Revisiting Credit Risk, Analysis and Policy in Bank Shipping Finance

Chapter 27

Revisiting Credit Risk, Analysis and Policy in Bank Shipping Finance

Costas Th. Grammenos*

1. Introduction

There are three main groups of sources of shipping finance: Equity finance, which includes retained earnings and equity offerings, either public or private;1 mezzanine finance, which encompasses hybrids, such as warrants and convertibles, subordinated debt and preference shares;2 and debt finance, which contains bank loans, export finance, tax leases, private placements (traditional and 144A) and public debt issues.3

This chapter concentrates on bank finance – which is still the largest source of capital in the shipping industry – with particular reference to commercial bank loans. Bank shipping loans are granted to borrowers by a number of different financial institutions, such as: export–import banks; development banks; banks specialising in shipping; and commercial banks. These institutions deal primarily with the major risk – the credit risk (or default risk) – which is the uncertainty over the repayment of the granted loan and payment of its interest, in full, on the promised date.

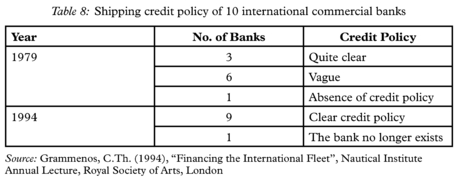

Shipping departments of a sizeable number of commercial banks, or banks specialising in shipping, have seen their profitability fluctuate substantially over the years. Increased profits strengthened the presence of commercial banks committed to shipping, and attracted newcomers. The early 1970s, the late 1980s, part of the 1990s and the second half of the current decade are good examples of high bank shipping profitability stemming from booming shipping markets. However, heavy losses over periods of shipping recession or depression have also been realised and have led a number of banks to abandon the finance of shipping. Here, the mid-1980s is a representative example to abandon ship financing.4

Loan losses may significantly reduce the return on equity (ROE) of a bank and, therefore, destroy value for the bank, or loan profits may increase the ROE and, consequently, create value for the bank.

The rest of this chapter is organised as follows. Section 2 focuses on credit risk, while Section 3 discusses key issues of credit risk analysis. Section 4 deals with collateral securities, including mortgage, assignment of revenue, assignment of insurance and guarantees. Covenants are covered in Section 5, while Section 6 presents a further discussion of credit analysis and issues, such as pricing of the loan, syndication and capital adequacy rules. The focus of Section 7 is loan monitoring; while Section 8 covers shipping credit policy. In Section 9, the conclusions are presented.

2. Credit Risk

The lending function of the bank deals with credit risk, and has four parts:5 the first is the origination of the loan which includes initiation of the loan, analysis, documentation, due diligence and approval; the second is the funding, during which external and/or internal funds are used for the draw-down of the loan; the third is the follow-up part when principal and interest rate payments are made; and the fourth is the monitoring part, which is carried out in parallel with the “follow up” of the loan, through collecting, processing, and analysing data and information regarding the borrower. The objective of the lending function is to create value for the bank, through granting sound loans; and sound loans are the ones which are paid off.

The main risk in bank shipping finance is the credit – or default – risk.6 This is primarily due to the volatility of the vessel’s income, which is the main source of the loan repayment; and the consequent fluctuations in the vessel’s market value which is, in most cases, the main security for the loan.

The financial institutions provide loans of varying forms to shipping companies, the core being the term loan under which the bank lends a certain amount to the shipping company for vessel acquisition over a specific period (above one year), to be repaid normally from the income generated by the vessel(s) to be financed and, possibly, by its/their residual value. The loan is tailor-made to suit the needs of the borrower and the lender, in the particular circumstances.7 Thus, equal or unequal instalments can be arranged and a moratorium for one or two years can be granted, whereby only interest payments are made for a certain period of time, to allow for poor shipping market conditions. Furthermore, a balloon payment can be approved for a loan – that is to say, a large amount of the loan, which reflects the residual value of the vessel (between 25 to 30% of the vessel’s current market value), should be paid with the last instalment. In reality, the balloon payment is usually refinanced for one year or longer – provided the borrower has met his commitment and depending upon the amount of the balloon, the value of the vessel and the freight income of the vessel. In this way, the loan repayment period can be stretched further without the bank committing itself to doing so from the beginning, because the repayment period of the loan would be longer and this would increase further the uncertainty.

