SUITS CONCERNING PROPERTY

3

SUITS CONCERNING PROPERTY

CASE VIII: LYSIAS 32 – AGAINST DIOGEITON

The speech against Diogeiton does not survive in its entirety. It owes its preservation not to the medieval manuscript tradition of Lysias but to the fact that it was cited by the critic Dionysios of Halikarnassos, who lived in Rome during the first century BC, as an example of Lysias’ style. Dionysios quoted only part of the speech. It is a suit for impropriety in the conduct of the position of guardian (dike epitropes), and concerns the children of a man named Diodotos. Diodotos had married the daughter of his brother Diogeiton (a common occurrence) before heading off to war, leaving behind a will which made his brother guardian of his young sons and their sister. Diodotos never returned, and it is alleged that over a period of years Diogeiton systematically plundered the estate, while also failing to provide for Diodotos’ widow and daughter (both of whom were subsequently married) the dowries anticipated by Diodotos. Under Athenian law an orphan (by which is meant a fatherless child) could on reaching the age of majority require from his guardian a full financial account for the period of the wardship, and could then sue (by dike epitropes, ‘suit for guardianship’) if he believed that the estate had been managed in a dishonest manner. At least one of the boys is now of age, possibly both. The case for the prosecution however is presented not by the older boy but by the husband of their sister, who is acting as supporting speaker (synegoros), presumably because of the boys’ youth. The date can be fixed fairly closely. Diodotos died on an expedition which can be dated to 410/9. The older boy came of age between seven and eight years later (§9; the Greek, counting inclusively, says ‘in the eighth year’), that is in 403/2 or 402/1. Since Diodotos has been delaying the case, we may plausibly put the hearing in 402/1 or 401/400. There is a commentary on this speech in C. Carey, Lysias: Selected Speeches (Cambridge 1989).

[4] Diodotos and Diogeiton were brothers, judges, by the same father and mother. They divided up their invisible property and held their visible property jointly. When Diodotos had made a substantial profit from trade, he was persuaded by Diogeiton to take the latter’s only daughter in marriage. By her he had two sons and a daughter. [5] Some time later Diodotos was conscripted to serve as a hoplite under Thrasyllos. He called to him his wife, who was also his niece, and her father, who was his father-in-law and his brother, and grandfather and uncle to the children. Thinking that in view of these close bonds no-one had a stronger duty to do right by his children, Diodotos handed a will to him and five silver talents for his safe keeping. [6] He disclosed to him that there were seven talents and 40 mnai lent out on maritime loans (two thousand drachmas loaned out on property), and two thousand owed in the Chersonnesos. And he solemnly bound Diogeiton, in the event of his death, to give his wife in marriage with a dowry of a talent and to make her a gift of the contents of the bedroom, and to give his daughter in marriage with a dowry of a talent. He also left his wife twenty mnai and thirty Kyzikene staters.

[7] Having seen to this he left a copy of the documents in his house and went off to serve with Thrasyllos. After his death at Ephesos, Diogeiton concealed her husband’s death from his daughter for a while, and collected the sealed documents, which Diodotos had left behind, on the pretext that he needed these documents to collect the maritime debt. [8] When he finally revealed the death to them and they had carried out the customary rites, for the first year they lived in Peiraieus, where all the stores had been left. When this supply ran out, he sent the children to the city and gave their mother in marriage with a dowry of five thousand drachmas, one thousand less than her husband had given. [9] Over seven years later, when the older of the lads passed his scrutiny for manhood, Diogeiton called them to him and told them that their father had left them twenty silver mnai and thirty staters. ‘Now, I have spent a good deal of my own money on your keep. While I was able to do so, I did not mind; but now I too am short of money. So as for you, now that you have passed your scrutiny and become a man, you must see to your needs for yourself.’

[10] On hearing this they went to their mother, shocked and weeping, and brought her along with them to my house. They were in a pitiful state, ejected miserably from their home, weeping and urging me not to stand by while they were robbed of their inheritance and reduced to beggary, treated outrageously by those who least should do so, but to help them for their sister’s sake and their own. [11] It would take a long time to describe the extent of the grieving in my house at that point. But finally their mother implored and entreated me to arrange a meeting of her father and their friends. She said that even though she had previously not been in the habit of speaking in the presence of men, the magnitude of their misfortunes would compel her to tell the whole tale of their sufferings to us.

[12] I went and complained to Hegemon, who was now married to Diogeiton’s daughter, I spoke to the rest of our circle of friends, and I demanded that Diogeiton submit to an investigation in the matter of the money. Initially he refused, but finally he was forced into it by his friends. When we met, the woman asked him what state of mind induced him to adopt such an attitude toward the boys, ‘when you are their father’s brother and my father, both their uncle and their grandfather. [13] If you had no respect for any mortal,’ she said, ‘you should have feared the gods. For you certainly received five talents for safekeeping from Diodotos when he was setting sail. On this matter I am ready to stand my children beside me, both these ones and those I bore afterwards, and take an oath by them anywhere my father says. I am not so utterly lost, nor do I value money so much, as to die having perjured myself on the lives of my own children and deprive my father dishonestly of his property.’

