THE CONTEMPORARY ROLE AND POWERS OF THE COURTS

11

The contemporary role and powers of the courts

11.1 The role of the courts in the UK constitution

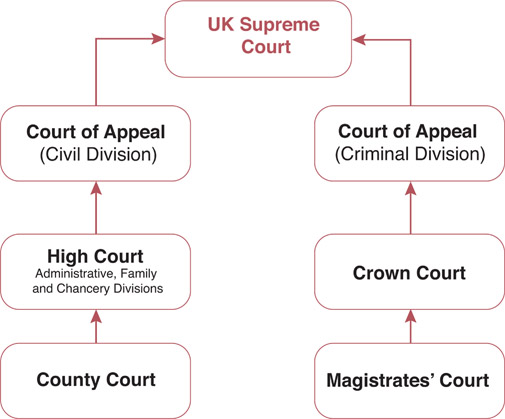

11.1.1 The role of the courts is to offer redress – that is, to be a way for parties to legal disputes to resolve those disputes. The courts are arranged in a structured hierarchy – generally divisible between courts of first instance and appeal courts. The courts are also readily divisible along criminal justice and civil justice lines.

11.1.2 This chapter, however, looks at the less traditional avenues and opportunities for redress: inquiries and ombudsmen, as well as the development of the system of tribunals that more directly support the work of the courts.

11.2 The importance of the separation of powers doctrine in assigning the courts a role in the UK constitution

11.2.1 The separation of powers, as a legal and political doctrine, is the traditional means of explaining the role of the courts in the UK constitution. Under this principle, the courts are not only a place for people to seek legal redress in the event of legal disputes (or for the State to transparently and publicly prosecute and punish criminal offenders).

11.2.2 According to the idea of the separation of powers as outlined in an earlier chapter of this book (Chapter 2), the courts also have a role of checking and balancing the power of the executive (in the United Kingdom, the Government of the day and an array of public bodies – see Chapter 10). Both of these key roles for the courts, and the judiciary in the United Kingdom today, are considered below.

11.2.3 But the courts in the United Kingdom also have a fundamental role in the UK constitution: the creation and maintenance of common law doctrines, or rules – through the steady development of case law, as determined by the senior courts at an appellate level.

11.3 Developing the common law

11.3.1 The judiciary, in determining the outcomes of cases in the courts, both apply the common law, in the form of case law precedent, and also develop that body of case law into the common law itself.

11.3.2 There is no area of the law to which decided cases do not contribute in the form of common law.

11.3.3 The doctrine of precedent ensures that only the most senior judiciary have a role in significantly shaping the common law – since it is the case law produced by the more senior, appellate courts which are the most persuasive or binding precedent.

11.3.4 The Supreme Court, the most senior of the UK courts, determines the direction of the development of the common law on any particular doctrinal issue; that is, on any criminal or civil point of law.

11.4 Engaging in dialogue with Parliament, the Government and European legal structures

11.4.1 The constitutional role of the courts revolves around the work of the judiciary: judges themselves.

11.4.2 More than 21,000 lay magistrates, also known as ‘Justices of the Peace’ or ‘JPs’ sit in panels to try more minor criminal cases in the magistrates’ courts of the United Kingdom, and are assisted by legally qualified professionals in observing court procedure and determining the relevant law. Matters of fact, including the guilt of a defendant ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ – the criminal standard of proof – are determined by the magistrates themselves after hearing evidence from the prosecution and defence.

11.4.3 Juries find defendants guilty ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ in Crown Court trials, overseen by circuit judges. The Judicial Office (as part of the Ministry of Justice) lists more than 600 current circuit judges, who can hear criminal or civil cases, depending on the court in which they sit. Many circuit judges sit in County Courts to try civil cases, without the need for a jury, and where cases are determined on the ‘balance of probability’ – the civil standard of proof.

11.4.4 As noted by the Judicial Office, circuit judges are appointed ‘by the Queen, on the recommendation of the Lord Chancellor, following a fair and open competition administered by the Judicial Appointments Commission’.

11.4.5 The majority of judges working in the County Court are district judges, however. As such, the Judicial Office notes, the ‘work of district judges involves a wide spectrum of civil and family law cases such as claims for damages and injunctions, possession proceedings against mortgage borrowers and property tenants, divorces, child proceedings, domestic violence injunctions and insolvency proceedings’.

11.4.6 High Court judges, as their title implies, sit in the High Court and deal with the most significant cases.

11.4.7 The Judicial Office gives an overview of the structures of the work of the High Court as follows.

The Family Division

‘The Family Division, which deals with family law and probate cases, consists of about 19 judges headed by the President of the Family Division.’

