Secret Trusts and Mutual Wills

Secret trusts and mutual wills

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

■ identify and distinguish between the two types of secret trust

■ understand the theoretical justification for enforcing secret trusts

■ comprehend the requirements for the creation of fully and half-secret trusts

■ follow the arguments regarding unresolved issues relating to secret trusts

■ appreciate the requirements for the creation of trusts of mutual wills

10.1 Introduction

A secret trust is an equitable obligation communicated to an intended trustee during the testator’s lifetime, but which is intended to attach to a gift arising under the testator’s will.

testator

A person who dies having made a valid will.

A testator who wishes to create a trust over his property upon his death is required to express this intention as well as the terms of the trust in his will. The formalities necessary to create a valid will are required to be complied with. These formalities are enacted in s 9 of the Wills Act 1837 (as amended). The basic requirement is the need for writing signed by the testator and witnessed by two or more witnesses. The secret trust is an exception to this rule because in limited circumstances where a testator has not fully complied with the necessary formalities, equity will nevertheless impose a duty upon the party acquiring the property under the will (legatee or devisee) to carry out the wishes of the testator. This will require the legatee or devisee to hold the property upon trust for the secret beneficiaries.

On a testator’s death his will becomes a public document and wills are consequently open to public scrutiny. But the testator may wish to make provision, after his death, for what he considers to be some embarrassing object, such as a mistress or an illegitimate child or any object that he does not wish to be disclosed to the public. To avoid adverse publicity, he may make an apparent gift by will to an intended trustee, subject to an understanding to hold the property for the benefit of the secret beneficiary. In construing the will the courts adopt an approach which is similar to construction of the terms of a contract, save when s 21 of the Administration of Justice Act 1982 is applicable in respect of meaningless or ambiguous terms (in this case extrinsic evidence may be admitted). In other words, despite the will being a unilateral document and contracts being bilateral agreements, the approach of the courts in the context of interpretation is the same. This was stated by Lord Neuberger MR in Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals v Sharp [2010] EWCA 1474.

JUDGMENT

| ‘The court’s approach to the interpretation of wills is, in practice, very similar to its approach to the interpretation of contracts. Of course, in the case of a contract, there are at least two parties involved in negotiating its terms, whereas a will is a unilateral document. However, it is clear … that the approach to interpretation of unilateral documents … is effectively the same as the court’s approach to the interpretation of a bilateral or multilateral document such as a contract.’ |

In interpreting a contract or a will the objective of the court is to ascertain the intention of the parties or the testator. It gives effect to the meaning of relevant words in the light of the natural and ordinary meaning of those words, the context of any other provisions of the document, the facts known to the parties or the testator at the time that the document was executed but ignoring subjective evidence of the parties’ or testator’s intention, see Marley v Rawlins [2014] UKSC 2, in the context of proceedings to rectify a will which, by an oversight, was signed by the wrong party.

10.2 Two types of secret trust

There are two types of secret trust:

■ fully secret trusts;

■ half-secret trusts.

A fully secret trust is an obligation which is fully concealed on the face of the will. The obligation is communicated to the legatee during the lifetime of the testator and the will transfers the property to the legatee without mention of the existence of a trust, i.e. both the existence and a fortiori terms of the trust are fully concealed on the face of the instrument creating the trust, namely the will, for example a disposition by will ‘to A absolutely’.

legatee

A person who inherits personal property under a valid will, as opposed to a ‘devisee’ who takes real property under a will.

a fortiori

More conclusively.

A half-secret trust is intended when the will indicates or acknowledges the existence of the trust but the terms are concealed on the face of the will. The trustee will then take the property on trust subject to a valid communication of the terms effected inter vivos, for example a disposition by will ‘to A on trust for purposes communicated to him’.

Thus, assuming there has been a valid communication of the terms of the trust, the category of secret trust involved depends on whether the trust has been acknowledged on the face of the will or not. This is important, for the two types of secret trust are subject to different rules.

