Social control

6

While the topics of dispute resolution and social control are divided into separate chapters, increasingly mechanisms of dispute resolution and social control converge. Several authors point to qualitative differences in concerns about social control and crime from the late twentieth century, including a focus on crime prevention, partnerships between individuals, neighbourhoods, communities and the state, and the control and management of crime being nested in public housing, education, welfare, and transport sectors, not just the criminal justice system.

Contemporary crime control policies often emphasize risk, security and individual responsibility for both the choice to engage in criminal offending and the choice to minimize risk (Garland, 2001). ‘In criminal justice, this has meant less focus on the identification, prosecution and rehabilitation of guilty individuals, and more on identifying, preventing or reducing potential crime risks’ (Mazerolle and Ransley, 2005: 65). Security and harm minimization are not only the concern of the conventional criminal justice agencies.

Policing and surveillance have been uncoupled from the police, governance uncoupled from the government, and crime control uncoupled from the criminal justice system (Roach Anleu, 2006: Chapter 3). There are new participants in the social control edifice – police partnerships and networks among businesses community organizations extend the networks charged with crime prevention and blur civil and criminal categories and methods (Mazerolle and Ransley, 2005: 71). New techniques of social control have become embedded in everyday life, for example Closed Circuit Television (CCTV), speed cameras, bar codes, pin numbers, and so on (Lianos and Douglas, 2000).

This chapter examines the relationship between legal and nonlegal social control and focuses primarily on the criminal justice system in contemporary societies. The criminal justice system is often a site of social engineering and attempts to effect social change by altering the behaviour and opportunities of law breakers and by redefining criminal laws in order to prohibit certain activities and encourage, or at least allow, others. The kinds of criminal laws that exist in a society, the range and types of punishment that are prevalent and the organization and ideology of the criminal justice system can be barometers of wider social trends. For sociologists in the functionalist tradition, social control, of which one type is law, is intimately linked with social integration and the maintenance of social life.

Formal sanctions are associated with legal control and may be:

| (a) | repressive/punitive, for example the deprivation of life or liberty; |

| (b) | restitutive, including damages, compensation and an apology, which aim to restore the status quo; or |

| (c) | regulatory, which aim to achieve compliance with a legal-administrative regime via such sanctions as the denial or forfeiture of licences, orders to cease or desist from acting in a proscribed manner or, in the case of immigration law, deportation. |

From a structural functionalist viewpoint, law is an integrative mechanism; it aims to control illegal activity, including crime, thereby restoring social equilibrium (Parsons, 1962: 58). There is a sense that laws reflect some level of social consensus that is important for social order. Until recently, sociologists concerned with social control were less interested with the formal means of social control than with its informal norms and processes of socialization, thus paying less attention to the phenomenon of law (Coser, 1982: 14; Ross, 1896: 518–22). Social control theorists concentrated on classifying the forms of social control, recognizing law as one of these forms but identifying distinctions between them. Law was of interest as a manifestation of larger social processes, rather than a topic of inquiry per se. This approach presents all forms of social control as constituting a continuum from informal to institutionalized forms, with law the most formal or specialized. It also tends to stress the normative character of law and emphasize the relationship between societal values and legal rules, which embody the most widely diffused and shared social values (Hunt, 1978: 145–7). In this paradigm, law is the key to achieving order and stability in complex societies where there are few shared interests (Hunt, 1978: 19–22).

However, law has coercive elements and is applied despite the absence of consensus. Weber’s emphasis on the relationship between law and domination enables an exploration of the coercive dimensions of law without ignoring its normative character (Hunt, 1993: 42–3; see Chapter 2). More critical theorists argue that law is oppressive, reflects or reinforces the interests of dominant segments of society and is used to control those whose interests and activities are defined as contrary to those of law makers. It is important not to reduce law to coercion but to examine the relationship between coercion and legitimacy (Hunt, 1978: 147).

