ROBBERY, BURGLARY AND OTHER OFFENCES IN THE THEFT ACTS

Robbery, burglary and other offences in the Theft Acts

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of robbery

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of robbery

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of burglary and related offences

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of burglary and related offences

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of taking a conveyance

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of taking a conveyance

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of blackmail

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of blackmail

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of handling stolen goods

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of handling stolen goods

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of making off without payment

Understand the actus reus and mens rea of making off without payment

Analyse critically all the above offences

Analyse critically all the above offences

Apply the law to factual situations to determine whether robbery, burglary or other offences under the Theft Acts have been committed

Apply the law to factual situations to determine whether robbery, burglary or other offences under the Theft Acts have been committed

student mentor tip

In the last chapter we focused on the offence of theft. This chapter discusses other offences contained in the Theft Act 1968, together with one offence from the Theft Act 1978. Some of these have theft as an essential element, such as robbery. Others are connected to theft, such as going equipped for theft or handling stolen goods.

14.1 Robbery

Robbery is an offence under s 8 of the Theft Act 1968 and is, in effect, theft aggravated by the use or threat of force.

SECTION

‘8 A person is guilty of robbery if he steals, and immediately before or at the time of doing so, and in order to do so, he uses force on any person or puts or seeks to put any person in fear of being then and there subjected to force.’

14.1.1 The actus reus of robbery

The elements which must be proved for the actus reus of robbery are:

theft

theft

force or putting or seeking to put any person in fear of force

force or putting or seeking to put any person in fear of force

In addition there are two conditions on the force, and these are that it

must be immediately before or at the time of the theft; and

must be immediately before or at the time of the theft; and

must be in order to steal

must be in order to steal

14.1.2 Theft as an element of robbery

There must be a completed theft for a robbery to have been committed. This means that all the elements of theft have to be present. If any one of them is missing then, just as there would be no theft, there is no robbery. So there is no theft in the situation where D takes a car, drives it a mile and abandons it because D has no intention permanently to deprive. Equally there is no robbery where D uses force to take that car. There is no offence of theft, so using force cannot make it into robbery.

Another example is where D has a belief that he has a right in law to take the property. This would mean he was not dishonest and one of the elements of theft would be missing, as seen in Robinson (1977) Crim LR 173.

CASE EXAMPLE

Robinson (1977) Crim LR 173

D ran a clothing club and was owed £7 by I’s wife. D approached the man and threatened him. During a struggle the man dropped a £5 note and D took it claiming he was still owed £2. The judge directed the jury that D had honestly to believe he was entitled to get the money in that way. This was not the test. The jury should have been directed to consider whether he had a belief that he had a right in law to the money which would have made his actions not dishonest under s 2(1)(a) of the Theft Act. The Court of Appeal quashed the conviction for robbery.

Where force is used to steal, then the moment the theft is complete, there is a robbery. This is shown by Corcoran v Anderton (1980) Crim LR 385.

CASE EXAMPLE

Corcoran v Anderton (1980) Crim LR 385

One defendant hit a woman in the back and tugged at her bag. She let go of it and it fell to the ground. The defendants ran off without it (because the woman was screaming and attracting attention). It was held that the theft was complete so the defendants were guilty of robbery.

However, if the theft is not completed, for instance if the woman in the case of Corcoran v Anderton had not let go of the bag, then there is an attempted theft and D could be charged with attempted robbery.

14.1.3 Force or threat of force

Whether D’s actions amount to force is something to be left to the jury. The amount of force can be small. In Dawson and James (1976) 64 Cr App R 170, one of the defendants pushed the victim, causing him to lose his balance, which enabled the other defendant to take his wallet. The Court of Appeal held that ‘force’ was an ordinary word and it was for the jury to decide if there had been force.

It was originally thought that the force had to be directed at the person and that force used on an item of property would not be sufficient for robbery. In fact this was the intention of the Criminal Law Revision Committee when it put forward its draft Bill. It said in its report that it would

QUOTATION

‘… not regard mere snatching of property, such as a handbag, from an unresisting owner as using force for the purpose of the definition [of robbery], though it might be so if the owner resisted’.

