Shipping Finance and International Capital Markets

Chapter 28

Shipping Finance and International Capital Markets

1. Introduction

This chapter discusses key issues in modern shipping finance and explores the growing role of global capital markets in fund-raising for investment projects of shipping firms. We critically assess the attractiveness and efficiency of international equity and bond markets in particular, as important ship financing mechanisms that offer funding opportunities distinctive from traditional bank lending.

The structure of the chapter is as follows. Section 2 discusses the financial decisions in shipping and the implications of the capital structure mix for the financial performance of the firm. The major phases in modern ship finance are summarised and the dynamic role of global capital markets in shipping finance is assessed. Section 3 examines in details the function of equity markets as a financing mechanism, discusses the pricing of equity issues, analyses the risk return and volatility profile of shipping stocks and concludes with a brief presentation of alternative hybrid financing instruments. Section 4 covers the role and functions of bond markets with a focus on shipping bond credit rating and probability of default. Section 5 contributes a note on the important issue of efficient corporate governance mechanisms, emphasising on implications for shipping firms. Section 6 concludes.

2. Financial Decisions in Shipping

2.1 Strategic finance dynamics

An important shift has been seen recently in shipping finance instruments. International capital markets, predominantly equity and bond markets, have gradually gained a growing share in fund-raising for shipping firms (Syriopoulos, 2007). The capital intensity and magnitude of shipping investments requires capital availability at reasonable cost, but also careful project selection, based on a solid capital budgeting framework (Cullinane and Panayides, 2000). In a highly dynamic and volatile business environment, modern shipping finance becomes highly sophisticated, innovative and complex.

Shipping is a cyclical industry with idiosyncratic characteristics, highly leveraged assets, active second hand market and an estimated average ROA at 10% (Veraros, 2008). Market timing is critical to shipping investment decisions that bear high levels of risk and uncertainty. The behavioural pattern of shipping business is related to a number of factors, including, predominantly, the derived nature of shipping demand being sensitive to economic growth and trade, cyclicality in freight rates and vessel prices, demand and supply imbalances and fragmented business structure. The issue of optimal capital structure mix and the appropriate funding method is critical for an industry that is capital intensive and its operation employs real assets (vessels) of high commercial value.

Strategic decision making in shipping firms gradually shifts from simple profit maximisation to corporate value enhancement. To attain this, shipping firms require a selection of investment plans that bear growth potential and produce positive returns higher than the respective cost of capital employed. Intensified competition and tighten margins in the shipping markets have led companies to constantly pursue managerial efficiency, operational flexibility, and robust financial liquidity. A shipping company can attain business growth by following either an internal or external course of development. Subject to freight market conditions, shipping firms can expand their fleet by building new assets or purchasing second hand vessels. On the other hand, mergers, acquisitions and strategic alliances can be an alternative external growth path. In any case, these corporate growth strategies, combined with replacement requirements of ageing fleets, require substantial capital funding and careful financial planning.

As shipping companies adjust to a dynamic and rapidly changing environment so do the financial methods and instruments available to funding their investments. Convenient, cheap and timely access to capital financing is a prerequisite for a flexible capital structure mix, competitiveness, undisturbed operation and sustainable growth, particularly for shipping business. Two broad approaches in fund raising can be distinguished: (1) self-sustained or internal funding, by own (shareholder) equity finance; and (2) external funding, by debt finance (borrowing). Increases in own equity are based on corporate profitability and robust retained earnings sufficient to finance prospective investment projects. This source of funding is directly affected by the dividend policy of the firm that defines profit share distribution to shareholders, albeit at the expense of potential reinvestment decisions. As to external financing, shipping firms can alternatively turn towards international capital markets in order to raise investment funding. Debt financing may come from bank lending of wide variety and sophistication (bank mortgages, leasing, mezzanine finance, securitisation). In fact, this has been the prevailing and dominant source of ship funding over the years. Alternatively, shipping firms can turn into international debt markets to issue corporate bond securities or commercial paper. Furthermore, global equity markets can enhance own equity funding by issues of Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) or Seasoned Equity Offerings (SEOs).

