SUBSTANTIVE GROUNDS FOR JUDICIAL REVIEW

14

Substantive grounds for judicial review

14.1 An overview of grounds for judicial review

14.1.1 It is extremely difficult to classify the grounds for judicial review since they are broad and can overlap. This was recognised by the House of Lords in Boddington v British Transport Police (1998).

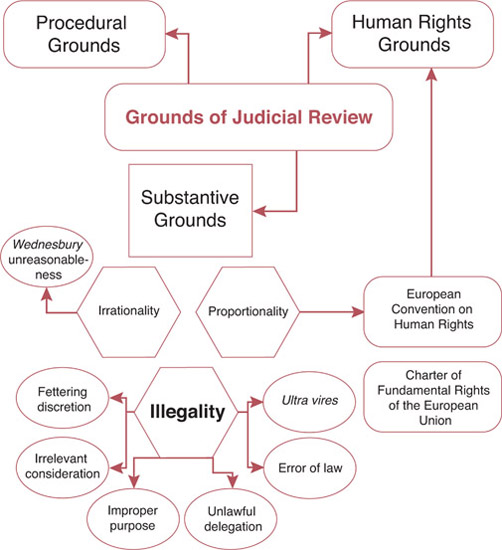

14.1.2 The way this book breaks down grounds of judicial review is to take them in three particular categories:

- • Substantive grounds (dealt with in this chapter);

- • Procedural grounds (dealt with in Chapter 15); and

- • Human rights grounds (dealt with in Chapter 16).

14.1.3 This chapter is mainly concerned with substantive grounds. Substantive grounds are those grounds of judicial review that purport to criticise the overall basis or substance of a decision by a public body – while procedural grounds are concerned with addressing flaws in the manner in which a decision by a public body was actually made.

14.1.4 ‘Human rights grounds’ are what we might call the basis of a claim for an infringement with a human right protected by an Article of the ECHR – in a sense, each protected human right, if breached, can be a distinct human rights-based ground of judicial review in that regard.

14.1.5 A useful starting point (in terms of examining how grounds of judicial review are and have been typically classified) is the classification in Council for Civil Service Unions v Minister for the Civil Service (1985) (the GCHQ Case) where Lord Diplock referred to the following three grounds (however, Lord Diplock recognised that these grounds may overlap and that others may be developed to supplement them):

- • illegality;

- • irrationality; and

- • procedural impropriety.

14.1.6 The first two of these are different groups of substantive grounds, using the classification in this book – and accordingly are dealt with in this chapter. Procedural impropriety makes up the mainstay of the group of procedural grounds – dealt with in Chapter 15.

14.1.7 Grounds that have developed since the decision in the GCHQ Case include:

- • proportionality, particularly since the passing of the Human Rights Act 1998;

- • the particular means of acting unlawfully, on the part of a public body (or ‘hybrid public body’) by contravening section 6 of the Human Rights Act 1998, in breach of an individual’s human rights; and

- • the newer procedural ground of ‘l egitimate expectation’.

14.1.8 Figure 14A at the start of this chapter should therefore be used as a guide in identifying the grounds for judicial review, and is based on the three grounds in the GCHQ Case.

14.2 Types of illegality and the importance of statutory interpretation in deploying arguments about illegality in claiming judicial review

Narrow or simple ultra vires

14.2.1 A body will act in this way when it acts outside of the powers conferred on it: in other words it lacks the necessary jurisdiction.

14.2.2 Lord Diplock in the GCHQ Case defined this as where ‘the decision maker must understand correctly the law that regulates his decision-making power and give effect to it’.

14.2.3 Examples of bodies acting in such a way include:

- • Attorney-General v Fulham Corporation (1921) – in this case statute granted local authorities the power to provide a washhouse for local people. The Corporation interpreted this as granting it the power to provide a laundry service. According to the court this was unlawful because a washhouse was where someone did their own laundry.

- • Bromley London Borough Council v Greater London Council (1983) – the House of Lords held that an obligation on the GLC to provide an ‘efficient and economic’ public transport service did not give the Council the power to subsidise the London Underground for social reasons.

- • R v Lord Chancellor, ex parte Witham (1998) – the Lord Chancellor, under the Supreme Court Act 1981, removed the exemption for payment of court fees for litigants receiving income support. The court found that the Act did not expressly provide for the removal of access to justice and hence the Lord Chancellor had acted ultra vires.

14.2.4 In contrast, in Akumah v Hackney London Borough Council (2005) the House of Lords held that the Council had statutory power to manage, regulate and control ‘dwelling houses’ and this should be interpreted widely to include regulation of car parking. Consequently the Council’s action to clamp cars in a car park attached to a block of flats was held intra vires.