Legal and nonlegal control

Considerable research, especially anthropological, has been devoted to distinguishing legal from nonlegal social control, specifying the relationships between the two and identifying those social conditions where one form of control predominates. Informal sanctions are adequate where little individualism or privacy exists, strong primary relationships prevail and the community or extended family retains primary authority. A comparison of two Mexican communities finds that the one where marital conflicts were settled in courts had experienced rapid population growth through migration, thus increasing heterogeneity. The family of origin’s ability to an influence their married children was weakened by the fact that their share of an inheritance had already been distributed at the time of marriage and married children formed their own households. In the other community, conflicts between spouses and censuring of their actions were usually mediated by senior family members and rarely in the town courts. It was smaller, with a more stable population, inheritance began at marriage and continued intermittently until the death of the parents, and the majority of couples lived near, if not within, the house of the husband’s father (Nader and Metzger, 1963: 589–91).

Black (1976, 1993) seeks to articulate the relationship between legal and nonlegal social control without reference to individual motivations, values, intentions or perceptions. He defines law as governmental social control, or ‘the normative life of a state and its citizens, such as legislation, litigation and adjudication’ (Black, 1976: 2; 1993: 3) and formulates propositions that seek to explain the quantity and style of law in every setting. According to Black, many societies have been anarchic (that is, without law), which does not mean that they were disorganized or lacked social control, but that the type of social control was not ‘legal’.

A complaint to a legal official … is more law than no complaint, whether it is a call to the police, a visit to a regulatory agency, or a lawsuit. … In criminal matters, an arrest is more law than no arrest, and so is a search or an interrogation. An indictment is more law than none, as is a prosecution, and a serious charge is more than a minor charge. (Black, 1976: 3)

The style of law – namely penal, compensatory, therapeutic or conciliatory – also varies; each style has its own way of defining deviant behaviour, each responds in its own way and has its own language and logic. Regarding the fundamental proposition, the question emerges: why do some situations have more law than others? The only response is that they have relatively less nonlegal social control, a tautology that explains nothing. Black avoids formulating any causal relationships and only asserts connections between variables (Greenberg, 1983: 338–48; Sciulli, 1995: 823–8). The theory conflates correlation with causation, rendering it ‘nothing more and nothing less than the attempt to systematize “commonsense”’ (Hunt, 1983: 20).

Empirical assessment of Black’s propositions is mixed. Generally, research regarding victims’ and others’ mobilization of law is not supportive (Doyle and Luckenbill, 1991; Gottfredson and Hindelang, 1979b; Lessan and Sheley, 1992; Mooney, 1986). A study of the mobilization of officials in dealing with various neighbourhood problems (including crime) found a weak or insignificant relationship between the quantity of law and stratification, morphology, culture and organization (Doyle and Luckenbill, 1991: 112). Alternative forms of social control and dispute resolution – talking with the person involved or getting together with neighbours – are positively not inversely related to the mobilization of law. Instead, the seriousness of an offence is an important dimension affecting a victim’s decision to inform the police and thereby to invoke a legal response. An adequate theory of the behaviour of criminal law must incorporate a proposition stating that the quantity of criminal law varies directly with the seriousness of the infraction as indicated by harm to the victim, which involves a subjective assessment, but this is explicitly excluded by Black’s framework, which does not consider individuals’ motivation or conduct (Gottfredson and Hindelang, 1979a: 16–17). In support of Black’s propositions, Kruttschnitt indicates that for most of the offences she examined involving female defendants, the legal system exerts less control over women who rely on others for day-to-day existence compared with those who are financially independent. Economic dependence entails a concomitant quantity of social control that is inversely related to the probability of more severe penal sanctions for women offenders (1982: 497–8). Nevertheless, it is not clear the extent to which Black’s propositions are gender specific, and he certainly would not claim that they are.

The criminal justice system

The police are the primary gatekeepers of the criminal justice system. Their role is to investigate crime and, in some jurisdictions, to prosecute criminal cases. Police deal with most so-called ordinary or common crimes, including driving offences, theft, drug offences, assault, robbery, homicide and rape. Most police work is reactive rather than proactive, with police relying heavily on citizens to initiate complaints and to report suspected crime (Black, 1970: 735). Other statutory agencies will investigate and often prosecute such corporate crimes as tax fraud and securities violations, as well as organized crime, including drug importation and trafficking, corruption and money laundering. These agencies tend to be more proactive in their investigatory functions.

