Sections 109 and 110(1): Interim and Final Payments

SECTIONS 109 AND 110(1): INTERIM AND FINAL PAYMENTS

(1) Overview

Introduction and Summary

12.01 This chapter looks at the circumstances in which s. 109 applies to create a right to interim payment in contracts over 45 days’ duration. It also considers the requirement under s. 110(1) to include an ‘adequate mechanism’ to determine the amounts and timings of payments. Both of these sections set minimum requirements which must be observed in the parties’ contract, otherwise the provisions of the Scheme for Construction Contracts (‘the Scheme’) will apply.

12.02 Neither ss. 109 nor 110(1) have been amended substantially under the Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009 (‘the 2009 Act’), and those amendments which have been made relate almost entirely to the prohibition on pay when certified clauses which is discussed at Chapter 16 below. The sole exception to this is a minor drafting amendment in s. 109(4) which has been made for the purposes of consistency with the new wording of ss. 110A, 110B, and 111(1).

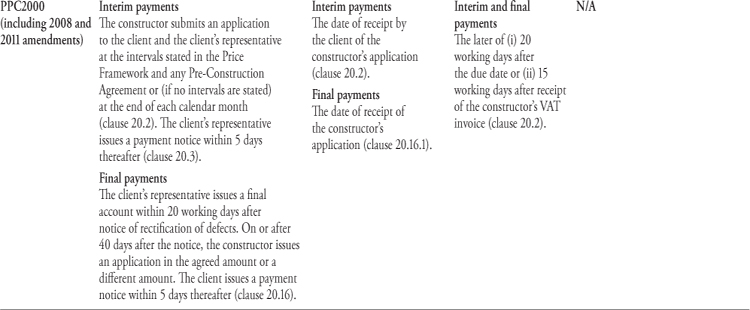

12.03 The requirements for providing an ‘adequate mechanism’ to determine the dates and amounts of payments are summarized below:

1. All construction contracts must contain an adequate mechanism for determining what payments become due and when. In the case of contracts over 45 days’ duration, this must include an adequate mechanism for determining interim payments as well as a final payment (s. 109).

2. If the parties have not provided for interim payments in contracts of over 45 days’ duration, the Scheme will apply a payment interval of 28 days.

3. The question of whether the parties have provided an ‘adequate mechanism’ is one of fact, not law. What will be adequate in some cases will be inadequate in others; however the requirement of certainty is a central ingredient.

4. If the parties have failed to provide an adequate (or any) mechanism to determine the amounts and dates of payments, the Scheme will apply to ‘fill the gaps’.

5. All construction contracts are required to stipulate a final date for payment. If they do not, then the Scheme applies so that the final date for payment is 17 days after the due date.

(2) The Right to Interim Payment under s. 109

Introduction

12.04 Section 109 creates a statutory right for a contractor or subcontractor to be paid before work is complete. Previously, such arrangements were left entirely for the parties to agree, often on uncertain terms. If work continued for prolonged periods, contractors and subcontractors undertook a high risk that they might expend significant sums in employing labour and providing materials with no right (or no enforceable right) to receive payment until many weeks or months afterwards. In such circumstances, cash flow would be severely restrained and if disputes arose, there was a risk that the contractor or subcontractor might face insolvency before they were resolved. Section 109 therefore underpins all of the other payment provisions of ss. 110–13 in creating an enforceable right to receive cash flow throughout a project, albeit that the parties remain free to decide the amounts and timings of such payments.1

12.05 Whilst it remains possible (subject to the risk that a payment mechanism may be found to be inadequate and therefore replaced by the Scheme) for a payer to avoid making regular or substantial payments by, for example, setting payment dates at a considerable distance from one another or specifying nominal amounts, the mere existence of the Act, and of s. 109 in particular, has strengthened the position of contractors and subcontractors so that such abuses should now be rare. The fact that the 2009 Act has recommended no change to the existing freedom of the parties to determine the conditions of interim payment, suggests that s. 109 has, by and large, worked as intended.

12.06 If a construction contract fails to allow for interim payments, then the relevant provisions of the Scheme apply to introduce payment intervals of 28 days and a method of valuation based on the actual costs of the work performed during the period.2 The relevant provisions of the Scheme are the same whether the parties have failed to make any allowance for interim payments (s. 109), or whether such provision has been made but it is not ‘adequate’ (s. 110(1)). The question of how the Scheme applies is considered in sections (4) and (5) below.