The role of capital markets is critical for the promotion of shipping business growth and the creation of corporate value, since capital markets perform the following fundamental functions. As ‘primary’ markets, capital markets act as intermediaries to provide the funds required to financing new investment projects and sustain business growth. Fresh funds are channelled to firms in need through the issuance of securities. Furthermore, as ‘secondary’ markets, capital markets provide an efficient mechanism for valuation and trading of outstanding equity and bond securities. Growth potentials then of the underlying shipping firm (issuer) are reflected on the price movements of the issued securities, signalling investors’ perception of the firm’s value creation prospects.

Despite the marginal participation of international capital markets in ship finance for a number of years, some revitalisation is seen in public equity and bond issues more recently, on top of dominant bank lending. However, the recent global financial crisis, escalated since mid-2008, may affect shipping firms’ priorities as to their sources of capital funding. This is related to the fact that this unprecedented crisis and the induced economic recessionary phase directly involve the international banking system as a cause of the problem rather than simply as a victim of it. Combined with pressures imposed by a much more demanding disciplinary framework, such as the Basel II Accord and governmental supervisory constraints, bank lending is expected to become more careful, selective, conservative (relative to commercial risks undertaken) and, ultimately, scarce.

2.2 Capital structure and financial performance

A company can obtain long-term financing in the form of equity (issuing shares), debt (borrowing), retained profits or some combination. There is a fundamental distinction between equity and debt as sources of capital: equity refers to firm’s own funding by its shareholders and shares correspond to ownership rights. Debt, on the other hand, implies a core liability the firm has to meet over a plausible time horizon. A fundamental financial decision then relates to which of the two major fund raising approaches or mix should the firm prefer to finance its investment projects. The relative proportion of debt, equity and other outstanding securities constitutes the firm’s capital structure.

When corporations raise new funds from outside investors, they must choose which type of security to issue. The most common choice is financing through equity alone or through a combination of debt and equity. Whatever the firm’s choice, this affects the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) and has critical implications for the firm’s ROE and risk. The firm can attain growth and enhance corporate value only in case it undertakes investment projects that produce returns higher than their cost of capital funding. An incorrect financing decision may result in many forms of higher direct or indirect costs, such as higher cost of capital, lower stock price and lost growth opportunities, increased probability of bankruptcy, higher agency cost and possible wealth transfers from one group of investors to another.

The seminal Modigliani-Miller (MM) theorem on the ‘capital structure irrelevance principle’ has been the cornerstone of the firm’s capital structure decisions in perfect markets (Modigliani and Miller, 1958). According to the MM theorem, in an efficient market that follows a certain price process (random walk), in the absence of taxes, bankruptcy costs and asymmetric information, the value of a firm is unaffected by how that firm is financed. It does not matter if the firm’s capital is raised by issuing stock or selling debt or what the firm’s dividend policy is. In other words, the market value of a firm is determined by its earning power and the risk of its underlying assets and is independent of the way it chooses to finance its investments or distribute dividends (Pagano, 2005). However, as a firm’s debt increases, critics of the MM theorem argue, the increased risk of bankruptcy is ignored, though it can be substantial. Bankruptcy costs have two components: (1) the probability of financial distress; and, (2) the costs that would be incurred given that financial distress occurs. This relates to the ‘trade-off theory of leverage’ in which firms trade off the benefits of debt financing (favourable corporate tax treatment) against higher interest rates and bankruptcy costs. In practice, managers often have better information than outside investors, implying asymmetric (and not symmetric) information effects. Financing decisions then indicate some signalling to market participants about the firm’s prospects, according to the ‘signalling theory’. For instance, the announcement of a stock offering is generally taken as a signal that the firm’s prospects, as seen by its management, are not bright. A firm with positive prospects would try to avoid selling stock and seek to raise new capital by other sources instead; a debt offering is then taken as a positive signal. Issuing stock emits a negative signal, potentially depressing the stock price (even if the firm’s prospects are positive), so the firm should maintain a ‘reserve borrowing capacity’ to finance exceptional investment opportunities. This in turn implies that firms should, in normal times, use more equity and less debt than is suggested by the trade-off theory of leverage. However, the presence of flotation costs and asymmetric information may cause a firm to raise capital according to a ‘pecking order’. In this case, a firm first raises capital internally by reinvesting its net income and selling its short-term marketable securities. When that supply of funds has been exhausted, the firm will issue debt and perhaps preferred stock. The firm will only issue common stock as a last resort.