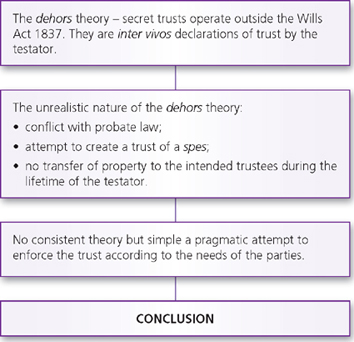

In enforcing secret trusts, equity does not contradict s 9 of the Wills Act 1837, as amended, because the trust operates outside (dehors) the Wills Act. Indeed, the secret trust complements the will in that a valid will is assumed, but it is recognised that the will on its own does not reflect the true intention of the testator. The bare minimum requirements are a validly executed will which transfers property to the trustees, whether named as such under the will or not; and the acceptance by the trustees inter vivos of an equitable obligation. Section 15 of the Wills Act 1837 is not applicable in this context. Section 15 of the 1837 Act enacts that an attesting witness (including his spouse) loses his interest under the will. It will be recalled that one of the formalities under the Wills Act 1837 involves two or more attesting witnesses. The Wills Act 1968 amended this requirement to allow additional attesting witnesses (and their spouses) exceeding two to acquire property under the testator’s will. Accordingly, if there are three attesting witnesses under a will and one of these has been bequeathed property under the will, that witness’s interest will not lapse. In Re Young [1951] Ch 344, the court decided that the secret trust operated outside the will in the sense that it was immaterial that one of the intended beneficiaries under the trust, as distinct from the will, witnessed the will.

attesting witness

Witness who signs a document verifying the signature of a person who executes the document.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Young [1951] Ch 344 A testator made a bequest to his wife subject to a direction made outside the will to the effect that on her death she would leave the property for the purpose which he had communicated to her. One of the purposes was that she would leave a legacy of £2,000 to the testator’s chauffeur, who witnessed the will. The question in issue was whether the chauffeur had forfeited his interest. The court held that the trust in favour of the chauffeur was not contained in the will but was created separately outside the will. Section 15 of the Wills Act 1837 was not applicable. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘The whole theory of the formation of a secret trust is that the Wills Act 1837 has nothing to do with the matter because the forms required by the Wills Act are entirely disregarded, since the persons do not take by virtue of the gift in the will, but by virtue of the secret trusts imposed upon the beneficiary who does in fact take under the will.’ |

| Danckwerts J |

A variation of the dehors theory is to the effect that the trust is created inter vivos and outside or independently of the will. The notion here is that the trust is created by reason of the personal obligation accepted by the legatee. Thus, the argument proceeds on the assumption that the date of the creation of the trust is during the lifetime of the settlor: see Re Gardner (No 2) [1923] 2 Ch 230. This theory is fundamentally flawed in both trusts and probate law. On the date of the communication of the terms of the trust to the legatee (trustee) the trustee has not acquired the intended property. Thus, there cannot be a valid trust. In probate law a will speaks from the date of the death of the testator. Before this date the legatee has merely a hope of acquiring a benefit under the will.

Traditionally, the trust property is transferred by will on condition that the trustee (who takes under the will as legatee or devisee) holds the property subject to an agreement entered into between the testator and himself. Likewise, the secret trust principles will extend to intestacies. These are occasions (as illustrated by Sellack v Harris (1708)) where the settlor decides not to make a will on the faith of a promise by his next of kin to dispose of the property in accordance with the settlor’s wishes as disclosed to him during the lifetime of the settlor.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Sellack v Harris [1708] 5 Vin Ab 521 A father was induced by his heir presumptive (entitled to realty on an intestacy before 1925) not to make a will on the ground that the heir himself would make provision for his mother After the death of his father, the heir refused to make provision as promised. The court held that the heir was obliged to make the relevant provision, for he had induced his father to refrain from making a will. |

