THE CONTEMPORARY ROLE AND POSSIBLE REFORM OF PARLIAMENT

The contemporary role and possible reform of Parliament

9.1 A bicameral Parliament

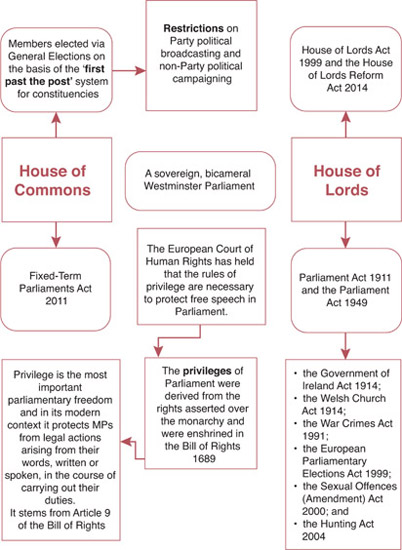

9.1.1 Parliament is the main legislative body in the UK’s constitution. It is a bicameral body, meaning that it is comprised of two chambers, the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

9.1.2 The main functions of Parliament are:

- • to sustain the executive by authorising the raising and spending of funds;

- • to hold the executive to account; and

- • to scrutinise, approve or amend legislation.

9.1.3 Perhaps the most significant of these roles is to secure executive accountability and Parliament attempts to do this using a range of methods.

9.1.4 Parliament’s ability to hold the executive accountable is weakened by the fact that the executive has become dominant. The primary reason for this is the strong Party system that has developed since the early 20th century. The first past the post electoral system supports the creation of a strong, two-Party system and makes it difficult for smaller Parties to win seats.

9.1.5 The ability of Parliament to hold the executive accountable can be impacted on by the Party system in the following ways:

- • the electoral system can result in the Party holding executive power having a large majority;

- • control of parliamentary business and the timetable in the House of Commons rest largely in the hands of the executive; and

- • Parliament exercises its will by voting but each Party has a ‘whip’ system, which is designed to enforce Party discipline and persuade members to vote in a certain way.

9.1.6 The United Kingdom is divided into 659 constituencies, each represented by one Member of Parliament (MP). Each constituency should be approximately the same in terms of voter numbers and distribution and the boundaries should respect local government boundaries. However, in practice there can be considerable differences between constituencies in terms of both geographical size and voting population.

9.1.7 The review of boundaries in a particular part of the United Kingdom is now the responsibility of the relevant Boundary Commissions – for example, the Boundary Commission for England. Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales each have distinct Boundary Commissions.

9.2 The electoral system relevant to the ‘Westminster Parliament’

9.2.1 The principle of universal adult suffrage was not fully realised in the United Kingdom until the 1920s, and is based upon one equal vote per voter. The rules for eligibility of voters are contained in the Representation of the People Act 1983. A voter must be an adult, a citizen of the United Kingdom (or an EU citizen for local elections), and registered on the electoral roll of a local authority.

9.2.2 The following are disqualified from voting:

- • minors;

- • persons subject to a Mental Health Act incapacity;

- • persons serving a prison sentence following conviction (still the case despite the ruling in Hirst v UK (No. 2) (2005));

- • peers of the realm;

- • persons convicted of an electoral offence; and

- • persons who are aliens.

9.2.3 Eligibility for standing as a candidate in a parliamentary General Election is governed by the House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975. The following categories are disqualified:

- • holders of judicial office;

- • civil servants;

- • police officers and members of the armed forces; and

- • Crown appointees.

9.2.4 There are also restrictions upon individual eligibility to stand as a candidate in a General Election:

- • the minimum age is 18;

- • no one may stand who has a mental incapacity;

- • peers may not stand unless they renounce their title;

- • clergymen may not stand while they remain in office;

- • bankrupts may not stand until discharged;

- • persons convicted of treason may not stand until rehabilitated; and

- • persons convicted of electoral offences are banned for a period of five years.

9.2.5 The voting system in the United Kingdom was traditionally a simple majority system known as ‘first past the post’ or ‘plurality’ system. In such a system a winning candidate need achieve only one more vote than the next candidate in a constituency in order to take a seat as a Member of Parliament (MP).

9.2.6 Criticisms of the first past the post system include the fact that it is defective in securing democratic representation since it ignores all votes except for the winning candidate. Hence the smaller political parties and minorities often have little or no representation. For example:

- • in 1951 Labour won more votes than the Conservatives but lost the election;

- • in 1974 the Conservatives won more votes than Labour but lost the election;

- • in 1983 the Liberal Party gained 25% of the votes but won only 3.5% of the seats; and

- • in 2001 Labour won only 40.7% of votes but secured 62.6% of seats in the House of Commons.

9.2.7 In 2005 the General Election results were as follows:

| 2005 General Election (first past the post) | |||

| Party | % votes cast | % of seats | No. of seats |

| Labour | 35.2 | 54.9 | 355 |

| Conservative | 32.4 | 30.7 | 198 |

| Lib Dem | 22.0 | 9.6 | 62 |

| Other | 10.4 | 4.8 | 31 |

In 2010 the General Election results were as follows:

| 2010 General Election (first past the post) | |||

| Party | % votes cast | % of seats | No. of seats |

| Labour | 28.99 | 39.7 | 258 |

| Conservative | 36.48 | 47.2 | 307 |

| Lib Dem | 23.03 | 8.08 | 57 |

| Other | 11.5 | 4.5 | 28 |

| 2015 General Election (first past the post) | |||

| Party | % votes cast | % of seats | No. of seats |

| Conservative | 36.9 | 50.9 | 331 |

| Labour | 30.4 | 35.7 | 232 |

| SNP | 4.7 | 8.6 | 56 |

| Other | 28 | 4.8 | 31 |

9.2.9 It is notable that in ‘Loyal Opposition’ to the Conservative majority Government elected in May 2015, as well as 232 Labour MPs, there sits a group of 56 Scottish Nationalist Party (SNP) MPs, who between them received only 4.7% of the votes cast in the United Kingdom as a whole, but occupy 8.6% of the seats.

