STRICT LIABILITY

Strict liability

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Understand the basic concept of strict liability in criminal law

Understand the basic concept of strict liability in criminal law

Understand the tests the courts use to decide whether an offence is one of strict liability

Understand the tests the courts use to decide whether an offence is one of strict liability

Apply the tests to factual situations to determine the existence of strict liability

Apply the tests to factual situations to determine the existence of strict liability

Understand the role of policy in the creation of strict liability offences

Understand the role of policy in the creation of strict liability offences

Analyse critically the concept of strict liability

Analyse critically the concept of strict liability

The previous chapter explained the different types of mens rea. This chapter considers those offences where mens rea is not required in respect of at least one aspect of the actus reus. Such offences are known as strict liability offences. The ‘modern’ type of strict liability offence was first created in the mid-nineteenth century. The first known case on strict liability is thought to be Woodrow (1846) 15 M & W 404. In that case the defendant was convicted of having in his possession adulterated tobacco, even though he did not know that it was adulterated. The judge, Parke B, ruled that he was guilty even if a ‘nice chemical analysis’ was needed to discover that the tobacco was adulterated.

The concept of strict liability appears to contradict the basis of criminal law. Normally criminal law is thought to be based on the culpability of the accused. In strict liability offences there may be no blameworthiness on the part of the defendant. The defendant, as in Woodrow, is guilty simply because he has done a prohibited act.

A more modern example demonstrating this is Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Storkwain Ltd (1986) 2 All ER 635.

CASE EXAMPLE

Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Storkwain Ltd(1986) 2 All ER 635

This case involved s 58(2) of the Medicines Act 1968, which provides that no person shall supply specified medicinal products except in accordance with a prescription given by an appropriate medical practitioner. D had supplied drugs on prescriptions which were later found to be forged. There was no finding that D had acted dishonestly, improperly or even negligently. The forgery was sufficient to deceive the pharmacists. Despite this the House of Lords held that the Divisional Court was right to direct the magistrates to convict D. The pharmacists had supplied the drugs without a genuine prescription, and this was enough to make them guilty of the offence.

For nearly all strict liability offences it must be proved that the defendant did the relevant actus reus. In Woodrow this meant proving that he was in possession of the adulterated tobacco. For Storkwain this meant proving that they had supplied specified medicinal products not in accordance with a prescription given by an appropriate medical practitioner. In these cases it also had to be proved that the doing of the actus reus was voluntary. However, there are a few rare cases where the defendant has been found guilty even though they did not do the actus reus voluntarily. These are known as crimes of absolute liability.

4.1 Absolute liability

Absolute liability means that no mens rea at all is required for the offence. It involves status offences; that is, offences where the actus reus is a state of affairs. The defendant is liable because they have ‘been found’ in a certain situation. Such offences are very rare. To be an absolute liability offence, the following conditions must apply:

The offence does not require any mens rea.

The offence does not require any mens rea.

There is no need to prove that the defendant’s actus reus was voluntary.

There is no need to prove that the defendant’s actus reus was voluntary.

The following two cases demonstrate this. The first is Larsonneur (1933) 24 Cr App R 74.

CASE EXAMPLE

Larsonneur (1933) 24 Cr App R 74

The defendant, who was an alien, had been ordered to leave the United Kingdom. She decided to go to Eire, but the Irish police deported her and took her in police custody back to the United Kingdom, where she was put in a cell in Holyhead police station. She did not want to return to the United Kingdom. She had no mens rea; her act in returning was not voluntary. Despite this she was found guilty under the Aliens Order 1920 of ‘being an alien to whom leave to land in the United Kingdom has been refused’ who was ‘found in the United Kingdom’.

The other case is Winzar v Chief Constable of Kent, The Times, 28 March 1983; Co/1111/82 (Lexis), QBD.

CASE EXAMPLE

Winzar v Chief Constable of Kent, The Times, 28 March 1983

D was taken to hospital on a stretcher, but when doctors examined him they found that he was not ill but was drunk. D was told to leave the hospital but was later found slumped on a seat in a corridor. The police were called and they took D to the roadway outside the hospital. They formed the opinion he was drunk so they put him in the police car, drove him to the police station and charged him with being found drunk in a highway contrary to s 12 of the Licensing Act 1872. The Divisional Court upheld his conviction.

