Regulation, Licensing, Education, and Training

2

Regulation, Licensing, Education, and Training

The Path to Professionalism in the Security Industry

Chapter outline

Introduction: The Impetus for Increased Regulation

Professional and Continuing Education

Model Educational Programs: Curricula

Introduction: The Impetus for Increased Regulation

Much needs to be said about the security industry’s call for increased professionalism and standards. Is it merely shallow puffery—calling for respect, skilled personnel, occupational status, and direction without taking the requisite steps to insure that reality? Or is private security following the path to professionalism, insisting on well-regulated personnel, highly proficient in the field’s varied tasks, properly educated, and motivated to continuous training and professional improvement? “Professionalism carries with it certain responsibilities as well as certain privileges.”1

Any quest for professionalism mandates serious licensing requirements and quantifiable standards or levels of personal achievement, education, and experience. Security personnel must be both aware and strictly attentive to the dramatic surge of law and legislation outlining required levels of training and standards. “The private security field is entering a new era—an era of governmental regulation … and training of the guard force is a major focus of this regulatory thrust.”2

The National Private Security Officer Survey, whose respondents included security directors, facilities and plant managers, security executives, and professional organizations, manifests an appreciation for regulation, either of a public or private variety, to ensure a quality workforce.3 Some findings were as follows:

• 75 percent check personal references

• 24 percent use psychological evaluation

• 40 percent use drug screening

• 53 percent believe there will be increased federal regulation of security officers

Governments have not been shy about jumping into the oversight role of the private security industry, and this tendency has heightened since 9/11. A bipartisan bill, the Private Security Officer Employment Standards Act of 2002, sponsored by Senators Levin, Thompson, Leiberman, and McConnell, sought review of past criminal histories of private security personnel. The legislative intent concerning the act is plain on its face:

Congress finds that

1. employment of private security officers in the United States is growing rapidly;

6. the trend in the nation toward growth in such security services has accelerated rapidly;

10. standards are essential for the selection, training, and supervision of qualified security personnel providing security services.5

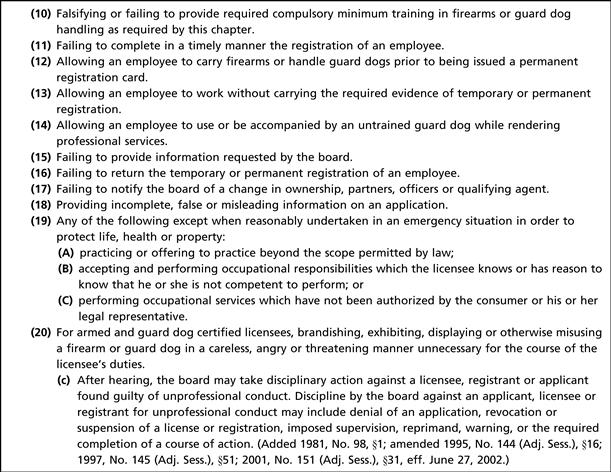

Terrorism alone has justified a new vision of professionalism and corresponding oversight.6 The U.S. State Department paints a grim picture of terrorism’s impact on asset and facility integrity. Terrorism has changed the landscape. Data on numbers of international attacks from 1997 to 2002, shown in Figure 2.1, unfortunately chart an inclined plane with no end in sight.7

Figure 2.1 Total number of facilities struck by terrorist attacks between 1998 and 2003.