This point was considered in Clouden (1987) Crim LR 56.

CASE EXAMPLE

Clouden (1987) Crim LR 56

The Court of Appeal held that D was guilty of robbery when he had wrenched a shopping basket from the victim’s hand. The Court of Appeal held that the trial judge was right to leave to the jury the question of whether D had used force on a person.

It can be argued that using force on the bag was effectively using force on the victim, as the bag was wrenched from her hand. However, if a thief pulls a shoulder bag so that it slides off the victim’s shoulder, would this be considered force? Probably not. And it would certainly not be force if a thief snatched a bag which was resting (not being held) on the lap of someone sitting on a park bench.

This view is supported by P v DPP (2012) in which D snatched a cigarette from V’s hand without touching V in any way. It was held that as there had been no direct contact between D and V it could not be said that force had been used ‘on a person’. Therefore D was not guilty of robbery. The situation was analogous to pickpocketing where D is unaware of any contact. However, where the pickpocket (or accomplice) jostles V to distract him while the theft is taking place, there is force which could support a charge of robbery.

Fear of force

The definition of ‘robbery’ makes clear that robbery is committed if D puts or seeks to put a person in fear of force. It is not necessary that the force be applied. Putting V ‘in fear of being there and then subjected to force’ is sufficient for robbery. This covers threatening words, such as ‘I have a knife and I’ll use it unless you give me your wallet’, and threatening gestures, such as holding a knife in front of V.

CASE EXAMPLE

Bentham (2005), UKHL 18

D put his fingers into his jacket pocket to give the appearance that he had a gun in there. He then demanded money and jewellery. He was charged with robbery and pleaded guilty. He was also charged with having in his possession an imitation firearm during the course of the robbery contrary to s 17(2) of the Firearms Act 1968. His conviction for this was quashed by the House of Lords.

It was clear that D was guilty of robbery as he had sought to put V in fear of being then and there subjected to force. The fact that it was only his fingers did not matter for the offence of robbery. However, for the offence of possessing an imitation firearm there had to be some item and not just a part of D’s body. This was because what had to be possessed had to be a ‘thing’ and that meant something which was separate and distinct from oneself. Fingers were therefore not a ‘thing’. In addition, the House of Lords pointed out that if fingers were regarded as property for the purposes of s 143 of the Powers of Criminal Courts (Sentencing) Act 2000 then this created the nonsense that a court could theoretically make an order depriving D of his rights in them!

Robbery is also committed even if the victim is not actually frightened by D’s actions or words. If D seeks to put V in fear of being then and there subjected to force, this element of robbery is present. So if V is a plain clothes policeman put there to trap D and is not frightened, the fact that D sought to put V in fear is enough. This was shown by B and R v DPP (2007) EWHC 739 (Admin).

CASE EXAMPLE

B and R v DPP (2007)

V, a schoolboy aged 16, was stopped by five other school boys. They asked for his mobile phone and money. As this was happening, another five or six boys joined the first five and surrounded the victim. No serious violence was used against the victim, but he was pushed and his arms were held while he was searched. The defendants took his mobile phone, £5 from his wallet, his watch and a travel card. The victim said that he did not feel particularly threatened or scared but that he was bit shocked.

The defendants appealed against their convictions for robbery on the basis that no force had been used and the victim had not felt threatened. The Divisional Court upheld the convictions for robbery on the grounds that:

There was no need to show that the victim felt threatened; s 8 of the Theft Act 1968 states that robbery can be committed if the defendant ‘seeks to put any person in fear of being then and there subjected to force’.

There was no need to show that the victim felt threatened; s 8 of the Theft Act 1968 states that robbery can be committed if the defendant ‘seeks to put any person in fear of being then and there subjected to force’.

There could be an implied threat of force; in this case the surrounding of the victim by so many created an implied threat.

There could be an implied threat of force; in this case the surrounding of the victim by so many created an implied threat.

In any event, there was some limited force used by holding the victim’s arms and pushing him.