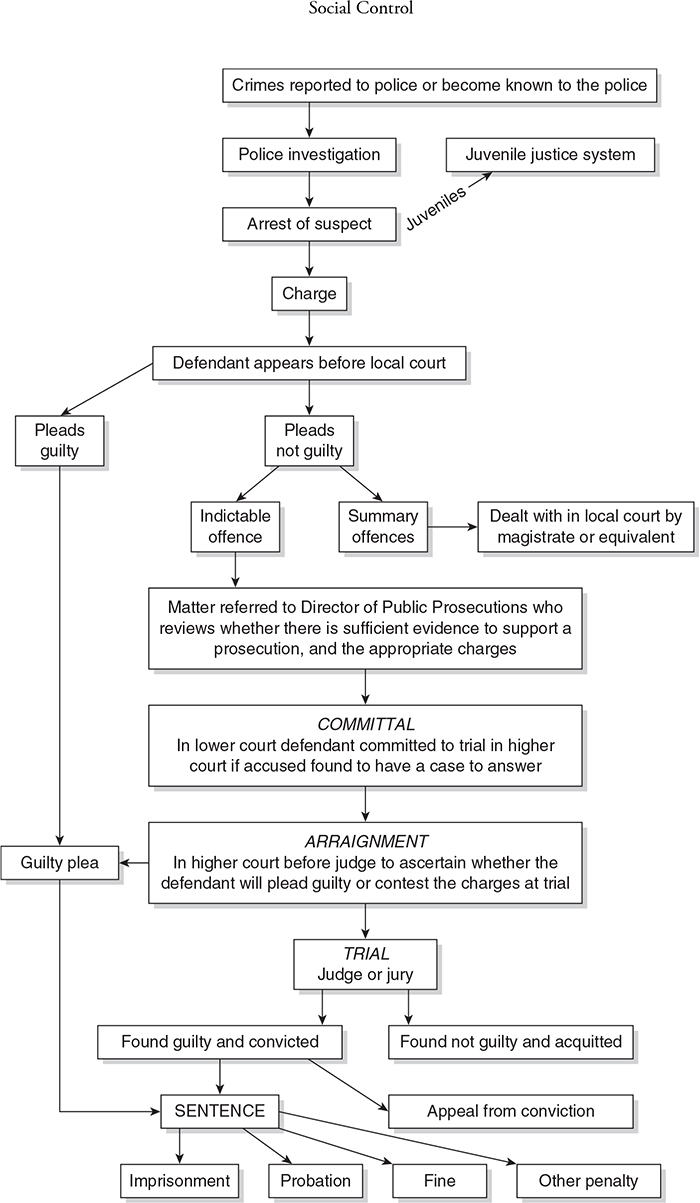

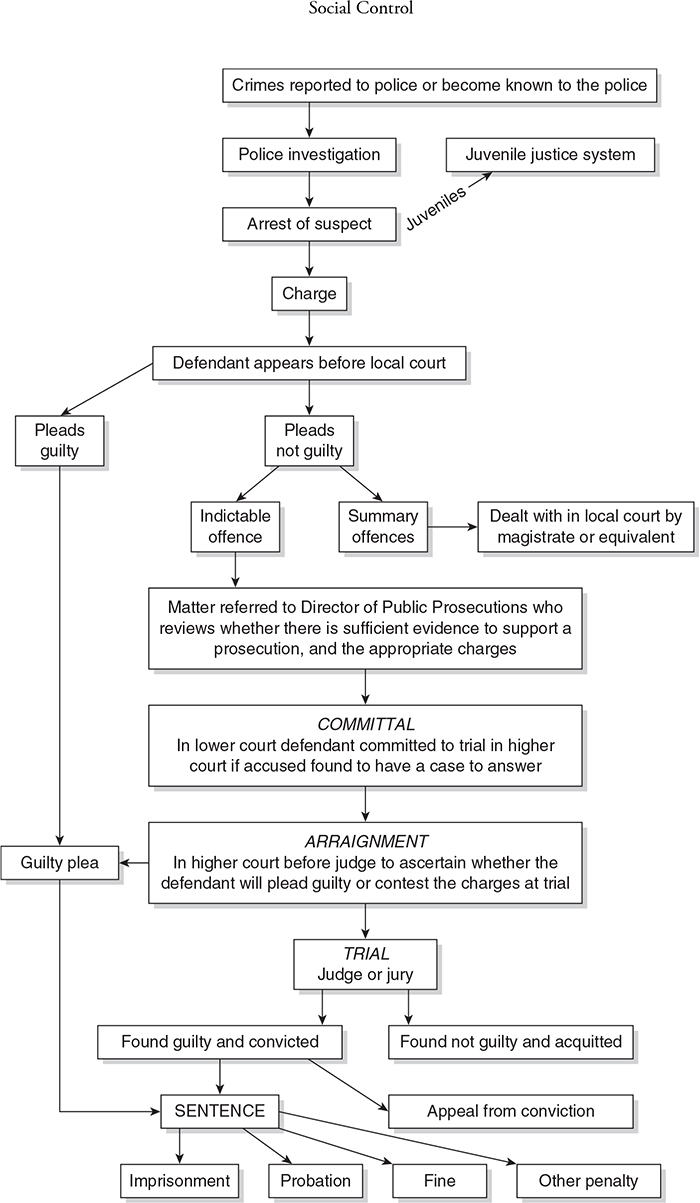

The criminal justice system comprises a number of crime-processing stages; the number of people receiving criminal sanctions is far fewer than the number coming into contact with the police. While each jurisdiction varies in the procedures adopted, Figure 6.1 provides a general overview of the kinds of processing stages involved.

At the outset, a suspected, alleged or actual crime is reported or becomes known to the police: they decide whether to ignore the complaint or initiate an investigation. An investigation may identify any suspected offender(s), whom the police may arrest and charge. If suspects are juveniles, they are ordinarily referred to the juvenile justice system. After charges are laid, a defendant appears before the first instance (local, magistrates or other lower) court where he or she enters a plea of guilty or not guilty. If the defendant pleads guilty, there is no trial and the defendant might be sentenced immediately or a date for sentencing will be fixed. A plea of not guilty to summary (less serious or minor) offences will be dealt with by the lower court, but if the offences are indictable (more serious or major) then these are typically referred on to the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP). The next stage involves the committal (though not all jurisdictions have this stage), where in Australia a magistrate determines whether or not the accused has a case to answer; if so, then they will be arraigned in a higher court and required to decide whether to plead guilty or to contest the charges at trial, which might be by judge alone or by jury. At the conclusion of a trial, the accused is found guilty and sentenced or is found not guilty and acquitted.

Figure 6.1 The Criminal Justice System

The criminal trial

A criminal trial aims to determine whether someone charged with any offence(s) is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. In common-law systems, the trial is an adversarial process where the prosecution and defence counsel will present their competing evidence, witnesses and arguments. Unlike civil-law legal systems, there is little scope for the judge to make independent inquiry or to test the evidence directly by interrogating witnesses or their lawyers. Less serious offences are usually tried in lower courts, sometimes called local or magistrates courts, by the judge alone. Such offences as murder, rape and armed robbery are normally tried by juries in higher courts, which means that the determination of guilt or otherwise is made by 12 members of the community. Recurrent debates focus on the capacity of jury members to assess legal argument and evidence impartially, especially where sophisticated expert evidence is tendered, and on the time involved in jury selection and deliberations (Mungham and Bankowski, 1976: 210–17). In jury trials, the role of the judge is adjudicatory: to ensure that the conduct of the case accords with the law and that any legal ambiguities are clarified for the jury. However, the judge sums up the trial for the jury by providing directions that can influence the jury’s actual decision regarding the guilt or innocence of the accused person.