As in Larsonneur, the defendant had not acted voluntarily. The police had taken him to the highway. In the Divisional Court Goff LJ justified the conviction:

JUDGMENT

‘[L]ooking at the purpose of this particular offence, it is designed … to deal with the nuisance which can be caused by persons who are drunk in a public place. This kind of offence is caused quite simply when a person is found drunk in a public place or highway… [A]n example … illustrates how sensible that conclusion is. Suppose a person was found drunk in a restaurant and was asked to leave. If he was asked to leave, he would walk out of the door of the restaurant and would be in a public place or in a highway of his own volition. He would be there of his own volition because he had responded to a request. However, if a man in a restaurant made a thorough nuisance of himself, was asked to leave, objected and was ejected, in those circumstances he would not be in a public place of his own volition because he would have been put there… It would be nonsense if one were to say that the man who responded to the plea to leave could be said to be found drunk in a public place or in a highway, whereas the man who had been compelled to leave could not.

This leads me to the conclusion that a person is “found to be drunk or in a public place or in a highway”, within the meaning of those words as used in the section, when he is perceived to be drunk in a public place. It is enough for the commission of the offence if (1) a person is in a public place or a highway, (2) he is drunk, and (3) in those circumstances he is perceived to be there and to be drunk.’

It is not known how Winzar came to be taken to the hospital on a stretcher, but commentators on this case point out that there may be an element of fault in Winzar’s conduct. He had become drunk, and in order to have been taken to hospital must have either been in a public place when the ambulance collected him and took him to hospital, or he must have summoned medical assistance when he was not ill but only drunk.

4.2 Strict liability

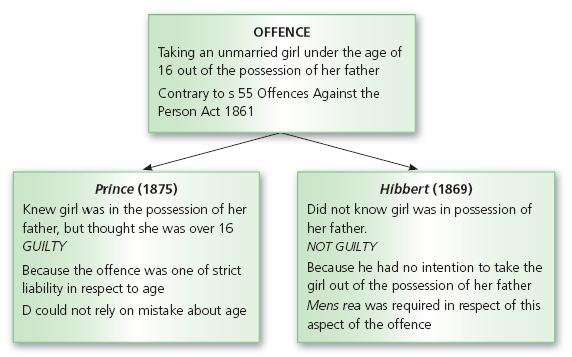

For all offences, there is a presumption that mens rea is required. The courts will always start with this presumption, but if they decide that the offence does not require mens rea for at least part of the actus reus, then the offence is one of strict liability. This idea of not requiring mens rea for part of the offence is illustrated by two cases, Prince (1875) LR 2 CCR 154 and Hibbert (1869) LR 1 CCR 184. In both these cases the charge against the defendant was that he had taken an unmarried girl under the age of 16 out of the possession of her father against his will, contrary to s 55 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861.

Prince knew that the girl he took was in the possession of her father but believed, on reasonable grounds, that she was aged 18. He was convicted, as he had the intention to remove the girl from the possession of her father. Mens rea was required for this part of the actus reus, and he had the necessary intention. However, the court held that knowledge of her age was not required. On this aspect of the offence there was strict liability. In Hibbert the defendant met a girl aged 14 on the street. He took her to another place where they had sexual intercourse. He was acquitted of the offence as it was not proved that he knew the girl was in the custody of her father. Even though the age aspect of the offence was one of strict liability, mens rea was required for the removal aspect, and in this case, the necessary intention was not proved.

As already stated, the actus reus must be proved and the defendant’s conduct in doing the actus reus must be voluntary. However, a defendant can be convicted if his voluntary act inadvertently caused a prohibited consequence. This is so even though the defendant was totally blameless in respect of the consequence, as was seen in Callow v Tillstone (1900) 83 LT 411.

CASE EXAMPLE

Callow v Tillstone (1900) 83 LT 411

A butcher asked a vet to examine a carcass to see if it was fit for human consumption. The vet assured him that it was all right to eat, and so the butcher offered it for sale. In fact it was unfit and the butcher was convicted of the offence of exposing unsound meat for sale. It was a strict liability offence, and even though the butcher had taken reasonable care not to commit the offence, he was still guilty.