In any event, there was some limited force used by holding the victim’s arms and pushing him.

On any person

This means that the person threatened does not have to be the person from whom the theft occurs. An obvious example is an armed robber who enters a bank, seizes a customer and threatens to shoot that customer unless a bank official gets money out of the safe. This is putting a person in fear of being then and there subjected to force. The fact that it is not the customer’s property which is being stolen does not matter.

14.1.4 Force immediately before or at the time of the theft

The force must be immediately before or at the time of stealing. This raises two problems. First, how ‘immediate’ does ‘immediately before’ have to be? What about the situation where a bank official is attacked at his home by a gang in order to get keys and security codes from him? The gang then drive to the bank and steal money. The theft has taken place an hour after the use of force. Is this ‘immediately before’? It would seem right that the gang should be convicted of robbery. But what if the time delay were longer, as could happen if the attack on the manager was on Saturday evening and the theft of the money not until 24 hours later. Does this still come within ‘immediately before’? There have been no decided cases on this point. The second problem is deciding the point at which a theft is completed, so that the force is no longer ‘at the time of stealing’.

CASE EXAMPLE

Hale (1979) Crim LR 596

Two defendants knocked on the door of a house. When a woman opened the door they forced their way into the house and one defendant put his hand over her mouth to stop her screaming while the other defendant went upstairs to see what he could find to take. He took a jewellery box. Before they left the house they tied up the householder and gagged her.

They argued on appeal that the theft was complete as soon as the second defendant picked up the jewellery box, so the use of force in tying up the householder was not at the time of stealing. However, the Court of Appeal upheld their convictions. The Court of Appeal thought that the jury could have come to the decision that there was force immediately before the theft when one of the defendants put his hand over the householder’s mouth. In addition, the Court of Appeal thought that the tying up of the householder could also be force for the purpose of robbery as it held that the theft was still ongoing.

JUDGMENT

‘We also think that [the jury] were also entitled to rely upon the act of tying her up provided they were satisfied (and it is difficult to see how they could not be satisfied) that the force so used was to enable them to steal. If they were still engaged in the act of stealing the force was clearly used to enable them to continue to assume the rights the owner and permanently to deprive Mrs Carrett of her box, which is what they began to do when they first seized it …

To say that the conduct is over and done with as soon as he laid hands on the property … is contrary to commonsense and to the natural meaning of words … the act of appropriation does not suddenly cease. It is a continuous act and it is a matter for the jury to decide whether or not the act of appropriation has finished.’

So, in this case for robbery, appropriation is viewed as a continuing act or a course of conduct. However, Hale (1979) was decided before Gomez (1993), which is the leading case on appropriation in theft. Gomez (1993) rules that the point of appropriation is when D first does an act assuming a right of the owner. This point was argued in Lockley (1995) Crim LR 656. D was caught shoplifting cans of beer from an off-licence, and used force on the shopkeeper who was trying to stop him from escaping. He appealed on the basis that Gomez (1993) had impliedly overruled Hale (1979). However, the Court of Appeal rejected this argument and confirmed that the principle in Hale (1979) still applied in robbery.

But there must be a point when the theft is complete and so any force used after this point does not make it robbery. What if in Lockley (1995) D had left the shop and was running down the road when a passer-by (alerted by the shouts of the shopkeeper) tried to stop him? D uses force on the passer-by to escape. Surely the theft is completed before this use of force? The force used is a separate act to the theft and does not make the theft a robbery. The force would, of course, be a separate offence of assault.

The point that force must be used ‘immediately before or at the time of stealing was the critical issue in Vinall (2011) EWCA Crim 6252.

CASE EXAMPLE

Vinall (2011) EWCA Crim 6252

Ds punched V causing him to fall off his bicycle. One of the defendants said to V, ‘Don’t try anything stupid, I’ve got a knife.’ V fled on foot chased by Ds. Ds gave up the chase and went back to the bicycle and walked off with it. They abandoned it by a bus shelter about 50 yards from where V had left it.

