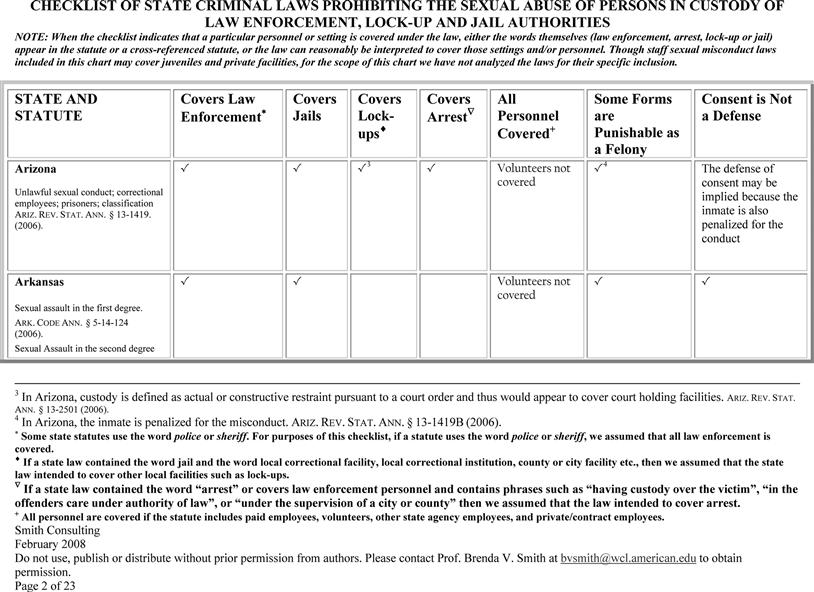

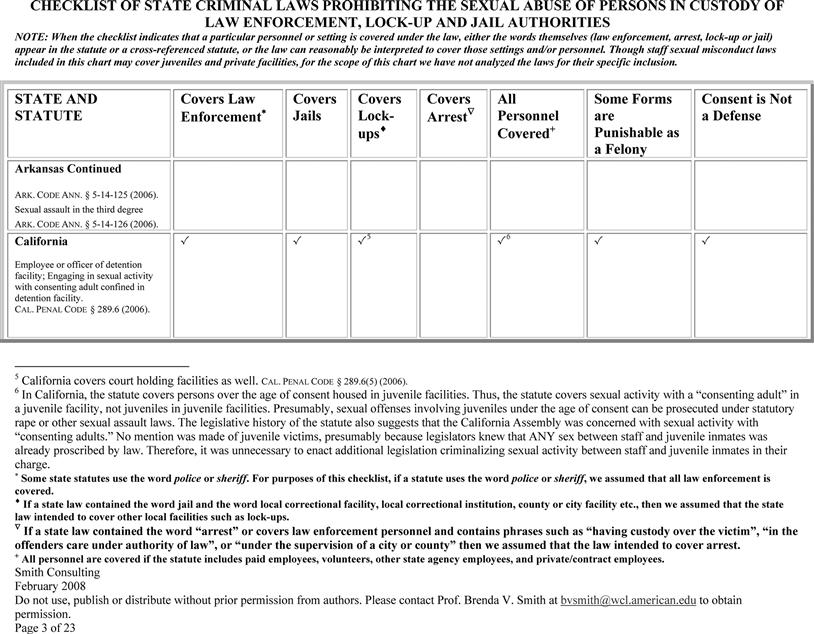

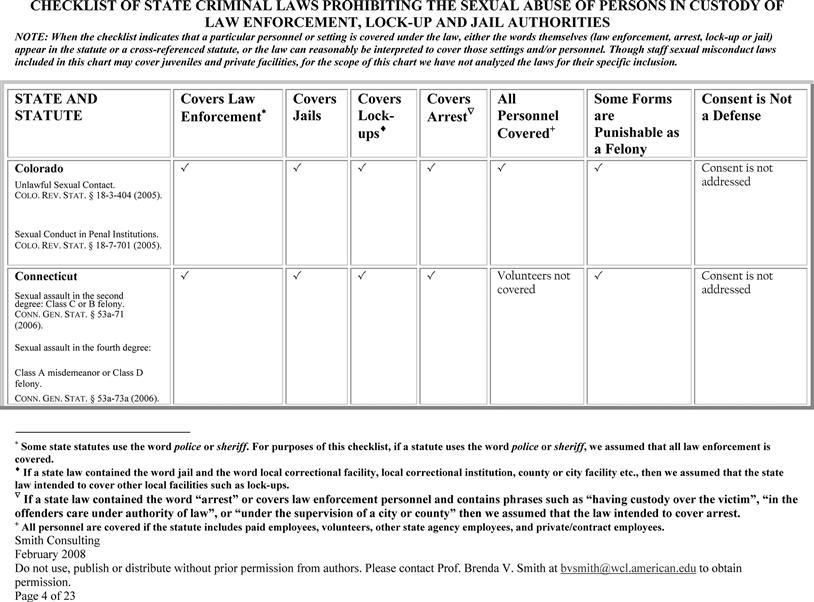

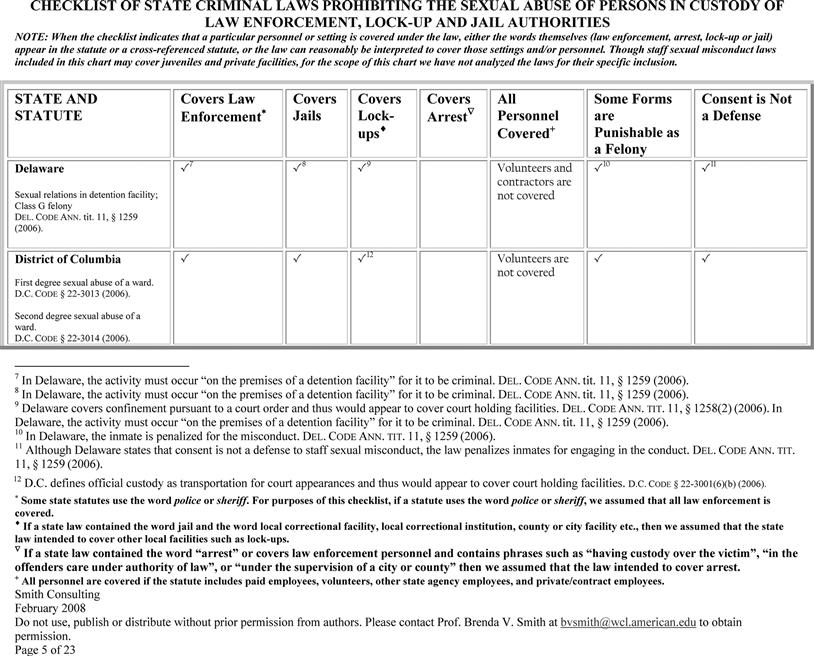

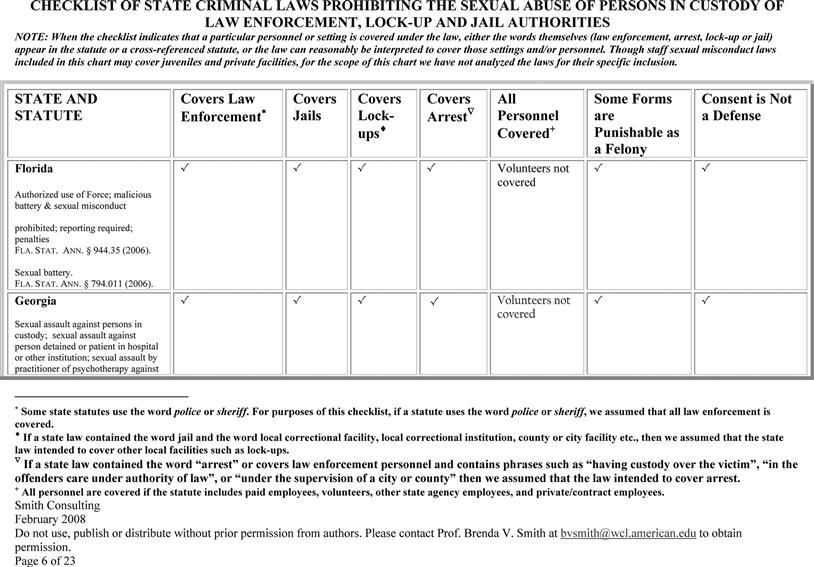

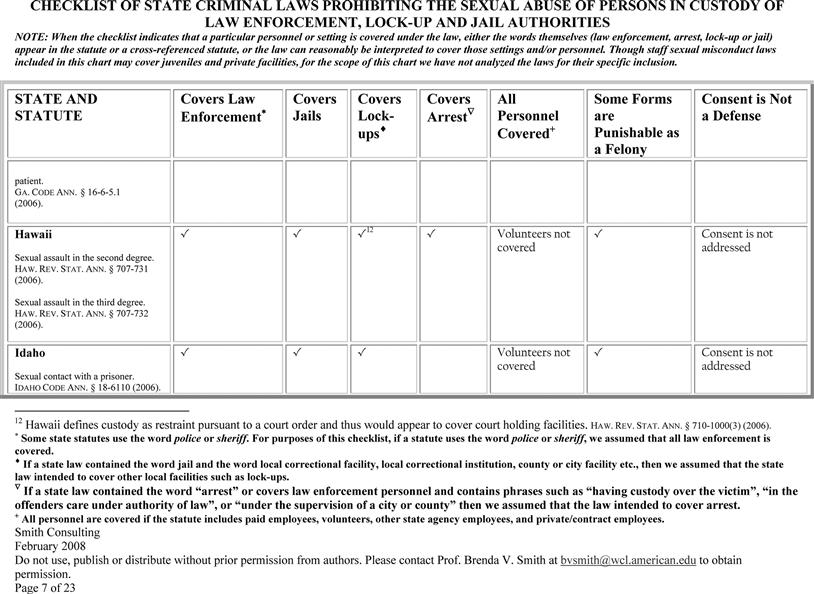

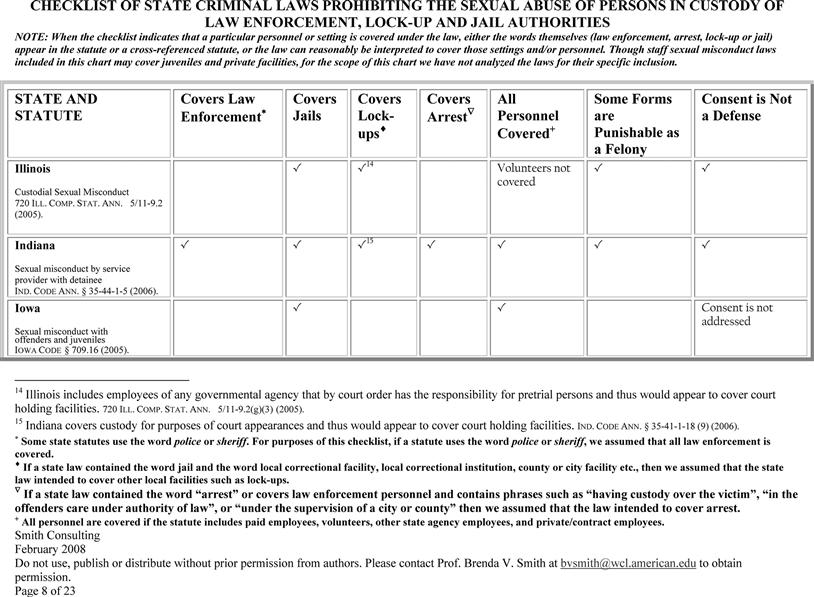

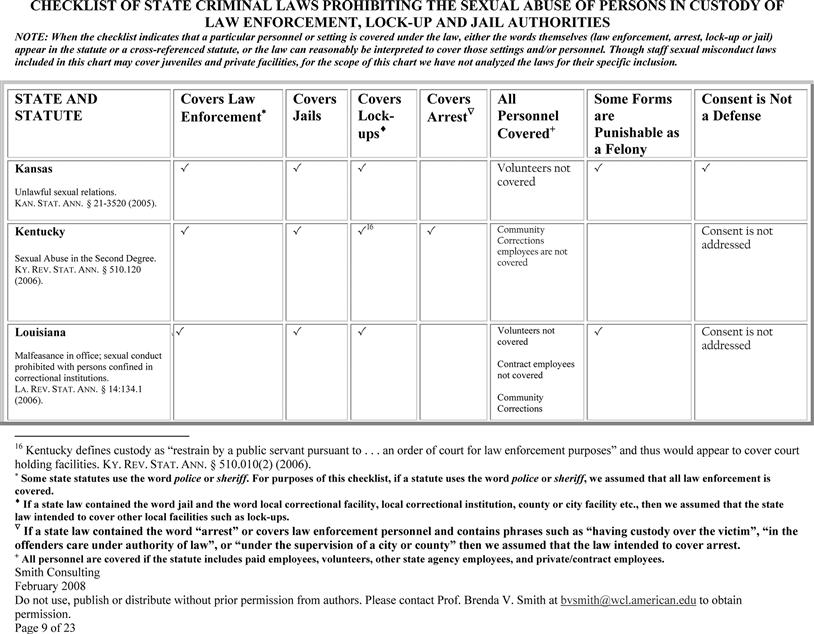

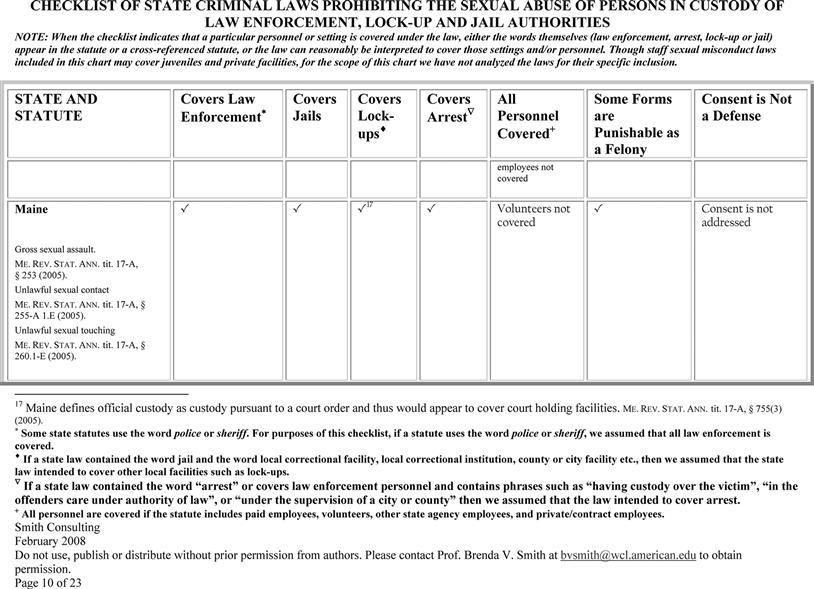

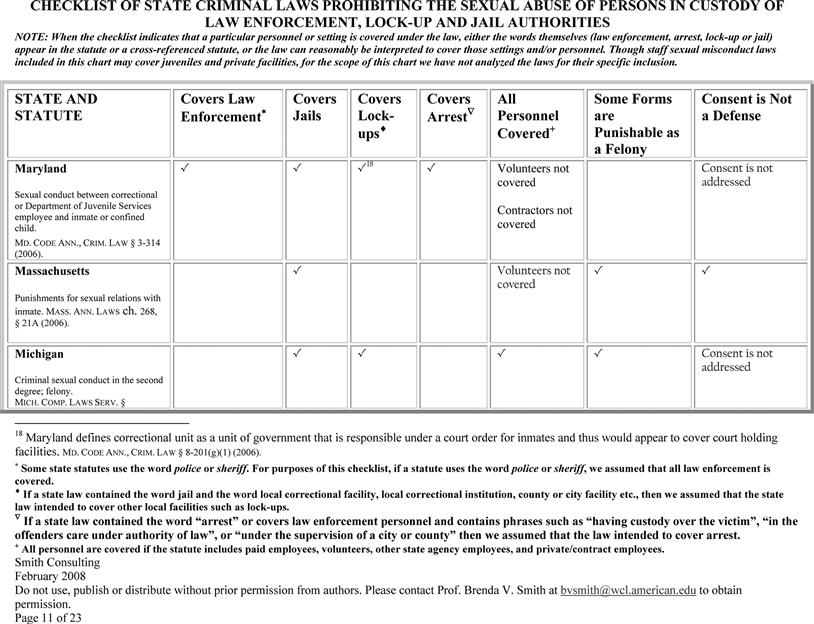

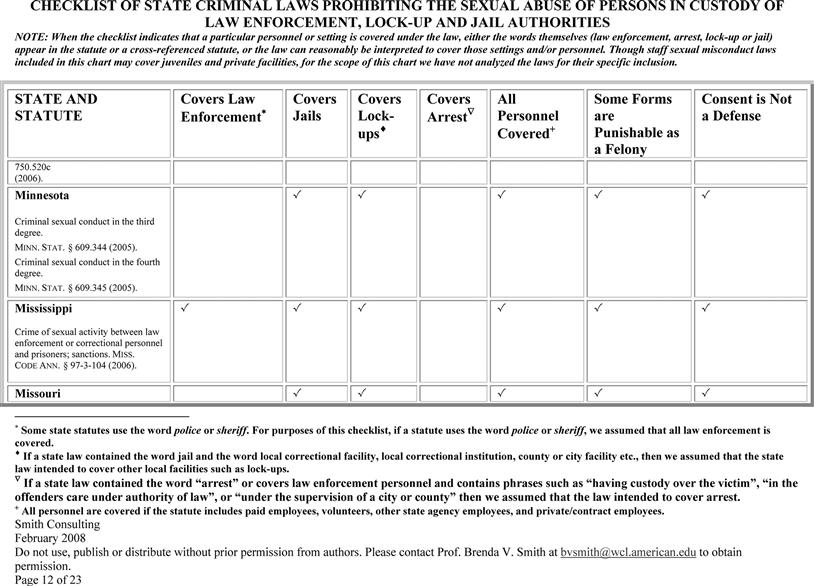

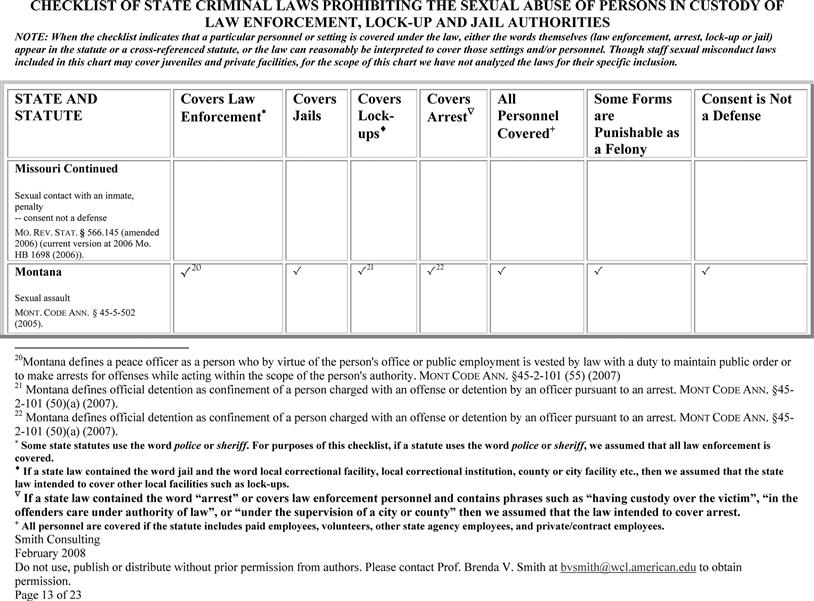

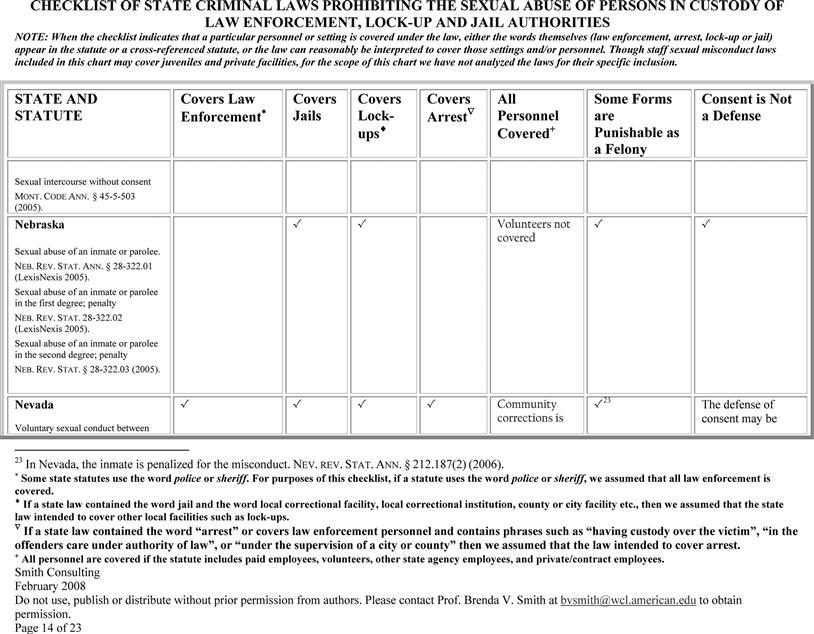