The interest rate normally fluctuates and is based on LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate), plus a margin (spread), which represents a significant part of the gross income of the bank from the loan. While the margin is fixed in advance, the LIBOR is renewed periodically, such as every three or six months, in the eurodollar interbank market, should the currency denomination be in dollars.8 Such fluctuating interest rates, if un-hedged, prevent the shipping company and the bank from calculating, with certainty, the future interest payments. In comparison with a fixed interest rate for the entire loan repayment period – a rather infrequent feature in bank shipping loans nowadays – the fluctuating interest rate allows the bank to pass on the interest rate risk to the borrower, whose cost rises with increasing LIBOR or decreases with falling LIBOR.9

During the parts of the lending function the two cooperating parties, the bank and the borrower, may have different goals and division of labour. The bank wants its loan to be paid off and increase its profitability. The borrower wants to make its project a success. For this relationship to be sound, the accuracy and quality of risk analysis of the project is critical. The agency theory10 deals with the two problems that may appear between the banker (as a principal) and the borrower (as its agent) in a relationship that the principal delegates work to the agent. The problems emerge due to asymmetry of information which may exist between the banker and the borrower regarding the project to be financed or already financed. Indeed, the borrower (as an insider) may have more accurate information than the banker in areas such as the financial accounts and the condition of the vessel. These problems are adverse selection and moral hazard. Adverse selection refers to uncertainty regarding the viability of the project; while moral hazard refers to the reliability of the borrower.

A characteristic example of adverse selection is the shipping loan portfolio of a relatively small financial institution, at the end of the 1970s, which consisted almost exclusively of loans extended for the purchases of over-aged vessels, while charging high interest rates. In addition, many of the owners were small with only two or three vessels. When the shipping market conditions deteriorated, from 1982 onwards, the freight income decreased dramatically and was not enough to cover the vessels’ running expenses, let alone the loan repayment. At the same time, the vessel market values had declined to their scrap value, while the vessels had been purchased, at the end of the 1970s, at quite high prices. This particular institution suffered great financial losses from its shipping loans.

Regarding moral hazard: Examples include when a borrower deceives the banker, or change his/her behaviour; false items in the running expenses of vessels; false statements regarding overall net worth; liquidity of the shipping group; or transfer of income from mortgaged vessels to other companies; this may be permissible in some circumstances, e.g. where a corporate guarantee is provided.

The financial institutions, in order to increase their value and also deal effectively with the agency problems, incur certain costs – the agency costs. These are related to – among others – the collection, processing and analysis of data for the loans granted and to be granted. However, one has to keep in mind the very special role of the financial institutions, as intermediaries between savers and users of funds. In this capacity, and due to the limited ability of the savers to obtain and analyse information regarding initial and continuing creditworthiness of the end fund users (borrowers), the financial institutions undertake this role on their behalf. Consequently, the financial institutions have a greater incentive to collect and process this information, due to the large number of savers who appoint them as their “delegated monitors”.11 In so doing, the financial institutions are also protecting the wealth of their shareholders, who are expecting to see it increase. Therefore, the lending function should guard the interests of depositors and shareholders, and increase the value of the bank.

The question that arises now, is, how does a the shipping banker dealing with the credit risk?12

There is an array of tools at the banker’s disposal, to minimise credit risk: credit risk analysis; collateral securities; covenants in the loan agreement and the mortgage; monitoring of the granted loans; and shipping credit policy. These issues will be discussed in the following sections.