The Chancery Division

‘The Chancery Division deals with company law, partnership claims, conveyancing, land law, probate, patent and taxation cases, and consists of 18 High Court judges, headed by the Chancellor of the High Court. The division includes three specialist courts: the Companies Court, the Patents Court and the Bankruptcy Court. Chancery Division judges normally sit in London, but also hear cases in Cardiff, Bristol, Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds and Newcastle.’

The Queen’s Bench Division

‘The Queen’s Bench Division deals with contract and tort (civil wrongs), judicial reviews and libel, and includes specialist courts: the Commercial Court, the Admiralty Court and the Administration Court. It consists of about 73 judges, headed by the President of the Queen’s Bench Division.’

11.4.8 It is the Administration Court as part of the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court which is the guardian and the forum for applications for judicial review – the core focus of many of the following chapters in this book.

11.4.9 The Lords Justices of Appeal sit in panels to hear cases in the Criminal and Civil Divisions of the Court of Appeal respectively.

11.4.10 The Judicial Office notes that:

‘The Civil Division hears appeals from the High Court, county courts and certain tribunals such as the Employment Appeal Tribunal and the Immigration Appeal Tribunal. Its President is the Master of the Rolls. Cases are generally heard by three judges, consisting of any combination of the Heads of Division and Lords Justices of Appeal.’

‘The Criminal Division hears appeals from the Crown Court. Its President is the Lord Chief Justice. Again, cases are generally heard by three judges, consisting of the Lord Chief Justice or the President of the Queen’s Bench Division or one of the Lords Justices of Appeal, together with two High Court Judges or one High Court Judge and one specially nominated Senior Circuit Judge.’

11.4.11 The 12 Supreme Court Justices decide cases on appeal before the Supreme Court, sitting in panels of five, seven or nine – with a greater number of these most senior of the UK judiciary the more important the matter in the case(s) to be decided.

11.4.13 The next few sections of this chapter, for this reason, look at some basic elements of the relationship between the senior judiciary, in their work in both the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court, and Parliament, the Government, and supranational courts like the Court of Justice of the European Union and the European Court of Human Rights.

11.5 Engaging with Parliament

11.5.1 The relationship between the Supreme Court and Parliament is a necessary and subtle exercise in back-and-forth law-making and decision-making, and involves no small amount of political awareness on the part of the most senior judges in the UK court system.

11.5.2 Paterson has acknowledged different forms of ‘judicial activism’ – the political concept of judges consciously and purposefully developing the law in line with their own political views through making decisions which shape the development of the common law in a particular direction.

11.5.3 R (Yemshaw) v London Borough of Hounslow (2011) is arguably an example of such a case. In Yemshaw, the phrase ‘domestic violence’ in a section of the Housing Act 1996 was construed with a much broader meaning relating to direct and indirect forms of abuse per se. This was a move to open up more support from Government bodies to those who suffered not just physical violence from their partners but also ‘abusive psychological behaviour’.

11.5.4 The Supreme Court regularly decides cases like Yemshaw that have enormous repercussions for many individuals.

11.5.5 As Paterson has noted in his book Final Judgment: ‘When it comes to law-making, Parliament has the authority and the power to act, but sometimes lacks the will. The Supreme Court, on the other hand, cannot decide not to decide.’

11.5.7 What Elliott and other academics have called ‘common law constitutionalism’ as evidenced in cases such as Kennedy and HS2, is a currently highly relevant trend, because particular judges, or groups of judges sitting in an appellate panel, appear to be both intellectually and doctrinally paving the way for potential repeal of the Human Rights Act 1998, for example, under the current Conservative Government.

11.5.8 The stance on the issue of ‘open justice’, as discussed in Kennedy, being driven by the common law as much as by, or independently of, Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, is tantamount to a stance that the removal of the ability to rely on ECHR-based case law might not make such difference. In short, ‘common law constitutionalism’ is the notion that the common law will still be the guardian of fundamental democratic rights, even without the influence of the ECHR directly through the Human Rights Act 1998.

11.5.9 The argument that we should explicitly recognise that the senior judiciary are politically opinionated, and even politically motivated, in their work in determining important cases in the senior courts is known as legal realism. Legal realism is not an idea which sits comfortably with a constitution built around an aspiration to a working separation of powers.

11.5.10 If the senior judiciary recognisably stray beyond the constitutional role assigned to them, that is, the role of applying the (primary and secondary) legislation created by Parliament, and in monitoring and scrutinising the work of the executive in implementing those laws whilst in government; then the political impartiality of the judiciary, an important feature of the rule of law, as well as the concept of natural justice, and the doctrine of due process, all become threatened. See Chapter 12.

11.5.11 Public confidence in the judiciary should not be allowed to become precarious as a result of the judiciary being seen to abandon impartiality, since people should feel that cases are fairly dealt with by the judiciary when they seek redress, in order that redress is sought by recourse to the law and not by recourse to other, more unlawful means.