Duration of Work More than 45 Days

12.07 Section 109 provides that a party to a construction contract is entitled to payment by instalments, stage payments, or other periodic payments for any work under the contract unless:

1. it is specified in the contract that the duration of the work is to be less than 45 days or

2. it is agreed between the parties that the duration of the work is estimated to be less than 45 days.

12.08 The question of whether the work is of less than 45 days’ duration may not always be clear, and it is possible to think of numerous instances where works might extend beyond 45 days even if the parties had not originally intended that this should happen. For example:

1. where no start or finish dates are specified so that it is unclear whether the parties initially envisaged an original duration of less than 45 days

2. where the scope of work is extended, or delays occur, so that the original contract duration is extended beyond 45 days

3. where the contract is for call-off works so that the duration of the contract is longer than 45 days, but works may only be carried out on a few days throughout this period.

12.09 In such cases, it will be a matter of construction of the contract whether the parties have agreed that the duration of the work was estimated to be less than 45 days. The mere fact that works have extended beyond their original intended duration is unlikely to satisfy this requirement, even in cases where additional works have been instructed or extensions of time granted for matters beyond the payee’s control. In both cases, unless the additional work was foreseen at the start of the contract, it would not invalidate the parties’ original agreement as to the estimated duration. However, in cases where it is envisaged at the start of the works that they will be extended in due course, whether, for example, as a result of scope still being specified or as a result of provisional sum items within the bills of quantities, it would probably be prudent to include a regime for interim payments or risk the Scheme being implied.3 Equally, framework agreements and term contracts should probably include a provision for interim payment, if not in the main agreement, at least in the terms of any work order instructed of more than 45 days’ duration.

12.10 Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the likelihood that the works involved are of small value, there are no reports of the courts having been called upon to decide any cases where it has been argued that the interim payment provisions should not apply because the works were of less than 45 days’ duration. However, in Tim Butler Contractors Ltd v Merewood Homes Ltd (2002)4 this question was considered by an adjudicator who decided that the parties had neither specified nor agreed a duration less than 45 days.

12.11 The adjudicator’s decision was upheld by Judge Gilliland as being, right or wrong, a decision which was within the adjudicator’s jurisdiction to make. Whilst this case provides little guidance in so far as the parties’ agreement was evidenced by a chain of correspondence unlikely to be repeated elsewhere, it does at least demonstrate that the courts are likely to view the implication of the payment provisions of the Scheme as matters solely of contract interpretation within an adjudicator’s jurisdiction to decide. Thus, if an adjudicator wrongly decides that the Scheme applies because the contract is of duration more than 45 days, this does not open up his decision to a jurisdictional challenge (as it would if he wrongly decided that the contract was a construction contract within the meaning of ss. 104–7).5

(3) Section 110(1): Providing an ‘Adequate Mechanism’

Introduction

12.12 Whilst s. 109 provides that construction contracts should contain a mechanism for interim payments if they are over 45 days’ duration, s. 110(1) contains details as to how and when both these and final payments should be made. Section 110 is not limited to contracts of longer duration and the provisions therefore apply whether or not the specified or estimated duration of the work is more than 45 days. The only difference between contracts of long and short duration, therefore, is that the payment mechanism will only to apply to a single, final payment in short contracts, whereas it will apply to both interim and final payments in contracts of longer duration.

12.13 The purpose of s. 110, like s. 109, is to ensure that contracts are drafted to include the adequate payment mechanisms. Provided they do, the Act will not interfere to substitute other provisions. However, if the contract does not include the adequate mechanisms, the Scheme will apply.

12.14 Section 110(1) requires every construction contract to provide an adequate mechanism for determining what payments become due. Contracts must also contain an adequate mechanism for determining when the payments become due and stipulate a final date for payment. This use of terminology is at first sight confusing as, for many people, the fact that a payment is due means that it should be paid immediately and not at some point in the future before the final date for payment. This situation can be particularly confusing when the parties agree a payment mechanism whereby both the due date and the final date for payment are some time after the payment has been invoiced, assessed and certified. However, the purpose of the due date is to provide certainty as to when during the long assessment process the payee’s right to be paid a particular sum crystallizes. The purpose of the final date for payment, on the other hand, is to set a long-stop date by which this payment must be made.6 The due date and the final date for payment thereby form a ‘window’ within which payment must be made, and there is no need to wait until the final day to make payment (although payers often do).

