Settling Islamic Finance Disputes: The Case of Malaysia and Saudi Arabia

Chapter 20

Settling Islamic Finance Disputes: The Case of Malaysia and Saudi Arabia

The Islamic banking and finance industry gained popularity during the late 1970s in Middle East countries. Following the public acceptance and robust development of the industry, several other players appeared, including Hong Kong, Malaysia, Pakistan, and Sudan. The industry developed quickly, attracting investors who were Muslim and non-Muslim, local and foreign, but disputes and misunderstandings were inevitable. The disputing parties had the option to resort to court litigation or out-of-court settlement.

Drawn from ongoing research, this chapter seeks to analyze the judicial system in two jurisdictions—Malaysia and Saudi Arabia—within the context of Islamic banking and finance disputes. The first section describes the background and constitutional frameworks of both countries, and the second section looks at the judicial structure entailing the hearing and settlement of Islamic finance disputes. The third part examines the independence of the courts, and the fourth part elaborates on selected cases of Islamic finance disputes. The chapter concludes by describing the similarities and differences of judicial systems in the two countries and by suggesting new directions for research in the area.

Background and the Constitutional Frameworks

Located in Southeast Asia, Malaysia had a population of 28.3 million in 2010, 60 percent of whom were Muslim (Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia 2011). It currently stands out as a developing nation with robust development and growth of international Islamic banking and financial markets. A number of studies have suggested that the growth rate of Islamic finance in Malaysia is impressive by any standards. Hence, Malaysia has the capacity to retain its leadership in global Islamic finance despite the emergence of competition from centers such as Hong Kong and Dubai (Yong 2007). Malaysia has a large number of diverse players and institutions in the Islamic financial system, which includes retail and commercial Islamic banking and finance, general and life takaful (the Islamic insurance concept), and Islamic capital markets. A growing range of products and services are being offered, as Malaysia’s banking and finance industry becomes competitive in product structure and pricing (Razak and Karim 2008). All these developments have increased the attractiveness of the Islamic financial instruments as an asset class for investments, drawing both Malaysian and foreign investors.

The federal constitution of Malaysia was adopted on August 31, 1957, the day Malaysia gained its independence from the British colonials. Article 3(1) of the constitution declares Islam as the official religion of the federation and guarantees religious freedom. The ninth schedule outlines the legislative lists, specifying federal, state, and common jurisdictional lists. Specifically for the Islamic finance industry, the government of Malaysia passed written legislation to accommodate the finance system’s growth in the country. For the banking and financial market, the relevant laws are the Central Bank of Malaysia Act 2009, the Islamic Banking Act 1983, and the Banking and Financial Institutions Act 1989.

The principal regulator of the Malaysian Islamic financial system, the Central Bank of Malaysia, has introduced a comprehensive legal framework for Islamic financial institutions. The Central Bank undertook several initiatives, including a 10-year master plan, an interbank Islamic money market, coverage by the Malaysian Deposit Insurance Corporation, a friendly tax regime, and incentives under the Malaysia International Financial Centre. These initiatives were designed to further enhance and develop the Islamic financial institutions in Malaysia and to allow the country to become an international hub for Islamic banking and insurance. The takaful market is also regulated by the Central Bank of Malaysia, and the primary legislation governing the market is the Takaful Act 1984.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is the Middle East’s largest state by land area, constituting the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and is the second-largest state in the Arab world after Algeria. As of July 2013, Saudi Arabia had an estimated population of 26.9 million, of which 5.6 million were noncitizens. The country encompasses approximately 2.15 million square kilometers (830,000 square miles).1 Saudi Arabia is an absolute monarchy, although according to the Basic Law of Saudi Arabia, which was adopted by royal decree in 1992, the king must comply with the Shari’a and the Holy Qur’an. The Qur’an and the Sunnah are declared to be the country’s constitution; no modern constitution has ever been written for Saudi Arabia (Cavendish 2007: 78).

The legal framework organizing the financial sector of Saudi Arabia could be classified into three groups of laws. The first group comprises the legal fundamentals for the political, social, and economic aspects of the nation; the monetary policies; the original laws of the Arab region; the money and currency control laws; and various commercial laws (Sabri 2009). The second group of laws concerns the organizing activities of financial institutions and includes commercial, specialized, and Islamic bank laws; central banks laws; insurance laws; insurance control laws; leasing financing laws; and social securities agencies and public provident fund laws. The third group of laws comprises the financial markets and includes corporate share laws, securities laws and trading regulations, government securities commission laws, stock exchange laws and bylaws, disclosure and reporting requirements, broker and membership requirements, insider trading laws, and regulations on price limits and margins.