9.2.10 Contrast this with the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), whose 12.6% share of the national voting won them a single seat in the Commons.

9.2.11 Outright ‘proportional representation’, with a share of the vote transferred to a straightforward share of 650 seats in the Commons, as opposed to the ‘first past the post’ system currently used, would have secured UKIP more than 50 seats.

At this point we can now address other electoral system formats used in the United Kingdom today.

9.3 Other electoral systems used in the United Kingdom

9.3.1 Recent changes have introduced forms of proportional representation to elect certain representatives and moved the United Kingdom to a position where there is a ‘mixed’ electoral system (see table below). The first past the post system is, however, still currently used to elect Members of Parliament.

| Types of proportional representation system | Used to elect |

| Party List System | Members of the European Parliament (MEP) |

| Additional Member System | Members of the Scottish Parliament (Scotland Act 1998) Members of the Welsh Assembly (Wales Act 1998) Members of the London Assembly (Greater London Authority Act 1999) |

| Single Transferable Vote (Northern Ireland Act 1998) | Members of the Northern Ireland Assembly |

9.3.2 The major political parties considered reform of the electoral system as part of their manifestos for the 2010 General Election with:

- • the Conservative Party advocating continuing with the first past the post system for Westminster;

- • the Labour Party stating that it would hold a referendum by October 2011 on using the Alternative Vote system;

- • the Liberal Democrats stating they would introduce the Single Transferable Vote system and multi-member constituencies and reduce the number of MPs to 500.

9.3.3 The Conservative-Liberal Democrat Coalition Agreement 2010 led to a national referendum in 2011 on the introduction of the Alternative Vote system of electing Members of Parliament to the House of Commons, which was rejected.

9.4 The Electoral Commission and controls on lobbying and campaigning

9.4.1 The Electoral Commission is an independent body that monitors and regulates elections of different kinds, including General Elections, across the United Kingdom.

9.4.2 The Law Commission of England and Wales, the Scottish Law Commission and the Northern Ireland Law Commission jointly consulted over the body of electoral law in the United Kingdom, with a view to possible reforms after the summer of 2015. With this in mind the Law Commission produced an overview of electoral law as part of a consultation paper from late 2014, and which informs this section of this chapter.

9.4.3 The Electoral Commission itself also produces basic guides to electoral processes each time a significant election approaches, and the legal position in this section of this chapter is also based on this material, and is accurate at the time of writing in May 2015. See http://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/ for further details and updates.

9.4.5 The Electoral Commission was established under the PPERA 2000 as a new independent body charged with responsibility for all aspects of elections, local and general or regional, in the United Kingdom. The body as a whole is accountable to Parliament.

9.4.6 The Electoral Commission’s duties include:

- • reporting on the administration of elections;

- • reviewing law and practice;

- • promoting awareness of issues and systems to the public; and

- • compiling an annual report.

9.4.7 The Commission deals with issues relating to the transparency of political campaigns and parties, for example:

- • registrations of donations received;

- • monitoring of bans on foreign donations;

- • control of campaign expenditure;

- • maintenance of various registers; and

- • monitoring of compliance with the PPERA 2000.

9.4.8 One important role is to regulate the funding of political parties. The PPERA 2000 defines permissible and impermissible donors and requires the disclosure and recording by the Commission of donations. Anonymous or unidentifiable donations are impermissible.

9.4.9 An impermissible donation should be returned to the donor; if it is from an unidentifiable source it should be returned to the Commission. The Commission may apply for a court order if an impermissible donation is accepted.

9.4.10 The Political Parties and Elections Act 2009 granted the Commission a variety of additional supervisory and investigatory powers; increased the transparency of donations to political Parties; and proposed a range of new civil sanctions that may be imposed on donees and political Parties.

9.4.11 The Electoral Commission is also responsible for monitoring compliance with the Transparency of Lobbying, Non Party Campaigning and Trade Union Administration Act 2014 (‘the Lobbying Act’), which affected the responsibilities of ‘non-party campaigners’.

- • £319,800 in England;

- • £55,400 in Scotland;

- • £44,000 in Wales; and

- • £30,800 in Northern Ireland.

9.4.13 Perhaps most importantly, non-Party campaigning groups can only spend a maximum of £9,750 per constituency in the build-up to an election – greatly limiting their ability to advocate in favour of a particular candidate in crucial constituencies for a particular political Party.

9.4.14 This new regulation of non-Party campaigning groups was introduced to increase transparency in the way that financial support is indirectly marshalled behind particular political Parties.

9.4.15 The Commission continues to review the future development of electoral systems and regulations and produces consultation documents on new ideas such as the expansion of electronic voting systems. In particular, the impact of the new Lobbying Act will be reviewed by Government in an inquiry led by Lord Hodgson, beginning in 2015. (Critics of the Lobbying Act 2014 have called the legislation the ‘Gagging Act’ because of the way that it limited spending on political awareness-raising by non-Party campaigning organisations, such as trade unions, which naturally support the Labour Party, in the run-up to the General Election 2015.)