Negligence: Duty of Care

2

Negligence: duty of care

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

■ Understand the essential elements of a negligence claim

■ Understand the reasons for retreating from the Anns two-part test

■ Understand the role of policy in establishing the existence of a duty of care

■ Critically analyse the concept of duty of care

■ Apply the tests to factual situations to determine the existence of a duty of care

2.1 Duty of care

2.1.1 The origins of negligence and the neighbour principle

The historical background

The origins of negligence lie in other torts in a process known as an action on the case, a method of proving tort through showing negligence or carelessness. Traditionally most torts depended on proof of an intentional and direct interference with the claimant or with his property. Where this was impossible a claimant could make out a special case for liability based on careless deeds.

Long before the twentieth century judges had begun to recognise that many more people suffered loss or injury through careless acts than through intentional ones. Judges towards the end of the eighteenth century established the principle that defendants in certain specific situations might be considered liable for their careless act where they caused foreseeable loss or injury to a claimant. However, there was no general duty of care and there was no means of establishing one. One attempt to establish a formula through which duty situations could be identified came in Heaven v Pender [1883] 11 QBD 503.

In the case Brett MR suggested:

JUDGMENT

‘wherever one person is… placed in such a position with regard to another that everyone of ordinary sense… would at once recognise that if he did not use ordinary care and skill… he would cause danger or injury to the person or property of the other, a duty arises to use ordinary care and skill to avoid such danger.’

student mentor tip

‘Negligence is very important: Donoghue v Stephenson is a must to know!’ Audrie, University of Dundee

The development of a general test for establishing the existence of a duty of care

The modern tort of negligence begins with Lord Atkin’s groundbreaking judgment in Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562. A new approach was necessary in the case because no other action was available.

The judgment is important not just for the decision itself, or only for identifying negligence as a separate tort in its own right, but also for devising the appropriate tests for determining whether negligence has actually occurred.

CASE EXAMPLE

Donoghue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562

The claimant argued that she had suffered shock and gastroenteritis after drinking ginger beer from an opaque bottle out of which a decomposing snail had fallen when the dregs were poured A friend had bought her the drink and so the claimant was unable to sue in her own right in contract. She nevertheless claimed £500 from the manufacturer for his negligence and was successful. The House of Lords was prepared to accept that there could be liability on the manufacturer. Two major objections were discussed in the case. The first of these is referred to as the ‘contract fallacy’. A previous case, Winterbottom v Wright [1842] 10 M & W 109, appeared to contain a clear rule preventing a duty of care from being established in the absence of a contractual relationship. The parties to the action were the manufacturer of the ginger beer and the eventual consumer of his product, the ginger beer actually having been bought by the claimant’s friend from the owner of a roadside café. The judges rejected the application of this principle in the case. The second potential problem was one raised by Lord Buckminster, who objected to the possibility of a general test for establishing duty of care, and indeed to the specific duty established in the case. He did so on the basis that it would be destructive to commerce and would only harm consumers by the cost of paying damages in successful actions being added to the price of the manufacturer’s goods. Again the majority rejected this argument.

Lord Atkin’s judgment contained five critical elements:

■ Lack of privity of contract did not prevent the claimant from claiming.

■ Negligence was accepted as a separate tort in its own right.

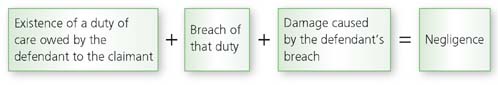

■ Negligence would be proved by satisfying a three-part test:

■ the existence of a duty of care owed to the claimant by the defendant;

■ a breach of that duty by falling below the appropriate standard of care;

■ damage caused by the defendant’s breach of duty that was not too remote a consequence of the breach.

■ The method of determining the existence of a duty of care is the so-called ‘neighbour principle’. This is not the ratio of the case but is rather obiter dicta. Nevertheless it is a vital guiding principle on which the actual ratio was ultimately dependent.

neighbor principle

A test used in negligence to establish whether a duty of care is owed

As Lord Atkin put it:

JUDGMENT

‘You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour. Who then in law is my neighbour?… persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in my contemplation as being affected so when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions in question.’

■ A manufacturer would owe a duty of care towards consumers or users of his/her products not to cause them harm. This is commonly referred to as the ‘narrow ratio’ of the case.

So from the ‘neighbour principle’ of Lord Atkin the tort of negligence is identified as being based on foreseeability of harm. The case gives us one clear example of a relationship where possible harm is foreseeable and a duty of care then exists – the duty of a manufacturer to the consumers or users of his or her products.

In one sense then the case of Donoghue v Stevenson gives us a very simple way of looking at negligence (see Figure 2.1).