10.3 Basis for enforcing secret trusts

The theoretical justification for enforcing secret trusts is said to be the need to prevent fraud. The court originally applied the maxim ‘Equity will not allow a statute to be used as an engine for fraud.’ The statute in this respect is the Wills Act 1837. The jurisdiction adopted by the courts in order to enforce secret trusts was to prevent the legatee or devisee fraudulently denying the binding nature of his promise and attempting to set up s 9 of the Wills Act 1837 as a defence, for example if, during his lifetime, a testator (T) made an agreement with A (a legatee) to the effect that on T’s death, 50,000 would be transferred to him to hold on trust for B and T made a will to that effect. Following T’s death, it would be a fraud on the estate of T and B for A to deny the agreement, or non-compliance with s 9 of the 1837 Act, and claim the property beneficially. The persons who may be the victims of the fraud by the legatee are the testator and the beneficiaries under the intended secret trust. Consequently the court will step in and compel A to honour his agreement. This theory was enunciated by Lord Westbury in McCormick v Grogan (1869) LR 4 HL 82:

JUDGMENT

| ‘My Lords, the jurisdiction which is invoked here by the appellant is founded altogether on personal fraud. It is a jurisdiction by which a Court of Equity, proceeding on the ground of fraud, converts the party who has committed it into a trustee for the party who is injured by that fraud … It is incumbent on the Court to see that a fraud … is proved by the clearest and most indisputable evidence. … The Court of Equity has, from a very early period, decided that even an Act of Parliament shall not be used as an instrument of fraud; and if in the machinery of perpetrating a fraud an Act of Parliament intervenes, the Court of Equity, it is true, does not set aside the Act of Parliament but fastens on the individual who gets a title under the Act, and imposes on him a personal obligation, because he applies the Act as an instrument for accomplishing a fraud.’ |

A similar view was stated by Lord Hardwicke in the earlier case of Drakeford v Wilkes (1747) 3 Atk 539:

JUDGMENT

| ‘[I]f a testatrix has a conversation with a legatee, and the legatee promises that, in consideration of the disposition in favour of her, she will do an act in favour of a third person, and the testator lets the will stand, it is very proper that the person who undertook to do the act should perform, because, as I must take it, if (the secret trustee) has not so promised, the testatrix would have altered her will.’ |

The justification for enforcing secret trusts put forward by Lord Hardwicke (above) appears to support both fully and half-secret trusts. Enforcement of the trust does not depend upon the actual fraudulent enrichment of the secret trustee. Support for this view may be found in the following authorities: Reech v Kennigate (1748) Amb 67, Stickland v Turner (1804) 9 Ves Jun 517, Chamberlain v Agar (1813) 2 V & B 257, Wallgrave v Tebbs (1855) 2 K & J 313, Re Fleetwood (1880) 15 Ch D 594, Barrow v Greenough (1796) 3 Ves Jun 152, Jones v Badley (1868) LR 3 Ch App 362, Re Cooper [1939] Ch 811, Re Boyes (1884) 26 Ch D 531, Russell v Jackson (1852) 10 Hare 204, Podmore v Gunning (1836) 8 Sim 644.

Lord Buckmaster, in Blackwell v Blackwell [1929] AC 318, identified the victim as the beneficiary under the intended secret trust. He said:

QUOTATION

| ‘A testator having been induced to make a gift on trust in his will in favour of certain named persons, the trustee is not at liberty to suppress the evidence of the trust and thus destroy the whole object of its creation, in fraud of the beneficiaries.’ |

However, in McCormick v Grogan, Lord Hatherley put forward a different interpretation of the notion of fraud. His view of the fraud focused on an inducement by the intended legatee (trustee) to assure the testator that the transfer of property to the legatee will be held upon trust in accordance with his wishes, and the legatee subsequently attempts to deny the promise. In the above example the court proceeded on the basis of frustrating A’s course of action if he induced T to transfer property to him in order to carry out T’s wishes, and after T’s death A attempts to claim the property beneficially by relying on the statute. half-secret trusts cannot be justified on this basis, for the will transfers the property to persons named as trustees and such persons are not allowed to take property beneficially. Thus, the trustee may not profit from his fraud. If the intended half-secret trust fails, a resulting trust will be set up.