Notably, Saudi Arabia has no formal codified constitution. In March 1992, King Fahd bin Adulaziz al Saud issued the governing law, or Basic Law, which articulates the government’s rights and responsibilities. It includes provisions declaring Islam as the official state religion and the Qur’an and Sunnah as the state constitution. The Basic Law provides that the state must protect the rights of the people in line with Shari’a, acknowledges the independence of the judiciary, and bases the administration of justice on the Shari’a rules according to the teachings of the Qur’an, the Sunnah, and the regulations set by the ruler, provided that they do not contradict the provisions of the Qur’an and the Sunnah. On the same notion, article 9 of the Basic Law states that “the family is the kernel of the Saudi society, and its members shall be brought up on the basis of the Islamic faith.” Furthermore, article 26 generally provides that the state protects human rights “in accordance with the Islamic Shari’a.”

The Dispute Resolution Structure

The dispute resolution system in Malaysia has two parts: the court litigation system and the alternative processes. The court system also has two parts: the Shari’a and the civil judicial systems. Under the Shari’a judicial system, even though Shari’a law provides regulations in all aspects, Shari’a law as it applies in Malaysia is confined to personal matters. The Shari’a courts’ jurisdiction covers only matters involving Muslims and deals only with specific personal civil matters. For instance, such matters may include matrimonial matters, matters concerning the administration of Islamic law in the state, land, waqf (donation of land, buildings, or money for religious or charitable purposes), zakat (a charitable tax payable by Muslims), and hibah (a form of voluntary interest payment), and state holidays.2 In criminal cases, the court can pass sentences of no more than three years’ imprisonment, fines of up to RM 5,000, and punishments of up to six strokes of the cane.3

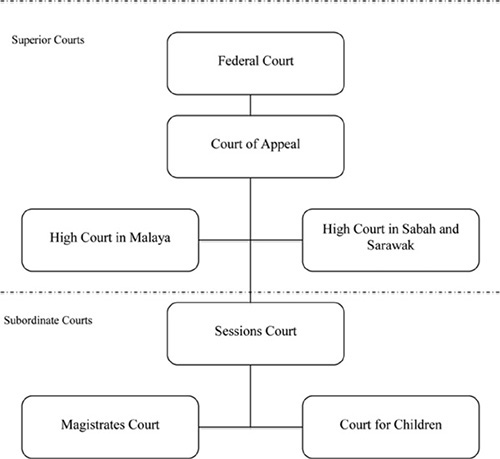

The administration of the Shari’a courts falls within the ambit of each state’s jurisdiction. Hence, there could be some differences in the civil and criminal jurisdictions of the courts from one state to another. Primarily, Shari’a courts are classified into three levels: the Shari’a Subordinate Court, which is the court of first instance, followed by the Shari’a High Court and the Shari’a Appeal Court. The latter court is the highest authority in Malaysia’s Shari’a judicial system in Malaysia (Figure 20.1).

Fig. 20.1 Structure of the Malaysian Shari’a courts

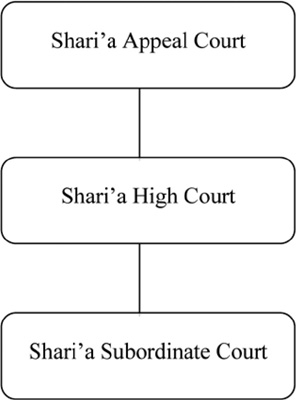

In contrast, the Malaysian civil court system has two levels. The superior level comprises the Federal Court4 and the Special Court division,5 the Court of Appeal,6 and two High Courts of coordinate jurisdiction,7 one in Malaya and one in Sabah and Sarawak. The second level is the subordinate court, consisting of the Sessions Court,8 the Magistrates Court,9 and the Court for Children (Figure 20.2).