What Constitutes an ‘Adequate Mechanism’?

12.15 The question of what is an ‘adequate mechanism’ is one of fact. What is adequate in some circumstances will not be adequate in others: Mair v Arshad (2007) (Key Case). The issue is therefore open to subjective interpretation and questions were raised during the Committee proceedings on the original Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Bill as to whether minimum requirements should be laid down so that the question of adequacy did not become one that was frequently contested in the courts. In the end, this suggestion was rejected on the familiar ground that any further attempts to describe the essential features of the payment mechanism would constitute too great an intrusion on the parties’ freedom of contract.

12.16 Nevertheless, it seems that parties rarely have any difficulty in practice in agreeing a mechanism which meets the test of adequacy, or else recognizing where contract terms fall short of this standard and agreeing to substitute the Scheme. Indeed, the issue is not one that has been frequently before the courts, possibly because both parties and the draftsmen of standard-form contracts have used the Scheme to guide them. As Sheriff O’Carroll put it in Mair v Arshad (2007):

The adequacy of the mechanism is a question of fact though, no doubt, some assistance may be gained in the final assessment by reference to the Scheme.7

12.17 Taking the elements of the Scheme, therefore, a contract should satisfy the test of adequacy if it contains:

1. a clear payment interval or condition for interim payment in contracts over 45 days’ duration8

2. a provision for either the making of a claim by the payee or certification by or on behalf of the payer, in either case specifying the amount of the payment which is considered due and the basis on which it has been calculated9

3. in relation to interim payments, a method of valuation to support the assessment of the amount due10 and

4. a provision that payment should become due within a definite period of the invoice or certification,11 provided that failure by the payer or certifier to issue a certificate should not be allowed to delay payment indefinitely.12

12.18 Of course, this is not the only type of payment mechanism which will satisfy the test, and parties should not rely entirely on differences between the Scheme’s provisions and those of the contract in order to demonstrate inadequacy in the latter. The only binding obligation is to comply with the terms of the Act, which is drafted in far less prescriptive terms than the Scheme. The lack of one or all of the above elements will not necessarily be fatal. In simple contracts an agreement to make an unspecified advance without any method of valuation to support it, may be reasonable.13 Agreed schedules of payments on specific dates or on completion of sections of the work are also common and, provided they create sufficient certainty, are likely to be valid.

12.19 In the cases considered below, the common complaint relates to a lack of certainty as to the valuation and timing of payments. Although there is no standard which can be applied across all contracts, a contract mechanism which makes payment conditional on events which are reasonably certain to happen may be deemed adequate, even when the event is beyond the control of the parties: Alstom Signalling Ltd v Jarvis Facilities Ltd (2004) (Key Case). On the other hand, where the payment mechanism depends upon the parties reaching agreement on the amount of payments, without any timetable for agreement to be reached nor any mechanism for resolving any failure to agree other than by reference to adjudication, then the payment mechanism may fail the test: Maxi Construction Management Ltd v Mortons Rolls Ltd (2001) (Key Case).

12.20 For contracts entered into after the 2009 Act came into force, new ss. 110(1A) and 110(1D) identify that any provision which makes payment conditional upon the performance of obligations or on a payment notice or certificate having been given under another contract, will be deemed inadequate. Had such provisions been present in the 1996 Act, then some of the cases set out below may have been decided differently. Sections 110(1A)—(1D) are considered in Chapter 16 below.