3. Credit Risk Analysis

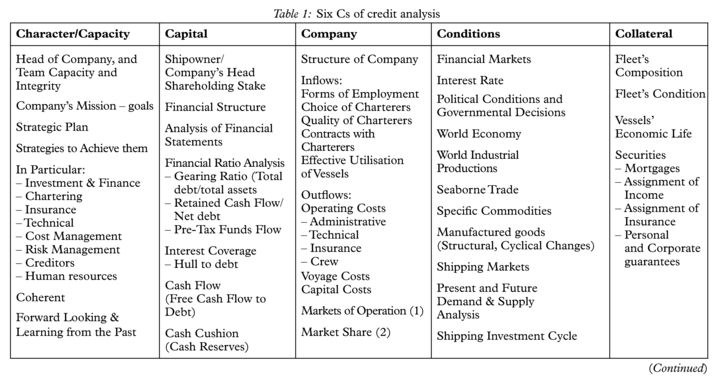

Grammenos13,14 introduced the five “Cs” of Credit in Bank Shipping Finance as a sound credit risk analysis method of assessing the probability of the repayment of the loan proposals for acquisition of secondhand vessels and newbuildings, based on five key words that start with “C”: Character, Capacity, Capital, Conditions, Collateral. “Company” was added at a later date for reasons of clearer presentation. This credit analysis method has been adopted by a large number of financial institutions. Bearing in mind that the interest margin and fees are fixed and, therefore, the upside return of the loan is fixed and the downside risk is substantial, since the loan capital and interest may not be paid as promised, the credit risk analysis of the loan has to assess the probability of their payments in full. Table 1 summarises the main elements of the credit risk analysis that a loan officer has to carry out.

3.1 Character/capacity

The first column of Table 1 concentrates on the head of the shipping company and the management team. Their expertise accumulated over years, their resourcefulness during the lower parts of the shipping cycle, and their integrity, are areas of investigation. The head of the shipping company and his/her team will specify the mission and goals of the company and the strategic plan for their materialisation. They are responsible for designing and applying the strategies to achieve the goals.

The head and team are assessed for their managerial quality as a team and their performance versus plan on strategies over a long period, for instance, over the last two or three cycles or last generation.15 In particular, investment and finance, chartering, insurance, technical, cost management, risk management, creditors, and human resources strategies, are looked at for their overall return to the equity; and whether they managed to decrease costs, increase revenues and profits and create efficiencies. The head’s and team’s “modus operandi”, in comparison with their peers in the same sector, may be useful.

3.2 Capital

The second column refers to Capital. When a shipowner has a relatively large shareholding stake it shows confidence in the company; while the financial structure shows the way the company has been financed. Shipping is a capital-intensive industry, requiring substantial funds primarily, for contracting placement of newbuilding orders; and, secondarily, the purchase of secondhand vessels. All elements in this column are important, but the gearing ratio, the hull (market value) to debt ratio, the net worth and the cash flow, are of paramount importance. A high gearing ratio (debt to total assets) is a double-edged sword: in a flourishing shipping market it may cause the profits and return to equity to soar, in a declining market it may endanger the existence of the company itself.16 Retained cash flow over net debt is calculated after dividend payments and includes the capital component of operating expenses. The higher this measure, the more indicative it is of the ability of the business to generate cash, the availability of cash debt payments or its ability to undertake capital investments. Interest coverage shows how many times operating profit or Earnings before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, Amortisation (EBITDA) covers the interest.17 Hull-to-debt ratio18 is important, not only in a declining or rising shipping market, but also when the time charter, or contract of affreightment ends. It shows the relationship between the loan and market value of the vessel. (See further on this ratio in Section 4.1.)

As long as the bank knows that the real economic net worth – the difference between the market value of assets and the market value of liabilities, as opposed to book value – is positive, then it also knows that the loan is relatively secure. Cash flow is the main source for the loan repayment, while the cash cushion – the existence of accumulated cash from operating profits and/or sale of vessel(s) – is important to cover temporarily interest payments and capital instalments, should the freight market decline.19 In a falling shipping market, other sources of finance – e.g. capital markets – and strong banking relationships may be necessary, hence, an analysis of the different ways that a shipping company is financing its projects and its relationships with different banks is essential. Finally, widely accepted accounting methods such as the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) give the comfort of an international accounting measure, but are not always used by shipping companies; while consolidated audited accounts, despite the fact that they give an overall view of a shipping group, are not always provided by the shipping companies.