4.2.1 No due diligence defence

For some offences, the statute creating the offence provides a defence of due diligence. This means that the defendant will not be liable if he can adduce evidence that he did all that was within his power not to commit the offence. There does not seem, however, to be any sensible pattern for when Parliament decides to include a due diligence defence and when it does not. It can be argued that such a defence should always be available for strict liability offences. If it was, then the butcher in Callow v Tillstone above would not have been guilty. By asking a vet to check the meat he had clearly done all that he could not to commit the offence.

Another example where the defendants took all reasonable steps to prevent the offence but were still guilty, as there was no due diligence defence available, is Harrow LBC v Shah and Shah (1999) 3 All ER 302.

CASE EXAMPLE

Harrow LBC v Shah and Shah (1999) 3 All ER 302

The defendants owned a newsagent’s business where lottery tickets were sold. They had told their staff not to sell tickets to anyone under 16 years. They also told their staff that if there was any doubt about a customer’s age, the staff should ask for proof of age, and if still in doubt should refer the matter to the defendants. In addition there were clear notices up in the shop about the rules, and staff were frequently reminded that they must not sell lottery tickets to underage customers. One of their staff sold a lottery ticket to a 13-year-old boy without asking for proof of age. The salesman mistakenly believed the boy was over 16 years. D1 was in a back room of the premises at the time; D2 was not on the premises.

D1 and D2 were charged with selling a lottery ticket to a person under 16, contrary to s 13(1)(c) of the National Lottery etc. Act 1993 and the relevant Regulations. Section 13(1) (c) provides that ‘Any other person who was a party to the contravention shall be guilty of an offence’. This subsection does not have any provision for a due diligence defence, although s 13(1)(a), which makes the promoter of the lottery guilty, does contain a due diligence defence. Both these offences carry the same maximum sentence (two years’ imprisonment, a fine or both) for conviction after trial on indictment. The magistrates dismissed the charges. The prosecution appealed by way of case stated to the Queen’s Bench Divisional Court.

The Divisional Court held the offence to be one of strict liability. They allowed the appeal and remitted the case to the magistrates to continue the hearing. The Divisional Court held that the offence did not require any mens rea. The act of selling the ticket to someone who was actually under 16 was enough to make the defendants guilty, even though they had done their best to prevent this happening in their shop.

Mens rea

For new statutory offences, a ‘due diligence’ defence is more often provided. However, it is argued that due diligence should be a general defence, as it is in Australia and Canada. The draft Criminal Code of 1989 included provision for a general defence of due diligence, but the Code has never been enacted. (See section 1.2.3.)

4.2.2 No defence of mistake

Another feature of strict liability offences is that the defence of mistake is not available. This is important as, if the defence of mistake is available, the defendant will be acquitted when he made an honest mistake. Two cases which illustrate the difference in liability are Cundy v Le Cocq (1884) 13 QBD 207 and Sherras v De Rutzen (1895) 1 QB 918. Both of these involve contraventions of the Licensing Act 1872.

SECTION

‘13 If any licensed person permits drunkenness or any violent quarrelsome or riotous conduct to take place on his premises, or sells any intoxicating liquor to any drunken person, i he shall be liable to a penalty…’

The magistrate trying the case found as a fact that the defendant and his employees had not noticed that the person was drunk. The magistrate also found that while the person was on the licensed premises he had been ‘quiet in his demeanour and had done nothing to indicate insobriety; and that there were no apparent indications of intoxication’. However, the magistrate held that the offence was complete on proof that a sale had taken place and that the person served was drunk and convicted the defendant. The defendant appealed against this, but the Divisional Court upheld the conviction. Stephen J said:

JUDGMENT

‘I am of the opinion that the words of the section amount to an absolute prohibition of the sale of liquor to a drunken person, and that the existence of a bona fide mistake as to the condition of the person served is not an answer to the charge, but is a matter only for mitigation of the penalties that may be imposed.’

