Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSH Act)

- Employer has a duty to provide a safe workplace—not just to comply with specific safety standards.

- The act provides for highly protective toxic materials standards—but OSHA’s rulemaking has been frustrated by a heavy burden of proof and other problems.

- Worker Right-to-Know: Thorough, understandable, and accessible information about chemical hazards must be provided to workers.

- Protection of whistleblowers against retaliation by employers.

During World War I, the US Radium Corporation of East Orange, New Jersey, produced luminous watches for the US Army for use by soldiers. The numerals were hand-painted on the watch dials by a factory of eighty young women and girls. This was a painstaking process. The workers used tiny camel-hair paintbrushes. They were taught to use their lips to keep a fine point on the brush. Unfortunately, the paint contained radium—that’s what made it glow in the dark. As they “pointed” their brushes, the workers were exposed to radium, a carcinogen.

By the early 1920s, these young workers began developing bone cancer and radium necrosis (also called radium jaw) from their work exposures, and at least thirteen died. Their teeth ached, became loose, and fell out. Their jaws decayed. Their long bones rotted, so they could not raise their arms or support themselves on their legs. They had anemia, rheumatic pains, and more.

The company had never warned the dial painters of the risks of radium exposure, and in fact heightened that exposure by instructing them to put the brushes in their mouths. Meanwhile, the company bosses and scientists kept their distance and protected themselves with lead shields. Some of the sick and dying workers sued US Radium—something that was virtually unprecedented at that time. The case was dismissed on a technicality by an unsympathetic court. Later, some of the workers obtained a paltry settlement of about $1,000 each.

Despite their dismal failure in court, the workers’ plight and their pioneering litigation effort roused press and public support. The shameful treatment of the Radium Girls, as they became known, helped raise public awareness of the need for laws protecting workers.

BACKGROUND

At first glance, you might not think of the Occupational Safety and Health Act1 as an environmental law. But on-the-job exposures to hazardous chemicals and physical agents are greater than for any other subset of the American population—in terms of frequency, dose, and potential for harm.

Occupational safety and health laws came first at the state level. In 1934 the federal Department of Labor established a Bureau of Labor Standards to help state governments develop and administer protective workplace standards. But states varied greatly in the extent to which their laws protected workers, and to which these laws were enforced. Workers continued to be killed and injured at an alarming rate.

To make matters worse, scientific studies were revealing that on-the-job exposure to hazardous substances was causing lung diseases, cancers, and other chronic diseases among workers—a problem presaged by the experience of the Radium Girls. There are many diseases from work exposures, and some do not show up for decades—for example, asbestos exposure causes both lung cancer and asbestosis, a crippling lung disease; byssinosis is a lung disease of textile workers caused by inhaling fibers; benzene exposure causes leukemia; and silicosis (black lung disease) affects miners.

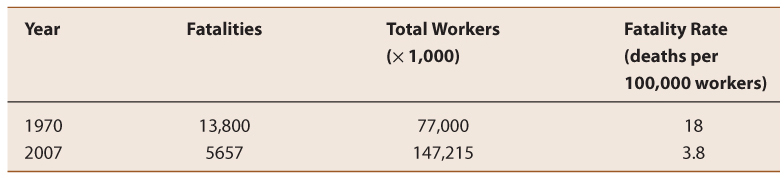

Congress enacted the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSH Act) in 1970, and the federal government assumed responsibility for regulating workplace safety. Although there is still much to be done, on-the-job safety has improved immensely since passage of the act. For example, fatalities dropped 59 percent from 1970 to 2007, even though the number of workers almost doubled (see table 10.1). (After 2007, the format for these statistics changed somewhat, but the comparable fatality rate in 2010 was 3.6.)

Table 10.1 Workplace Fatalities: A Comparison of 1970 versus 20072

Purpose of the Act

The stated purpose of the OSH Act is to assure, so far as possible, safe and healthful working conditions for every working man and woman in the United States.

Structure and Implementation

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), within the Department of Labor, is the federal agency chiefly responsible for implementing the OSH Act—specifically for the regulatory and enforcement functions. The scientific research function, however, is allocated to the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). NIOSH is a part of the Centers for Disease Control, which is a part the Department of Health and Human Services. By contrast, Congress structured the EPA to combine research and regulatory functions in the same agency.

The OSH Act permits and encourages states to participate in implementation. Twenty-five states have OSHA-approved state plans, authorizing them to implement the act.