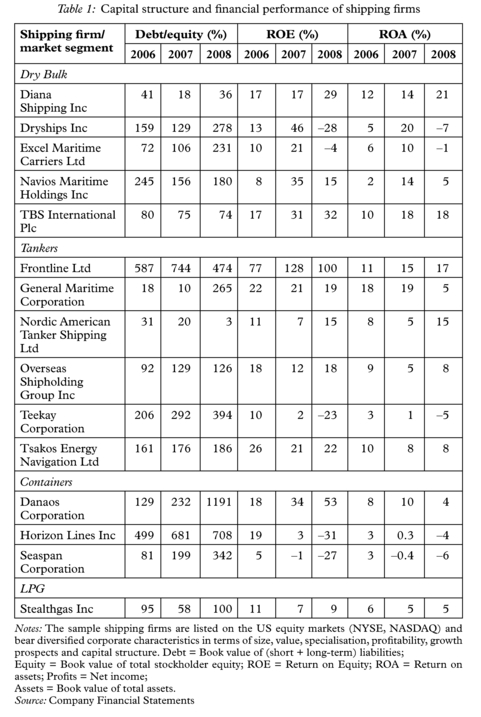

To conclude, the optimal capital structure for the firm is that which maximises corporate market value (the firm’s stock price). This generally calls for a debt ratio that is lower than the one that maximises expected earnings per share (EPS). As a brief illustration, Table 1 summarises the capital structure and financial performance of a diversified sample of shipping firms listed in the US equity markets (NYSE, NASDAQ), as they are depicted by the debt-equity ratio, Return on Equity (ROE) and Return on Assets (ROA). An anticipated, though striking, finding points to the extremely high debt/equity ratios for most of the shipping firms in the sample, albeit at diverging levels. This holds irrespective of the corresponding market segment and supports the view that shipping finance is heavily dependent on debt funding over time.

2.3 Major phases in modern shipping finance

During the last 30 years, international shipping markets have been moving through a volatile sequence of upward and downward swings but culminated in an extraordinary eight-year boom from 2001 to 2008. Over this period, daily earnings soared persistently from US $24,000 to US $50,000. Then, the global financial crisis and economic recession hit the world economy as well as the shipping markets. Freight earnings crashed down to a daily bottom of US $5,000 in (handymax) dry bulk markets before gradually adjust to US $8,500 by mid-2009, with many vessels though still earning less than operating costs. At the same time, the bulker fleet grew by a robust 10.8% rate and the balance in fundamentals worsened (Stopford, 2009, 2010). Diverging shipping demand and supply imbalances were already apparent in the 2007 figures; there were three times as many orders as deliveries (270 mln dwt vs 80 mln dwt). Based on end-2009 estimates the market value of a consolidated order book was standing at around US $300 bn, a figure which raises scepticism as to the recovery horizon of the shipping business. This gloomy international environment has captured shipping companies into unfolding capital investment programmes, abrupt earnings decline and excess tonnage

capacity, with an ailing global banking system under restructuring (Clarkson Research Services, 2009). This in turn raises market concerns about the critical adjustments required in shipping firms’ capital funding decisions and the most appropriate financing instruments for the time being.

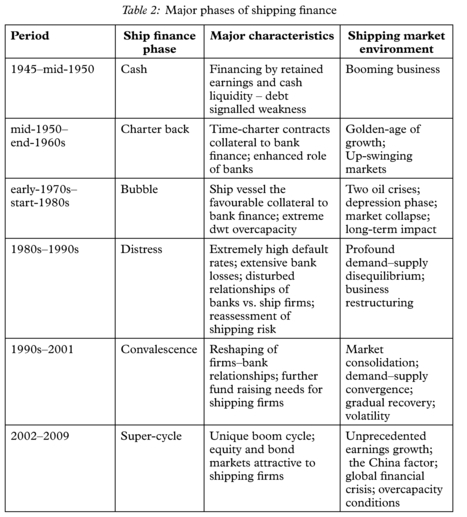

The methods, instruments and characteristics of ship finance are seen to change over time, adjusting accordingly to the prevailing economic, market and sectoral conditions. Five major phases in modern ship finance can be distinguished during 1950–2000, according to Stopford (2002); we expand this framework to add a recent, sixth, ship finance phase (see Table 2). These phases have been closely associated with shifts in shipping market fundamentals, predominantly international trade and fleet growth.