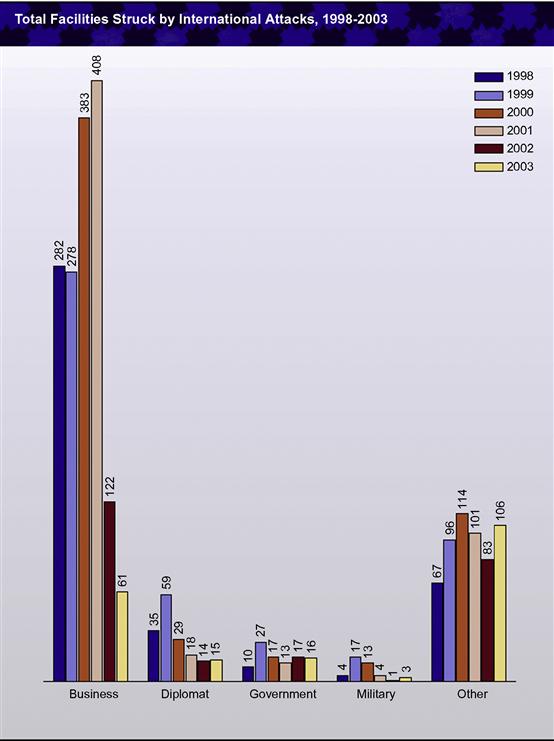

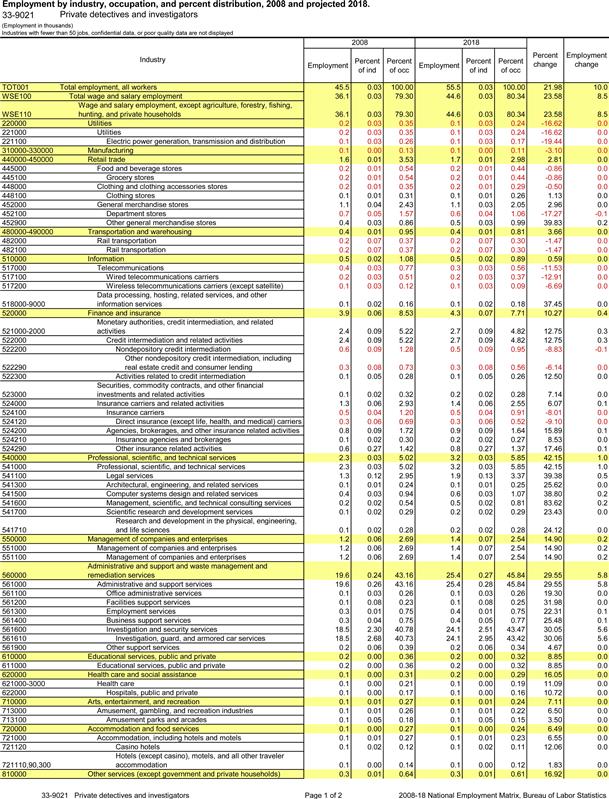

The security industry itself wishes some level of standardization in matters of licensure, regulation, and professional standards. Because private security personnel are increasingly involved in the detection and prevention of criminal activity, use of ill-trained, ill-equipped, and unsophisticated individuals is not only unwarranted but foolhardy. See Table 2.1.8

Table 2.1. Employment by Industry, Occupation & Percent Distribution

|

|

Consider the potential liabilities, both civil and criminal, that can potentially arise from a security employee who has little or no training or has not been diligently screened. J. Shane Creamer, former attorney general for the commonwealth of Pennsylvania, argues decisively:

There is a variety of problems involving abuse of authority which impact society itself. These range from very serious instances in which a private security officer shoots someone to a minor instance of using offensive language. These actions occur in the context of an attempted arrest, detention, interrogation or search by a guard or a retail security officer. There is a striking consistency among private security executives’ views, personal-injury claims statistics, responses of security personnel, complaints recorded by regulatory agencies, court cases, and press accounts. One is led to the inescapable conclusion that serious abuses occur—even if their frequency is unknown.9

Lack of proper standards, training, and educational preparedness results in a predictable shortage of skilled and dutiful security practitioners. Promotion of these traits and professional characteristics could and does curtail a plethora of common private enforcement problems, including the following:

Certainly, state legislatures, federal authorities, and even local governing bodies are mindful. “On the local level governmental regulation dealing with training is proliferating. Cities, counties, and states are contemplating, or have already enacted, legislation or ordinances mandating standards for private security guards within their jurisdiction—standards that rarely fail to include training requirements.”10 Oversight is fairly expected and sensibly demanded of our governmental bodies:

The states have the authority to regulate and license the private security industry, whether private detectives, watchmen, guard services, security agencies or any other activity related to personal and property security. The state may set reasonable standards and requirements for licensing. The courts stand ready to examine the regulations but only when these enactments appear unreasonable, capricious in purpose or arbitrary in design. Furthermore, they stand ready to examine either the uniformity or disparateness of impacts when implementing the regulations.11

The ramifications of inadequate regulation and licensing are far reaching. The 1985 study, Crime and Protection in America: A Study of Private Security and Law Enforcement Resources and Relationships, 12 by the National Institute of Justice, categorized how abuses and unprofessional behavior usually manifests itself in conduct:

• aggressive, unprofessional techniques

• fictitious bidding processes

• high turnover rates (personnel)

• internal fraud and criminal corruption

Even from an industry self-interest point of view, increased standards and regulatory requirements seem to correlate to eventual salary and position. The ASIS International database and study, Compensation in the Security Loss Prevention Field, corroborates the correlation:

The survey serves as a benchmark, confirming what many industry professionals have known: For instance, unarmed security officers rank at the low end of the salary spectrum, with an average income of less than $16,000 a year. The compensation study also highlights some more novel findings, pointing to the Certified Protection Professional (CPP) designation as a distinct factor in higher income.14

Salaries also vary by geographic region and by armed or unarmed status. In 1993, unarmed salaries ranged between $12,000 and $21,000, and salaries for armed security officers ranged between $13,000 and $35,000.15

As the public justice system privatizes further, increased regulation and licensing will occur. Without it, abuse of authority will only escalate. At present, there is no national regulatory consensus to ensure a uniform design, though most states fall into one of these categories:

1. Some jurisdictions have absolutely no regulatory oversight in the private security industry.16

2. Some jurisdictions heavily regulate armed security professionals, but disregard other private security activities.17

3. Some jurisdictions use existing state and municipal police forces to regulate the industry, while others promote self-regulation and education.18

4. Some jurisdictions cover the activities of alarm companies, while others exempt them.

5. Some jurisdictions devise separate regulatory processes for private detectives, but not for security guards or officers, while others make no distinction.19

6. Most jurisdictions have little education or training requirements, though the trend is toward increased education.20

7. Jurisdictions that require examinations for licensing are in the minority.

8. Those that regulate have an experience requirement.

At present, the regulatory climate is a hodgepodge of philosophies exhibiting increasing uniformity. Moreover, regulation at the state and local levels has often been hastily developed and quickly enacted following the media accounts alleging abuses of security guards’ powers and the commission of criminal actions by the guards.21 Usually, one hears about the regulatory crisis when scandal erupts or some criminality occurs within the security community. It is indisputable that there is a linkage between the behavior, good or bad, and the level of regulatory requirements and oversight in the security industry. More effective licensing and regulation for the private security industry can be attained by statewide preemptive legislation and interstate licensing agency reciprocity. With the number of national private security companies, the legislatures must address these two critical components of the licensing and regulation process. In states with a proliferation of local licensing ordinances, legislatures must take a leadership role in establishing uniform and fair legislation.

In addition, states must enter into interstate licensing reciprocity similar to that used by public law enforcement agencies in such matters as auto licenses, driver’s licenses, and similar regulation. Currently, the national security companies are required to be licensed in many states. This is not cost effective either for the security companies or ultimately the users of security services. Many smaller security companies that operate in several jurisdictions in adjacent states experience the same burden.22

Given these dynamics, a call for professionalism both from industry sources as well as governmental entities has been continuous and steadfast, and there are signs of significant progress. At both the federal and state level, the push is on for increased controls, but our examination will weigh these questions:

As the security industry takes on higher levels of responsibility in the elimination of crime, the enforcement of law, and the maintenance of the community, legislation and regulatory policy can only accelerate.

Federal Regulation

Aside from the states’ efforts to professionally regulate the security industry, the federal government, through both direct and indirect means, has had some input into this industry’s current standing. Historically, private security’s union/business activities, from the Molly Maguires to the Homestead Steel Strike, have forced national scrutiny of the industry.23 Recent events of paramilitary security contractors engaged in covert activities in the Middle East, especially in Iraq and Afghanistan only heighten this penchant for oversight. Through the opinions of the U.S. attorney general and congressional passage of the Anti-Pinkerton acts, private security has been the subject of continuous governmental oversight.24

The administrative agencies of the federal government, who extensively contract out for private security services, also influence private sector qualifications through their numerous requirements. These regulatory agencies have set standards on age, experience, education, and character:

• Department of Homeland Security

• Federal Aviation Administration

• Interstate Commerce Commission

• Nuclear Regulatory Commission

• Securities and Exchange Commission

• Food and Drug Administration

• Office of the Inspector General

Federal legislation that impacts on private security practice is another means of regulatory control. Throughout the Clinton and Bush years, and certainly since the debacle of 9/11, various bills have been proposed to nationalize and standardize the security industry and its practice. In reaction to terrorism, Congress has enacted a host of measures that deliver security services in many contexts.26 The Homeland Security Act of 2002 27 signifies a major reorientation in the legislative landscape. The mission of the Homeland Security Agency notes, “In technology and safety, rules and facilities practices, the security world has been turned on its head.”28 In addition, there is an expectation that private security companies and corporations will be active, cooperative players in the defense of a nation as to terror. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) promotes the integration of private sector security firms working in conjunction with public law enforcement. More specifically, DHS erected a Private Sector Office and Outreach Group dedicated to these ends.29

The federal system entangles itself in all sorts of activities prompted by laws and legislation. Data collection, information gathering, and its maintenance are often the subject of federal legislation such as the following:

Polygraphs have also been the subject of congressional oversight with the passage of the Polygraph Protection Act of 1980 31 and the Employee Polygraph Protection Act.32 With extensive limitations on pre-employment screening and further encumbrances on internal investigations, employees and polygraph vendors see little promise in the future role of the polygraph,33 yet the statutes manifest a federal nervousness about the industry.

There is momentum for increased regulation, particularly since the terrorist attacks of 2001. At the federal level, The Law Enforcement and Industrial Security Cooperation Act of 1996 (H.R. 2996)34 was introduced, though it was not passed. H.R. 2996 encouraged cooperation between the private and public sectors. If passed, this bill would have been a solid step for the security industry to take toward an active role in opening the lines of communication with law enforcement and in turn, sharing ideas, training, and working in conjunction with each other, all indirectly influencing standards. The content of the proposed bill is instructive and certainly foretells an active future for the security industry. The rationale for bill adoption is fourfold:

2. There are nearly three employees in private sector security for every one in public law enforcement.

3. More than half of the responses to crime come from private security.

4. A bipartisan study commission specially constituted for the purposes of examining appropriate cooperative roles between public sector law enforcement and private sector security will be able to offer comprehensive proposals for statutory and procedural initiatives.35

The Private Security Officer Employment Standards Act of 200236 represents formidable federal involvement.

The impetus for federal legislation is real and forceful. So much of what the industry does has grave consequences. Technical and electronic intrusions into the general citizenry, especially in the age of computers, raise many concerns. The private security industry must be attuned to legal and human issues that involve privacy. The industry must adopt policies and practices that achieve “a delicate balance between the forces of liberty and authority—between freedom and responsibility.”37

State Regulation

Few would argue the enhanced trend toward regulation. Even police organizations such as the International Association of Police Chiefs (IACP) have promulgated minimum standards. All private security officers must meet the applicable statutory requirements and the established criteria of the employer, which may exceed minimum mandated requirements. Federal law mandates that candidates for employment must be citizens or possess legal alien status prior to employment. All applicants who are hired or certified as a private security officer should meet the following minimum criteria:

A. Be at least 18 years of age—“unarmed” private security officer.

C. Possess a valid state driver’s license (if applicable).

G. Successfully pass a recognized preemployment drug screen.

Suggested nonregulated preemployment applicant criteria include the following:

A. High school education or equivalent;

B. Military discharge records (DD 214);

C. Mental and physical capacity to perform duties for which being employed;

D. Armed applicants shall successfully complete a relevant psychological evaluation to verify that the applicant is suited for duties for which being employed.38

An overwhelming majority of American states have passed legislation governing the security industry. This legislation promulgates standards on education and training, experiential qualifications, and personal character requirements.

That the power to regulate is quite extraordinary is indisputable. The grant or denial of a license has economic and professional implications and regulatory authority must be attentive to due process and constitutional challenges. Most case law reviews not the constitutionality of the regulatory power, but the procedural rules and due process that accompany the industry’s oversight. Appellate cases that challenge the process of oversight are fairly common. In Moates v. Strength,39 an appeals court granted summary judgment to the licensing authority because the appellant was incapable of showing a disregard for procedural regularity. The court noted, “The court cannot recognize a party’s subjective belief that wrongdoing will occur as a viable claim for deprivation of that party’s civil rights.”40

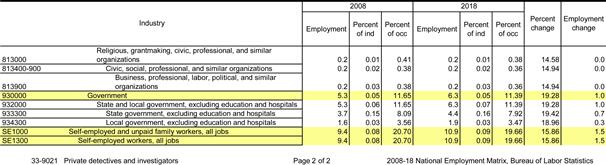

Although it is not the function of this section to review each and every piece of legislation promulgated by the states, the reader will be provided with a broad-based overview of legislative trends and standards. To commence, review the complete Florida Act given in Appendix 1. In Florida, as in most jurisdictions, state legislation tends to emphasize these regulatory categories:

Age

Age and its relation to eligibility are evident in most regulatory frameworks. Does age provide any assurance of better performance, ethical adherence, and professional demeanor? When one considers the seriousness of many security tasks, it seems logical that age is a crucial factor in licensing and regulation. Connecticut’s statutory provision is a case in point:

The applicant for a private detective or private detective agency license shall be not less than twenty-five years of age and of good moral character and shall have had at least five years’ experience as a full-time investigator, as determined in regulations adopted by the commissioner pursuant to section 29-161, or shall have had at least ten years’ experience as a police officer with a state or organized municipal police department.41

Most states are less rigorous than Connecticut, though age is usually a factor according to the type of license applied for. In many jurisdictions, age limitations are outlined when applying for a private investigator’s license:

Hawaii—Be not less than eighteen years of age;42

Indiana—Is at least twenty-one (21) years of age;43

Delaware—Be at least 25 years of age;44

More typically, state legislatures propose minimal age requirements. Iowa makes a qualification for a license conditional on being at least 18 years of age.46 Other jurisdictions following the 18-year-old rule for numerous licensed positions in security include Maine47 and Georgia.48 All in all, most jurisdictions allow applicants to be admitted at the legal age of majority.

Experience Requirements

A majority of states have an experience requirement, a fact somewhat inconsistent with the age qualifications. North Carolina experience provisions are more stringent than most states:

Experience Requirements/Security Guard And Patrol License

Requiring experience in justice-related occupations seems the norm. Georgia’s experience requirements represent this tendency

(3) The applicant for a private detective company license has had at least two years’ experience as an agent registered with a licensed detective agency, or has had at least two years’ experience in law enforcement, or has a four-year degree in criminal justice or a related field from an accredited university or college; and the applicant for a security company license has had at least two years’ experience as a supervisor or administrator in in-house security operations or with a licensed security agency, or has had at least two years’ experience in law enforcement, or has a four-year degree in criminal justice or a related field from an accredited university or college;50

The Georgia legislature allows police and law enforcement training as a substitute for the experience requirement. Other substitute activities for the experience requirements are as follows:

Course work that is relevant to the private investigation business at an accredited college or university;51

Service as a magistrate in this state; or

Any other substantially equivalent training or experience;52

an internal investigator or auditor while making an investigation incidental to the business of the agency or company by which the investigator or auditor is singularly and regularly employed;54

The emphasis placed on experience is a positive sign in the industry’s quest for professionalism. Inept and inexperienced persons should not be entrusted with the obligations of private security. This trend toward security professionalism is further evidenced by the statutory reciprocity that exists between public and private justice, namely credit granted for law enforcement experience, or a waiver of the experience qualifications for those who have served in public law enforcement. Hawaii’s statute is typical of this reciprocity:

Experience requirements. The board may accept the following:

…

(4) Have had experience reasonably equivalent to at least four years of full-time investigational work;55

While great strides are evident in the jurisdictional experience rule, many states blatantly disregard the experience issue. Kansas lacks experience requirements:

75-7b05. License, initial or renewal; fee set by attorney general.

(b) In addition to the application fee imposed pursuant to subsection (a), if the applicant is an organization and any of its officers, directors, partners or associates intends to engage in the business of such organization as a private detective, such officer, director, partner or associate shall make a separate application for a license and pay a fee in an amount fixed by the attorney general pursuant to K.S.A. 2008 Supp. 75-7b22, and amendments thereto.56

Equally silent on experience is New Jersey.57

Licensure

Regulation by license is the state’s effort to regularize security practice and its particular positions. By overseeing occupations and professions, from lawyers to security officers, the state gives credence to the field’s influence and importance and symbolizes a need to quality control those engaging in its activities. Review the Private Detective, Private Alarm, Private Security, and Locksmith Act of 2004.58 Licensure classifications include the following:

Varying degrees of experience, education and training, bond, and age are cited, depending on the license desired. Not surprisingly, the licensure requirements impose the heaviest burdens on those who can exert force, handle weaponry, or own and operate a security agency.