PROCEDURAL GROUNDS FOR JUDICIAL REVIEW

15

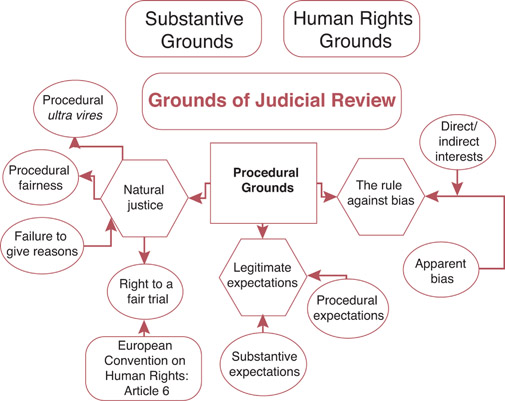

Procedural grounds for judicial review

15.1 An overview of procedural grounds for judicial review

15.1.1 Lord Diplock in the GCHQ Case (discussed above) described procedural impropriety as ground of judicial review to include ‘the failure to observe basic rules of natural justice or failure to act with procedural fairness’ and also ‘failure… to observe procedural rules expressly laid down in… legislative instrument’.

15.1.2 This chapter considers the different procedural grounds that taken as a collective whole can be said to encompass the fuller concept of procedural impropriety.

15.2 Natural justice

15.2.1 The origin of the ‘natural justice’ principles of procedure is found in the common law. They effectively require a public body to act fairly.

15.2.2 With the passing of the Human Rights Act 1998, Article 6 of the ECHR, which requires ‘a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal established by law’, is now enforceable in English courts.

The right to a fair hearing (audi alteram partem)

15.2.3 Traditionally the courts would only apply the right to a fair hearing to judicial decisions: Local Government Board v Arlidge (1915).

15.2.4 In Ridge v Baldwin (1964), however, it was concluded that irrespective of whether a decision is judicial or administrative there is, in principle, a right to be heard. Judicial proceedings will attract a higher procedural standard of the right to a fair hearing than administrative decisions.

15.2.5 One exception to the right to be heard is where there are overriding factors in the interests of national security: GCHQ Case (above). (See also R v Secretary of State for Transport, ex parte Pegasus Holdings Ltd (1989).)

15.2.6 Failure to permit a hearing may also not invalidate the decision when the court concludes that the outcome of the decision would have been the same regardless. For example, in Glynn v Keele University (1971) the court dismissed an application by a student against their expulsion from the university on the basis that no representation by them would have affected the decision.

15.2.7 Whether a hearing is itself fair is not subject to fixed requirements, although the more serious the consequences for the individual, the higher the standard required for the hearing to be fair.

15.2.8 A fair hearing could require one or more of the following requirements therefore, depending on the facts of the case:

- • notification of a hearing/advance notice;

- • to be informed of the case against;

- • the opportunity to respond to evidence;

- • an oral hearing;

- • legal representation before and at the hearing; and

- • the ability to question witnesses.

- • legal representation before and at the hearing; and

15.2.9 For example, there is no absolute right to an oral hearing. According to R v Army Board of the Defence Council, ex parte Anderson (1992), whether an oral hearing is required for the hearing to be fair will depend on the subject matter and circumstances of the particular case. Consequently the question is whether any written proceedings are sufficient to ensure a fair hearing.

15.2.10 Arguments that an oral hearing is an entitlement of a person who may be deprived or may continue to be deprived of a fundamental right, such as their liberty, will be well received by the courts however: see Osborn v Parole Board (2013). The right to cross-examine any witnesses will only arise if there is an oral hearing.

15.2.11 Similarly, the right to legal representation will depend on the nature of the hearing and the rights that will be affected. In R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex parte Tarrant (1985) the criteria to be applied in determining whether legal representation is necessary include:

- • the seriousness of the charge and potential penalty;

- • whether any points of law are likely to be raised;

- • the ability of the person to present their own case;

- • the complexity of the procedure to be applied; and

- • whether there is need for reasonable speed in making the decision.

15.2.12 There does, however, appear to be no such discretion when the matters are ‘criminal’ – for example, in Ezeh v UK (2002) a prison governor’s decision not to allow legal representation at a disciplinary hearing was a breach of the right to a fair trial (Article 6 ECHR).

15.3 Bias: the rule against bias (nemo judex in causa sua)

15.3.1 Impartial and independent decision-making is a fundamental aspect of the rule of law.

15.3.2 The rule against bias is described as being strict in that the risk or appearance of bias will suffice. As stated by Lord Hewart in R v Sussex Justices, ex parte McCarthy (1924), ‘justice must not only be done but must manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done’.