JUDGMENT

| ‘This doctrine [secret trusts] evidently requires to be carefully restricted within proper limits. It is in itself a doctrine which involves a wide departure from the policy which induced the Legislature to pass the Statute of Frauds, and it is only in clear cases of fraud that this doctrine has been applied – cases in which the Court has been persuaded that there has been a fraudulent inducement held out on the part of the apparent beneficiary in order to lead the testator to confide to him the duty which he so undertook to perform.’ |

| Lord Hatherley in McCormick v Grogan (1869) |

But half-secret trusts cannot be justified on this basis, for the will transfers the property to persons named as trustees and such persons are not allowed to take property beneficially. The trustee may not profit from his fraud. If the intended half-secret trust fails, a resulting trust will be set up. The effect is that this notion of the fraud theory cannot justify the existence of half-secret trusts.

An alternative basis for enforcing secret trusts is the transfer and declaration theory. The approach here is that the will transfers the property to the trustee, subject to an express, conditional declaration of trust executed by the testator outside the will. The conditional declaration of trust will be activated when the trustee acquires the relevant property under the testator’s will. The secret trust becomes effective when the trustee acquires the property under the testator’s will, subject to the valid declaration. The court steps in and compels the trustee to carry out the wishes of the testator as indicated in the declaration. The conditional inter vivos declaration becomes effective on the death of the testator and specifically when the legatee acquires the property. The trust is not created inter vivos, but on death, and subject to an inter vivos declaration or communication of the testator’s wishes. This approach was advocated by Lord Sumner in Blackwell v Blackwell [1929] AC 318:

JUDGMENT

| ‘The court of equity finds a man in the position of an absolute legal owner of a sum of money, which has been bequeathed to him under a valid will and it declares that, on proof of certain facts relating to the motives of the testator, it will not allow the legal owner to exercise his legal right to do what he wishes with the property. In other words it lets him take what the will gives him and then makes him apply it as the Court of Conscience directs, and it does so in order to give effect to the wishes of the testator, which would not otherwise be effectual.’ |

A variation on this theory is the dehors analysis, as outlined above.

10.4 Requirements for the creation of fully secret trusts

■ The claimant is required to prove that the testator, during his lifetime, communicated the terms of the trust to the legatee. It is immaterial whether the communication was made before or after the execution of the will provided that it was made before the death of the testator. Communication may take place directly by means of an oral statement or in writing outside the will. In addition, communication may take place constructively, i.e. by delivery of a sealed envelope containing the terms of the trust to the trustee during the lifetime of the testator, but headed ‘Not to be opened before my death’. Provided that the trustee is aware that the contents of the envelope are connected with the testator’s will, communication is deemed to be effective on the date of the delivery of the envelope. This is illustrated by Re Keen [1937] Ch 236 (below).

■ The trustee is required to accept the trust obligation during the testator’s lifetime. This may be manifested by means of an acknowledgement by the legatee (trustee) to be bound by the terms of the trust. Alternatively, acceptance may exist through acquiescence or silence on the part of the legatee. Once the legatee is aware of the intention of the testator and this intention is complete in the sense that all the terms have been communicated to the legatee, he is bound to hold on trust for those purposes. The legatee is not required to do anything positive to demonstrate acceptance, he is deemed to accept the terms of the trust once he is aware of the testator’s wishes during his lifetime.

execution of a will

The signature of a testator in the presence of two or more attesting witnesses.

Brightman J, in Ottaway v Norman [1972] Ch 698, identified the basic requirements for a fully secret trust thus:

JUDGMENT

| ‘It will be convenient to call the person upon whom such a trust is imposed the primary donee and the beneficiary under the trust the secondary donee. The essential elements which must be proved to exist are: |

(i) the intention of the testator to subject the primary donee to an obligation in favour of the secondary donee; (ii) communication of that intention to the primary donee; and (iii) the acceptance of that obligation by the primary donee either expressly or by acquiescence. It is immaterial whether these elements precede or succeed the will of the donor.’ |