So s 13 of the Licensing Act 1872 was held to be a strict liability offence as the defendant could not rely on the defence of mistake. In contrast it was held in Sherras v De Rutzen that s 16 of the Licensing Act 1872 did not impose strict liability. In that case the defendant was able to rely on the defence of mistake.

CASE EXAMPLE

Sherras v De Rutzen (1895) 1 QB 918

In Sherras the defendant was convicted by a magistrate of an offence under s 16(2) of the Licensing Act 1872. This section makes it an offence for a licensed person to ‘supply any liquor or refreshment’ to any constable on duty. There were no words in the section requiring the defendant to have knowledge that a constable was off duty. The facts were that local police when on duty wore an armband on their uniform. An on-duty police officer removed his armband before entering the defendant’s public house. He was served by the defendant’s daughter in the presence of the defendant. Neither the defendant or his daughter made any enquiry as to whether the policeman was on duty. The defendant thought that the constable was off duty because he was not wearing his armband. The Divisional Court quashed the conviction. They held that the offence was not one of strict liability, and accordingly a genuine mistake provided the defendant with a defence.

When giving judgment in the case Day J stated:

JUDGMENT

‘This police constable comes into the appellant’s house without his armlet, and with every appearance of being off duty. The house was in the immediate neighbourhood of the police station, and the appellant believed, and had very natural grounds for believing, that the constable was off duty. In that belief he accordingly served him with liquor. As a matter of fact, the constable was on duty; but does that fact make the innocent act of the appellant an offence? I do not think it does. He had no intention to do a wrongful act; he acted in the bona fide belief that the constable was off duty. It seems to me that the contention that he committed an offence is utterly erroneous.’

It is difficult to reconcile this decision with the decision in Cundy. In both cases the sections in the Licensing Act 1872 were expressed in similar words. In Cundy the offence was ‘sells any intoxicating liquor to any drunken person’, while in Sherras the offence was ‘supplies any liquor … to any constable on duty’. In each case the publican made a genuine mistake. Day J justified his decision in Sherras by pointing to the fact that although s 16(2) did not include the word ‘knowingly’, s 16(1) did, for the offence of ‘knowingly harbours or knowingly suffers to remain on his premises any constable during any part of the time appointed for such constable being on duty’. Day J held this only had the effect of shifting the burden of proof. For s 16(1) the prosecution had to prove that the defendant knew the constable was on duty, while for s 16(2) the prosecution did not have to prove knowledge, but it was open to the defendant to prove that he did not know.

The other judge in the case of Sherras, Wright J, pointed out that if the offence was to be made one of strict liability, then there was nothing the publican could do to prevent the commission of the crime. No care on the part of the publican could save him from a conviction under s 16(2), since it would be as easy for the constable to deny that he was on duty when asked as to remove his armlet before entering the public house. It is more possible to reconcile the two cases on this basis as in most cases the fact of a person being drunk would be an observable fact, so the publican should be put on alert and could avoid committing the offence.

4.2.3 Summary of strict liability

So where an offence is held to be one of strict liability, the following points apply:

The defendant must be proved to have done the actus reus.

The defendant must be proved to have done the actus reus.

This must be a voluntary act on his part.

This must be a voluntary act on his part.

There is no need to prove mens rea for at least part of the actus reus.

There is no need to prove mens rea for at least part of the actus reus.

No due diligence defence will be available.

No due diligence defence will be available.

The defence of mistake is not available.

The defence of mistake is not available.

These factors are well established. The problem lies in deciding which offences are ones of strict liability. For this the courts will start with presuming that mens rea should apply. This is so for both common law and statutory offences.

4.3 Common law strict liability offences

Nearly all strict liability offences have been created by statute. Strict liability is very rare in common law offences. Only three common law offences have been held to be ones of strict liability. These are

public nuisance

public nuisance

some forms of criminal libel

some forms of criminal libel

outraging public decency

outraging public decency

JUDGMENT

‘Why then should the House, faced with a deliberate publication of that which a jury with every justification has held to be a blasphemous libel, consider that it should be for the prosecution to prove, presumably beyond reasonable doubt, that the accused recognised and intended it to be such… The reason why the law considers that the publication of a blasphemous libel is an offence is that the law considers that such publications should not take place. And if it takes place, and the publication is deliberate, I see no justification for holding that there is no offence when the publisher is incapable, for some reason particular to himself, of agreeing with a jury on the true nature of the publication.’