15.3.3 If a decision-maker becomes aware that they may be biased, they should remove themselves from the decision-making process: AWG Group v Morrison (2006).

15.3.4 A financial interest, however small, will automatically indicate bias: Dimes v Grand Junction Canal Co. (1852) and Metropolitan Properties Co v Lannon (1969).

15.3.5 This principle, of automatic disqualification because of a direct interest, was extended in R v Bow Street Metropolitan and Stipendiary Magistrate, ex parte Pinochet Ugarte (1999). In this case extradition proceedings were challenged on the basis that Lord Hoffmann had links with Amnesty International, which had provided evidence. Whilst there was no evidence of actual bias, it was concluded that there could be the appearance of bias and therefore the case was re-heard. The House of Lords stated that any direct interest whether financial, proprietary or otherwise would lead to automatic disqualification.

15.3.6 In other instances, where there is no direct personal interest but a non-direct interest that may give the appearance of bias, the court will examine whether in the view of a ‘fair minded and informed observer’ taking into account all the circumstances there is a ‘real possibility’ of bias: Porter v Magill (2002).

Failure to give reasons as a potential ground of judicial review?

15.3.7 Numerous statutes impose a duty to provide reasons. For example, there is a duty to give reasons on request in tribunals and public inquiries: Tribunals and Inquiries Act 1992.

15.3.8 There is no absolute duty to give reasons under the common law rules of natural justice, although there is a strong presumption that they should be provided: R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex parte Doody (1993).

15.3.9 There have been developments in the common law though where reasons must be provided. These include, for example:

- • Where decisions are analogous to those of a judicial body: R v Civil Service Appeal Board, ex parte Cunningham (1991) and R v Ministry of Defence, ex parte Murray (1998).

- • Where the decisions involve very important interests so that the individual would be at a clear disadvantage if reasons were not provided. For example, in ex parte Doody (above) reasons were required as the applicant otherwise had no knowledge of the case against them; the decision at hand was the fixing of a minimum sentence for a life prisoner (see also Stefan v General Medical Council (1999)). In R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex parte Fayed (1997) the court ruled that some indication of the Home Secretary’s objections to the application for a British passport should have been given.

- • Where the decision is unusual or a severe penalty can be applied. For example, in R v DPP, ex parte Manning (2000) reasons should have been provided for the decision not to prosecute after a coroner’s finding of unlawful killing.

15.3.10 Conversely, there are situations where there will be no duty to provide reasons. This may occur where to do so would be extremely costly or particularly onerous on the decision-maker, or where the reasons for a range of potential decisions are laid out in advance of a final decision by the decision-maker: see R v Higher Education Funding Council, ex parte Institute of Dental Surgery (1994) and R (Asha Foundation) v Millennium Commission (2003).

15.3.11 Where a Minister fails to provide reasons for a decision, the court may infer that there were in fact no proper reasons for that decision: Padfield v Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (1968).

15.3.12 Where reasons are required, they must enable the parties to understand the basis for the decision, but this does not necessarily mean they have to be detailed or comprehensive. The level of detail necessary will depend on the facts of the case: South Buckinghamshire DC v Porter (2004).

15.3.13 Article 6 of the ECHR does not explicitly require the giving of reasons. However, it could be implied because of the need to have reasons in order to be able to exercise any right to appeal. Article 5 of the Convention, however, expressly states in the context of the right to liberty and security that arrested persons shall be informed promptly and in a language they understand of the reasons for their arrest.

15.4 Legitimate expectations

15.4.1 Legitimate expectation is a well-accepted principle of EU law, and has been increasingly recognised by the English courts. It occurs when the decision-maker, by either their words or actions, creates a reasonable and therefore legitimate expectation that certain procedures will be followed in reaching a decision.

15.4.2 If such expectations have been created, the decision-maker is not able to ignore them when coming to a decision on the matter unless there are good reasons not to do so: R (Nadarajah) v Secretary of State for the Home Department, R (Abdi) v Secretary of State for the Home Department (2005).

15.4.3 Whether a legitimate expectation has been created will depend on the circumstances. According to Lord Diplock in the GCHQ Case (above) a legitimate expectation may arise in two circumstances:

- • from either an express promise given on behalf of the decision-maker; or

- • from the existence of a regular practice that the applicant can reasonably expect to continue.

15.4.4 For a promise to create a legitimate expectation it must be clear, unambiguous and precise: R v Inland Revenue Commissioners, ex parte MFK Underwriting Agents Ltd (1990). However, the individual does not have to be aware of it, since it is the decision-maker who should be aware of any expectation created: R (Rashid) v Secretary of State for the Home Department (2005).