After trial, if the defendant is found guilty, the judge determines the sentence in light of any statutory guidelines, including mandatory sentences, or with regard to judicially established sentencing tariffs or guidelines. While the assessment of guilt, or otherwise, by a public trial is held out as the pinnacle of criminal justice systems derived from English legal institutions, it is in fact more unusual than usual. Most criminal defendants will plead guilty and there will be no trial. In the USA, around nine out of ten felony convictions are obtained through guilty pleas rather than by trial (Padgett, 1985: 753). In England, around 90 per cent of cases in the magistrates’ courts and more than 60 per cent of cases in the crown court do not go to trial because a guilty plea has been entered (Zander, 1989: 188). The same pattern exists in Australia (Mack and Roach Anleu, 1995: 4). This discrepancy between the institutional framework emphasizing jury trials and the conditions under which most defendants plead guilty, especially if they initially plead not guilty but change their plea just before their trial, is a topic of widespread research and commentary.

Plea bargaining and negotiations are the subject of enormous academic controversy, research and policy debate, with considerable ambiguity about what is being discussed. The term plea bargaining conjures up images that critics view as antithetical to the justice system. On the one side, there are concerns that the defendant is enticed, or coerced, by their lawyer into pleading guilty, thus deviating from a central legal principle that guilty pleas must be free and voluntary (Alschuler, 1975: 1313). The incentives offered combined with the uncertainties of a trial create unacceptable inducements for innocent defendants to plead guilty. Defendants with few financial or cultural resources may be subject to stronger coercion, thereby reproducing social inequalities. Schulhofer suggests that the conscription of unwilling lawyers, low remuneration and heavy caseloads within public defender or legal aid offices place lawyers for the indigent under powerful pressure to resolve cases quickly without going to trial, whether or not such a disposition is in the best interests of their clients (Schulhofer, 1984: 138). Other critics maintain that guilty individuals avoid appropriate punishment because they are able to strike a deal with the prosecution or the sentencing judge, leaving the victims of crime and law-and-order advocates cynical about the justice process. They presume that any sentence will be more lenient than one following a trial and the fact that discussions are informally conducted in private jeopardizes wider public interest and accountability (McCoy, 1993: xiv–xv, 67, 190–1).

Four principal types of plea bargain or exchange are identifiable (Padgett, 1985: 75–8):

- Implicit plea bargaining, where the defendant pleads guilty to the original charge and expects a sentence discount for not taking up the court’s time. There is no actual bargaining or negotiation, but defendants perceive that they will be better off if they plead guilty (Friedman, 1979: 253; Heumann, 1975: 52–7). Defendants plead guilty both because they anticipate a lower sentence and because trial outcomes can be unpredictable and involve a greater risk of high or even maximum statutory penalties (Padgett, 1985: 761). In some jurisdictions the existence of sentence discounts is formalized in appellate judgements or by statute and thus these are not the creation of individual sentencing judges (Zdenkowski, 1994: 171–3).

- Charge reduction, where the prosecutor reduces the number or alters the type of charges to which a defendant agrees to plead guilty. It is assumed that reduced charges will translate into a reduced penalty.

- Sentence recommendation involves the prosecution recommending a particular disposition to the judge, who usually imposes the recommended sentence following the plea of guilty.

- Judicial plea bargaining occurs where a judge, after consulting with the defence and prosecution lawyers, offers the defendant a specific sentence if he or she agrees to plead guilty. Such consultations can occur informally in the judge’s chambers or formally, for example in the Sentence Indication Schemes trialed in some jurisdictions (Zdenkowski, 1994: 175–6).

At least some of these practices appear to be commonplace, even though the inevitability or necessity of plea bargaining is often questioned (Schulhofer, 1985: 570–91). In the USA, plea bargaining emerged as a significant practice after the Civil War, thereby reversing the common law’s discouragement of confessions and guilty pleas. Only 15 per cent of all felony convictions in Manhattan and Brooklyn were by guilty plea in 1839; in 1926 this figure had increased to 90 per cent, where it has remained, more or less (Alschuler, 1979: 223). By the end of the nineteenth century, plea bargaining had become the dominant way of resolving criminal cases, although it was only given US Supreme Court validity in 1970.