10.4.1 No agreement for transferee to hold as trustee

If there is no agreement between the testator and the legatee whereby the transferee is intended to hold as trustee, the transferee takes beneficially and may set up s 9 of the Wills Act 1837 as a defence. The distinction here is between a legacy simpliciter and a legacy upon trust.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Wallgrave v Tebbs [1855] 2 K & J 313 A testator, by will, transferred personal and real property to two individuals absolutely. The testator was contemplating the identities of the ultimate beneficiaries under the trust but failed, during his lifetime, to notify the two individuals of his selection. The court decided that the two individuals were entitled to the properties beneficially. They had not acted unconscionably by claiming the properties beneficially because they did not make an agreement to hold on trust. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘I am satisfied that I ought not overstep the clear line which separates mere trusts from devises and bequests … Where a person, knowing that a testator in making a disposition in his favour intends it to be applied for purposes other than for his own benefit either expressly promises, or by silence implies, that he will carry out the testator’s intention into effect, and the property is left to him upon the faith of an undertaking, it is in effect a case of trust and the court will not allow the devisee to set up the Statute of Frauds – or rather the Statute of Wills as a defence. But the question here is totally different. Here there has been no promise or undertaking on the part of the legatee. The latter knew nothing of the testator’s intention until after his death. Upon the face of the will, the parties take indisputably for their own benefit.’ |

| Wood VC |

10.4.2 Terms of trust not communicated

If the transferee agreed to hold the property on trust, but the terms of the trust have not been communicated during the testator’s lifetime, the transferee will hold the property on resulting trust for the testator’s heirs. The intended secret trust fails because there has been a failure to communicate the terms of the trust to the legatee during the lifetime of the testator. But, since the legatee is aware that he is required to hold on trust and acquires the property on the basis of this understanding, he holds the same on resulting trust for the testator. This principle was applied in Re Boyes (1884) 26 Ch D 531.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Boyes; Boyes v Carritt [1884] 26 Ch D 531 A testator, by will, transferred property to a legatee, having secured an agreement from the legatee to hold on trust. The testator died before he communicated the terms to the legatee The court decided that the intended secret trust failed but a resulting trust was created for the testator’s heirs. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘If the trust was not declared when the will was made, it is essential, in order to make it binding, that it should be communicated to the devisee or legatee in the testator’s lifetime and that he should accept that particular trust.’ |

| Kay J |

The fully secret trust obligation normally takes the form of the legatee (trustee) holding the property on trust for the secret beneficiary. Alternatively, the obligation may involve the legatee executing a will in favour of the secret beneficiary. In this event, the legatee may enjoy the property beneficially during his lifetime, but the obligation undertaken requires him to transfer the relevant property by his will to the named beneficiary. Accordingly, there are two beneficiaries involved in the transaction – the ‘primary beneficiary’ who acquires an interest for life and the ‘secondary beneficiary’ who is entitled to acquire the property under the will of the primary beneficiary.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Ottaway v Norman [1972] Ch 698 A testator, Harry Ottaway, by his will devised his bungalow (with fixtures, fittings and furniture) to his housekeeper, Miss Hodges, in fee simple and gave her a legacy of £1,500. It was alleged that Miss Hodges had verbally agreed with the testator to leave by her will the bungalow and fittings etc., and whatever ‘money’ was left over at the time of her death to the claimants, Mr and Mrs William Ottaway (the testator’s son and daughter-in-law). By her will, Miss Hodges left all her property to someone else. The claimants sued Mr Norman (Miss Hodges’ executor) for a declaration that the relevant parts of Miss Hodges’ estate were held upon trust for the claimants. The court decided that there was clear evidence that a fully secret trust was created only in respect of the bungalow and fittings etc., but not in respect of the ‘money’ The intended trust of the money was uncertain and void. Mr Norman as her executor therefore held the bungalow on trust for Mr and Mrs William Ottaway. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘I am content to assume for present purposes but without so deciding that if property is given to the primary donee on the understanding that the primary donee will dispose by his will of such assets, if any, as he may have at his command at his death in favour of the secondary donee, a valid trust is created in favour of the secondary donee which is in suspense during the lifetime of the primary donee, but attaches to the estate of the primary donee at the moment of the latter’s death. There would seem to be at least some support for this proposition in an Australian case Birmingham v Renfrew (1937) 57 CLR 666.’ |