15.4.5 Some examples of where there was a clear, unambiguous and precise promise, creating a legitimate expectation, include:

- • R v Liverpool Corporation, ex parte Liverpool Taxi Fleet Operators Association (1972) – the Corporation had given an express representation that licences would not be revoked without prior consultation. This created a legitimate expectation which could be relied on when the Corporation then failed to carry out that consultation.

- • Attorney-General for Hong Kong v Ng Yuen Shiu (1983) – it was concluded that an illegal immigrant had a legitimate expectation of an interview prior to deportation and for his case to be considered on its individual merits because of an express undertaking given by the British Government.

- • R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex parte Asif Mahmood Khan (1984) – the issuing of a circular providing the criteria under which a child would be permitted entry into the United Kingdom was held to have created a legitimate expectation that those criteria would be applied.

- • R (Bibi) v Newham LBC (2001) – it was held that promises made by the local authority had created a legitimate expectation that the applicants (refugees) would be provided with accommodation with security of tenure.

15.4.6 Examples of where the promise was not considered sufficiently clear, unambiguous and precise enough to create a legitimate expectation include:

- • R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex parte Behluli (1998) – the applicant argued that in the case of their expulsion they had a legitimate expectation that the Dublin Convention would be applied. The court held that the statements being relied upon did not create a sufficiently clear intention on behalf of the Government to create a legitimate expectation.

- • R v DPP, ex parte Kebeline (1999) – four applicants sought to rely on a legitimate expectation that the DPP would exercise its discretion to prosecute only in accordance with the ECHR. They based their argument on the ratification of the Convention by the Government; the enactment of the Human Rights Act 1998; and from public statements made by Ministers. However, the Act whilst passed had not yet come into force. The court concluded that no legitimate expectation had been created.

- • R v Secretary of State for Education and Employment, ex parte Begbie (2000) – a Labour Party pre-election promise that children benefiting from the assisted-places scheme would continue to receive this until the end of their education was held not to create a legitimate expectation. This was because Labour was in opposition at the time the statement was made and could not know of all the complexities of the matter until in office; consequently the promise was unclear. Thus, as a consequence of this decision, a pre-election promise cannot bind a new Government.

15.4.7 It should be noted that a legitimate expectation cannot arise from a promise or representation that is unlawful: R v Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, ex parte Hamble (Offshore) Fisheries Ltd (1995) and R (Bibi) v Newham LBC (2001).

15.4.8 The question of whether there is an enforceable legitimate expectation is more complex when it involves a situation where there has been a change of policy.

15.4.9 Whilst legitimate expectation as a ground for judicial review promotes certainty and trust in executive authority, thus upholding the rule of law, it must also be recognised that the executive must be able to develop, adapt and change policies particularly if in the public interest.

15.4.10 In North and East Devon Health Authority, ex parte Coughlan (1999) the Court of Appeal identified three such situations involving legitimate expectation:

- (a) Where a body changes policy, it should consider previous policy and representations made, before changing that policy. Thereafter, in cases of claims of legitimate expectation, review will take place on the basis of whether the decision is Wednesbury unreasonable (see above). For example, R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex parte Hargreaves (1996) – there was an agreement between prisoners and prison authorities that, subject to good behaviour, prisoners could apply for home leave after serving one-third of their sentence. The Home Secretary then changed this to having served half of the sentence. The court held that the agreement did not give rise to a legitimate expectation and that in any case the Home Secretary’s change of policy was reasonable.

- (b) If there is a legitimate expectation of being consulted prior to a decision (a procedural legitimate expectation), the court will examine closely any change in that policy to ensure that any decision is made fairly. For example, in R v Secretary of State for Health, ex parte US Tobacco International Inc. (1992) the company, using a Government grant, opened a factory in 1985 producing snuff. In 1988 the Government was provided with additional evidence of the health risks of snuff and decided to ban it. It was held that whilst there was a legitimate expectation created by the Government’s prior actions, that expectation could not override the need to change the policy in the public interest.

- (c) Where undertakings, representations or promises by a decision-maker create a substantive legitimate expectation, the court will very closely examine any change of policy. The court will balance carefully the interests of fairness given the individual’s legitimate expectation against any overriding need to change the policy in the public interest. For example, in R v North and East Devon Health Authority, ex parte Coughlan (1999) the applicant lived in a home for the severely disabled and had been told by the Health Authority that it would be her home for life. She was then informed that the home was to be closed and she would be transferred. The court held that a legitimate expectation had been created, which no public-interest factor could override.