Until the late 1970s in England there was little interest in the subject of guilty plea negotiation, reflecting an assumption that the scope for plea bargaining had all but been eliminated, especially in the light of official and explicit condemnation (R v Turner 1970). Nevertheless, research into late guilty pleas and situations where defendants appeared to change their minds abruptly and decided to plead guilty reveals widespread informal plea negotiation, with most defendants experiencing pressures calculated to induce them to plead guilty (Baldwin and McConville, 1979: 27). Many of the 121 defendants interviewed in Birmingham said that in return for pleading guilty, their barrister had been able to obtain an undertaking from the judge or the prosecution and as a direct result an offer was made that they then accepted (Baldwin and McConville, 1977: 27). Such undertakings include explicit indications from the judge regarding the sentence. This contravenes case-law guidelines that permit the defence and prosecution counsel to discuss a case with the judge, who ‘should never indicate the sentence which he [sic] is minded to impose. … This could be taken to be undue pressure on the accused, thus depriving him [sic] of that complete freedom of choice which is essential’ (R v Turner 1970: 327). Defendants often felt coerced into pleading guilty or were presented with no alternative by their barristers (Baldwin and McConville, 1977: 46–56; 1979: 296).

In Australia, informal discussions between defence and prosecution lawyers dealing with the charges to be laid and the facts of the case occur every day. The negotiations are informal, relying on the trust and reciprocity of participants, and rarely involve discussions with a judge in chambers (Mack and Roach Anleu, 1995: 17–42). While participants will often use the language of bargaining or striking a deal, there is a strong belief that there is no plea bargaining as is understood to exist in the USA. There is a perception that because the judge is not involved, and as defence lawyers always maintain that they are acting on their client’s instructions, the potential for coercion and corruption is not common in Australia. Participants view these negotiations as a process of identifying the correct outcome and circumventing the need for a trial. They view the system as self-regulating, or self-correcting. There is a widespread belief that the police opt for more serious charges, not necessarily intentionally or out of mala fides, but because of a lack of legal training, police culture and ambit claims. Thus, discussions between defence and prosecution lawyers will correct the charges to be laid. They also suggest that, once a defendant has reached this point in the criminal justice system, they are guilty of something; the task of the prosecution and defence discussions is to identify exactly what offence this is (Mack and Roach Anleu, 1995: 44–9).

Why do plea discussions/bargains occur?

Much research is preoccupied with identifying the causes of plea discussions and specifying the conditions under which different forms of discussion prevail. Central themes include administrative capacity; substantive justice; the strength of the prosecution case; the organization of work and occupational relationships in the criminal justice system; and reducing uncertainty.

Administrative capacity Plea bargaining emerges in response to large caseloads that make it impossible for courts to deal with all cases. The most trenchant criticism of plea bargaining is that justice is being compromised or even substituted by organizational and managerial imperatives. Nevertheless, the relationship between caseloads and plea discussions is ambiguous (Nardulli, 1979: 89–91). Padgett (1990: 444) found that the massive criminal caseload during Prohibition in the USA increased federal plea bargaining in those districts with high caseload pressures. Judges responded by intensifying sentence discounting within a preexisting implicit plea-bargaining framework, rather than by altering the form of plea bargaining by becoming directly involved.