According to the Malaysian laws, the proper forum to hear and decide on banking and finance matters, both conventional and Islamic, is the civil courts.10 Essentially, the first court to hear such matters is the High Court. For the Islamic commercial division of the High Court of Kuala Lumpur in Jalan Duta alone, more than 3,500 Islamic finance cases had been registered for determination by the court from 1983 through January 2010.11

Notably, the rule of law is an important concept in any dispute brought before a judge. Within the context of Shari’a, the rule of law is embodied in the source of Shari’a itself. Therefore, the judge must base decisions on the rule of law and not on the rule of authorities. In other words, the judge must follow the guidance prescribed by the Shari’a and must not deviate from it. Nevertheless, judges are bound to uphold the federal constitution of Malaysia as the supreme law of the land, as expressly provided by article 4 of the constitution: “This Constitution is the supreme law of the Federation ….” Thus, judges are under the obligation to uphold the rule of law, but this source of the law is the federal constitution and the written rules, as opposed to the Shari’a.

Fig. 20.2 Structure of the Malaysian civil courts

Apart from the obligation of judges to the rule of law, the Malaysian community is receptive to the idea of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms that range from negotiation and conciliation to mediation and arbitration. With respect to mediation, the Central Bank of Malaysia formed the Financial Mediation Bureau (FMB) to resolve complaints by and against financial institutions.

Negotiation is a consensual bargaining process in which the parties attempt to reach an agreement on a dispute or a potentially disputed matter. The essence of negotiating here is to achieve an advantage that is not possible by unilateral action. Meanwhile, in mediation a neutral person—the mediator—examines the claims of the parties and assists them in reaching a negotiated settlement for the dispute.

Mediation is used either before a dispute gets to court or any time the matter remains pending in court before judgment is delivered. In Malaysia, section 14 of the Legal Aid (Amendment) Act 2003 provides exclusively for mediation. The FMB, launched January 20, 2005, under the purview of the Central Bank of Malaysia, handles mediation for Malaysia’s banking and finance industry. The FMB covers disputes against commercial banks, Islamic banks, takaful operators, and development financial institutions, as well as selected payment system operators and nonbank issuers of credit and charge cards.

Arbitration is also an option that the parties may use to resolve their dispute. They must submit the dispute for consideration at the Regional Center for Arbitration in Kuala Lumpur or at other arbitration centers elsewhere in the world. This method settles commercial disputes through a binding decision. The Malaysia Arbitration Act 2005 relates to the conduct of arbitrations. It substantially follows the English Arbitration Act 1950, which covers (a) matters of arbitration; (b) arbitrators and umpires; (c) conduct of proceedings and witnesses; (d) provision for awards, costs, fees and interest, special cases, remission, and setting-aside awards; (e) enforcement of awards; and (f) additional provisions related to arbitration. The Kuala Lumpur Regional Centre for Arbitration (KLRCA) issued the 2007 KLRCA Rules for Islamic Banking and Financial Services Arbitration specifically for adoption into Islamic finance matters. Independent of the Malaysian government, the KLRCA administers arbitration under the auspices of the Asian-African Legal Consultative Organization, which comprises 48 member states. The KLRCA regulations of 1996 provide for the privileges and immunities of certain organizations, including the KLRCA.

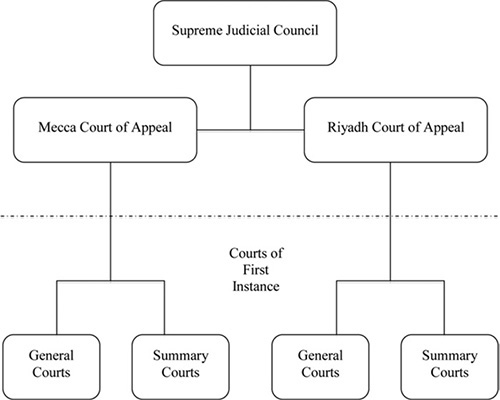

Fig. 20.3 Current structure of the Saudi Arabian courts

Saudi Arabia has three judicial bodies: (a) the Ministry of Justice, with courts of first instance, courts of appeal, and the high courts; (b) the independent judicial authorities known as the Boards of Grievances, or Diwan al-Mazalim; and (c) the semijudicial committees that work under the supervision of a ministry, such as the Committee for the Settlement of Banking Disputes of Saudi Authority Monetary Agency (SAMA) and the Committee for the Settlement of Customs Disputes, which belong to the Ministry of Finance (Baamir 2010).