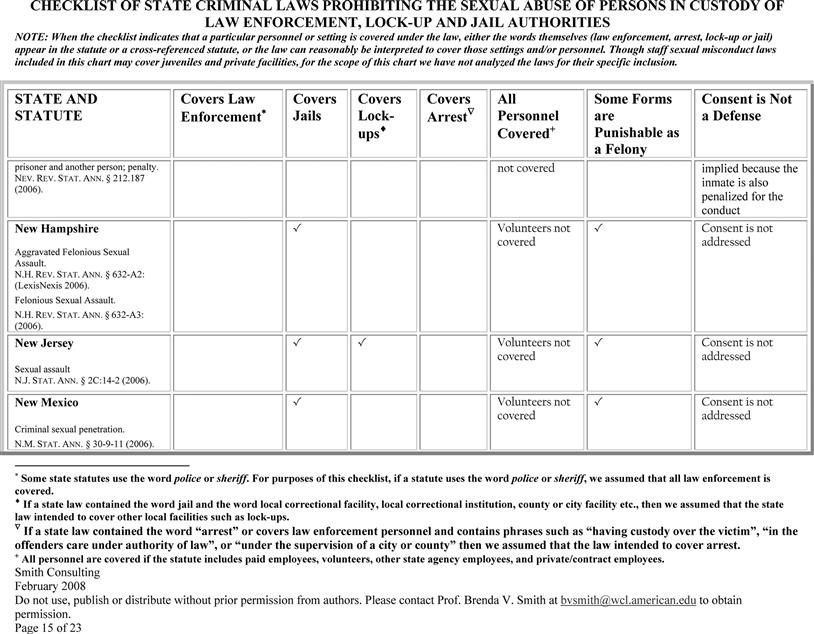

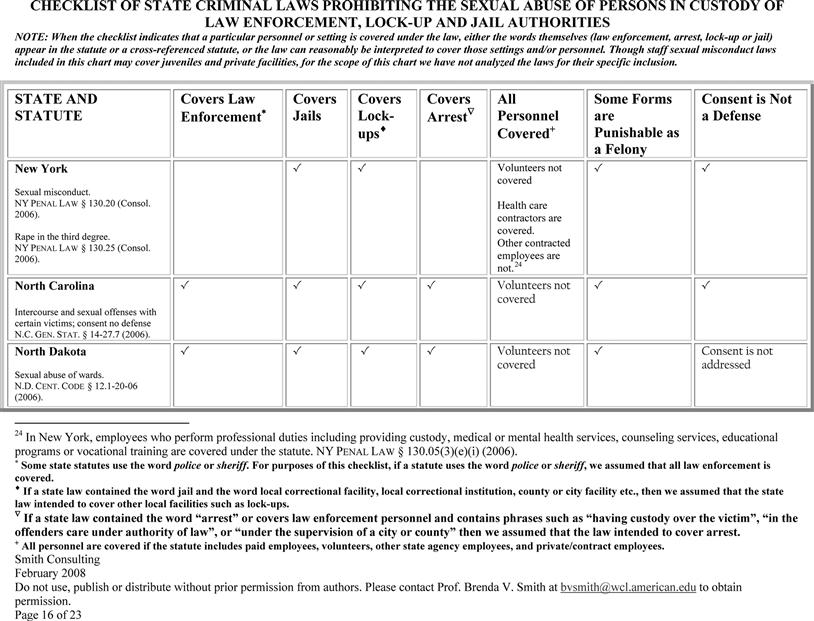

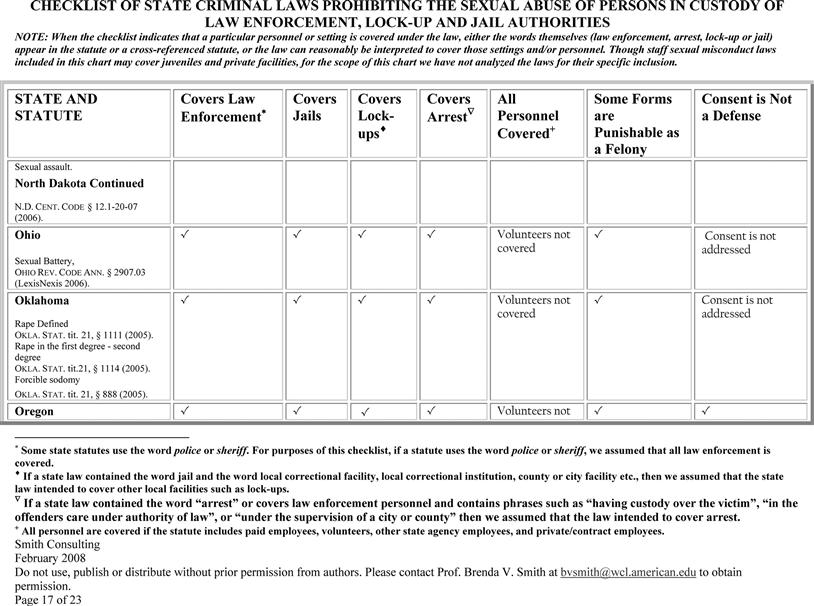

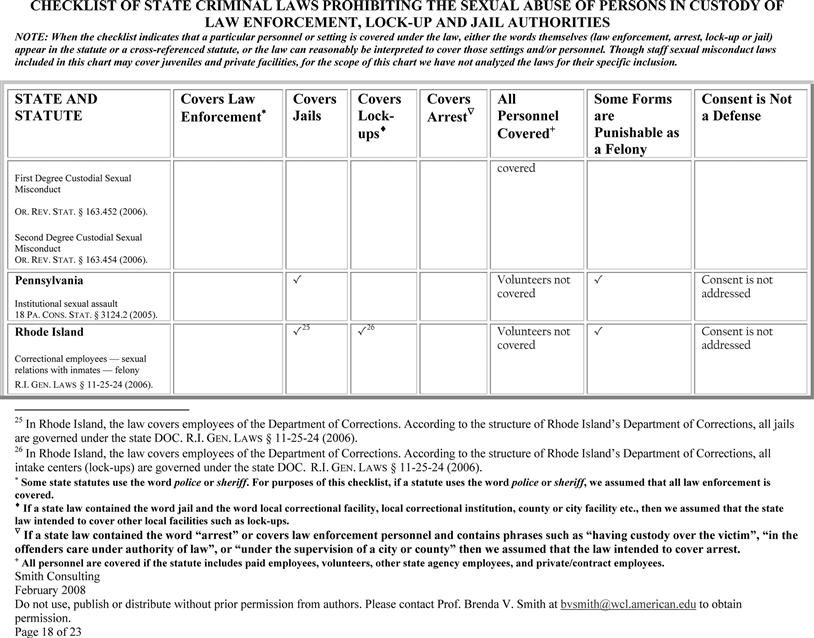

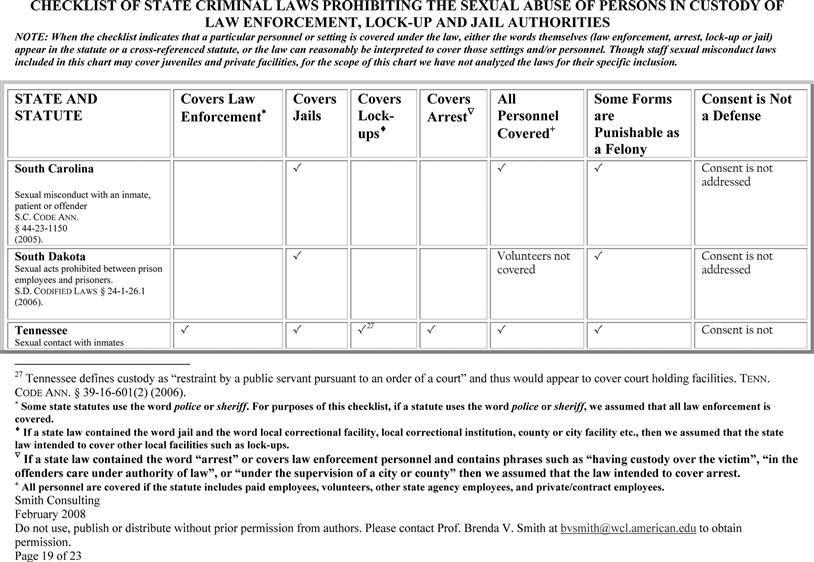

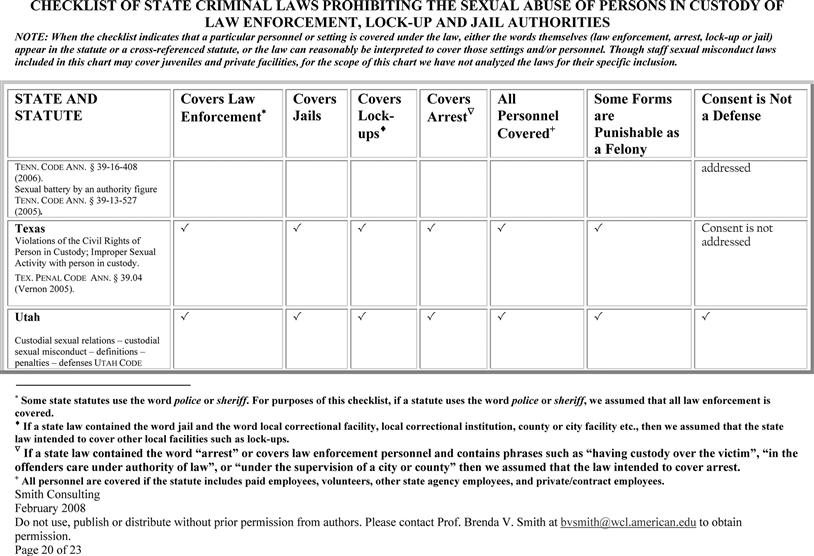

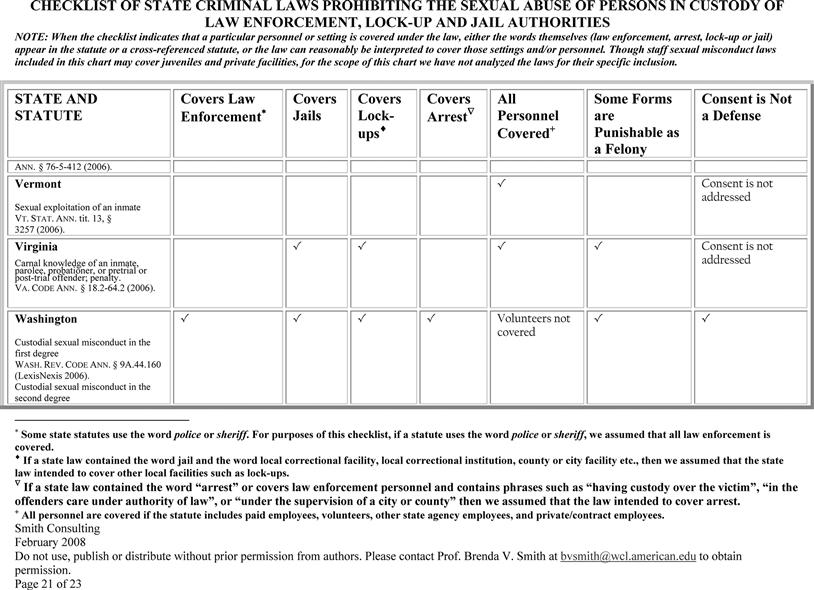

In defining the term “misdemeanor,” legislatures and jurists use a process of elimination holding that an offense not deemed a felony is, deductively, a misdemeanor. Usually misdemeanors are offenses punishable by less than a year’s incarceration. The popular perception that misdemeanors are not serious offenses may be a faulty impression. Criminal codes surprise even the most seasoned justice practitioner, who frequently finds little logic in an offense’s definition, resulting classification, and corresponding punishment. For examples of this confusion, review selected state code provisions on “sexual offenses.”19

Specific Types of Crimes and Offenses

Offenses against the Person

Felonious Homicide

The security industry cannot avoid the ravages of criminal homicide, and in fact, because of the improper use of weaponry or mistaken identity, it is sometimes the accused. Criminal acts of homicide are being recorded because of the installation, maintenance, and operational oversight of electronic surveillance systems and other technological equipment utilized to protect the internal and external premises of businesses. As the public sector continues to transfer and privatize many of its traditionally public police functions, such as in the area of courtroom and prison security, violent acts of homicide are unfortunately replayed. Airport terrorism, failed executive protection programs, and attempted or actual homicides on armored car money carriers are other distressing examples of criminal homicide. This subsection deals only with felonious acts of homicide, and the security professional is reminded that nonculpable homicide occurs in cases of self-defense, necessity in time of war, or by legal right, authority, or privilege.20 Criminal homicide is defined by the Model Penal Code as follows:

The Model Penal Code, after this general legislative introduction, precisely defines each type of homicide.

