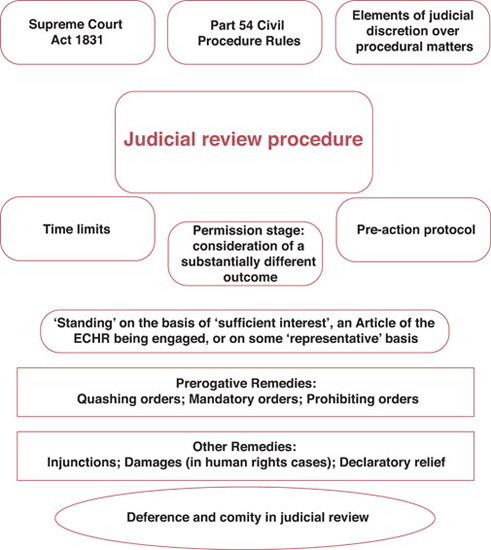

PROCESS, STANDING AND REMEDIES IN JUDICIAL REVIEW

13

Process, standing and remedies in judicial review

13.1 Procedural requirements in applying for permission for judicial review

13.1.1 The procedural basis for judicial review is found in the:

- • Supreme Court Act 1981; and

- • Civil Procedure Rules (Part 54)

13.1.2 Both of these set out procedural requirements in relation to judicial review – the key elements of which are set out in this chapter.

13.1.3 Claims for judicial review are made to the Administrative Court and have two main stages:

- • the permission stage (request for leave); and

- • the substantive hearing.

13.1.4 Prior to the permission stage there is the pre-action protocol whereby the applicant is to write to the body identifying the issues and the body is to reply. Because this process can ensure a settlement, thereby removing the need for litigation, the court will usually expect the parties to comply with it. The procedural requirements are then as follows.

13.1.5 The Supreme Court Act 1981, section 31 states that ‘no application for judicial review shall be made unless the leave of the High Court has been obtained’.

13.1.6 The requirement of leave, or permission, acts as a filter to remove unmeritorious claims.

13.1.7 Judicial review is therefore not available as a right since it is discretionary on the acceptance of the court.

13.1.8 Prior to 2000, leave was previously sought ex parte (without the other side) but it is now inter partes so the court is aware of both sides of the argument.

13.1.9 This part of the process is mostly based on written submissions, though the court may convene an oral hearing.

13.1.10 In early 2015, the Coalition Government sought to limit the number of cases which proceeded to hearings in the judicial review process by making it harder to obtain leave/permission – purportedly out of concern that the growth in judicial review cases over a period of decades has been very great; and that this level of regular scrutiny of the work of Government in the courts has been something that has stalled or slowed the progress of efficient government. This argument, that the courts should be respectful of the work of Government, and the difficulties and pressures Governments face to implement policies in the face of strong public opposition, has been scathingly called ‘the tyrant’s plea’ by Timothy Endicott.

13.1.11 The effect of section 84 of the Criminal Justice and Courts Act 2015 is to create a new test for leave/permission. This is a determination by the court as to whether there would be the ‘highly likely’ outcome of no ‘substantial difference’ following judicial review, if a hearing were to take place.

13.1.12 If it is highly likely that there would be no substantial difference in the eventual action or decision by the public body concerned, even if there were a judicial review hearing in which the claimant were successful, then there will be no leave/permission granted for judicial review, therefore.

13.1.13 When these reforms were passing through Parliament as the Criminal Justice and Courts Bill, there was much criticism that this legislation was an attempt by the Government to reduce the scrutiny that judicial review claims put upon the Government itself.

13.2 The pre-action protocol in relation to claims for judicial review

13.2.1 Parties as the claimants seeking judicial review are expected engage with the pre-action protocol, prior to filing their claim for judicial review.

13.2.2 This is not a strict requirement, however. For one thing, it may be too late for the claimant to follow the pre-action protocol and still comply with the expected time limit to bring their claim (see 13.3).

13.2.3 The pre-action protocol is in essence the supply of a draft claim form to the defendant, along with the factual details underpinning the claim, as the claimant understands them.

13.2.4 This gives the defendant an opportunity to resolve the issue with the claimant without the need for the claim to even reach the High Court. It also allows the defendant to clarify any pertinent factual issues, or dispute them, with regard to the claimant’s version of events.

13.3 Time limits

13.3.1 Under the Civil Procedure Rules 1998, rule 54.5, an action (filing of the claim form) must be brought ‘promptly’ and in any event no later than three months after the grounds to make the claim first arose (rule 54.5(1)(b)).

13.3.2 This may be reduced by statute in specific areas (see above). Conversely, it may also be extended by the court at its discretion.

13.4 ‘Sufficient interest’ standing

13.4.1 Section 31 of the Supreme Court Act 1981 provides that ‘the court shall not grant leave… unless it considers that the applicant has a sufficient interest in the matter to which the application relates’. Sufficient interest is also known as locus standi or standing.

13.4.2 Sufficient interest will be assessed by the court at both the leave stage and at the substantive hearing: R v Inland Revenue Commissioners, ex parte National Federation of Self-employed and Small Businesses (1982).

13.4.3 The need for sufficient interest prevents what Lord Scarman described in the above case as ‘abuse by busybodies, cranks and other mischief makers’. It therefore ensures cases are genuine and avoids unnecessary interference with administrative decisions and processes.

13.4.4 Applicants for judicial review are generally of four types:

- • individuals whose personal rights and interests are affected by a decision;

- • individuals concerned that a decision has affected the interests of society as a whole;

- • pressure or interest groups who believe a decision affects the rights or interests of their members or society as a whole; and

- • individuals claiming for judicial review for a breach of human rights under the Human Rights Act 1998.

Individual personal ‘sufficient interest’

13.4.5 This will depend on the facts of the case and is determined by the court exercising its discretion. It will be relatively easy to establish sufficient interest if the individual is directly or indirectly affected by the decision. There will, for example, be clear indication of sufficient interest if a person’s property or livelihood will be affected.

13.4.6 Some examples of individual personal sufficient interest include:

- • An individual being excluded the right to enter the country (Schmidt v Secretary of State for Home Affairs (1969)); and

- • a traveller trying to ensure his local authority provided an adequate site for him as required by statute (R v Secretary of State for the Environment, ex parte Ward (1984)).