Sections 113 and 110(1): Conditional Payment Clauses

SECTIONS 113 AND 110(1): CONDITIONAL PAYMENT CLAUSES

What Types of Conditional Payment Provisions Are Likely to Be Effective and which Ineffective? | |

(3) What Happens if a Conditional Payment Clause Is Rendered Ineffective? |

(1) Overview

Introduction and Summary

16.01 This chapter examines the prohibition on certain types of conditional payment clauses, including pay-when-paid clauses, under the Housing Grants Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 (‘the 1996 Act’) and the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009 (‘the 2009 Act’). It identifies the types of provisions that are prohibited, and considers the interaction of ss. 113 and 110(1) of the Acts, both of which are relevant to assessing whether or not a payment provision may be deemed ineffective:

1. Section 113(1) prohibits payments being made conditional upon payment being received from a third party except in cases where the third party is insolvent as defined by s. 113(2)–(5).

2. Arrangements that make payment conditional upon some other event, such as a certificate being issued under the subcontract in question or under a superior contract may still be valid, although they may cease to be so for contracts entered into under the provisions of the 2009 Act.

3. The decision in Midland Expressway indicates that, even under the 1996 Act, the courts will not look favourably on such arrangements where they have the effect of a pay-when-paid clause.

4. Pay-when-certified arrangements may also be invalid where they provide an inadequate mechanism for determining the amounts or timing of payments or allow the paying party to profit from its own breach.

5. Pay-when-paid (and probably pay when certified) arrangements will be construed strictly according to their terms and may be subject to the reasonableness test where the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 applies.

6. If the contract contains an ineffective pay-when-paid clause then some or all of the payment provisions of the the Scheme for Construction Contracts (‘the Scheme’) will apply.

(2) What Types of Provision Are Prohibited?

Pay-when-Paid Clauses under the 1996 Act

16.02 Section 113(1) of the 1996 Act renders ineffective any contract term which makes payment conditional on the payer ‘receiving payment from a third person’. This prohibition on pay-when-paid clauses applies in all situations except where the third person is insolvent, or where any other person is insolvent and payment by that other person is, under the contract (directly or indirectly), a condition of payment by that third person. Thus, in a chain of contracts the insolvency of a party up the line can mean that pay-when-paid provisions down the line are effective. The remainder of s. 113, in subclauses (2)–(5), describes what constitutes an insolvency situation for the purposes of the provision. Section 113(6) allows that, if a contract provision is rendered ineffective by sub-s. (1), the parties are free to agree other terms for payment. Failing that, the relevant terms of the Scheme apply to provide a mechanism for determining what payments are due and when (see Chapter 12).

16.03 Section 113 prohibits only those clauses which make payment conditional on the payer actually receiving payment from a third person. Clauses which made payment conditional on any other event, such as certificates being issued under contracts up the line, apparently remained valid under the 1996 Act, even though their effect might be the same in terms of delaying or frustrating payment. If a contractor was able to require that a subcontractor must wait until confirmation was received from the ultimate employer that the claim would be met, then s. 113(1) could be said to have very little protective effect.

Conditional Payment Clauses under the 1996 Act

16.04 There may have been a temptation following the enactment of the 1996 Act to view pay-when-paid clauses as a special type of clause singled out for statutory reprobation. Unsurprisingly, therefore, contract draftsmen appear to have been careful not to include clauses which made payment conditional on the receipt of payments in their contracts. However, as has been seen, pay-when-paid clauses are only one type of clause which may avoid or delay payment to a contractor or subcontractor.