It is important to note that there is a distinction between the duty of care in law (sometimes called the ‘notional duty’) and the duty of care in fact. In establishing duty the court must be certain that the case involves not just a risk of a type recognised by the law as leading to a duty but that the resulting risk is a type envisaged by the law. In Bourhill v Young [1943] AC 92 the court would not accept the existence of a duty in nervous shock because the claimant was not within the area of foreseeable harm. In doing so it approved the judgment of Cardozo J in the American case Palsgraf v Long Island Railway Co [1928] 284 NY 339. In imposing a duty then a judge must be certain not just that the circumstances are those where a duty is commonly accepted but that the particular defendant owes a duty in the circumstances to the particular claimant.

ACTIVITY

Quick quiz

In the following situation state which types of loss are recoverable from the manufacturer under the principle in Donoghue v Stevenson

Sacha bought a new toaster last week and on the second time of using the toaster it burst into fames. When she bought it the toaster was in a sealed package, and on both occasions that she has used it she has followed the manufacturer’s instructions precisely. Sacha is not in any way to blame for the damage that has resulted:

■ The toaster was completely destroyed and Sacha wants a replacement.

■ The decorating in the kitchen has suffered smoke damage and needs redecorating.

■ A cupboard behind the toaster was burnt so badly that it needs replacing.

■ Sacha’s arm was badly burnt as she tried to put out the fire and she would like compensation for the injury.

2.1.2. Development in defining duty and the two-part test in Anns

Over many years the tort of negligence developed incrementally, case by case, with a duty of care being established in numerous relationships. Lawyers were able to use the neighbour principle to argue for the extension of negligence into areas previously not covered by the tort where damage was a foreseeable consequence of the defendant’s acts or omissions.

At a much later stage in time the test was simplifed. The new test did not depend on a duty of care being determined in a given case according to how the case ftted in with past law. Under the new test a duty would be imposed because of the proximity of the relationship between the two parties unless there were policy reasons for not doing so. This of course means legal proximity (the extent to which the deeds of one can affect the other), not proximity based on physical closeness.

proximity

Refers to the fact that the defendant should contemplate that his actions may have an effect on potential claimants – rather than physical closeness

CASE EXAMPLE

Anns v Merton London Borough Council [1978] AC 728

The local authority had failed to ensure that building work complied with the plans, and as a result the building had inadequate foundations. The claimant, a tenant who had leased the property after it had changed hands many times, claimed that the damage to the property threatened health and safety and sued successfully. The decision was clearly arrived at on policy grounds.

Lord Wilberforce, in framing the ‘two-part’ test, suggested that the appropriate method of determining whether or not the defendant owed a duty of care in a given case was as follows.

■ First it should be established that there is sufficient proximity between defendant and claimant for damage to be a foreseeable possibility of any careless act or omission.

■ If this was established then it was only for the court to decide whether or not there were any policy considerations that might either limit the scope of the duty or remove it altogether.

Lord Wilberforce explained the position in the following terms:

JUDGMENT

‘the position has now been reached that in order to establish that a duty of care arises in a particular situation, it is not necessary to bring the facts of that situation within those of previous situations in which a duty of care has been held to exist. Rather the question has to be approached in two stages. First one has to ask whether, as between the alleged wrongdoer and the person who has suffered damage there is a sufficient relationship of proximity or neighbourhood such that, in the reasonable contemplation of the former, carelessness on his part may be likely to cause damage to the latter – in which case a prima facie duty of care arises. Secondly, if the first question is answered affrmatively, it is necessary to consider whether there are any considerations which ought to negative, or to reduce or limit the scope of the duty or the class of person to whom it is owed or the damages to which a breach of it may give rise.’

QUOTATION

‘The two part test looked deceptively simple. In effect the plaintiff, having established foresee-ability, raised a presumption of the existence of a duty which the defendant then had to rebut on policy grounds.’

J Murray, Street on Torts (11th edn, Butterworths, 2003)

The clear problem with the two-part test is the amount of discretion given to judges to determine whether or not a duty should exist in a given situation. As a result of a general unease with the test, the judgments in a series of cases in the 1980s display criticism by senior judges of the two-part test.

Lord Keith in Governors of the Peabody Donation Fund v Sir Lindsay Parkinson & Co Ltd [1985] AC 210 suggested that whether or not it was just and fair to impose a duty was a more appropriate test than mere policy considerations.

Lord Oliver in Leigh and Sillavan Ltd v Aliakmon Shipping Co Ltd (The Aliakmon) [1986] 1 AC 785 considered that the test should not be considered as giving the court a free hand to determine what limits to set in each case.

In Curran v Northern Ireland Co-ownership Housing Association Ltd [1987] AC 718 Lord Bridge indicated that the courts should be wary of extending those cases where a statutory body could be under a duty to control the activities of third parties. He also commented that the Anns test ‘obscured the important distinction between misfeasance and non-feasance’.

misfeasance

This is where the defendant has acted wrongly

In this last case Lord Bridge approved the judgment of Brennan J in the High Court of Australia in Sutherland Shire Council v Heyman [1985] 60 ALR 1. In this case the judge argued that it was ‘preferable that the law should develop novel categories of negligence incrementally and by analogy with established categories’.