Source: Lloyd’s Shipping Economist (2005)

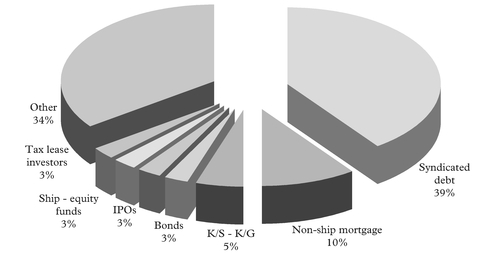

Furthermore, according to Lloyd’s estimates, the contribution of major capital funding sources to shipping is seen to diverge substantially over time (Matthews, 2005). ‘Debt financing’, predominantly bank loans, continues accounting for the largest share of shipping finance. Over the last decade, the annual volume of syndicated debt gradually five-folded, from US $2 bn to over US $10 bn. A broad source of funding, termed ‘other’, corresponds to more than one-third of the pie and incorporates diversified financing instruments, such as bilateral loans, shipyard credit, governmental contributions and internal equity finance. International capital markets are seen to gradually gain an active role in shipping finance. The respective shares of global equity markets (IPOs) and debt markets (bond issues) are estimated at 2–3% each. The K/S partnerships in Norway and particularly the KG companies in Germany are also considered critical financing vehicles in shipping business. The remaining capital share is associated with a variety of funding sources (see Figure 1).

2.4 The dynamic role of capital markets in shipping

Following a period of fast and robust growth rates, shipping markets collapsed in the fourth quarter of 2008. Freight earnings evaporated abruptly, as the global financial crisis escalated. In an environment of severe adjustments in the banking sector, liquidity constraints and overcapacity conditions, shipping market players have been wondering what their next steps should be. Fundamental questions, as to whether to expand business operations, consolidate with a competitor or proceed to asset liquidation and exit the market, remain unanswered. These strategic decisions are examined against a consolidated order book of an estimated contract value exceeding $300 bn (end-2009). This, nevertheless, remains an attractive capital pie for financiers, shipyards and brokers (Clarkson Research Services, 2009). In this setting of recessionary conditions, banking restructuring and freight market swings, a key question remains where all this funding will come from. A convenient and timely response to the question of capital fund raising has critical implications for shipping firms’ capital structure, cost of capital, cash flow liquidity, profitability and performance (ROA, ROE) and ultimately shareholder value. As has been invariably the case in past shipping market history, financial crises also imply entrepreneurial opportunities for prudent shipowners.

The shipping business consists of approximately 30,000 companies and is one of the most finance-intensive industries. Financing requirements per annum have been roughly estimated at US $80 bn for funding only new buildings (Goulielmos and Psifia, 2006). Traditional bank lending dominates ship finance over time, although some decline in its share has been recorded more recently at around 65%, in favour of alternative forms of financing (Petropoulos, 2009). Shipping finance techniques and instruments become more innovative and synthetic. An increasing number of shipping companies is seen to gradually switch towards international capital markets, to finance their ambitious investment projects by equity funding (stock markets) or debt issuing (bonds markets). Traditional and modern ship finance instruments can be distinguished into three broad classes: (1) equity finance: public funding (IPOs); seasoned equity offerings (SEOs); retained earnings (operations and sales), private equity funding; (2) debt finance: bank lending (wide variety and sophistication), corporate bond issues, specialised financial institutions, shipyard finance, private debt finance; (3) alternative finance: lease, mezzanine finance, securitisation, hybrid finance (Syriopoulos, 2007).

The year 2005 was declared ‘the year of the shipping IPOs’, as 12 new shipping firms raised more than US $4 bn in US equity market IPOs, most of them of Greek shipownership. In fact, from 2005–2007, Greek shipping companies alone raised total funds of about US $1.5 bn in the US markets. The renaissance of shipping IPO market was confirmed by a tenfold increase in the funds raised by the industry, according to Lloyd’s estimates. As market timing proved to be right, fund raising was further supported by freight rates sky-rocketed at record levels and international investors’ appetite for ‘fashionable’ shipping stocks. Investors, after all, remain in constant search of attractive investment opportunities and alternative style investments (Bernstein, 1995). This trend underlines an important shift not only in shipping finance decisions and the capital structure of the firm but in the corporate governance front as well. Shipping companies, previously private, family owned and managed, introverted, with no disclosure constraints were now being transformed into publicly listed, extrovert, multi-shareholder entities with ownership dilution and extensive disclosure responsibilities (Syriopoulos and Theotokas, 2007). These issues have considerable implications for the growth prospects of shipping firms as well as for the risk-return profile of the listed shipping stocks and can directly affect shareholder value and investors’ asset allocation decisions.