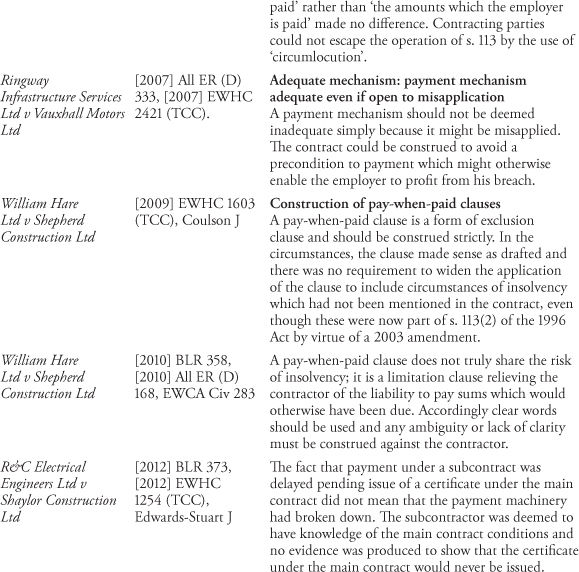

16.05 One approach which has been taken by subcontractors faced with other types of conditional payment clause has been to demand that it should be treated as a restriction or exclusion clause and therefore construed strictly against the requirements of the 1996 and 2009 Acts to ensure not only that it does not offend against s. 113, but that it also provides an ‘adequate mechanism’ for payment as required by s. 110(1). In the cases of Alstom Signalling Ltd v Jarvis Facilities Ltd (2004)1 and Ringway Infrastructure Service Limited v Vauxhall Motors Limited (2007),2 the courts were asked to consider whether conditional payment clauses amounted to payment mechanisms which were ‘inadequate’ contrary to the requirements of s. 110(1), because payment could be frustrated by inaction of the contractor. These cases are considered in detail at 12.34–12.36 and 13.21–13.23 and relate to clauses which, in effect, made the timing of payments conditional upon certificates having been issued. In the Alstom case, payment dates were determined by the timing of certificates issued under a superior contract. In Ringway, the timing depended upon a payment notice having been issued under the contract in question. In both cases, however, the judges were willing to construe the contracts so that the payment mechanism would be adequate provided that the contractor did not breach its obligations and fail to issue or pursue certificates indefinitely.

16.06 A more robust view was taken in Midland Expressway v Carillion Construction Ltd and ors (No. 2) (2005) (Key Case).3 The clause in question related to payment for varied work, and purported to limit the subcontractor’s recovery to the amounts which the contractor was entitled to be paid by the Secretary of State under a corresponding change to the concession agreement. Jackson J considered the arrangement to be, in effect, the type of pay-when-paid arrangement against which Parliament had legislated. The use of the words ‘entitled to be paid’ rather than ‘is paid’ could not save it from being considered so and contracting parties could not escape the operation of s. 113 by the use of ‘circumlocution’.4 The judge gave six reasons for finding that the offending clause was caught by s. 113, one of which was the fact that the practical consequence of the clause was that the contractor would not be paid for variations unless the concessionaire had received a corresponding sum under the concession agreement. The clause was therefore deemed ineffective.

16.07 The approach taken by Jackson J was to construe the words of the contract strictly to determine whether they offended not only the provision but also the intent of the s. 113. Clauses which had the effect of preventing the subcontractor from being paid until the contractor was paid would be contrary to the Act.

16.08 A strict approach was also taken both at first instance and in the Court of Appeal in William Hare Ltd v Shepherd Construction Ltd (2009).5 Here Coulson J identified that a pay-when-paid clause which operated in the event of the employer’s insolvency was, in effect, a form of exclusion clause. Consequently, it was required to be construed strictly in accordance with its terms, and words should not be implied to give effect to other intentions, even where there appeared to have been a mistake. The Court of Appeal agreed:6

17. … this clause was not truly ‘sharing’ the risk of insolvency, it was relieving Shepherd of a liability to pay which they otherwise had and it was for Shepherd to get a clause of this nature right if they wished to rely on it.

16.09 The implication of these latest decisions is that pay-when-paid clauses (and possibly other clauses which make payment conditional on matters outside of the subcontractor’s control), will be construed strictly and treated as exclusion clauses. This would appear to allow scope for subcontractors employed both before and after 1 October 2011 to argue that conditional payment clauses do not comply strictly with the words or intent of the relevant Act, and/or should be subject to the provisions of the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977.

Conditional Payment Clauses under UCTA

16.10 Where a subcontractor contracts on a contractor’s standard terms, then the provisions of the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 may apply to require that clauses which exclude or restrict a party’s rights are subjected to the test of reasonableness as set out in s. 3(2). As a result of the decision in Hare v Shepherd it would appear that pay-when-paid clauses, and possibly other types of conditional payment provisions, are now considered to be forms of exclusion clause which may be subject to UCTA.

Conditional Payment Clauses under the 2009 Act

16.11 The risk that the prohibition on pay-when-paid clauses could be rendered largely ineffective by the type of circumvention seen in Midland Expressway has been addressed under the 2009 Act. This introduces s. 110(1A) which prevents the amounts or timing of payments being made conditional on:

• the performance of obligations under another the contract or

• a decision by any person as to whether the obligations under another contract have been performed.

Section 110(1D) relates only to the timing, and not the amount, of payments, and renders ineffective any provision which requires the date on which the payment becomes due to be determined by the issue of a notice stating the amounts due under the contract.

16.12 In effect, s. 110(1A) and (1D) prohibits contractors from using the non-issuance of any certificate or notice under either the main contract with the employer, or under the subcontract itself, as a reason for avoiding or delaying payment to the subcontractor. Section 110(1A) also prevents matters being taken into account which affect only the performance of the contractor under the main contract as influencing the timing and amounts of payments due to the subcontractor. Such arrangements are now identified as examples which contravene the requirement of s. 110(1) of the original 1996 Act that every construction contract must contain an ‘adequate mechanism’ for assessing the amounts and timing of payments. This is not to say that a subcontractor could not argue that these types of arrangements provided an inadequate mechanism under contracts entered into prior to the 2009 Act. Such arguments have been made and, given the right circumstances, could be successful as discussed above.