[14] Furthermore, she demonstrated that he had taken receipt of seven talents and four thousand drachmas, which had been loaned at maritime rates, and she showed the documents relating to these. She said that during the process of separation, when Diogeiton was moving away from Kollytos into Phaidros’ house, the boys found a discarded book roll and brought it .to her. [15] She demonstrated that he had received one hundred mnai which had been lent out at real estate rates, another two thousand drachmas and valuable furniture; and she said that the family received grain from Chersonnesos every year. ‘And then did you have the nerve,’ she said, ‘when you had so much money, to claim that their father left behind two thousand drachmas and thirty staters, the very sums which were left to me and which I handed to you after his death? [16] And you saw fit to eject these boys, your own grandsons, from their own house dressed only in short cloaks, barefoot, without attendant, without coverlets, without robes, without the furniture their father left them, and without the sums of money he left with you to keep safe for them. [17] And now you are bringing up my stepmother’s children in wealth and luxury (which is fine in itself), while you mistreat my sons; you have driven them without respect from their home and are keen to reduce them from riches to rags. And for acts such as these you show no fear before the gods nor shame before myself, who know the truth, nor loyalty to your brother’s memory; you regard all of us as less important than money.’

[18] At that point judges, having heard the woman’s long and dreadful tale, all of us who were there were so shocked by Diogeiton’s conduct and her speech, as we saw what the boys had suffered, and thought of the dead man and how unworthy was the guardian he left in charge of his estate, and reflected how difficult it is to find someone to trust with one’s property, that none of us present, judges, was able to speak; weeping every bit as bitterly as the victims, we went out in silence.

First of all, will the witnesses to these facts please step up.

Witnesses

[19] I wish you to pay attention to his accounting, judges; then you will pity the young men for the magnitude of their misfortunes and conclude that this man deserves the anger of the whole citizen population. For Diogeiton creates such mutual suspicion in all mankind that in life and in death they have no more confidence in their closest relatives than in their most bitter enemies. [20] This man had the nerve to deny the existence of some of the money and having finally admitted to possessing the rest to declare receipt and expenditure of seven silver talents and four thousand drachmas for the upkeep of two boys and their sister in eight years. Such was his brazenness that, at a loss how to account for the money, he calculated five obols a day for food for two little boys and their sister; for footwear and clothing and the barber’s shop he had not entered a monthly or annual figure but a sum total for the whole period of more than a silver talent. [2l] For their father’s memorial, though he spent less than twenty-five mnai from the declared sum of five thousand drachmas, he puts half of the latter figure down to himself and enters the other half against the boys. Again, he declared the purchase of a lamb for the Dionysia, judges – and I don’t think it unreasonable of me to include this point – at a cost of sixteen drachmas, and put down eight drachmas to the boys. This enraged us as much as anything. As you can see, judges, amid large losses sometimes the small ones cause just as much pain to the victims; they reveal the dishonesty of the wrongdoer all too clearly. [22] For the rest of the festivals and sacrifices he set down to them expenditure of over four thousand drachmas, and a vast number of other payments which were included in the total, as though the sole reason he was appointed guardian to the boys was to present them with sums, not sums of money, and reduce them from riches to absolute rags, and to ensure they would forget any ancestral enemy they might have and wage war on their guardian for defrauding them of their inheritance.

[23] Yet if he had wanted to deal fairly with the boys, it was open to him under the laws relating to orphans, which are applicable to anyone whether able or unable to act as guardian, to lease out the property and be rid of a great deal of trouble, or to purchase property and support the boys from the income. Whichever of these courses he chose, they would have been as rich as anyone in Athens. As it stands, I think it was never his intention to make the extent of their property visible but to keep for himself what belonged to them; he thought his dishonesty should inherit the dead man’s wealth.

[24] The worst thing of all, judges, is that this man, when he was serving as joint-trierarch with Alexis the son of Aristodikos, claimed that he had contributed forty-eight mnai, half of which he has charged to these boys who are orphans; yet the city has not only made orphans exempt when they are children, but has released them from all public services for a year even when they pass their scrutiny for manhood. But this man, their grandfather, illegally exacts half the cost of his own trierarchy from his daughter’s children. [25] And he sent a merchant ship with a cargo worth two talents to the Adriatic. When he was sending it out, he told their mother that it was at the risk of the children, but when it returned safe and doubled the value, he maintained that the enterprise was his. Yet if he is to set down the losses as belonging to the boys but keep the money that comes back as his own, he will have no difficulty in finding sources of expense to enter in his accounts, and will find it easy to become personally rich from the property of others.

[26] To give you a detailed account, judges, would take a great deal of time. However, when after great difficulty they received the written account from him, I asked Aristodikos the brother of Alexis (Alexis himself was by now dead) in front of witnesses if he still had the account for the trierarchy. He said he did, and when we went to his house we found that Diogeiton had contributed twenty-four mnai to the trierarchy. [27] But Diogeiton had declared an expenditure of forty-eight mnai; so he has counted against the boys a sum equal to the whole of his outlay. But what do you imagine he has done on matters where no-one knew the facts and which he handled personally alone, when on business which was done through others, where it was not difficult to discover the facts, he had the nerve to tell lies and extract twenty-four mnai from his own grandsons? Will the witnesses to these facts please step up.