3. Equity Markets and Shipping IPOs

3.1 Shipping firms discover equity markets

Despite the fact that bank lending continues dominating shipping finance, a gradual shift in shipping firms’ funding attitudes has been apparent more recently in favour of international equity markets. This shift has been associated with the interactive impact of critical factors, including internationalisation and integration of global capital markets; deficiencies and consolidation of major banking players; emphasis on capital adequacy and ‘solvency ratios’ by banks, shipping firms and investors; liquidity constraints and erosion of firm capital reserves; substantial funding requirements to replace ageing fleets; structural and cultural adjustment of shipping firms, partly induced by capital market requirements and investors’ expectations; extrovert market approach and promotion of wider multi-shareholdership; market visibility and prestige towards institutional and private investors; emphasis on the concepts of corporate governance, social responsibility and business ethics.

Expanding on these issues, major advantages for shipping firms going public include: (i) access to capital markets that are not readily available to private companies; (ii) liquidity, at potentially higher valuations, if the company’s fundamental are compelling enough to attract new investors; (iii) stock options as a means to attract and retain key personnel; (iv) opportunities for companies to utilise their stock to acquire other companies. However, the long-term attractiveness of international equity markets for shipping companies will only be sustained in case freight and equity market performance remains robust and corporate profitability is less volatile.

Until 2004, equity markets had played only a marginal role in shipping finance, despite their prime role as an investment funding mechanism. From an investor’s point of view, historically, shipping stocks were not a particularly attractive choice for fund allocation but had a rather ‘negative’ reputation. This adverse attitude can partly be related to a series of shipping defaults in the 1990s, including, bank loans, high yield bonds and corporate bankruptcies. Other reasons include close family ownership ties, reluctance of shipowners to dilute company control, non-disclosure of sensitive company information and the unattractiveness of shipping stocks due to volatile earnings (Syriopoulos, 2007). Shipping companies only recently have discovered the virtues of public listing on international stock exchanges. The shipping IPO wave, during 2000–2007, has tackled investors’ appetite, as the latter also discover the attractiveness of exchange traded shipping firms. This trend has been supported by booming freight rates and strong balance sheets in an environment of bullish stock markets. Steady growth rates in the US economy and high growth rates in the Chinese economy, particularly during 2003–2007, led the shipping sector into a unique growth super-cycle during 2002–2008, generating strong earnings and cash flows.

Shipping IPOs are distinct from those of ordinary industrial or service companies. The market value of a shipping company is often closely associated with the underlying value of the physical assets (vessels). In this respect, shipping IPOs bear similarities with the respective IPOs of closed-end funds and property firms. Furthermore, due to extensive information flows in international vessel sales and purchase markets, shipping IPOs tend to exhibit lower information asymmetry. Due to the cyclical nature of shipping business, shipping firms tend to prefer listing on the equity markets whenever shipping market prospects appear to be robust.

3.2 Leading equity markets in shipping IPOs

In the 1980s, the universe of publicly listed shipping stocks was small and London was the principal equity market for shipping stocks. Apart from London, shipping stocks were also listed in the New York stock market. In the 1990s, Oslo took the top position in Europe as the leading stock exchange for shipping IPOs. Due to market shifts, London has gradually lost its leading role in shipping IPOs, partly due to companies going private or to mergers and acquisitions, such as the P&O acquisition by DP Ports World (Erdogan, 2005). In general, European equity markets have experienced declining trends in shipping market value from more than 1% in the early 1990s to 0.6% of total market value recently (Matthews, 2006). In the US equity markets, a series of de-mergers and spin-offs of shipping businesses led to the restructuring of the shipping sector. Shipping firms and investors have more recently switched towards a number of upcoming Asian stock markets that now attract shipping IPOs, including Hong Kong, Singapore, Bangkok and Taiwan.