Scope of the Act

The act covers all private sector employers and their employees. The act applies to employers as diverse as manufacturers, construction companies, agricultural concerns, law firms, hospitals, charities, and labor unions. Altogether, the act covers more than one hundred million employees in six million workplaces.

Who Is Not Regulated?

Although the act’s coverage is very broad, there are several noteworthy exemptions and limitations.3

- Small employers: There is an exemption—but only a partial exemption—for workplaces with up to ten employees. Even small employers are subject to certain protective provisions, including the worker right-to-know provisions discussed in this chapter (see Hazard Communication Standard).

- Government: Governments—federal, state, and political subdivisions of states—are not covered directly by the OSH Act. Instead, each federal department or agency has its own program covering its own employees. These programs must, however, be as protective as OSHA standards for private sector workers. Similarly, each state has its own program for state employees.

- Employers covered by other laws: Congress has established other laws and agencies that govern the activities of certain industries, including regulation of occupational safety and health. Examples are mining and railroads.

- Self-Employed: OSH Act protections do not cover a self-employed person. However, they do cover that person’s employees.

- Family farm: If a farm is worked only by immediate family members and has no other employees, it is not covered.

- Religious workers: The act does not cover employees of a religious organization, provided their work is religious. But the act does cover the organization’s secular employees.

- Domestic household employees.

Regulatory Approach

The basic approach of the OSH Act is to make employers responsible for worker safety. OSHA sets standards designed to make workplaces and working conditions safe. But there can never be a specific standard for every possible hazard, so there is a general default rule: employers are required affirmatively to ensure the safety of their own workplaces.

The OSH Act addresses both mechanical and chemical hazards. In keeping with the goals of this book, this chapter will focus on the latter. The act uses two main tools to protect against chemical hazards: exposure limits and information. Both will be discussed in the following sections.

WHAT ARE EMPLOYERS’ DUTIES?

The OSH Act imposes two duties on employers.5

Duty to Comply with Specific Standards

An employer must comply with all specific standards set by OSHA. There are many specific standards, aimed at a diverse array of hazards, including toxic substances, harmful physical agents (such as radiation), electrical hazards, fall hazards, hazardous waste, infectious disease, fire and explosion dangers, dangerous atmospheres, machine hazards, hazards associated with trenches and digging, and confined spaces.

General Duty to Provide a Safe Workplace

Every employer has a duty to maintain conditions and adopt practices reasonably necessary and appropriate to provide a safe workplace and protect workers on the job. This catch-all provision is very important. The number of potential workplace hazards is almost infinite. OSHA cannot realistically foresee and adopt specific standards for all of them. Recognizing this, the act requires employers to do more than comply with specific standards. Employers are responsible to find and correct hazards in their own workplaces.

HEALTH STANDARDS

Exposure to toxic and hazardous substances is one of the most serious threats facing American workers today. The most direct way OSHA seeks to protect workers from chemical hazards is by imposing standards6 called permissible exposure limits (PELs).

Permissible Exposure Limits (PEL)

A PEL establishes the maximum amount or concentration of a toxic or hazardous substance that workers can be exposed to. Each PEL is tailored to the individual substance—what hazards it poses and how. Most commonly, PELs apply to air exposure, although some PELs also set maximum limits of skin exposure. PELs commonly set limits averaged over an eight-hour shift. Some set limits for other time periods as well, such as short term (fifteen minutes) or a forty-hour workweek. To illustrate, the benzene standard provides:

Without this short-term exposure limit, it would be permissible to expose employees to as much as 32 ppm benzene for one 15-minute period each workday without violating the 8-hour TWA.

Monitoring and Other Requirements

Setting numeric limits is important, but how do you make sure they are met—that is, how do you give them teeth? In each standard, OSHA includes relevant requirements, which commonly include the following:

- Requirements—including methods—for monitoring and measuring of airborne levels.

- Medical surveillance of exposed workers, designed to detect signs of exposure. This typically consists of routine medical tests, such as blood counts or X-rays.

- Employee training and education, and the posting of warning signs, related to the hazards of the specific substance they are exposed to.

- Requiring that employers implement engineering and work practice controls as the preferred means of complying with PELs, to the maximum amount feasible. Respirators or other personal protective equipment (PPE) are acceptable only as a supplementary means of compliance, and only to the extent the employer can establish that full compliance with the preferred controls is not feasible.

- Although not the preferred means for PEL compliance, personal protective equipment is still important. If OSHA deems PPE essential, OSHA standards make the employer responsible to pay for it, and to ensure that employees have it and use it.