Note that blasphemous libel has now been abolished by the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008.

Outraging public decency was held to be an offence of strict liability in Gibson and Sylveire (1991) 1 All ER 439 since it does not have to be proved that the defendant intended to or was reckless that his conduct would have the effect of outraging public decency.

Criminal contempt of court used to be a strict liability offence at common law. It is now a statutory offence, and Parliament has continued it as a strict liability offence.

Note that the Law Commission consulted in 2010 on possible reform of the offences of public nuisance and outraging public decency. A report is due out but had not been published at the time of writing the text.

4.4 Statutory strict liability offences

The surprising fact is that about half of all statutory offences are strict liability. This amounts to over 5, 000 offences. Most strict liability offences are regulatory in nature. This may involve such matters as regulating the sale of food and alcohol and gaming tickets, the prevention of pollution and the safe use of vehicles.

In order to decide whether an offence is one of strict liability, the courts start by assuming that mens rea is required, but they are prepared to interpret the offence as one of strict liability if Parliament has expressly or by implication indicated this in the relevant statute. The judges often have difficulty in deciding whether an offence is one of strict liability. The first rule is that where an Act of Parliament includes words indicating mens rea (eg ‘knowingly’, ‘intentionally’, ‘maliciously’ or ‘permitting’), the offence requires mens rea and is not one of strict liability. However, if an Act of Parliament makes it clear that mens rea is not required, the offence will be one of strict liability. An example of this is the Contempt of Court Act 1981 where s 1 sets out the ‘strict liability rule’. It states:

SECTION

‘In this Act “the strict liability rule” means the rule of law whereby conduct may be treated as a contempt of court as tending to interfere with the course of justice in particular legal proceedings regardless of intent to do so.’

Throughout the Act it then states whether the ‘the strict liability rule’ applies to the various offences of contempt of court.

However, in many instances a section in an Act of Parliament is silent about the need for mens rea. Parliament is criticised for this. If they made clear in all sections which create a criminal offence whether mens rea was required, then there would be no problem. As it is, where there are no express words indicating mens rea or strict liability, the courts have to decide which offences are ones of strict liability.

4.4.1 The presumption of mens rea

Where an Act of Parliament does not include any words indicating mens rea, the judges will start by presuming that all criminal offences require mens rea. This was made clear in the case of Sweet v Parsley (1969) 1 All ER 347.

CASE EXAMPLE

Sweet v Parsley (1969) 1 All ER 347

D rented a farmhouse and let it out to students. The police found cannabis at the farmhouse, and the defendant was charged with ‘being concerned in the management of premises used for the purpose of smoking cannabis resin’. The defendant did not know that cannabis was being smoked there. It was decided that she was not guilty as the court presumed that the offence required mens rea.

The key part of the judgment was when Lord Reid said:

JUDGMENT

‘… there has for centuries been a presumption that Parliament did not intend to make criminals of persons who were in no way blameworthy in what they did. That means that, whenever a section is silent as to mens rea, there is a presumption that, in order to give effect to the will of Parliament, we must read in words appropriate to require mens rea … it is firmly established by a host of authorities that mens rea is an ingredient of every offence unless some reason can be found for holding that it is not necessary.’

This principle has been affirmed by the House of Lords in B (a minor) v DPP (2000) 1 All ER 833 where the House of Lords reviewed the law on strict liability. The Law Lords quoted with approval what Lord Reid had said in Sweet v Parsley (see section 4.4.8 for full details of B v DPP).

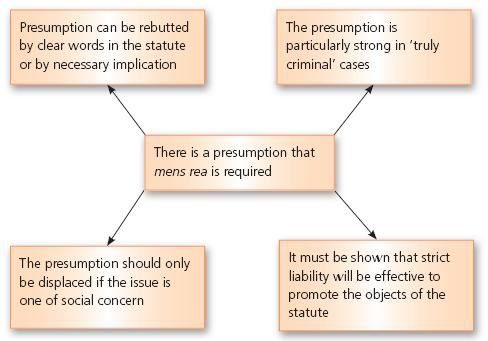

Although the courts start with the presumption that mens rea is required, they look at a variety of points to decide whether the presumption should stand or if it can be displaced and the offence made one of strict liability.