The trial judge directed the jury that the intention to permanently deprive V of the bicycle could have been formed either at the point in time when the bicycle was first taken or when it was abandoned as this would amount to a fresh appropriation. The jury convicted Ds of robbery. On appeal the Court of Appeal quashed their convictions.

They pointed out that robbery requires proof that D stole and used (or threatened) force either immediately before or at the time of’ stealing and that the force was used in order to steal. It was not possible to know whether the jury had decided that the intention to permanently deprive was formed at the time when the bicycle was first taken or when it was left at the bus stop. If the jury had found that the intention for theft was only formed at the time of abandonment, then there was no robbery. So the convictions were unsafe.

Finally it should be noted that the threat of force in the future cannot constitute robbery, although it may be blackmail.

14.1.5 Force in order to steal

The force must be used in order to steal. So if the force was not used for this purpose, then any later theft will not make it into robbery. Take the situation where D has an argument with V and punches him, knocking him out. D then sees that some money has fallen out of V’s pocket and decides to take it. The force was not used for the pur-pose of that theft and D is not guilty of robbery, but guilty of two separate offences: an assault and theft.

14.1.6 Mens rea for robbery

D must have the mens rea for theft, that is, he must be dishonest and he must intend to permanently deprive the other of the property. He must also intend to use force to steal.

14.1.7 Possible reform of law of robbery

Robbery is a combination of two offences: theft and an assault of some level. The amount of force required is very small. Andrew Ashworth in ‘Robbery Reassessed’ (2002) Crim LR 851 points out that non-fatal offences against the person reflect the amount of force used and suggests that robbery should have at least two levels with different degrees of force. Ashworth also questions whether it is necessary for the offence to exist. Instead of charging robbery it would be possible to charge D with separate offences of theft and the relevant assault.

QUOTATION

‘A more radical proposal would be to abolish the offence of robbery. It would then be left to prosecutors to charge the components of theft and violence separately, which would focus the court’s attention on those two elements, separately and then (for sentencing purposes) in combination. The principle difficulty with this is the absence from English law of an offence of threatening injury: between the summary offence of assault by posing a threat of force, and the serious offence of making a threat to kill, there is no intermediate crime. This gap ought to be closed, and, if it were, there would be a strong argument that the crime of robbery would be unnecessary.’

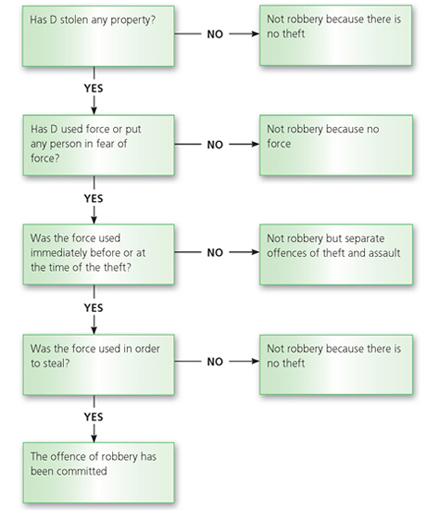

Figure 14.1 Flow chart on robbery

KEY FACTS

Key facts on the factors affecting strict liability

| Element | Law | Case |

| Theft | There must be a completed theft; if any element is missing there is no theft and therefore no robbery. The moment the theft is completed (with the relevant force) there is robbery. | Robinson (1977) Corcoran v Anderton (1980) |

| Force or threat of force | The jury decide whether the acts were force, using the ordinary meaning of the word. It includes wrenching a bag from V’s hand.It does not include snatching a cigarette from V’s fingers | Dawson and James (1976) Clouden (1987) P v DPP (2012) |

| Immediately before or at the time of the theft | For robbery, theft has been held to be a continuing act. Using force to escape can still be at the time of the theft. | Hale (1979) Lockley (1995) |

| In order to steal | The force must be in order to steal. Force used for another purpose does not become robbery if D later decides to steal. | |

| On any person | The force can be against any person. It does not have to be against the victim of the theft. |

ACTIVITY

Applying the law

Explain whether or not a robbery has occurred in each of the following situations.