Murder

A charge of murder will be upheld when,

(a) it is committed purposely or knowingly; or

(b) it is committed recklessly under circumstances manifesting extreme indifference to the value of human life. Such recklessness and indifference are presumed if the actor is engaged or is an accomplice in the commission of, or an attempt to commit, or flight after committing or attempting to commit robbery, rape, deviate sexual intercourse by force or threat of force, arson, burglary, kidnapping or felonious escape.22

The code as suggested requires a high level of mental faculty. While the law of criminal intent varies, most major capital offenses require what is known as specific intent.23 Specific intent can be loosely described as premeditation or a mind possessive of malice aforethought. In other words, the criminal actor wants, desires, wishes, knows, and realizes the ramifications and repercussions of his or her activity. Although the law does not require an intelligent or an esoteric thinker, there is a clear, lucid mindset operating. The level of mind required for a charge of murder was clearly discerned in a Michigan case, People v. Moran:24

Malice aforethought is the intention to kill, actual or implied, under circumstances which do not constitute excuse or justification or mitigate the degree of the offense of manslaughter. The intent to kill may be implied where the actor actually intends to inflict great bodily harm or the natural tendency of his behavior is to cause death or great bodily harm.25

Despite the legal attempts to objectify mental intentions, there will always be subjective underpinnings. The security practitioner must gauge conduct in light of all circumstances. He or she must ask him or herself whether the facts of a given case lead a reasonable person to the conclusion that the person not only knew what he or she was doing but wished both the method and the end result.

Manslaughter

Less crystalline as to intentionality, criminal codifications make room for a mindset that is impacted or effected by mitigation and other external forces. In homicide, the crime that fits this description is manslaughter. Most jurisdictions further grade felonious homicide into another central category: voluntary or involuntary manslaughter.26 While specific intent is always required for a charge of murder, except in cases of strict liability such as cop killing and felonious homicide, actions and conduct that are not as intellectually precise, not as free from influential mitigating factors and provocation, sometimes qualify for a less rigorous mental state, that of general intent.27 This is not to say that some jurisdictions do not have a specific intent requirement for a manslaughter charge, for there are diverse ways of classifying the mind in the law of manslaughter. For the most part, a charge of manslaughter, whether voluntary or involuntary, has a significantly smaller burden of proof regarding the actor’s objective state of mind. This distinct language is readily discoverable in the following statute:

Compared to the murder statute, the language of the voluntary manslaughter provision permits an evaluation of various mitigating circumstances including provocation, intense and emotional passion, and sudden and impetuous events.30 In involuntary cases, the issue of gross negligence is appropriately weighed. In these cases, the court instructs the jury on the negligent nature of the act that causes harm. The defendant need not specifically intend the commission of any crime but could have or should have known the consequences. These are acts, mistaken and accidental in nature, unresponsive to others. Cases of automobile manslaughter or the mishandling of weapons while in a drunken stupor are good examples.31

In security settings, manslaughter is a more common event, particularly since practitioners are often called upon in hostile crowd control situations, in the maintenance of order at special events, and for related activities.

Read and interpret a California vehicular manslaughter law at http://dmv.ca.gov/pubs/vctop/appndxa/penalco/penco191_5.htm.

Felony Murder Rule

Whether the jurisdiction has a felony murder rule (FMR) in operation is another security industry concern since the charge has far-reaching tentacles that pull in all operatives acting in consort with one another. Hence, if a team of four security officers are on a stakeout and one of them unlawfully shoots another, even one of the officers, and lacks the privilege or right to do so, all will be held accountable. One of the officers would have to be engaged in felonious conduct. As outlined in the Code Section 210.1(a) above on criminal homicide, a charge of murder is appropriate when any individual dies during the commission of any major capital felony.32 Co-conspirators, accomplices, or other individuals, even though they did not pull the trigger, plan the murder, or personally wish or desire for the death of another, can be felony murderers. Hence, bank robbers or home invaders committing burglary, causing the death of any party, whether it be responding police, inhabitants, or even the partners in crime, will trigger the FMR.

The felony murder rule has been the subject of severe legal challenges in recent years. “There has been a discernible but not universal trend towards limiting the felony murder doctrine. The trend seems to be related to increasing skepticism as the extent to which the felony murder rule in fact serves a legitimate function or at least as to whether it serves its function or functions at an acceptable cost.”33 The most heated debate occurs when two or more persons are engaged in a theft, robbery, or burglary, obviously less serious offenses than murder or manslaughter, and someone dies by accident or negligence.34 However, the strict liability nature of the felony murder rule forces criminals to think of the possible potential ramifications of their behavior, which surely includes the death of the participants and bystanders, during the commission of a felonious act.35

There are groups and associations solely dedicated to elimination of the Felony Murder Rule. See Felonymurder.org at: http://felonymurder.org.

Assault

Aside from theft actions, security officers witness no other crime as regularly as assault and battery. In Chapter 4, readers were introduced to the concept of assault in a civil sense, although there is a corresponding criminal definition as well. At common law, assault and battery were separate offenses, the former being a threat to touch or harm and the latter being the actual offensive touching. Most jurisdictions have merged the offenses, at least in a criminal context, while still distinguishing the offenses by severity and degree. The Model Penal Code poses the following construction:

(1) Simple Assault. A person is guilty of assault if he:

(a) attempts to cause or purposely, knowingly or recklessly causes bodily injury to another; or

(b) negligently causes bodily injury to another with a deadly weapon; or

(c) attempts by physical menace to put another in fear of imminent serious bodily harm.

(2) Aggravated Assault. A person is guilty of aggravated assault if he:

Most security specialists will encounter the crimes known as assault. Efforts to control crowds, secure buildings and installations, apprehend or detain a disgruntled employee, break up disputants in commercial establishments, and handle unruly and disgruntled shoppers in retail establishments are ripe settings to encounter assailants.

Assault can be an extremely serious offense, particularly under the “aggravated” provision.37 In fact, some jurisdictions have adopted reckless endangerment,38 a new statutory design that describes even more severe conduct. See the following example:

The risk must be of such a nature and degree that, considering the nature and intent of the actor’s conduct and the circumstances known to him, its disregard involves a gross deviation from the standard of conduct that a reasonable person would observe in the actor’s situation.39

Assaults are now a recurring concern for security officers working in domestic and international terrorism. It behooves security policymakers and planners to educate themselves as well as their staff on these criminal acts and corresponding statutes:

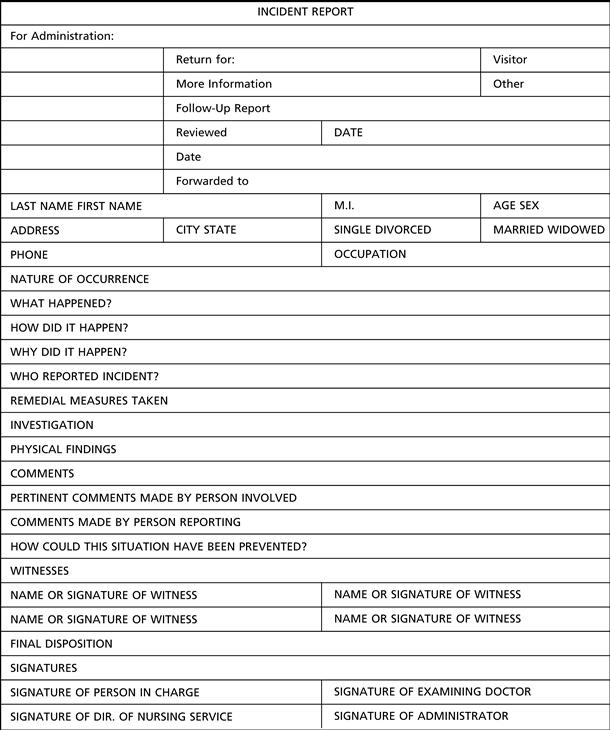

Proof of an assault may or may not require proof of physical injuries. Any injuries alleged can be recorded in the personal injury report shown in Figure 6.2.41

Figure 6.2 Personal Injury Report Form.