| Brightman J |

10.4.3 Two or more legatees

Where a testator leaves property to two or more legatees but informs one or some of them (but not all of them) of the terms of the trust, the issue arises as to whether the uninformed legatees are bound by the communication to the informed legatees. The solution here depends on the timing of the communication and the status of the legatees. If (a) the communication was made to the legatees before or at the time of the execution of the will and (b) they take as joint tenants, the uninformed legatees are bound to hold for the purposes communicated to the informed legatees. The reason commonly ascribed to this principle is that no one is allowed to take property beneficially under a fraud committed by another. But if any of the above conditions is not satisfied, the uninformed legatees are entitled to take the property beneficially; the reason stated for this aspect of the rule is that the gift is not tainted with any fraud in procuring the execution of the will. Thus, if some of the legatees were told of the terms of the trust after the execution of the will but during the lifetime of the testator, the uninformed legatees will take part of the property beneficially. The informed legatees, of course, will hold on trust. In Re Stead [1900] 1 Ch 237, Farwell J reviewed the authorities and the justification for the rule, and confessed that he was unable to see any difference between a gift made on the faith of an antecedent promise and a gift left unrevoked on the faith of a subsequent promise to carry out the testator’s wishes. He added, however, that he was bound by the principle.

This rule, by its nature, may not be extended to half-secret trusts for the trustee on the face of the will is not entitled to the property beneficially.

10.5 Requirements for the creation of half-secret trusts

This classification arises where the legatee or devisee takes as trustee on the face of the will but the terms of the trust are not specified in the will: for instance T, a testator, transfers property to L, a legatee, to ‘hold upon trust for purposes that have been communicated to him’. The will acknowledges the existence of the trust but the terms have been concealed.

The following points are relevant in order to establish a half-secret trust.

The will is irrevocable and sacrosanct on the death of the testator

Accordingly, evidence is not admissible to contradict the terms of the will. To adduce such evidence would have the potential to perpetrate a fraud: for instance, if the will points to a past communication (i.e. a communication of the terms of the trust before the will was made), evidence is not admissible to prove a future communication. Similarly, since the will names the legatee as trustee, evidence is not admissible to prove that he is a beneficiary, even of part of the property. This is the position even though the testator may wish the legatee to receive part of the property beneficially. If the testator wishes to benefit the legatee (trustee) he is required to express his intention in a separate disposition under the will.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Rees [1950] Ch 204 A testator, by his will, appointed his friend H and his solicitor W to be executors and trustees and he devised and bequeathed all his property to ‘my trustees absolutely, they well knowing my wishes concerning the same’. The testator told the executors and trustees at the time of making the will that he wished them to make certain payments out of the estate and retain the remainder for their own use. After the payments were made, there was a substantia surplus remaining. The executors claimed that they were entitled to keep the surplus in that there was no secret trust but a conditional gift in their favour. The court held that the surplus could not be taken by the executors and trustees beneficially. The relevant clause in the will created a half-secret trust and the trustees were not entitled to adduce evidence to show that they were entitled beneficially. The surplus funds passed on intestacy to the next of kin. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘I agree with the judge that to admit evidence to the effect that the testator informed of the executors – or I will assume both of the executors – that he intended them to take beneficial interests, would be to conflict with the terms of the will as I have construed them; for the inevitable result of admitting that evidence and giving effect to it would be that the will would be regarded not as conferring a trust estate only upon the two trustees, but as giving them a conditional gift which on construction is the thing which, if I am right, it does not do.’ |

| Evershed MR |

Communication before or at the time of execution of the will

It is imperative that the testator communicate the terms of the trust before or at the time of the execution of the will and the intended trustees are required to accept (expressly or by acquiescence) the obligation to hold on trust before or at the time of the execution of the will. Thus, an agreement between the parties is required to be made at the time of the execution of the will. On this basis the terms of the trust may be proved and the equitable obligation will be effective.