4.4.2 The Gammon criteria

In Gammon (Hong Kong) Ltd v Attorney-General ofHong Kong (1984) 2 All ER 503, the appellants had been charged with deviating from building work in a material way from the approved plan, contrary to the Hong Kong Building Ordinances. It was necessary to decide if it had to be proved that they knew that their deviation was material or whether the offence was one of strict liability on this point. The Privy Council started with the presumption that mens rea is required before a person can be held guilty of a criminal offence but went on to give four other factors to be considered. These were stated by Lord Scarman to be that

The presumption in favour of mens rea being required before D can be convicted applies to statutory offences and can be displaced only if this is clearly or by necessary implication the effect of the statute.

The presumption in favour of mens rea being required before D can be convicted applies to statutory offences and can be displaced only if this is clearly or by necessary implication the effect of the statute.

The presumption is particularly strong where the offence is ‘truly criminal’ in character.

The presumption is particularly strong where the offence is ‘truly criminal’ in character.

The only situation in which the presumption can be displaced is where the statute is concerned with an issue of social concern; public safety is such an issue.

The only situation in which the presumption can be displaced is where the statute is concerned with an issue of social concern; public safety is such an issue.

Even where the statute is concerned with such an issue, the presumption of mens rea stands unless it can be shown that the creation of strict liability will be effective to promote the objects of the statute by encouraging greater vigilance to prevent the commission of the prohibited act.

Even where the statute is concerned with such an issue, the presumption of mens rea stands unless it can be shown that the creation of strict liability will be effective to promote the objects of the statute by encouraging greater vigilance to prevent the commission of the prohibited act.

Figure 4.2 The Gammon criteria

4.4.3 Looking at the wording of an act

As already stated, where words indicating mens rea are used, the offence is not one of strict liability. If the particular section is silent on the point, then the courts will look at other sections in the Act. Where the particular offence has no words of intention, but other sections in the Act do, then it is likely that this offence is a strict liability offence. In Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Storkwain the relevant section, s 58(2) of the Medicines Act 1968, was silent on mens rea. The court looked at other sections in the Act and decided that, as there were express provisions for mens rea in other sections, Parliament had intended s 58(2) to be one of strict liability.

However, the fact that other sections specifically require mens rea does not mean that the courts will automatically make the offence without express words of mens rea one of strict liability. In Sherras, even though s 16(1) of the Licensing Act 1872 had express words requiring knowledge, it was held that mens rea was still required for s 16(2), which did not include the word ‘knowingly’. This point was reinforced in Sweet, when Lord Reid stated:

JUDGMENT

‘It is also firmly established that the fact that other sections of the Act expressly require mens rea, for example because they contain the word “knowingly”, is not of itself sufficient to justify a decision that a section which is silent as to mens rea creates an absolute offence. In the absence of a clear intention in the Act that an offence is intended to be an absolute offence, it is necessary to go outside the Act and examine all relevant circumstances in order to establish that this must have been the intention of Parliament.’

Where other sections allow for a defence of no negligence but another section does not, then this is another possible indicator from within the statute that the offence is meant to be one of strict liability. In Harrow LBC v Shah and Shah the defendants were charged under s 13(1)(c) of the National Lottery etc. Act 1993. The whole of s 13 reads:

SECTION

13(1) If any requirement or restriction imposed by regulations made under section 12 is contravened in relation to the promotion of a lottery that forms part of the National Lottery,

(a) the promoter of the lottery shall be guilty of an offence, except if the contravention occurred without the consent or connivance of the promoter and the promoter exercised all due diligence to prevent such a contravention,

(b) any director, manager, secretary or other similar officer of the promoter, or any person purporting to act in such a capacity, shall be guilty of an offence if he consented to or connived at the contravention or if the contravention was attributable to any neglect on his part, and

(c)