Kidnapping and False Imprisonment

Kidnapping and false imprisonment actions are relevant to the security industry because of its heavy involvement in executive protection and counterterrorism. Political figures, military commanders and state guests, as well as traditional celebrities, provide instant targets for our enemies.

Kidnapping consists of the unlawful confinement or restraint of a victim, with an accompanying movement or transportation, for the purpose of ransom, political benefit or other motivation, including the desire to inflict harm. The Model Penal Code sets out the essential elements:

A person is guilty of kidnapping if he unlawfully removes another from his place of residence or business, or a substantial distance from the vicinity where he is found, or if he unlawfully confines another for a substantial period in a place of isolation, with any of the following purposes:

(a) to hold for ransom or reward, or as a shield or hostage; or

(b) to facilitate commission of any felony or flight thereafter; or

(c) to inflict bodily injury on or to terrorize the victim or another; or

(d) to interfere with the performance of any government or political function.42

While most of this codification is clear on its face, legal scholars and advocates frequently contest the transportation or “carrying away” requirement. Modern interpretation, which is generally rather liberal, rejects the view of geographic transfer that is from one locale to another and adopts the “any movement” standard as being sufficient.43

Kidnapping is usually coupled with false imprisonment and rightfully so. Security professionals who detain or restrict the movements of a consumer in retail settings, unprotected by merchants’ privilege or other statutory immunity may be criminally liable for false imprisonment. False imprisonment is both a civil and criminal action. Here is a typical construction:

A person commits a misdemeanor if he knowingly restrains another unlawfully so as to interfere substantially with his liberty.44

Any security-based investigation, whereby a suspect’s freedom to move is abridged, rightly or wrongly, can give rise to the claim of false imprisonment. Kelley V. Rea, a principal in the security firm Legal and Security Services, Ltd., highlights this ongoing risk.

We also continue to read a surprising number of cases, arising out of investigations, with allegations of false imprisonment and infliction of emotional distress. Where a person is held against his or her will or where that person is subjected to “outrageous” conduct, such charges may arise. Conducting an “interview” that lasts more than an hour and giving the person interviewed the impression that he or she is not free to leave may trigger a charge of false imprisonment. Long, tough, threatening questioning, particularly if physical threats are made or physical force used, will often lead to infliction of emotional distress allegations.45

Aside from the physical harm, pain and suffering awards for psychic damages tend to be fairly generous when the confinement and detention is without justification.46 The litigiousness of making an accusation or claim should at least prompt a cautious approach on the security claim operative. In cases of criminal conduct, it may be sound to completely turn over the case to public law enforcement.

For a series of damage awards in civil actions for false imprisonment, see http://www.jvra.com/verdict_trak/professional.aspx?page=2&search=491.