3.3 Company

The third column refers initially to the ownership structure of the company. Very often one-vessel companies20 registered in an open registry country, such as Panama, Liberia, Cyprus, Malta, are established and their vessels may be managed by a management company controlled by the shipowner/manager, or owned by a holding company. In the first case, the banker deals with an entity where there is no – or limited – recourse to the management company and the loan is paid by the income and secured by the mortgaged vessel, or some other form of security; while, in the second, he/she deals with a coherent group structure (corporate) that owns a fleet and the repayment of the loan may be only based on the cash flow of the company.

The column then scrutinises sources of income and expenditure. It shows the chartering strategy of the company and the stability – or the vulnerability – of its income. A company with time charters, or contracts of affreightment, has more secured income in comparison with a company that operates its vessels in the spot market, the income of which fluctuates. Bankers and investors are comfortable with the former case, nervous with the latter one. The chartering strategy also reveals the marketing ability of the company; the quality and efficiency of its services; the financial strengths and weaknesses of its charterers; the effective utilisation of the vessels in two, or all, legs of a voyage.

This column also investigates the managerial effectiveness regarding operating and voyage costs. The competitiveness of the company depends not only on its ability to produce income but also how it operates within a competitive budget of costs. However, a record of detentions may indicate costs being cut too much, or insufficient maintenance expenditure. The capital costs are included in this column and, when they are the costs of debt financing, income stability is of paramount importance.21 The last part of this column looks into the market(s), where the company operates, its market share, and the company’s operating position against its competitors.

3.4 Conditions

The fourth column refers to the examination of the competitive and changing international economic, financial and political environment, within which the company makes decisions and operates. The conditions in financial markets; interest rates; the decisions of governments of exporting or importing countries; overall political conditions; developments in the world economy; world industrial production; international and seaborne trade, and the conditions in commodity markets, are issues of utmost importance for shipping markets and companies, since demand for shipping services is a derived one. As Metaxas22 argues: “Vessels carry cargoes and goods that are imports and exports of various countries, the direction and volatility of which have a direct impact on the demand for shipping. Indeed, trade cycles in advanced economies and their resultant international trade cycles affect the magnitude of demand for tramp shipping services and, for this reason, their freight rate movements tend – to a certain degree – to coincide with those of international trade.” Furthermore, structural changes in the above markets, and national economies, may have a more profound and lasting impact on the company’s business than cyclical ones. Examples of these structural changes could be shifts of industrial production from one country to another, which may have an effect on the pattern of shipping trade flows and on the type and size of vessels that are employed or the technological changes that affect the vessel’s efficiency, size and number of crew. Scenario analysis of demand and supply of shipping market(s) where the company operates, with sensitivity analysis, is required for the discussion of their current and future conditions. Volatility in freight rates and vessel market values, that is to say the market risk, is the major parameter for the creation of the loan’s credit risk that the financial institution faces.

Shipping companies operate within a shipping investment cycle, the four stages of which (recovery, boom, recession, depression) are linked with the resultant freight rate as it is established by the demand for – and supply of – vessels.23 When freight rates are high and profits increase, an over-investment in newbuildings is noticed, which may increase the level of supply of vessels and result in an imbalance between supply and demand. In a period of expansion of supply, even a check to the rate of growth of demand will be sufficient to trigger off a downward trend in freight rates. During recession and depression, speculative ordering may take place, often due to subsidised shipbuilding. This lowers the barriers to entry for shipping companies into newbuilding markets and may also prolong the low freight rates. On the other hand, purchase of a vessel, or placing a newbuilding order during this period of low market values, is excellent timing, since this shipowner may compete with vessels bought or ordered during a boom period at high prices.24 Furthermore, the sale of this vessel during a following prosperity phase is very profitable. However, for the banker who undertakes credit risk analysis, stable cash flow is required for the repayment of the loan, not the asset play. In addition, owners may take advantage of low asset costs during a depression but will often be reluctant to mitigate revenue to volatility by fixing a long-term timecharter at the prevailing low rates. It is important for the lending banker to figure out the stage of the shipping cycle, during which it provides finance. Financing over-valued secondhand vessels and newbuildings during a boom period, may result in problematic loans in a period of recession and depression (the comment in endnote 16 is very relevant).