The transportation sector, on aggregate, lags behind in global equity market values. The market capitalisation of global transportation companies increased substantially during the last 30 years. It reached a high of US $700 bn corresponding to a share of total market capitalisation of above 4% (end of 1980s), before declining to below 2% (2006). As a comparison, the oil and gas sector and the financial sector account for nearly 20% and 15% of global stock market capitalisation, respectively (Matthews, 2006). Against an estimated 8–9% of GDP in OECD countries, the low market share in capitalisation indicates that transportation remains persistently neglected in international stock markets. The shipping sector, in particular, has also seen a marginal capitalisation share at about 0.4% of global equity market value; liner shipping covers the largest share (Matthews, 2006). Despite the recent IPO activity, this figure reflects low shipping market participation, taking into account that the shipping sector is estimated at about 2% of world GDP. Only a limited number of about 30 shipping firms have been estimated to bear a market value of above US $1 bn, with A.P. Moller-Maersk Group, a Danish shipping conglomerate, the only firm accounting for about 20% (around US $30 bn) of total shipping stock market value globally (Syriopoulos, 2007).

More recently, the US stock markets (NYSE, NASDAQ) have seen some revitalised IPO activity, attracting jointly the largest number of shipping IPO issues and regaining their leading role as preferred equity markets to IPO launches. Oslo follows at a distance now, leaving London Stock Exchange behind (Merikas et al., 2009). Strong advantages of the US capital markets include fund-raising depth, reputable position in the investment community, improved share liquidity, reliable pricing, high corporate prestige and exposure to an international investor base. According to Clarkson’s data, there were about 170 shipping companies listed worldwide by 2006, corresponding to an estimated market value of US $210 bln, although pure shipping firms are only about half that number (Matthews, 2006). During the recent intensive IPO cycle (mid-2004 to end-2005), total shipping IPO value and secondary listings were estimated in excess of US $4 bln, whereas in the first half of 2006 alone, international shipping IPOs amounted to a value of more than US $100 bln (Matthews, 2006).

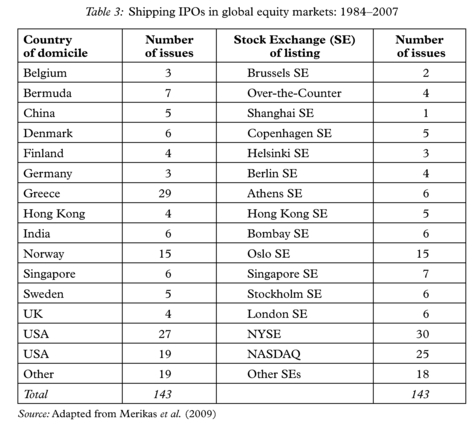

Table 3 presents a summary of major shipping IPO issues per country and per stock market, during 1984–2007. Over this time span, the US equity markets (NYSE, NASDAQ) confirm their leading position, as they have seen the largest IPO number (55 issues). The Oslo Stock Exchange enjoys persistently high levels of shipping IPO activity and follows with 15 IPOs but the London Stock Exchange (LSE) ranks lower (6 IPOs). Of these sample IPOs, only 38 firms were listed before 2000; most of these IPOs have come into equity markets after 2000, supporting the shift of shipping firms towards global equity markets, as discussed earlier.

Taking into account the leading role of the US markets and the upcoming Asian markets, European stock markets may see further declines in shipping market value.

Major reasons that explain the limited presence of the shipping sector in the European markets include the highly fragmented industry structure, the concentrated ownership (as founding families remain major shareholders), the large number of relatively small private companies, the decision of some public shipping companies to go private and the limited number of IPOs in Europe compared with the US.

3.3 Key issues in shipping IPOs

3.3.1 Models of IPO pricing

A company can be listed and traded on a Stock Exchange by issuing new shares. Whenever this share offering to investors takes place for the first time, it is known as an Initial Public Offering (IPO). The company ‘goes public’ and its shares can then be freely traded in the open equity market. The IPO price is the price at which the new shareholders buy the shares at issue. The initial return of an IPO relates to the difference between the equilibrium price following the issue and the IPO price. The IPO price is jointly decided by the underwriter and the listing firm at the end of the IPO procedure, according to financial analysts’ valuations and the demand expressed for the shares. The definitive offer price is generally lower than the first equilibrium price; this is well known under the term of ‘IPO underpricing’ (Ljungovist, 2005). The IPO motives, pricing, initial market appraisal and long-run performance have been the focus of a large theoretical and empirical financial literature.