CASE EXAMPLE

| Blackwell v Blackwell [1929] AC 318 A testator, by a codicil (an alteration of a will executed in accordance with the Wills Act 1837), bequeathed a legacy of £12,000 to five persons ‘to apply for the purposes indicated by me to them’. Before the execution of the codicil, the terms of the trust were communicated to the legatees and the trust was accepted by them all. The beneficiaries were the testator’s mistress and her illegitimate son. The claimant asked the court for a declaration that no valid trust in favour of the objects had been created, on the ground that parol evidence (oral evidence) was inadmissible to establish the trust. The court held that the trust was valid. Parol evidence was admissible to establish the terms of a half-secret trust in order to prevent the testator’s intention being fraudulently avoided. The evidence did not vary the will; it merely gave effect to the intention of the testator. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘Why should equity forbid an honest trustee to give effect to his promise, made to a deceased testator, and compel him to pay another legatee, about whom it is quite certain that the testator did not mean to make him the object of his bounty? … the testator’s wishes are incompletely expressed in his will.’ |

| Lord Sumner |

Communication after the execution of the will

If the agreement between the testator and the trustees is made after the execution of the will, even if this is made in accordance with the will and during the lifetime of the testator, it is settled law that such evidence may not be adduced to prove the terms of the trust. The reason given for this controversial principle was stated by Viscount Sumner in Blackwell v Blackwell [1929] AC 318:

JUDGMENT

| ‘A testator cannot reserve to himself a power of making future unwitnessed dispositions by merely naming a trustee and leaving the purposes of the trust to be supplied afterwards, nor can a legatee give testamentary validity to an unexecuted codicil by accepting an indefinite trust, never communicated to him in the testator’s lifetime … To hold otherwise would indeed be to enable the testator to give the go-by to the requirements of the Wills Act, because he did not choose to comply with them. It is communication of the purpose to the legatee coupled with acquiescence or promise on his part, that removes the matter from the provision of the Wills Act and brings it within the law of trusts.’ |

CASE EXAMPLE

| Re Keen [1937] Ch 236 A testator bequeathed a legacy to two legatees, A and B, ‘to be held upon trust and disposed of by them among such persons or charities as may be notified by me to them or either of them during my lifetime’. Prior to the execution of the will, A had been given a sealed envelope subject to the direction, ‘Not to be opened before my death’. A considered himself bound to hold the legacy subject to the terms declared in the envelope. The envelope contained the name of the beneficiary under the intended trust. Subsequently, the testator revoked the original will and executed a new will which contained an identical bequest. No fresh directions were issued to A, who was still prepared to carry out the testator’s wishes. After the testator’s death, an application was made to the court to determine whether the executors were required to distribute the property to A and B as trustees for the specified beneficiary or, alternatively, for the residuary estate. The Court of Appeal held that the trust failed and the property fell into residue on the grounds that: (a) The delivery of the envelope constituted communication of the terms of the trust at the time of delivery. Since this was made prior to the execution of the will and was inconsistent with the terms of the will (which referred to a future communication), the letter was not admissible. (b) The provision in the will contained a power to declare trusts in the future. This power was not enforceable and the terms of the intended trust were not admissible. |

JUDGMENT

| ‘In the present case, while clause 5 refers solely to a future definition, or to future definitions, of the trust, subsequent to the date of the will, the sealed letter relied on as notifying the trust was communicated before the date of the will. That it was communicated to one trustee only, and not to both, would not, I think, be an objection. But the objection remains that the notification sought to be put in evidence was anterior to the will, and hence not within the language of clause 5, and inadmissible simply on that ground, as being inconsistent with what the will prescribes.’ |

| Lord Wright MR |

But the theory underlying a secret trust (even a half-secret trust) is that it operates outside the will. The will merely transfers the property to the trustees who then hold subject to the obligation undertaken during the lifetime of the testator. The agreement between the testator and the trustees does not contradict the will but merely complements it, in that the will acknowledges a trust and the agreement supplies evidence of the trust. It is highly probable that the prohibition of post-will communications amounts to a confused or corrupt version of the probate doctrine of ‘incorporation by reference’. In accordance with this doctrine an unattested document (e.g. a letter) may be joined and read with an attested document (e.g. a will). The conditions are that the former document is executed before, or at the time of, and is specifically referred to in, the attested document. In these circumstances, in probate law, the unattested document becomes public in much the same way as the will. In half-secret trusts there is no general requirement that the communication of the terms of the trust to the trustees be made in writing as is required under the probate doctrine.

tutor tip

‘Secret trusts and the mutual wills doctrine, although not of regular occurrence in modern society, have a great deal of significance in equity.’