Within the regulatory framework, the International Maritime Organization (the IMO) safeguards the international standards, safety and marine pollution of the shipping industry; flag states, where vessels are registered, impose the regulations of the IMO when they have ratified them; port authorities inspect vessels when they call in; the classification societies supervise the construction, safety and seaworthiness of the vessels during their life; the insurance companies and Protection and Indemnity Clubs deal with the insurance aspects of the vessels; and the major oil companies undertake their own detailed inspections of the tankers that they are going to employ. All these are major parameters for the developments in the shipping regulatory environment which, as time passes, becomes tighter. As such, new investments and their overall cost, sale and purchase market, vessels’ operating expenses, and their revenue, may be seriously affected by the official and corporate regulatory environment. These demand the attention of the banker.

3.5 Collateral

The last column concentrates on the company’s fleet. Its composition is important. Fleet specialisation may develop expertise, operational efficiency and better marketing. However, such a fleet may be vulnerable to market recession. The diversified one, which may offer higher income security, normally requires a larger fleet in operation. The fleet’s condition and the company’s maintenance and repair policy must be taken into account, as often the vessels are the mortgaged assets which produce the (often assigned to the bank) income that repays the loan(s) and they have to be operated safely within the required standards

Apart from the vessel and the mortgage on it, other forms of securities also strengthen the position of the banks: the assignment of income to the bank by which the capital instalments and the interest are paid; assignment of insurance in the case of a casualty or other specific circumstances; corporate guarantees of the holding or management company and personal guarantees of director(s) of the management company, which may cover the bank should the company default in its payment of the loan and/or payment of interest. All forms of security are discussed in Section 4.

3.6 Analysis of cash flow

Having analysed the specific areas of the six “Cs” of credit, the bank has to make a cash flow calculation to ascertain whether the total receipts will cover the total costs of the vessel(s) to be financed, allowing for a balance (cash cushion) sufficient to cover unexpected negative financial developments. The resulting breakeven estimates must be analysed to determine how lucky the vessel is going to need to be in the future spot market to cover its costs. This cash flow estimate25 should be prepared for the proposed acquisition of vessel(s); also, for the group’s fleet with – and without – the proposed acquisitions.

Assessing the stability of the fixed revenue of this statement, and its quality in terms of charterers, requires understanding the legal documents of time charters and contracts of affreightments; and assessing the creditworthiness of charterers.26 While quality of future revenue, based on assumptions, requires an emphasis on the overall creditworthiness of the borrower as revealed through the six “Cs” of credit analysis; and the use of appropriate securities and documentation which is, naturally, the job for the bank’s lawyers. Now, the attention turns to securities and covenants, and credit analysis.27

4. Collateral Securities28

In granting a shipping loan, the bank has three possible areas from which to recoup its funds. The first or “intended” way out is from cash flow generated by the financed acquisition, second, from the mortgage on the financed vessel (“direct” security) and third, from additional securities (“indirect” security). It must be stressed that a bank, by taking securities, does so in the expectation that a problem loan will not develop and that sufficient cash flow will be generated by the project to service the outstanding debt without it being required to enforce its rights on the securities of the loan. The decision to be taken by the financial institution, on the appropriate security or securities, depends upon the individual case of the loan and shipping company to be financed. Among the securities are the mortgage, assignment of revenue, assignment of insurance, mortgagee interest insurance, assignment of requisition compensation, guarantees, comfort letters, cash collateral security, share security and the assignment of shipbuilding contract and refund guarantee. A short analysis follows.