16.13 Section 110(1B) and (1C) excludes from the ambit of s. 110(1A) pay-when-paid arrangements since these are already covered by s. 113, and certain types of management contracts because these are necessarily dependent upon obligations being performed under another contract, namely the works contract or subcontract which the contractor has been engaged to manage. Section 110(1D) continues to apply to management contracts so that the timing of the contractor’s payment cannot be dependent on the issue of a notice under the management contract in question.

16.14 The 2009 Act applies to construction contracts entered into after 1 October 2011. However, s. 110(1A) does not apply to subcontracts entered into under PFI arrangements in England and Wales by virtue of the exclusion orders which came into force on the same date.7 Thus, even though the amendments introduced by the 2009 Act answer directly the circumstances which gave rise to the decision in Midland Expressway, first-tier subcontracts under PFI arrangements (such as the one under discussion in that case) will not be caught by the new prohibition. That is not to say that Midland Expressway might have been decided differently under the 2009 Act as discussed immediately below.

Conditional Payment Clauses under PFI Contracts

16.15 The decision in Midland Expressway caused some alarm amongst those advising governments and PFI concessionaires. If variations were required to be assessed and paid without any equivalent funding relief from government and private funding partners, then the claims might not be met. Moreover this was a risk which PFI subcontractors understood and were generally in a better position than the concessionaire company to manage through their project-change controls.

16.16 Parliament appears to have accepted these arguments by excluding first-tier PFI subcontracts from s. 110(1A) as imported by the 2009 Act.8 This means that clauses which make payment conditional on the performance of obligations or certification under a superior contract will not automatically be deemed ineffective in first-tier PFI arrangements. It follows, however, that they may still be deemed ineffective in particular circumstances where a contractor can show that a clause offends either s. 113 or the wider provisions of s. 110(1), which are not limited by the examples given in s. 110(1A) and (1D). A clause which seeks to exclude or restrict a PFI subcontractor’s entitlement to payment must still be construed strictly, and may be deemed ineffective if it does not provide an adequate mechanism for payment or contravenes the intent of s. 113. The decision in Midland Expressway has not been overturned, and it remains possible that equivalent funding-relief clauses of the type encountered in that case will not be enforced in future for the reasons given in the case.

The Insolvency Exemption under s. 113

16.17 The insolvency exemption casts a long shadow over the anti-pay-when-paid provisions of both the 1996 and 2009 Acts. It allows parties to agree clauses which limit the contractor’s liability to pay subcontractors to amounts recovered from an insolvent third party.

16.18 The definition of insolvency contained in s. 113(2)–(5) is restricted and does not include voluntary arrangements with creditors or voluntary winding up (provided there is a declaration of solvency under s. 89 of the Insolvency Act 1986). However, pay-when-paid arrangements will remain effective in the case of a company entering into formal insolvency arrangements involving an administration or winding-up order, or the appointment of an administrative receiver.

16.19 Section 113(2)(a) has been amended by the Enterprise Act 2002 (Insolvency Order) 20039 to also include situations when a company enters administration within the meaning of Schedule B1 to the Insolvency Act 1986. Schedule B1 extends the circumstances in which companies can be placed into administration: as well as allowing for the court to make an administration order (as applied prior to 2002), an administrator can now be appointed by the holder of a floating charge, or by the company or its directors, merely by lodging the necessary forms. Whilst the stated intention of this is to streamline the process for administration, its effect is that an administrator can now be appointed through a process of self-certification without the need for a court hearing or for a court order to be made. The implications of this were considered in William Hare Ltd v Shepherd Construction Ltd (2009)10 (Key Case) which is considered below.

16.20 In the case of partnerships and individuals, s. 113(3) and (4) provides that pay-when-pay clauses remain effective where a partnership is made subject to a winding-up order, or a bankruptcy order is made against an individual, or, in both cases, where their estates are subject to a sequestration order in Scotland or where they grant a trust deed for their creditors. Section 113(5) makes similar provision for companies, partnerships, and individuals in Northern Ireland and in any country outside of the United Kingdom on the occurrence of any event corresponding to those specified in sub-ss. (2), (3), or (4).

16.21 It is worth noting that the insolvency exemption applies only to pay-when-paid clauses and not to the clauses which are now prohibited by s. 110(1A) and (1D) of the 2009 Act. This appears to recognize that certification functions should continue regardless of an employer’s insolvency, and it is only the risk of non-payment itself which may be passed on to subcontractors. If the contractor has already certified payment to a subcontractor when an employer becomes insolvent, then a clause permitting him to withhold payment may be effective without the need to serve a withholding or pay-less notice (Melville Dundas Ltd v George Wimpey UK Ltd [2007]11 as confirmed by s. 110(10) of the 2009 Act).