Final Date for Payment

12.21 In addition to providing an adequate mechanism for determining what payments become due and when, s. 110(1) also requires the parties to a construction contract to specify a final date for payment. A contract payment scheme that does not identify a final date for payment is not an adequate mechanism: Karl Construction (Scotland) Ltd v Sweeney Civil Engineering (Scotland) Ltd (2000) (Key Case). The final date for payment is the last date by which the payer must make payment of the amount due, unless it has served a notice of its intention to withhold or pay less. If the payer fails to do so, then the payee may suspend performance of the works in accordance with s. 112.14

12.22 The parties are free to decide the final date for payment, and it is common for the date to be later in respect of final payments than it is for interim payments to allow the payer time to check the final account. If the parties do not stipulate a final date for payment in relation to any amounts which may become due (whether interim, final, or any other payments) then the Scheme applies to provide that this shall be 17 days from the date that the payment becomes due. Equally if the parties specify a final date for payment which is conditional on other events occurring, then this must satisfy the test of adequacy in exactly the same way as required for the due date.15

12.23 The difference between the due date and final date for payment was considered by the House of Lords in the case of Reinwood Ltd v L. Brown & Sons Ltd (2008)16 in which it was stated that the obligation to pay arose and was crystallized on the due date, whilst the final date for payment was ‘akin’ to making time of the essence:

49. … A sum becomes due under a certificate when it is issued, and the ‘final date for payment’ is the date by which failure to pay can have serious consequences for the employer. As my noble and learned friend, Lord Walker of Gestingthorpe, observed during the argument, the function of the ‘final date’ is akin to making time of the essence of the payment as at that date.17

12.24 It is possible that a dispute may arise as to the amount to be paid even before it is required to be paid. In All in One Building & Refurbishments Ltd v Makers (UK) Ltd (2005)18 the contract had been brought to an end with each party blaming the other for the repudiation. Regardless of the employer’s position than no sums were yet due to be paid, Judge Wilcox upheld the adjudicator’s decision that a dispute had crystallized such that All in One was entitled to apply for determination of the amounts due to be paid to them for the alleged financial consequences of the breach:

27. [The employer’s] fallback argument that the assessed figures were akin to a draft final account, and that because under the contract two months was allowed for payment of a final account a dispute would not crystallise until the expiration of that period I also reject. The contractual date for payment is prescribed in the contract depending upon whether it is characterised as an interim payment or a final payment, but a distinction must be drawn between the date for payment and an entitlement to payment. It was the entitlement to payment that was being denied in relation to these claims. The contract may prescribe a time when payment becomes due and that may be a material factor amongst many others in arriving at the conclusion as to whether a claim is denied or not. It is not determinative as to whether a dispute has arisen.

The 2009 Act

12.25 The 2009 Act makes significant changes to the notification provisions contained in ss. 110(2) and 111. Although these are considered in detail in the next chapter, they include a right for the payee to issue a payment notice if the payer fails to issue a payment notice when required. Section 110B(3) now provides that where this happens, the final date for payment will be postponed by the same number of days after the date that the payer was to have given notice that the payee gives his notice. This provision has been reflected in some, but not all, of the standard forms considered at section 6 below.

Consequences of Missing the Final Date for Payment

12.26 Since s. 111(1) of both the 1996 and 2009 Acts imposes an obligation on the payer to pay the amount due (now the ‘notified sum’) by the final date for payment, it follows that any attempt to pay less than the amount that is properly due (which may be less than the amount of the payment application) without giving notice constitutes a breach of contract. Stipulations as to time for payment are not generally of the essence in commercial contracts unless a contrary intention appears from the terms of the contract.19 Their Lordships’ judgment in Reinwood v Brown indicates that the final date for payment has this effect and that there should be no separate need to serve notice making time of the essence.20 Even so, the failure is not automatically a repudiation of the contract, giving rise to a right to terminate. The breach must still go to the root of the contract.21 Whilst it is unlikely that a repudiatory breach would occur in the case of one or more short delays in making payment, it may occur when persistent late or non-payment causes a cumulative effect which may be so serious as to justify the innocent party bringing the contract to a premature end.22

12.27 The 1996 Act anticipates these problems and provides its own remedy for breach of contract in failing to pay by the final date for payment. This is contained in s. 112 and provides that a payee may suspend performance provided that certain conditions apply. The right to suspend appears to supplement and not to replace the payee’s other rights in such circumstances, including the right to terminate (in cases where this arises) and a right to interest on late payment either under the contract or under the Late Payment of Commercial Debts (Interest) Act 1998. It should be noted, however, that the question of whether a payee was justified in terminating the contract where a statutory right of suspension existed has not yet been tested by the courts.