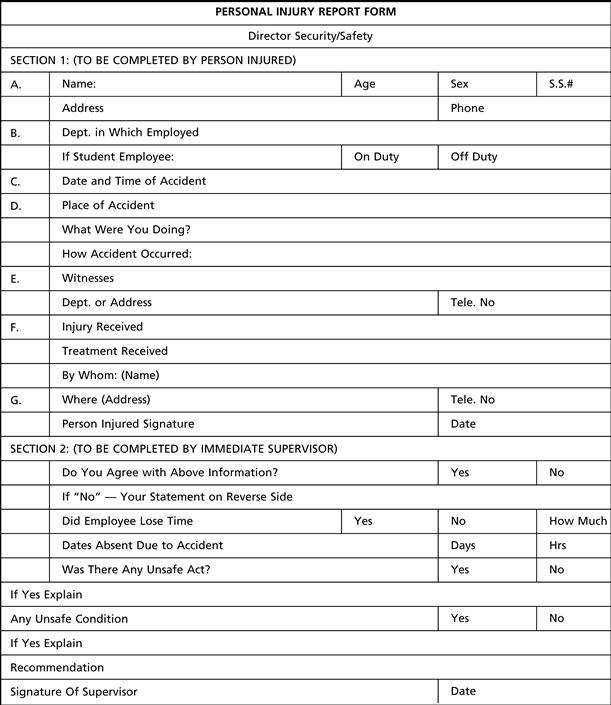

Sexual Offenses

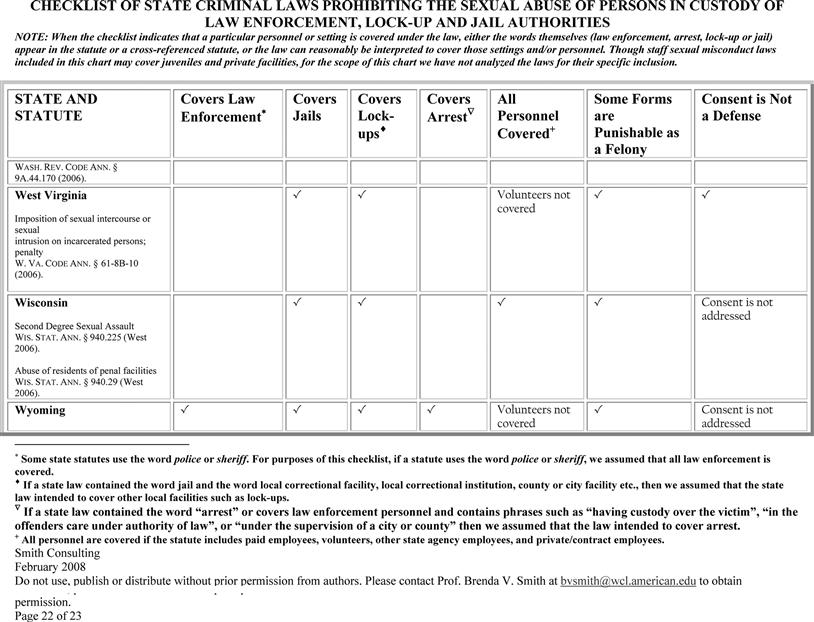

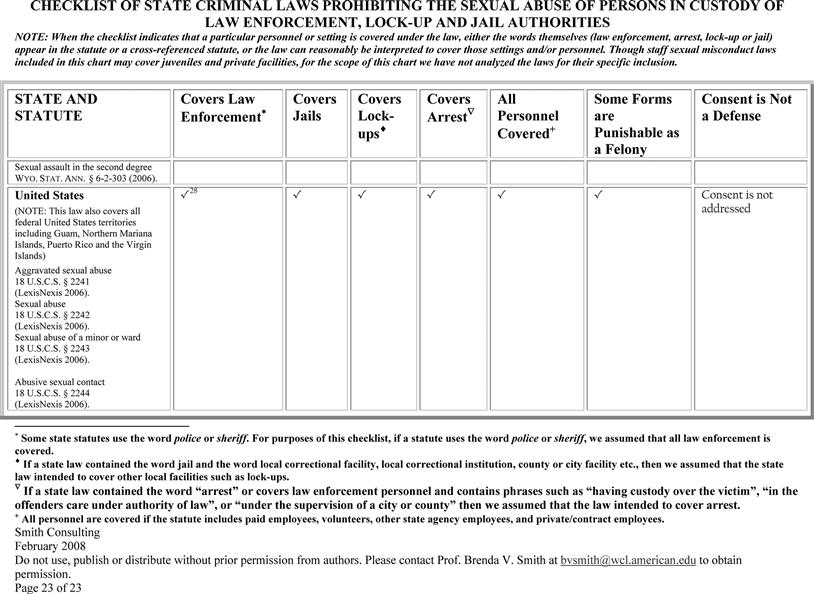

Those entrusted with the task of ensuring safe business and industrial environments now must consider the ramifications of illegal sexual interaction between employers and employees and the increasing sexual victimization of guests, invitees, or licensees on the premises. The investigation and identification of sexual misconduct in the workplace is a major security responsibility. So too in the prison environment, where private prisons operated by private personnel play a central role in providing a safe environment. Most states provide levels of protections and corresponding liability for failure to provide. See Figure 6.3,47 which charts 50 jurisdictions. Negligent hiring and supervision cases are frequently based on the failure of supervision and oversight when hiring or disciplining employees who engage in sexual offenses.48

The American University Law School runs a clearinghouse that announces litigation relating to civil actions and awards in prison settings for sexual abuse. Visit http://www.wcl.american.edu/nic/AnEndtoSilenceYearinNews2008.cfm.

Figure 6.3 Checklist of State Criminal Laws Prohibiting the Sexual Abuse of Persons in Custody.

The tragic violence of rape and aggravated sexual assault will, can, and does occur in any social, commercial, or business setting.49

The Model Penal Code’s sample statute is outlined as follows:

(1) Rape. A male who has sexual intercourse with a female not his wife is guilty of rape if:

While the Model Penal Code lays out the generic elements of sexual offenses, since the 1970s we have witnessed extraordinary efforts to either reform or expand statutory coverage. Proponents of rape law reform have successfully created sexual offense legislation that is gender neutral, that does not require a traditional vaginal and penal contact, and does not weigh the substantiality of victim resistance.51

In business and commercial settings, cases of indecent assault or indecent exposure are not atypical. A representative statute from Pennsylvania covers the standard language:

(3) the complainant suffers from a mental disability which renders the complainant incapable of consent;52

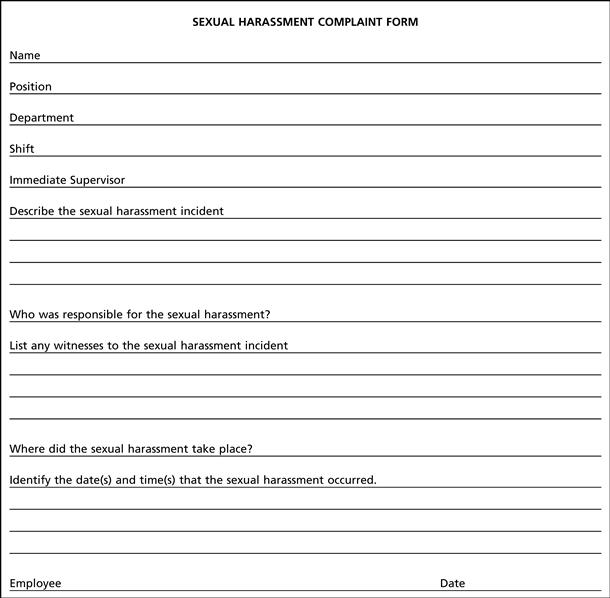

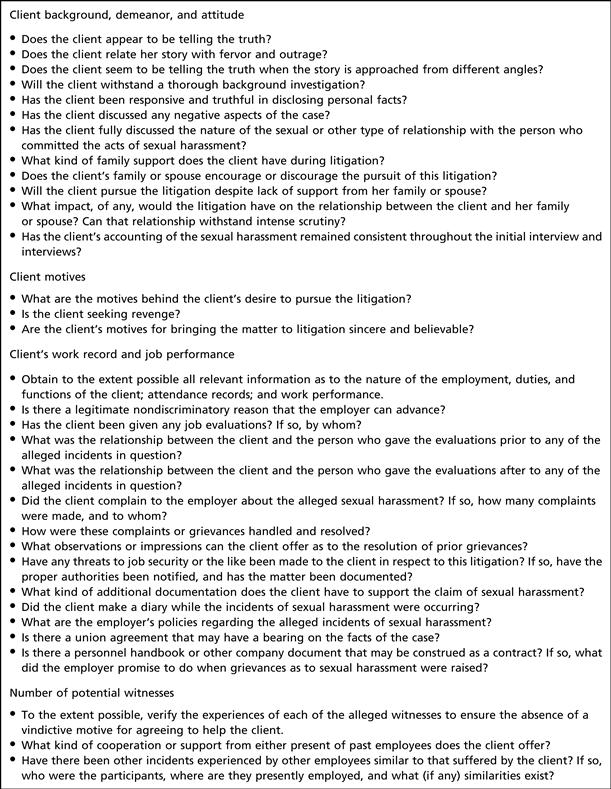

Security companies charged with these types of investigations must memorialize complaints in document form. See Figure 6.4.54 Cases of sexual harassment are unfortunately recurring phenomena for security advisors and consultants. To ferret out the ruses from the legitimate cases of sexual harassment, employ the evaluation checklist shown in Figure 6.5.55

Figure 6.4 Sexual Harassment Complaint Form.

Figure 6.5 Sexual Harassment Evaluation Checklist.

Offenses against the Habitation and Other Buildings

The security industry is entrusted with the protection of homes, business and commercial buildings, and residential settings. Whether by direct patrol or technological surveillance, the industry is increasingly controlling the safety of private residences and business settings.56

Arson

Industrial and business concerns have a grave interest in the protection of their assets and real property from arsonists.57 Around-the-clock security systems, surveillance systems, and electronic technology have done much to aid private enterprise in the protection of its interests.58

Arson, as defined in the Model Penal Code, includes the following provisions:

Judicial interpretation of arson statutes has been primarily concerned with either the definition of a “structure” or in the proof an actual burning or physical fire damage. Structure has been broadly defined as any physical plant, warehouse, or accommodation that permits the carrying on of business or the temporary residents of persons, a domicile, and even ships, trailers, sleeping cars, airplanes, and other movable vehicles or structures.60 Any burning, substantial smoke discoloration and damage, charring, the existence of alligator burn patterns, destruction and damage caused as the results of explosives, detonation devices, and ruination by substantial heat meets the arson criteria. Total destruction or annihilation is not required.61

Most jurisdictions have also adopted related offenses:

• Reckless burning or exploding

• Causing or risking a catastrophe

• Failure to prevent a catastrophe

• Injuring or tampering with fire apparatus, hydrants, etc.

• Unauthorized use or opening of a fire hydrant