4.1 Mortgage

A mortgage duly registered in the country whose flag the vessel flies, and carrying conditional ownership of the acquired vessel that becomes void when the debt is repaid, is the normal method of providing bank security for vessel acquisitions. Note that the type of mortgage will depend on the legislation applicable in the vessel’s country of registry.

Statutory mortgages originated in the UK and adapted in jurisdictions modelled on the UK legal system, protect the mortgagee’s rights by law. UK legislation29 gives every registered lender or security trustee for group of lenders of a UK ship “the power absolutely to dispose of the ship or share in respect of which he is registered, and to give effectual receipts for the purchase money”. In addition, under UK common law, the mortgagee has the right to take possession of the mortgaged vessel whenever the owner is in default of payment of the principal or interest secured by the mortgage, or creates an event of default under the loan agreement, or when the owner acts in a way which impairs the security of the loan. A preferred mortgage ensures the mortgagee’s right by express provision in the mortgage agreement. It is usually detailed and flexible, while the statutory mortgage only stipulates general conditions.30

The convenience of a mortgage lies in the fact that the shipowner can run the business as a going concern, at the same time giving the mortgagee the following basic rights31 to: take possession of the vessel and operate it or proceed to a jurisdiction for arrest; arrest the vessel; sell the vessel at auction or privately; appoint a receiver to handle the affairs of the vessel; and to assume absolute title of the vessel. All these measures aim at protecting the bank and represent an agreement between the borrower and the lender with respect to vessel maintenance, insurance and operation.

One of the major problems encountered in the area of mortgages is in establishing the vessel’s market value, which represents the value of the bank’s security. The market value can be regarded as the average price at which a willing seller could be expected to make an acceptable offer, at arm’s length, to a willing purchaser on the open market, and is different from a vessel’s fixed insurance value32 or the depreciating book value.33

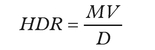

In order to protect against adverse fluctuations in vessel values, banks have attached great importance to the hull-to-debt ratio (particularly when financing single companies):

where, HDR = Hull-to-Debt Ratio

MV = Current Market Value of the Vessel

D = Outstanding amount of the loan (debt)

The hull-to-debt ratio represents the surplus of the market value of the vessel over the outstanding amount of the loan. If this ratio falls below a predetermined level – normally between 120–135%, the bank may require additional security from the borrower. As vessel prices can fall substantially in depressed markets, the availability of additional security may cause serious problems and friction between them. This has happened in the early 1980s and, recently, in 2009–2010. However, many banks accept the realities of depressed shipping markets and remain satisfied as long as loan instalments and interest are paid, so they temporarily freeze the ratio.

Vessels can also be subject to additional second, third, etc. mortgages. A second mortgage is defined as existing when a first mortgage already exists on a vessel. These mortgages lie behind preferred mortgages in creditor ranking and are usually offered as additional security, provided consent of the first mortgagee has been given.

4.2 Assignment of revenue

General assignment of revenue allows present and future revenue from the vessel(s) to be paid directly to the shipowner until an event of default occurs, and reflects the degree of confidence by the lender as to the likelihood of the debt service; while there is another format, the retention account where every month, the owner will transfer a pro-rata proportion of the next amount of interest and instalment from the earnings account to a blocked and pledged retention account with the bank; thus the mortgagee, accumulates the necessary monthly freight revenue to meet the next interest and principal payments.

Under the strict format of specific or legal assignment of revenue, all the specific rights of the borrower arising from a charterparty are assigned to the bank provided the charterer’s consent has been given. Consequently, all charterparty payments are made directly to the bank, which will normally allow the shipowner to withdraw the necessary funds ensuring that the vessel remains operative to service the debt.

The effectiveness of the revenue assignment securities will be directly dependent upon the reliability of the revenue streams, which will in turn be determined by the relevant charterparties. Therefore, the quality, integrity, and financial condition of the charterer in terms of honouring obligations, and the quality of the charterparty itself in terms of drafting and inflation escalation or market adjustment clauses, are particularly important. Furthermore, sub-standard charterparty performance by the owner is often subject to deductions from freight and, as a result, may cause a reduction or cancellation in the level of assigned revenue.