Witnesses

[28] You have heard the witnesses, judges. What I shall do is calculate for him on the basis of the amount which he finally admitted to possessing, seven talents and forty mnai. I shall reckon in no income, but shall spend solely from the capital; and I shall suppose something without precedent in the city, an outlay of a thousand drachmas a year, a little less than three drachmas a day for two boys, their sister, an attendant for the boys and a maidservant. [29] In eight years the total is eight thousand drachmas. This leaves six talents from the seven and twenty mnai (from the forty). He cannot prove that he was robbed of this by pirates or that he lost it in business or that he has repaid debts …

The sums left by Diodotos on his death were (according to the speaker) as follows:

| Left with Diogeiton (§5) | 5 talents | |

| Invested in maritime loans (§6) | 7 talents | 40 mnai |

| Invested in the Chersonnese (§6) | 20 mnai | |

| Invested in real estate loans (§15) | 1 talent | 40 mnai |

| Left to Diogeiton’s wife (§15) | 28 mnai | |

| Unspecified (§15) | 20 mnai | |

| Total | 15 talents | 28 mnai |

The final figure is approximate, since the sum left to the widow (§15) and handed over by her to Diogeiton was partly in the currency of Kyzikos, but the scale of the alleged estate can be gauged from the fact that property of three talents and over rendered a man liable to the liturgy system which served as the Athenian equivalent to wealth tax (see the introduction to Case IV, Antiphon 6 on p. 58). The accuracy of the figure cannot be determined with confidence, however, since for at least one major item (the five talents in cash entrusted to Diogeiton, §5) the only surviving witnesses were Diogeiton and the dead man’s widow, and there is no reason to suppose that the account book supposedly found by the boys (§14) was comprehensive.

But although the scale of the estate is open to question, the fact of fraud seems inescapable. At least one (§27) and possibly more (depending on the nature of the witness testimony in §18) of his alleged frauds is authenticated by witness evidence, and the accounts rendered by Diogeiton (even if we allow for some exaggeration by the speaker) were patently implausible. On the other hand, the speaker ignores the fact that the period of Diogeiton’s administration included the tail-end of the Peloponnesian War (culminating in the siege of Athens by Sparta and her allies) and the aftermath of oligarchy followed by civil war. Not all of the financial damage suffered by the orphans will have been due to Diogeiton’s fraud.

The speech is exceedingly well crafted. A financial suit of this sort is by nature likely either to bore or confuse an audience. Lysias does not attempt to work through the accounts systematically but seizes a few items which exemplify Diogeiton’s dishonesty. Particular attention is paid in the narrative to the characterization of Diogeiton. Lysias presents us with a plausible villain (even where he offers no corroborative evidence) by striving for consistency in the actions narrated. Diogeiton conceals the scale of the estate as he conceals his brother’s death. He cheats on his daughter’s dowry, as he cheats his wards by cunningly transferring to them the whole cost of sacrifice (§21), funeral monument (§2l) or liturgy (§24, §26) disguised as half the cost. And he persistently avoids attempts to resolve the dispute (§2, §12). But perhaps the finest touch in the speech is the use of the widow, Diogeiton’s daughter. As Todd has noted (The Shape of Athenian Law, 203), the quotation of the woman’s speech to her father allows Lysias to circumvent to some degree one of the procedural limitations of the Athenian courts, the fact that women could not appear in any capacity. Yet Diogeiton’s daughter is the only one (beside Diogeiton himself) who has personal knowledge of his depredations. The use of direct speech creates the illusion that we are actually hearing the woman herself. It also allows the speaker to achieve pronounced emotional effects while maintaining for himself the restrained personality appropriate to an individual embroiled in a dispute with kin.

CASE IX: ISAIOS 3 – ON THE ESTATE OF PYRRHOS

[AGAINST NIKODEMOS FOR FALSE TESTIMONY]