1. Arnie holds a knife to the throat of a one-month-old baby and orders the baby’s mother to hand over her purse or he will ‘slit the baby’s throat’. The mother hands over her purse.

2. Brendan threatens staff in a post office with an imitation gun. He demands that they hand over the money in the till. One of the staff presses a security button and a grill comes down in front of the counter so that the staff are safe and Brendan cannot reach the till. He leaves without taking anything.

3. Carla snatches a handbag from Delia. Delia is so surprised that she lets go of the bag and Carla runs off with it.

4. Egbert breaks into a car in a car park and takes a briefcase out of it. As he is walking away from the car, the owner arrives, realises what has happened and starts to chase after Egbert. The owner catches hold of Egbert, but Egbert pushes him over and makes his escape.

5. Fenella tells Gerry to hand over her Rolex watch and, that if she does not, Fenella will send her boyfriend round to beat Gerry up. Gerry hands over the watch.

NOTE: See Appendix 2 for an example of how to apply the law of robbery in a problem/scenario type question.

14.2 Burglary

This is an offence under s 9 of the Theft Act 1968.

SECTION

9(1) ‘9 A person is guilty of burglary if —

(a) he enters any building or part of a building as a trespasser and with intent to commit any such offence as is mentioned in subsection (2) below; or

(b) having entered a building or part of a building as a trespasser he steals or attempts to steal anything in the building or that part of it or inflicts or attempts to inflict on any person therein any grievous bodily harm.

(2) The offences referred to in subsection (1)(a) above are offences of stealing anything in the building or part of a building in question, of inflicting on any person therein any grievous bodily harm, and of doing unlawful damage to the building or anything therein.’

As can be seen by reading these subsections, burglary can be committed in a number of ways and the following chart shows this.

KEY FACTS

Key facts on the factors affecting strict liability

| Burglary | |

| Section 9(1)(a) | Section 9(1)(b) |

| Enters a building or part of a building as a trespasser. | Having entered a building or part of a building as a trespasser. |

| With intent to: • steal • inflict grievous bodily harm • do unlawful damage NB used to include intention to rape but this is now covered by s 63 Sexual Offences Act 2003. | • steals or attempts to steal; or • inflicts or attempts to inflict grievous bodily harm. |

14.2.1 The actus reus of burglary

To prove the actus reus of burglary under s 9(1)(a) the prosecution must show that D entered a building or part of a building as a trespasser.

For the actus reus of burglary under s 9(1)(b) it has to be proved that D had entered a building or part of a building as a trespasser and then stolen or attempted to steal or inflicted or attempted to inflict grievous bodily harm.

Although ss 9(1)(a) and 9(1)(b) create different ways of committing burglary, they do have common elements. These are that there must be

entry

entry

of a building or part of a building

of a building or part of a building

as a trespasser

as a trespasser

14.2.2 Entry

‘Entry’ is not defined in the 1968 Act. Prior to the Act, common law rules had developed on what constituted entry. The main rules were that the entry of any part of the body (even a finger) into the building was sufficient and also that there was an entry if D did not physically enter but inserted an instrument for the purpose of theft (for example, where D used a fishing net to try to pick up items). Initially when the courts had to interpret the word ‘enters’ in the Theft Act 1968, they took a very different line to the old common law rules.

The first main case on this point was Collins (1972) 2 All ER 1105 (see section 14.2.4 for the facts of Collins). In this case the Court of Appeal said that the jury had to be satisfied that D had made ‘an effective and substantial entry’. However, in Brown (1985) Crim LR 167, this concept of ‘an effective and substantial entry’ was modified to ‘effective entry’.

CASE EXAMPLE

Brown (1985) Crim LR 167

D was standing on the ground outside but leaning in through a shop window rummaging through goods. The Court of Appeal said that the word ‘substantial’ did not materially assist the definition of entry and his conviction for burglary was upheld as clearly in this situation his entry was effective.