14.2.5 Illegality as a failure to act is where a body has a statutory duty to act and fails to do so. Whether the duty to act is enforceable by the courts will depend on the wording of the statute: if the obligation to act is clear and precise the court will hold it enforceable. Conversely, if the duty is not specific the court will not hold it enforceable. If, under statute, the Secretary of State has default powers to intervene to ensure the duty to act takes place, the courts will generally not intervene: R v Secretary of State for the Environment, ex parte Norwich City Council (1982).

14.3 Illegality as an excess of powers (ultra vires)

14.3.1 The various grounds as types of illegality as considered below are concerned with the way in which bodies exercise their discretion; regardless of how wide a body’s discretion may be, the court can examine whether it has been exercised ultra vires: for example, in relation to an improper purpose: Padfield v Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (1968).

14.4 Illegality as an improper purpose

14.4.1 This is where the body uses its powers to achieve a purpose that it is not empowered to do: see Padfield v Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (1968).

14.4.2 Examples of the application of this ground include:

- • R v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, ex parte World Development Movement (1995) – where the court held that the Minister had acted unlawfully by granting aid to Malaysia because it did not promote development of the country’s economy, as required by statute.

- • Porter v Magill (2002) – the House of Lords ruled that the power of local authorities to sell property to tenants was unlawfully used to secure electoral votes.

14.5 Illegality as an error of law (or an error of fact)

14.5.1 An error of law can take several forms, including incorrect interpretation, whether discretion has been properly exercised and whether irrelevant considerations have been considered or relevant ones ignored.

14.5.2 Generally all errors of law are reviewable: Anisminic Ltd v Foreign Compensation Commission (1969) and R v Lord President of the Privy Council, ex parte Page (1992).

14.5.3 Examples of bodies acting in such a way include:

- • Perilly v Tower Hamlets Borough Council (1973) – the Council had misinterpreted the law so instead of granting stall licences only in order of application, it could grant a licence to the son of a deceased licence holder.

- • R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex parte Venables (1997) – the Home Secretary was held to have misdirected himself as to the law when increasing the tariff for two young murderers on the basis they should be treated as adults.

14.5.4 Errors of fact are not usually reviewable unless they are central to the decision that has been made, for example: if the decision is based on facts for which there is no evidence (Ashbridge Investments v Minister of Housing and Local Government (1965)); and where facts are proved incorrect or have been ignored or misunderstood (R v Criminal Injuries Compensation Board, ex parte A (1992)).

14.5.5 Where the decision involves a person’s individual rights, the courts are more likely to review any error of fact. For example, in R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex parte Khawaja (1984) the court held that whether the applicant was indeed an illegal immigrant had to be determined as fact before the power to detain or expel could be exercised.

14.6 Illegality as a failure to take into account a relevant consideration, or the taking into account of an irrelevant consideration

14.6.1 In exercising its discretion a body must be seen to take into account all relevant considerations and not be swayed in its decision-making by irrelevant ones. It should be noted that this can overlap with the previous ground of improper purpose.

14.6.2 In R v Somerset County Council, ex parte Fewings (1995) three types of consideration were identified:

- • considerations that must be taken into account and which are therefore mandatory;

- • considerations that must not be taken into account and which are therefore prohibited; and

- • discretionary considerations that a decision-maker may have regard to, in which case the court will only intervene if it believes the decision-maker has acted unreasonably.

14.6.3 Examples of the application of this ground include:

- • Wheeler v Leicester City Council (1985) – the decision of a local authority to refuse to permit a local rugby club to use its playing field was found to have been based on the irrelevant consideration that the club had failed to prevent some of its members from touring South Africa during the apartheid regime.

- • R v Talbot Borough Council, ex parte Jones (1988) – the decision to grant priority housing to a divorced councillor was decided on the basis of irrelevant factors, with relevant ones, such as the needs of other applicants on the waiting list, ignored.

- • R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex parte Venables (1997) – the Secretary of State, when reviewing the tariff of child murderers, took into account the irrelevant consideration of public opinion. In R (Bulger) v Secretary of State (2001) it was also concluded that the Home Secretary had failed to take into account the relevant considerations of the progress and development of the children whilst in detention.

- • R v Liverpool Crown Court, ex parte Luxury Leisure (1998) – the court found that the local authority had acted on the basis of relevant considerations when it had considered its knowledge of the area and community when deciding to create a system of permits for amusement arcades.

- • R v Gloucestershire County Council, ex parte Barry (1997) – a local authority, when exercising its statutory obligation to provide care for disabled persons, could take into account its financial resources as a relevant consideration in determining how to meet those needs (see also R v Sefton Metropolitan Borough Council, ex parte Help the Aged (1997)).