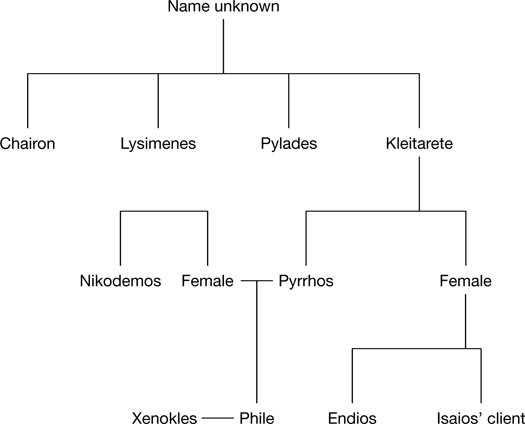

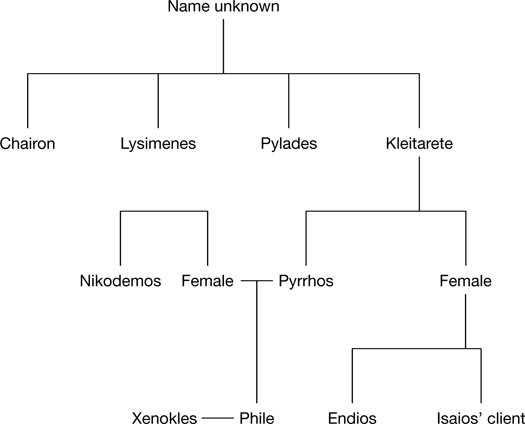

There were in Athens two formal means of checking a legal move by an opponent. The older process, called diamartyria, consisted (as the derivation from martys, ‘witness’, suggests) of a formal affirmation of a fact which made a given action invalid. The affirmation stood, and the action in question was ruled out, unless the opponent brought an action for false testimony against the individual who made the assertion. The diamartyria declined in importance from the end of the fifth century (overtaken by the newer and more flexible paragraphe, for which see the introduction to Dem. 35 on p. 136), and during the fourth century it remained in common use only in inheritance cases, where it was normally used to prevent claims to an estate on the grounds that the dead man had left legitimate issue, to whom the estate would automatically go. The present case arises from a diamartyria lodged by claimants to the estate of Pyrrhos. The diagram makes the relationships clearer.

According to the speaker, his brother Endios had been adopted by their uncle Pyrrhos. Though his claim to the estate was not contested during his life, on his death the estate was claimed by Xenokles on behalf of his wife Phile. Xenokles issued an affirmation (diamartyria), that his wife was the legitimate daughter of Pyrrhos. The way to counter a diamartyria was through a suit for false testimony (dike pseudomartyrion) and Xenokles was successfully prosecuted for false testimony by the speaker of Isai. 3, Endios’ brother, who is claiming the estate on behalf of his mother, Pyrrhos’ sister. At the trial for false testimony Xenokles was supported by Phile’s uncle Nikodemos, who testified that he had given his sister, the mother of Phile, in marriage to Pyrrhos, so that Phile was the legitimate issue of Pyrrhos. Nikodemos too is now being sued for false testimony. The speaker’s aim is probably to preclude further claims on behalf of Phile.

[3] When our mother, who was Pyrrhos’ sister, disputed the claim, the representative of the woman who had claimed the estate had the nerve to enter an affirmation that her brother’s estate was not open to a claim from our mother because of the existence of a legitimate daughter of Pyrrhos, the original owner. We formally opposed the affirmation and brought into court the man who dared to enter it. [4] We proved conclusively that he had made a false deposition and won the case for false testimony in your court, and before the same judges we at once exposed this man Nikodemos as a man quite without shame for this deposition of his; he actually had the nerve to testify that he formally bestowed his sister on my uncle as his legal wife. [5] That his testimony was considered false in the previous suit is shown quite clearly by the conviction of the witness on that occasion. For if it was not believed that Nikodemos gave false evidence, clearly Xenokles would have left the court acquitted in the suit arising from his affirmation, and the woman he averred was the legitimate daughter would have become the heir to my uncle’s property instead of our mother. [6] But since the original witness was convicted and the woman who claimed to be Pyrrhos’ legitimate daughter abandoned her claim to the inheritance, it follows inevitably that Nikodemos’ testimony was condemned at the same time. For it was for entering an affirmation on this very fact that Xenokles was tried for false witness, to establish whether the woman claiming the inheritance was my uncle’s daughter by a wedded wife or a mistress. You too will see this when you hear our sworn declaration and his deposition and the affirmation against which judgment was given. [7] Take these and read them out.

Sworn declaration, deposition, affirmation

It has been shown that Nikodemos was deemed there and then to have given false evidence. But it’s right that his deposition should be refuted before you too, since you are about to reach a verdict on this same issue. [8] But first of all I wish to ask, with reference to this same point, what dowry he claims to have given, this man who has deposed that he gave his sister in marriage to the owner of an estate worth three talents; secondly whether the wedded wife left her husband while he was still alive or left his house after his death, and from whom he recovered his sister’s dowry on the death of the man to whom according to his testimony he gave her. [9] If he could not recover it, is there any action for maintenance or for the actual dowry which he has seen fit to bring during twenty years against the man in possession of the estate? Is there a man alive before whom he ever during all that time made a complaint against the heir about his sister’s dowry? I should like to ask this: why on earth were none of these actions taken when the woman involved was a formally married wife (according to his testimony)?

[10] Furthermore, did anyone else formally marry his sister, either any of the people who associated with her before our uncle knew her or those who had relations with her during his acquaintance with her or later after his death? For clearly her brother has given her on the same terms to everyone who has had relations with her. [11] If one had to list all of them, it would take not a little time. If you order me, I shall mention a few of them. But if some of you find it offensive to listen, as it is for me to speak about these matters, I shall present the depositions, which were given in the previous suit, none of which our opponents saw fit to contest formally. Yet when they themselves have admitted that the woman was available to anyone who wanted her, how could one reasonably believe that the same woman was a formally wedded wife? [12] And in fact since they have not formally contested the depositions relating to this particular fact they have admitted it. When you too have heard the actual depositions, you will recognize that this man has blatantly given false evidence and that the verdict of those who judged the action, that since the woman’s birth was irregular she had no right to the inheritance, was fair and lawful. Read them out; and you, please stop the water.