Alternative theoretical approaches, such as the information asymmetry and signalling models or the life cycle and market-timing models, have been proposed to explain these issues (Ritter and Welch, 2002; Drobetz et al., 2005; Derrien and Kecskes, 2007). The primary motive as to ‘why do firms go public’ relates to their decision to raise equity capital and to create a public market in which the founders and other shareholders can convert part of the corporate value they possess into cash at a future date. In addition, being the first in an industry to go public sometimes confers a first-mover advantage, whereas IPOs allow more ownership dispersion with relevant advantages and disadvantages. Furthermore, by going public, entrepreneurs help facilitate the acquisition of their company for a higher value than what they would earn from an outright sale (Brau et al., 2002). Market timing is also important to IPO decisions. An IPO may be delayed, if a bear market phase can potentially result to a low firm value; whereas a bull market may offer more favourable pricing conditions (Lucas and McDonald, 1990). It has been also argued that larger companies and companies in industries with high market-to-book ratios are more likely to go public and companies going public seem to have reduced their costs of credit. IPO activity is affected by investor sentiment and follows high investment and growth, not vice versa (Pagano et al., 1998; Lowry, 2003). To recap, the evidence of large variation in the number of IPOs suggests that market conditions are the most important factor in the decision to go public. The other important factor seems to be the life cycle stage of the firm.

A large body of empirical studies documents a systematic price increase from the offer IPO price to the first-day closing price (‘IPO underpricing puzzle’). Ritter and Welch (2002), for instance, study a sample of 6,249 IPOs from 1980–2001 and estimate an average ‘first day’ return of 18.8%. Approximately 70% of the IPOs end the first trading day at a closing price greater than the offer price. This pattern of underpriced IPOs is seen to apply in different firms, sectors, markets and countries. A possible justification of the IPO ‘undepricing puzzle’ relates to reasons of asymmetric information between market participants, as IPO issuers are expected to be more informed than investors. Better quality issuers deliberately sell their shares at a lower price than the market believes they are worth, which deters lower quality issuers from following. These issuers can recoup their initial value sacrifice post-IPO, either in future issuing activity, favourable market responses to future dividend announcements or analyst coverage. In line with a body of signalling models, firms demonstrate that they are high quality by throwing money away; one way to do this is to leave money on the table in the IPO. Empirical evidence indicated that the relationship between IPO price and underpricing may be U-shaped, whereas in contrast, post-IPO turnover may display an inverted U-shaped relation to IPO price (Fernando et al., 2004). However, the conclusions produced on these issues remain rather mixed. Compared with the rich financial literature on a country level, the body of studies on individual sectors, especially shipping, remains thin.

The long-run stock price underperformance in the years after the IPO offering is another key topic of interest in IPO research (‘IPO long-run underperformance puzzle’). Measuring long-run performance can focus either on absolute (raw) performance, or relative performance (abnormal returns vs market benchmark). Empirical evidence indicates that IPOs underperform in the long run. A number of IPOs in the US, for instance, were seen to underperform significantly relative to non-issuing firms for three to five years after the listing date (Ritter, 1991; Loughran and Ritter, 1995). According to other estimates (Ritter and Welch, 2002), an investor who buys shares at the first-day closing price and holds them for an investment horizon of three years, would attaint IPO returns of 22.6%. However, compared to a market benchmark (CRSP value-weighted market index), the average IPO price underperforms by 23.4%. IPO long-run performance remains a controversial issue, sensitive to the empirical approach employed and directly dependent on the preferential theoretical stance of market efficiency or behavioural finance framework. Many studies have contributed international evidence on the long-term IPO underperformance consistent with what has been found for the US market, including Australia (Lee et al., 1996); Japan (Cai and Wei, 1997); Sweden (Brounen and Eichholtz, 2002); Germany (Jaskiewicz et al., 2005); United Kingdom (Goergen et al., 2006); France and Greece (Chahine, 2008). In a pan-European study, evidence of long-run underperformance has been documented for a sample of 15 countries, indicating long-term abnormal returns in Europe to be negative (Gajewski and Gresse, 2006).