However, in Ryan (1996) Crim LR 320, the concept of ‘effective’ entry does not appear to have been followed.

CASE EXAMPLE

Ryan (1996) Crim LR 320

D was trapped when trying to get through a window into a house at 2.30 am. His head and right arm were inside the house but the rest of his body was outside. The fire brigade had to be called to release him. This could scarcely be said to be an ‘effective’ entry. However, the Court of Appeal upheld his conviction for burglary, saying that there was evidence on which the jury could find that D had entered.

14.2.3 Building or part of a building

The Theft Act 1968 does not define building but does give an extended meaning to it to include inhabited places such as houseboats or caravans, which would otherwise not be included in the offence. This is set out in s 9(4).

SECTION

‘9(4) References … to a building shall apply also to an inhabited vehicle or vessel, and shall apply to any such vehicle or vessel at times when the person having a habitation is not there as well as at times when he is.’

The main problems for the courts have come where a structure such as a portacabin has been used for storage or office work. In a very old case decided well before the Theft Act 1968, Stevens v Gourley (1859) 7 CB NS 99, it was said that a building must be ‘intended to be permanent, or at least to endure for a considerable time’.

This means that the facts of each case must be considered. There are two cases on whether a large storage container is a building. In these cases the court came to different decisions after looking at the facts.

In B and S v Leathley (1979) Crim LR 314 a 25-foot-long freezer container which had been in a farmyard for over two years was used as a storage facility. It rested on sleepers, had doors with locks and was connected to the electricity supply. This was held to be a building.

In B and S v Leathley (1979) Crim LR 314 a 25-foot-long freezer container which had been in a farmyard for over two years was used as a storage facility. It rested on sleepers, had doors with locks and was connected to the electricity supply. This was held to be a building.

In Norfolk Constabulary v Seekings and Gould (1986) Crim LR 167 a lorry trailer with wheels which had been used for over a year for storage, had steps that provided access and was connected to the electricity supply was held not to be a building. The fact that it had wheels meant that it remained a vehicle.

In Norfolk Constabulary v Seekings and Gould (1986) Crim LR 167 a lorry trailer with wheels which had been used for over a year for storage, had steps that provided access and was connected to the electricity supply was held not to be a building. The fact that it had wheels meant that it remained a vehicle.

Part of a building

The phrase ‘part of building’ is used to cover situations in which the defendant may have permission to be in one part of the building (and therefore is not a trespasser in that part) but does not have permission to be in another part. A case example to demonstrate this is Walkington (1979) 2 All ER 716. D went into the counter area in a shop and opened a till. He was guilty of burglary under s 9(1)(a) because he had entered part of a building (the counter area) as a trespasser with the intention of stealing. Other examples include storerooms in shops where shoppers would not have permission to enter or where one student entered another student’s room in a hall of residence without permission.

14.2.4 As a trespasser

In order for D to commit burglary he must enter as a trespasser. If a person has permission to enter he is not a trespasser. This was illustrated by the unusual case of Collins (1972). NB Since May 2004, Collins would be charged with an offence under s 63, Sexual Offences Act 2003.

CASE EXAMPLE

Collins (1972) 2 All ER 1105

D, having had quite a lot to drink, decided he wanted to have sexual intercourse. He saw an open window and climbed a ladder to look in. He saw there was a naked girl asleep in bed. He then went down the ladder, took off all his clothes except for his socks and climbed back up the ladder to the girl’s bedroom. As he was on the window sill outside the room, she woke up, thought he was her boyfriend and helped him into the room where they had sex. He was convicted of burglary under s 9(1)(a), ie that he had entered as a trespasser with intent to rape. (He could not be charged with rape, as the girl accepted that she had consented to sex.) He appealed on the basis that that he was not a trespasser as he had been invited in. The Court of Appeal quashed his conviction, pointing out:

JUDGMENT

‘… there cannot be a conviction for entering premises “as a trespasser” within the meaning of s 9 of the Theft Act 1968 unless the person entering does so knowing he is a trespasser and nevertheless deliberately enters, or, at the very least, is reckless whether or not he is entering the premises of another without the other party’s consent.’