Depositions

[13] That the woman, whom this man has testified that he formally betrothed to our uncle, was a courtesan available to anyone who wanted her and not his wife has been demonstrated to you by the testimony of the rest of his relatives and his neighbours. They have attested that, whenever the defendant’s sister was at my uncle’s house, she was the subject of many battles and serenades and a great deal of disorderly behaviour. [14] Yet I’m sure that nobody would have the nerve to go serenading married women. Nor do married women attend dinners with their husbands or think it proper to dine with outsiders, especially chance acquaintances. But still our opponents did not see fit to enter a formal protest against the man who attested this. To prove the truth of my statements, read the deposition to them again.

Deposition

[15] Read out also the depositions concerning the men who had relations with her, so the judges will know that she was a courtesan available to anyone who wanted her, and that she certainly bore no child by any other man. Read them out to the judges.

Depositions

[16] You should keep in mind the number of people who have attested to you that the woman whom the defendant has attested that he formally betrothed to our uncle was at the disposal of anyone who wanted her, and that there is no sign that she was formally betrothed to or lived in marriage with anyone else. Let’s review the reasons one might imagine for such a woman being formally betrothed, to see if anything of the sort has occurred in the case of my uncle. [17] On occasion before now young men have conceived a passion for women of this sort, and unable to control themselves were led by their folly to damage themselves like this. What more reliable source of information could one have on this matter than the depositions of those who testified for our opponents in the previous trial and a consideration of the probabilities of the case itself? [18] Observe the sheer nerve of their assertions. The man who was about to betroth his sister (so he maintains) and connect her with an estate worth three talents, despite the importance of the business, alleged that a single witness, Pyretides, was present, and our opponents offered an absentee deposition from him at the previous trial. But Pyretides has not acknowledged this deposition, and denies that he deposed or that he knows whether any of it is true.

[19] Here is a clear indication that the deposition they provided was a blatant fraud. You all know that when we are approaching business which is foreseen, for which witnesses are needed, we usually take along our closest friends, those with whom we are on the most intimate terms, but in the case of unforeseen incidents which take us by surprise we all of us use any chance comers as witnesses. [20] And for the actual depositions we have to use as witnesses the people who were actually present, whoever they are. For obtaining an absentee deposition from people who are ill or are about to leave the country every one of us calls upon the most upright of the citizens and those best known to you, [21] and we all arrange the absentee deposition not in front of one witness or two but as many as we possibly can, to ensure that the individual who made the absentee deposition cannot subsequently deny the testimony, and to secure your trust more effectively by having a large number of decent men offer the same testimony. [22] Now when Xenokles went to our processing plant at the mine workings at Besa, he preferred not to rely on people who chanced to be there as witnesses to the eviction but brought with him from the city Diophantos of Sphettos (who spoke for him in the court hearing), Dorotheos of Eleusis, his brother Philochares and numerous other witnesses; he invited them along though the distance from here to there is nearly three hundred stades. [23] But when the betrothal of the grandmother of his own children was at issue Xenokles arranged an absentee deposition in Athens (so he claims); and it is certain that he invited none of his intimates along, but Dionysios of Erchia and Aristolochos of Aithalidai. Our opponents claim that they took the absentee deposition in the city in front of these two witnesses – a deposition of this sort in front of these individuals, whom nobody else would trust on any subject whatsoever. [24] Perhaps one could argue that the matter on which they claim to have obtained the absentee deposition from Pyretides was irrelevant or trivial, and so it’s not surprising that they took it lightly. But how could this be? The action for false testimony against Xenokles turned on this issue, whether his wife was the daughter of a mistress or a properly wedded wife. Well then, if this deposition was true, would he not have thought it right to invite all his intimates along? [25] Yes indeed, in my opinion at least, if the claim was genuine. But one can see that it was not done like this, and that Xenokles took this absentee deposition in front of two passers-by, while Nikodemos here claims that he invited just one witness to accompany him when he betrothed his sister to the owner of an estate worth three talents. [26] And the defendant alleged that Pyretides alone was there with him, though Pyretides denies it, while Lysimenes and his brothers, Chairon and Pylades, say they were present at the betrothal at the invitation of the man who was about to take in marriage a woman of this sort, though they were the groom’s uncles. [27] It is for you now to determine whether the affair seems credible. In my opinion, considering the probabilities, it is much more likely that Pyrrhos would have wished to escape the attention of all his circle, if he was intending to undertake an agreement or an act unworthy of his family, than that he would have invited his own uncles along to witness a mistake of this magnitude.