3.3.2 Shipping IPO pricing

Capital markets can play a key role in promoting shipping business growth and value creation. They may act as an intermediary mechanism to provide funds required to finance new investment projects and sustain business growth. Fresh funds can be channelled to shipping firms in need through the issuance of new securities by an IPO process. As secondary markets, capital markets provide an efficient mechanism for trading outstanding securities. Following IPO market listing and trading, a shipping company has the privilege to regularly return to stock market investors and request additional funding through seasoned equity offerings (SEOs).

Major factors that contribute to corporate value creation, as reflected on the firm’s stock price upward behaviour, include, inter alia: robust fundamentals; efficient and well reputed management; high cash flows/earnings; realistic market valuations; M&A corporate stories; and growth potential. The positive behaviour of shipping stocks can be further enhanced by upward freight markets, bullish stock market trends and rich cash liquidity conditions. Nevertheless, private and institutional investors have remained sceptical for years about shipping firms’ stocks. This investors’ attitude has been adversely affected by ‘inward’ family organisation, structure and management; ship-owners’ reluctance to expand shareholder base; non-disclosure of critical corporate actions; low or no dividend yield; non-appealing risk-return trade-off; highly volatile freight markets, resulting to abnormal corporate earnings and highly risky investments.

A critical question relates to the motives driving shipping firms’ shift towards listing on international equity markets. In the past, the strict requirements of transparency and disclosure that listed companies should meet was a constraint for many shipping firms, especially at volatile market times and earnings fluctuations. However, this is seen to gradually change. Equity markets appear now to be an attractive choice for firms with stable income flows and growth potential. With interest rates remaining at low levels, banking finance may still appear to be a cheap funding alternative. However, a number of shipping companies have decided to go public recently and raise funds quickly (despite significant public listing costs), to take advantage of the robust freight markets and investors’ positive sentiment towards shipping stocks. Still, a number of shipping firms have experienced substantial market value losses, since freight markers moved downwards amidst conditions of global financial crisis and economic recession.

These developments are anticipated to have an adverse impact on cautious investors’ expectations, probably making it more difficult for shipping firms to raise financing from the equity markets in the near future. Good quality shipping IPOs can be successful, though there have been cases in the recent past that it was not always easy to sell shipping shares to investors. Despite the fact that investors’ sentiment may not remain as positive as it was earlier, fair IPO pricing, backed by robust earnings cash flow streams and stable freight markets, can conclude to successful shipping IPOs. A critical advantage of shipping firms’ listings is related to the fact that shipping is a real asset-backed business and certain risk levels can still be acceptable with some confidence by investors. The most risky bet appears to be on whether institutional and private investors will continue to consider shipping stocks as an attractive alternative ‘style’ investment class, hence, facilitating shipping firms’ funding (Syriopoulos and Roumpis, 2009).

The pricing of IPO equity issues remains a central issue for shipping firms interested in raising equity funding in global stock markets. Since the majority of shipping IPOs refers to bulk shipping offerings, the issuer will set an IPO price at or near market-adjusted net asset value (NAV) per share. This is reasonable in cases where company earnings and cash flows fully support NAV (Stokes, 1997). In practice, however, ship prices in the second-hand market do not necessarily reflect operating cash flow and earnings generated by the ships. More frequently, ship prices represent a very high multiple of operating cash flow, whereas in certain bulk shipping segments operating earnings were negative for a number of years.

Equity financing can be an attractive source of capital for shipping companies, taking into account the relatively lower implied cost of capital against other sources of funding. This is related to the fact that shipping companies traditionally pay low or no dividend to investors and investors accept this practice, since, due to the capital intensive nature of shipping business, retained earnings are channelled to fleet replacement and expansion. On the other hand, investors’ target of expected return on equity is set at high levels. Assuming that a shipping company can borrow at a spread over Libor (+1% to 2%), this can result to borrowing costs on senior debt of, say, 7%. Subordinate debt might cost 10–12% per annum, on a 10–year maturity. Investors, however, will typically seek a return on equity of 15–20% per annum, given the volatile freight markets and their risk exposure (Stokes, 1997). Taking into account that many shipping companies are rated below investment grade, this implies that they must attain return on equity well above average stock market returns to prevent their share price from declining.