So to succeed on a charge of burglary, the prosecution must prove that the defendant knew, or was subjectively reckless, as to whether he was trespassing.

Going beyond permission

However, where the defendant goes beyond the permission given, he may be considered a trespasser. In Smith and Jones (1976) 3 All ER 54, Smith and his friend went to Smith’s father’s house in the middle of the night and took two television sets without the father’s knowledge or permission. The father stated that his son would not be a trespasser in the house; he had a general permission to enter. The Court of Appeal referred back to the judgment in Collins (1972) and added this principle.

JUDGMENT

‘It is our view that a person is a trespasser for the purpose of s 9(1)(b) of the Theft Act 1968 if he enters premises of another knowing that he is entering in excess of the permission that has been given to him to enter, or being reckless whether he is entering in excess of [that] permission.’

This meant that Smith was guilty of burglary. This decision was in line with the Australian case of Barker v R (1983) 7 ALJR 426, where one person who was going away asked D, who was a neighbour, to keep an eye on the house and told D where a key was hidden should he need to enter. D used the key to enter and steal property. He was found guilty of burglary. The Australian court said:

JUDGMENT

‘If a person enters for a purpose outside the scope of his authority then he stands on no better position than a person who enters with no authority at all.’

The late Professor Sir John Smith argued that this would mean that a person who enters a shop with the intention of stealing would be guilty of burglary as he only has permission to enter for the purpose of shopping. However, it would be difficult in most cases to prove that the intention to shoplift was there at the point of entering the shop.

There are many situations where a person has permission to enter for a limited purpose. For example, someone buys a ticket to attend a concert in a concert hall or to look round an historic building or an art collection. The ticket is a licence (or permission) to be in the building for a very specific reason and/or time. If D buys a ticket intending to steal one of the paintings from the art collection, this line of reasoning would suggest that he is guilty of burglary. However, in Byrne v Kinematograph Renters Society Ltd (1958) 2 All ER 579, a civil case, it was held that it was not trespass to gain entry to a cinema by buying a ticket with the purpose of counting the number in the audience, not with the purpose of seeing the film. This case was distinguished in Smith and Jones (1976) on the basis that the permission to enter a cinema was in general terms and not limited to viewing the film and was very different from the situation where D enters with the intention to steal (or cause grievous bodily harm or criminal damage).

If a person has been banned from entering a shop (or other place), then there is no problem. When they enter they are entering as a trespasser. This means that a known shoplifter who is banned from entering a local supermarket would be guilty of burglary if he or she entered intending to steal goods (s 9(1)(a)) or if, having entered, he then stole goods (s 9(1)(b)).

The law is also clear where D gains entry through fraud, such as where he claims to be a gas meter reader. There is no genuine permission to enter and D is a trespasser.

14.2.5 Mens rea of burglary

There are two parts to the mental element in burglary. These are in respect of:

entering as a trespasser

entering as a trespasser

the ulterior offence

the ulterior offence

First, as stated above, the defendant must know, or be subjectively reckless, as to whether he is trespassing. In addition, for s 9(1)(a) the defendant must have the intention to commit one of the offences at the time of entering the building. Where D is entering intending to steal anything he can find which is worth taking, then this is called a conditional intent. This is sufficient for D to be guilty under s 9(1)(a). This was decided in Attorney-General’s References Nos 1 and 2 of 1979 (1979) 3 All ER 143.

For s 9(1)(b), the defendant must have the mens rea for theft or grievous bodily harm when committing (or attempting to commit) the actus reus of these offences.

14.2.6 Burglary of a dwelling

This carries a higher maximum sentence than burglary of other types of building as a result of an amendment to the Theft Act 1968 by the Criminal Justice Act 1991. Section 9(3) now reads:

SECTION

9(3) A person guilty of burglary shall on conviction on indictment be liable to imprison-i ment for a term not exceeding —

(a) where the offence was committed in respect of a building or part of a building jwhich is a dwelling, fourteen years;

(b) in any other case, ten years.’