[28] Another thing that surprises me is that no agreement was made that the giver or the recipient would hold the woman’s dowry. First, if any dowry was given, one would expect that the people who claim they were there would attest the fact. Second, if our uncle was led to contract the marriage by his passion for a woman of her character, clearly the man who was giving the woman in marriage was far more likely to make an agreement that he would personally hold the money for the woman, to ensure that the groom was not at liberty to get rid of his wife whenever he chose. [29] And it was to be expected that the man who was giving the woman in marriage wouldinvite far more witnesses than the man who was marrying a woman of this character. For none of you are unaware of the fact that few such relationships last. Now the man who claims he gave her away maintains that he betrothed his sister to a man with an estate of three talents with a single witness and without any agreement on a dowry, while the uncles have attested that they were present when their nephew accepted in marriage a woman of this character without a dowry.

[30] These same uncles have attested that they were present on their nephew’s invitation at the tenth-day ceremony for the person represented as his daughter. And what I find quite outrageous is the fact that the husband who laid claim to the paternal estate for his wife entered the wife’s name as Phile, while Pyrrhos’ uncles in claiming that they were present at the tenth-day ceremony attested that her father gave her the name Kleitarete after her paternal grandmother. [31] I’m surprised that a man who had been married for over eight years by now did not know his own wife’s name. Moreover, he could not even discover it in advance from his own witnesses; and during all this time his wife’s mother did not tell him her daughter’s name, nor did the uncle himself, Nikodemos. [32] No, instead of her paternal grandmother’s name, if anyone really knew that her father gave her this name, her husband entered her name as Phile, when he was actually claiming her father’s estate for her. Why was that? Was the husband’s intention to deprive his own wife of her claim to the grandmother’s name bestowed by her father? [33] Isn’t it obvious, gentlemen, that the distant events which these people attest have been fabricated by them long after the claim to the estate was made? Otherwise it would not be the case that the people invited to the tenth-day ceremony (so they claim) for Pyrrhos’ daughter, the defendant’s niece, came to court with an accurate recollection from that day, whenever it was, that her father named her Kleitarete at the ceremony, [34] while the closest relatives of all, her husband, uncle and mother, did not know the name of the woman they say is his daughter. There’s no doubt at all that they would know it, if the claim were true. But there will be time to discuss the uncles again later.

[35] Now as for Nikodemos’ testimony, it is not difficult to determine on the basis of the laws themselves that he is clearly guilty of blatant false witness. If someone gives in a dowry a sum which has no value assigned to it, as far as the law is concerned, if the wife leaves her husband or the husband sends away his wife the donor cannot claim back anything which he did not evaluate as part of the dowry; so surely a man who actually claims that he gave his sister in marriage without making an agreement about the dowry is shown up as a patent liar. [36] What did he stand to gain from the betrothal, if it was open to the groom to send his wife away at will? And assuredly it would have been open to him, gentlemen, if he had not made a formal agreement that he would retain a dowry for her. I ask you, would Nikodemos have betrothed his sister to our uncle on these terms? When he knew that throughout her life she had been childless, and when the agreed dowry would become his under the law if anything were to befall the woman before she had children? [37] Do any of you consider Nikodemos so casual about money as to overlook any detail of this sort? I certainly don’t think so. Again, would our uncle have seen fit to accept in marriage the sister of this man, who was indicted for non-citizenship by a member of the phratry to which he claims to belong and retained his citizenship by four votes? To prove the truth of my statements, read out the deposition.

Deposition

[38] Now this is the man who has testified that he betrothed his sister to our uncle without a dowry! Despite the fact that the dowry would become his if anything befell the woman before she had any children. Take now and read out these laws to them as well.

Laws

[39] Do you think that Nikodemos is so casual about money that, if the incident was real, he would not have paid minute attention to his own interests? Certainly he would, in my opinion, since even people who are bestowing their womenfolk as concubines always reach a prior agreement about the sums to be settled on the concubines. But Nikodemos, when he was about to betroth his own sister (so he claims) carried out only the legal requirements relating to the betrothal. This man, who for the small sum of money he desires to gain by addressing you is so keen to behave dishonestly?

[40] Now Nikodemos’ dishonesty is known to the majority of you even without a word from me. So I have no lack of witnesses to every statement about him. But I wish first of all to make the following points to prove his complete unscrupulousness in the matter of this deposition. Tell me, Nikodemos: if you had given your sister formally in marriage to Pyrrhos, and if you knew that she had a surviving legitimate daughter, [41] how is it that you allowed our brother to claim the estate without also claiming the legitimate daughter, the one you claim our uncle left? Did you not realize that by the act of claiming the estate your own niece was being made a bastard? For anyone who laid claim to the estate was making the daughter of the man who left the estate into a bastard. [42] The same applies to Pyrrhos’ act even earlier in adopting my brother as his son. For it is impossible for a man who dies leaving legitimate daughters to make a will or give any of his property to anyone without also bestowing the daughters. You will appreciate this when you hear the actual laws read out. Read out these laws to them.