Attempts to eradicate plea bargaining may increase court caseloads and place pressure on the judiciary to participate in negotiations, both to ease the caseload burden and to provide a more appropriate outcome for the defendant. A strict prosecutorial policy in a Midwest US community forbidding charge reduction plea bargaining in drug-sale cases increased contested trials and the backlog of criminal cases. Many judges responded by encouraging pleas through personal participation in sentence-bargaining procedures. They did this via a pre-plea sentence commitment regarding a hypothetical situation, rather than an explicit granting of a sentence in the individual circumstances, thus retaining the fiction that judges were not part of explicit plea bargains in those cases in which the prosecutor’s policy did not allow charge reductions following plea negotiations (Church, 1976: 386–7). It appears that when a prosecutor cannot make concessions and the judge will not, then defendants are less likely to plead guilty (Church, 1976: 399). Similarly, in the Texas district courts, a 1975 prosecutorial ban on explicit plea bargaining in felony cases caused an immediate increase in the level of jury trials and a gradual decline in the disposition rate. Although most felony cases still involved guilty pleas, the ban affected the courts’ ability to move the felony docket efficiently, suggesting that explicit prosecutorial plea bargaining helps the administration of justice (Holmes et al., 1992: 1534). In Michigan, a prosecutorial prohibition on plea bargaining in cases where the law warranted a mandatory sentence, namely an additional two-year prison term if the defendant possessed a firearm while committing a felony, did not alter sentencing patterns significantly. In many serious cases, judges reduced the sentence for the primary offence to accommodate the additional two-year mandatory penalty. Following the bans on plea bargaining, sentence bargaining became common and replaced charge bargaining (Heumann and Loftin, 1979: 416–25). In contrast, the 1975 Alaska ban on charge and sentence negotiations in all crimes seems to have reduced explicit plea bargaining substantially without increasing implicit bargaining or the number of contested trials (Rubinstein and White, 1979: 369–74).

McCoy demonstrates how a 1982 Californian law restricting plea bargaining in serious felony cases actually shifted bargaining to the lower courts but did not ban it (1993: 37–8). Legislators presented this legislation – the Victims’ Bill of Rights – to the public as a ban on plea bargaining, which would thereby incorporate victims’ interests and concerns, given that a major criticism of plea bargaining is the exclusion of victims from the criminal justice process. Nonetheless, the bulk of the bill did not relate to victim participation and dealt with the right to be assured safe schools, the use of evidence that had previously been excluded for constitutional reasons and changes in the substantive rules of sentencing (McCoy, 1993: 28–9). The legislation contained major loopholes, including exceptions to the prohibition, which allowed plea bargaining to persist. It only limited plea bargaining in the superior court, leaving it unrestricted in the municipal court where almost every felony initially appeared and which became the primary forum for plea bargaining in serious cases. This loophole allowed court professionals to continue plea bargaining despite the restrictions. Consequently, more serious felony cases were concluded through guilty pleas prior to proper investigation or full evidentiary review and, paradoxically, by encouraging guilty pleas at earlier stages of the prosecution process, the new law actually strengthened rather than eliminated plea bargaining (McCoy, 1993: 37–8, 79–82, 178–84).

The increasing length of trials and complex rules of evidence also expand the volume of court work (Padgett, 1985: 762). Before the middle of the eighteenth century, the jury trial was a summary proceeding and it seems that between 12 and 20 felony cases could be tried every day. Trials were expeditious because neither prosecution nor defence were represented by lawyers in ordinary criminal trials, the defendant had fewer legal rights or privileges, the common law of evidence was virtually nonexistent, and there were few appeals (Langbein, 1979: 262–5). Now, criminal trials can take several days or even months, especially in corporate crime cases (Aronson, 1992).

Substantive justice Plea discussions attempt to achieve the correct outcome as defence and prosecution lawyers, unfettered by formal court procedures, are able to discuss issues freely. One aim is to substitute flexible sentencing standards that remain sensitive to the individual defendant (in terms of background and perceived criminality), for the harsher provisions of criminal codes, especially for offences where there are mandatory penalties or narrow sentencing guidelines that restrict judicial discretion. Legal practitioners will often justify their participation in plea negotiation as enabling the best and fairest outcome for everyone. Discussions facilitate the identification of the correct or appropriate offence; the defendant avoids a trial; the victim will not have to provide oral evidence or be subject to cross-examination; and the court time is saved (Mack, 1995: 42–9; Mulcahy, 1994: 421–3).

Negotiated pleas provide a degree of certainty that is absent in cases that go to trial. From the point of view of the defendant, the greatest uncertainty (perhaps even greater than conviction) relates to the type of penalty. While in most types of plea negotiation there is no guarantee of actual sentence, it is expected that a change or reduction in the original charges will result in a lesser penalty. For the prosecutor, uncertainty arises especially where there is a reliance on oral testimony and questions about how the witnesses will perform, particularly under cross-examination, or even about whether they will appear (Mulcahy, 1994: 420).

Organizational relationships