4.3 Assignment of insurance

Insurance coverage is required as an additional security should the vessel be damaged, lost, or subject to a claim from third parties. Insurance protection in shipping finance primarily involves the assignment of all insurance payments due to the borrower, to be paid either directly to the bank or requiring the bank’s express consent before being paid to the borrower, subject to an agreed major claim threshold. Different types of insurance protection are: hull and machinery insurance which protects the bank by ensuring compensation if the vessel is lost or damaged, as does war and strikes cover; the loss of hire or earnings insurance which protects against interruption in cash flow; and other insurance protection important for the bank to ensure cash flow and debt service, include protection and indemnity,34 which covers third-party risks, such as collision liability, loss of life, cargo liability; and freight, demurrage and defence insurance, which provides the shipowner with legal advice and assistance, and covers expenses in pursuing claims and resisting disputes of a more operational nature.

4.4 Mortgagee’s interest insurance

Mortgagee’s interest insurance is an additional insurance which protects the bank in the event of a policy becoming void if certain warranties are broken, (e.g. it covers the interest of the mortgagee in the case of a disputed claim by the underwriters on the grounds of fraud). The mortgagee’s interest claim will usually be withheld, pending the conclusion of litigation. Since this can take some considerable time, and the outstanding loan plus the accruing interest are set at a default rate, the final interest claim may not cover in full the amount due. A solution to this problem is the simultaneous payments of mortgagee’s interest during litigation, subject to return if underwriters are subsequently forced to pay. Alternatively, an escrow interest-bearing account can receive the mortgagee’s interest claim and be subject to release, should the underwriters be compelled to pay.

4.5 Assignment of requisition compensation

This security consists of the borrower assigning to the bank, any compensatory payments in the event of vessel requisitioning, either in terms of absolute title, or for hire purposes during times of war, hostilities or nationalisation.

4.6 Guarantees

A guarantee is an undertaking, given to the bank by the guarantor, to be answerable for the loan and interest granted by the bank to a shipping company, upon the loan becoming defaulted. In accepting guarantees, the bank should also investigate the legal authority of the guarantor to give guarantees. Guarantees are normally personal or corporate.

Under a personal guarantee agreement, the guarantor is liable – on demand – for the discharge of all liabilities to the bank up to the stated amount or proportion, in the event of default on the part of the borrower. The personal guarantee is based on the guarantor’s personal assets which may sometimes be registered in the names of other family members or “offshore” companies. Legal recourse, when necessary, against the borrower and the guarantor, who is usually the owner or major shareholder of the shipping company, is often questionable and difficult. Thus, personal guarantees are now often recognised by the banking sector as being an indication of good faith or moral commitment on behalf of the owner, rather than a cast iron legal security. They are currently out of favour, but they may well return for the family-owned entities.

Corporate guarantees are usually given by the group holding company in conventional structures, or by related management shipping companies in single vessel structures. These guarantees are becoming very important in the latter case, when the security is only the mortgage and the assignment of income. Should a payment default develop, the bank has recourse to the guarantor.

4.7 Comfort letters

Comfort letters are a form of intermediate, less strict, guarantees usually containing assurances and intent.

4.8 Cash collateral security

Cash securities usually comprise a special cash collateral account, blocked by the bank, which may be established on an initial lump sum or monthly payment basis. The reason for their existence is that the bank lowers its loan exposure and also holds cash, which can be used for the payment of interest and repayment of loan instalments should the shipping company be unable to cover them in a falling freight market, during which the vessel may face temporary employment problems. Cash collateral accounts are normally interest-bearing, subject to negotiation.

4.9 Share security

The share security, which is normally taken in addition to the mortgage, consists of the vessel-owning company depositing shares of the borrowing shipping company that he/she controls, with the bank, for a specific period or up to the final amortisation of the loan.