Laws

[43] Do you think that the man who has testified to the betrothal would have allowed any such thing to take place? When Endios entered and pursued his claim, would he not have disputed the claim on behalf of his niece and submitted an affirmation that her father’s estate was not open to a claim from Endios? And indeed to show that our brother did lay claim to the estate and that nobody disputed his claim, read out the deposition.

Deposition

[44] When this claim had been made, Nikodemos did not dare to dispute his right to the estate nor to submit an affirmation that his niece was the legitimate surviving daughter of Pyrrhos.

[45] Now on the matter of Endios’ claim one might offer a lying excuse; Nikodemos could pretend that they failed to notice, or he could accuse us of lying. Let’s ignore the latter possibility. But when Endios was betrothing your niece to Xenokles, would you have permitted the daughter of the lawful wife of Pyrrhos to be given in marriage as though she was the daughter of a mistress? [46] Wouldn’t you have brought an impeachment before the Archon alleging the mistreatment of the heiress, when she was being abused in this way by the adopted son and deprived of her father’s estate, especially since these are the only actions which carry no risk for the prosecutor and it is open to any volunteer to protect heiresses? [47] For there is no fine attached to impeachments before the Archon, not even if the prosecutors obtain not a single vote cast, and there are no deposits or court fees required for impeachments. The prosecutors are free to impeach without risk to themselves, anyone who wants, while for anyone convicted on an impeachment the most severe penalties are applied. [48] So then, if his niece was our uncle’s daughter by a formally married wife would Nikodemos have permitted her to be given in marriage like the daughter of a mistress? And when it took place, wouldn’t he have brought an impeachment before the Archon alleging that the heiress was being abused by the individual who gave her in marriage like this? If what you have now had the nerve to depose were true, you would have sought vengeance on the guilty party there and then.

Depositions

Now read out the laws also.

Laws

Now take this man’s deposition too.

Deposition

[54] What clearer proof could one offer when prosecuting for false testimony than a demonstration based on the actions of the opponents themselves and all of your laws?

Deposition

[57] A further fact shows that they deny that Endios’ adoption by Pyrrhos took place. They would not otherwise have ignored the last heir to the property and chosen to claim Pyrrhos’ estate on behalf of the woman. For though Pyrrhos had already been dead for over twenty years, Endios died in Metageitnion last year, and they entered the claim for the estate at once, just two days later. [58] The law orders that claims for the estate be made within five years of the heir’s death. So there were two proper courses open to Xenokles’ wife, either to dispute the father’s estate with Endios during his life, or on the death of the adopted son to lay claim to her brother’s estate, especially if, as they claim, Endios had betrothed her to Xenokles as his legitimate sister. [59] For we are all fully aware that any of us may formally lay claim to the estates of brothers, but where there are offspring of legitimate birth none of them needs to enter a claim to the paternal estate. This is a matter which needs no discussion. For you and all the other citizens possess their own paternal property without having laid claim to it. [60] Now our opponents have become so reckless that they claimed that the adopted son did not need to make formal claim to what had been bequeathed him, while for Phile, who they claim is a legitimate daughter left by Pyrrhos, they saw fit to make a claim for her paternal inheritance. But, as I said before, in all cases where men leave legitimate children of their own, those children need not lay formal claim to the paternal property. On the other hand, in all cases where men adopt by testament, these children must lay formal claim to the property bequeathed. [61] In the case of the former, since they are physical issue, nobody would contest the claim to the father’s property, while in the case of adopted sons all the blood relatives see fit to dispute. So to prevent claims to the estate from any chance comer, and in case people dare to represent the estate as vacant and claim it, all adopted sons submit formal claims. [62] So none of you should think that, if Xenokles had thought his wife was legitimate, he would have put in a claim for her father’s estate on her behalf. No, the legitimate daughter would have gone to her father’s property, and if anyone tried to deprive her or oppose her by force, he would have been ejecting her from her father’s property; and the man who opposed her by force would not only have found himself sued on a private charge but would have been the object of a public impeachment before the Archon and his life and all his property would have been at risk.

[63] But ahead of any intervention by Xenokles, if Pyrrhos’ uncles knew that their nephew had left a legitimate daughter and none of us wanted to marry her, they would not have allowed Xenokles, a man without any connection at all with Pyrrhos, to marry and to keep a wife who belonged to them by virtue of birth. This would be bizarre. [64] Women who are given away by their fathers and live in marriage with their husbands (and who better to decide their fate than the father?), even women married like this, are open to claim by their nearest relatives under the law, if their father dies without leaving legitimate brothers to them; and often before now men in established marriages have been deprived of their wives. [65] Well then. If women given in marriage by their fathers are necessarily open to claim according to the law, would any of Pyrrhos’ uncles, if she was a legitimate daughter left by Pyrrhos, have allowed Xenokles to marry and to keep the wife who belonged to them by virtue of birth, and to make him heir to an estate of this size in their place? [66] You should not imagine so, gentlemen. No mortal man hates his own advantage or thinks more of outsiders than he does of himself. So if they maintain that the woman was not open to claim because of Endios’ adoption, and allege that this was their reason for failing to claim her, first you must ask them if they admit Endios was adopted by Pyrrhos even though they have formally contested the evidence of those who testified to that effect, [67] and secondly why they chose to ignore the last heir to Pyrrhos’ property and make a claim in defiance of the law. You should also ask them this: does any legitimate offspring see fit to enter a formal claim to his own property? These questions should be your response to their audacity.