In Yuen Kun Yeu v Attorney General of Hong Kong [1987] 2 All ER 705 Lord Keith also argued that the Anns test had been ‘elevated to a degree of importance greater than its merits’, and this he felt was probably not Lord Wilberforce’s original intention.

non-feasance

This is where the defendant has a duty to act and is liable for a failure to act

These judgments all show a much more cautious approach in determining the existence of a duty of care than need be the case under the two-part test. As a result of this the two-part test was in fact later discarded and the case of Anns also overruled.

CASE EXAMPLE

Murphy v Brentwood District Council [1990] 2 All ER 908

A house had been built on a concrete raft laid on a landfill site. The council had been asked to inspect and had approved the design of the raft. The raft was actually inadequate and cracks later appeared when the house subsided. The claimant sold the house for £35,000 less than its value in good condition would have been and sued the council for negligence in approving the raft. The House of Lords held that the council was not liable on the basis that the council could not owe a greater duty of care to the claimant than the builder. In doing so the court also overruled Anns and the two-part test, preferring instead a new three-part test suggested by Lords Keith, Oliver and Bridge in Caparo v Dickman [1990] 1 All ER 568.

2.1.3. The retreat from Anns and the three-part test from Caparo

In Caparo v Dickman the House of Lords had in fact shown some dissatisfaction with the two-part test and preferred a return to the more traditional incremental approach by reference to past cases. The test was able to change in Murphy because they had identified an incremental approach with three stages.

CASE EXAMPLE

Caparo v Dickman [1990] 1 All ER 568

Shareholders in a company bought more shares and then made a successful takeover bid for the company after studying the audited accounts prepared by the defendants. They later regretted the move and sued the auditors claiming that they had relied on accounts which had shown a sizeable surplus rather than the deficit that was in fact the case.

The House of Lords decided that the auditors owed no duty of care since company accounts are not prepared for the purposes of people taking over a company and cannot then be relied on by them for such purposes. The court also considered a three-stage test in imposing liability appropriate.

First, it should be considered whether the consequences of the defendant’s behaviour were reasonably foreseeable.

Second, the court should consider whether there is a sufficient relationship of proximity between the parties for a duty to be imposed.

Last, the court should ask the question whether or not it is fair, just and reasonable in all the circumstances to impose a duty of care.

In Caparo Lord Bridge explained the faws in the Anns two-part test, the need for the modern three-part test and also for a return to an incremental development in the law of negligence.

JUDGMENT

‘since the Anns case a series of decisions of the Privy Council and of your Lordship’s House have emphasised the inability of any single general principle to provide a practical test which can be applied to every situation to determine whether a duty of care is owed and, if so what is its scope. What emerges is that, in addition to the foreseeability of damage, necessary ingredients in any situation giving rise to a duty of care are that there should exist between the party owing the duty and the party to whom it is owed a relationship characterised by the law as one of “proximity” or “neighbourhood” and that the situation should be one in which the court considers it fair, just and reasonable that the law should impose a duty of a given scope upon the one party for the benefit of the other. We must now, I think, recognise the wisdom of the words of Brennan J in the High Court of Australia in Sutherland Shire Council v Heyman [1985] 60 ALR 1 where he said:

QUOTATION

‘It is preferable, in my view, that the law should develop novel categories of negligence incrementally and by analogy with established categories, rather than by a massive extension of a prima facie duty of care restrained only by indefinable “considerations which ought to negative or to reduce or limit the scope of the duty or the class of the person to whom it is owed”.’

Reasonable foresight

The basic requirement of foresight is simply that the defendant must have foreseen the risk of harm to the claimant at the time he or she is alleged to have been negligent.

This is slightly confusing given the fact that a claimant must then go on and satisfy the remoteness of damage test. It is also confusing because foreseeability of harm is also a necessary ingredient of proximity. However, although the two are quite closely linked they are still distinct concepts.

Foresight is always critical of course in determining whether or not there is a duty of care owed. It should also be remembered that there is no general, all embracing duty of care. The existence of the duty depends on the individual circumstances.

remoteness of damage

Also known as causation in law – refers to damage which is foreseeable and therefore which the courts are prepared to compensate – they would not compensate for damage that was too remote a consequence of the defendant’s breach

CASE EXAMPLE

Topp v London Country Bus (South West) Ltd [1993] 1 WLR 976

A bus company did not owe a duty of care when leaving a bus unattended and joy riders stole the bus and injured the claimant.

It is of course possible that attitudes to what is considered reasonably foreseeable can change, as can be seen from comparing the next two cases.

CASE EXAMPLE

Gunn v Wallsend Slipway & Engineering Co Ltd, The Times, 24 November 1989

There was held to be no duty of care to a woman who contracted mesothelioma from inhaling asbestos dust from her husband’s overalls. At the time the risk was felt to be unforeseeable.

But a contrary line has since been adopted. This will very often depend on the availability of technical information at a given point in time.

CASE EXAMPLE

Margereson v J W Roberts Ltd [1996] PIQR P358