That the woman was open to claim, if she really was a legitimate daughter of the deceased, one can discover most clearly from the laws. [68] For the law states explicitly that a man may dispose of his own property by will as he chooses, if he does not leave legitimate male children. If he leaves female children, he may dispose of the property along with them. So then, a man may give away and bequeath his property if it is with the daughters; but without including the legitimate daughters a man can neither adopt a son nor give any of his property to anyone. [69] So if Pyrrhos adopted Endios as his son without an arrangement for his legitimate daughter, the adoption would have been invalid under the law. If on the other hand he gave in marriage the daughter he left and this was a condition of the adoption, how could you, Pyrrhos’ uncles, have let Endios claim Pyrrhos’ estate without the legitimate daughter (if Pyrrhos had one), especially since you have testified that your nephew solemnly bound you to take care of this child? [70] I suppose, my good man, you may say that you failed to notice. But when Endios betrothed the woman and gave her in marriage, did you, the uncles, allow your own nephew’s daughter to be betrothed to Xenokles like the daughter of a mistress? Especially when you claim that you were present when your nephew formally agreed to have this woman’s mother as his wife according to the laws, and further that you were present by invitation at the feast on her tenth-day ceremony. [71] On top of this (and this is the monstrous part), though you claim that your nephew solemnly bound you to take care of this child, did you take such good care that you allowed her to be betrothed like the daughter of a mistress, and that despite the fact that she bore the name of your own sister, according to your testimony?

[72] From these arguments, gentlemen, and from the facts themselves, one can easily see how far these people surpass the rest of mankind in impudence. Why, if our uncle left a legitimate daughter, did he adopt my brother and leave him behind as his son? Could it be that he had other kin more closely related than ourselves, and that he adopted my brother as his son through a desire to deprive them of the opportunity to claim his daughter? But, since he had no legitimate issue, there is not and never has been anyone more closely related than us, no-one at all. For he had no brother or brother’s sons, and we were his sister’s sons. [73] Well then, perhaps he might have adopted some other relative and granted him the estate and his daughter. But why should he have incurred the outright hostility of any of his relatives, when it was open to him, if he had really married the sister of Nikodemos, to introduce the female who has been represented as his daughter by her into his phratry as his legitimate daughter, leaving her to be claimed along with the whole estate, and solemnly instruct them to admit as his son one of his daughter’s future children? [74] Obviously he would have known precisely in leaving behind an heiress that two alternatives awaited her: either one of us, his closest relatives, would formally claim the heiress and marry her, or, if none of us wanted her, one of these uncles who are now giving evidence, or, failing that, one of the other relatives would claim her under the laws with the whole property in the same way and have her as his wife. [75] So then, this is what he would have achieved if he had introduced the daughter to his phratry without adopting my brother as his son. But in adopting my brother and refusing to admit her to the phratry, he disinherited the bastard daughter, as he should, and left my brother the heir to his property. [76] And indeed, to prove that our uncle did not celebrate a marriage feast, and that he did not see fit to introduce to his phratry the woman alleged by our opponents to be his legitimate daughter, though this is a rule with the phratry, the clerk will read out the deposition of his fellow phratrymen. Read it out; as for you, please stop the water.

Deposition

Now take the deposition showing that he adopted my brother as his son.

Deposition

[77] Now then, are you to consider Nikodemos’ testimony more reliable than what amounts to depositions in absence from our uncle himself? Will anyone try to persuade you that our uncle had as his formally wedded wife a woman who had been available to anyone who wanted her? But you will not be convinced, so at least I think, unless he demonstrates the following to you, as I said at the beginning of my speech. [78] First, what was the dowry when, as he claims, he betrothed his sister to Pyrrhos? Second, did the formally wedded wife appear before any Archon in order to leave her husband or his house, and from whom did he recover her dowry on the death of the man to whom he claims he betrothed her? Or if he demanded the return of the dowry unsuccessfully for twenty years, did Nikodemos ever bring any action for maintenance or for the actual dowry on behalf of the wedded wife against the individual in possession of Pyrrhos’ estate? [79] In addition, let him also show to whom he formally married his sister either before or after Pyrrhos and whether she has had children by anyone else. Demand answers to these questions from him; and don’t forget about the marriage feast in the phratry. For this is not the least important means of refuting his deposition. For obviously if Pyrrhos had been induced to marry her, he would also have been persuaded to hold a marriage feast for her in his phratry, and to introduce to the phratry the woman represented as his legitimate daughter by her. [80] And in his deme, as a man in possession of a property of three talents, if he was married, he would have had to feast the women at the Thesmophoria on behalf of his formally wedded wife and carry out the other public services in the deme appropriate to a property of this magnitude on his wife’s behalf. You will find that none of these has ever taken place. The members of the phratry have testified for you. Now take also the deposition of his demesmen.