Negligence

Negligence

2.1.1 Negligence – Origins and Character

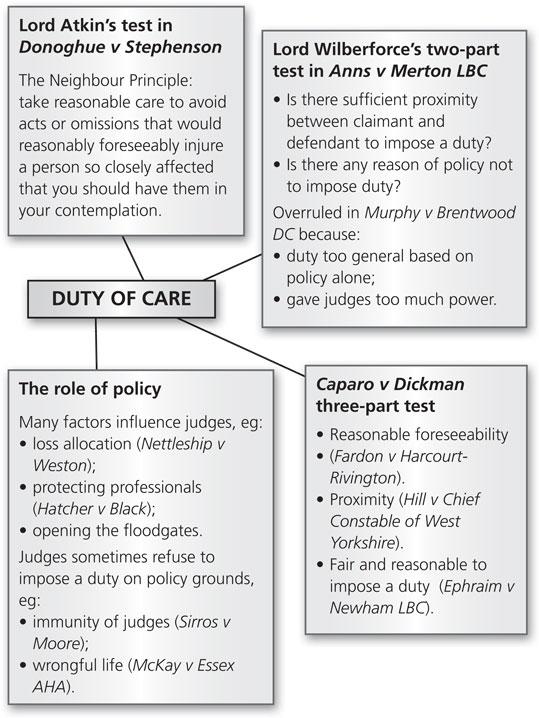

1. The modern starting point is Lord Atkin’s judgment in Donoghue v Stevenson (1932), which established negligence as a separate tort – though its origins were in actions on the case.

2. A new approach was needed, as no other action was available.

3. The judgment contained five key elements.

Negligence is a separate tort.

Negligence is a separate tort.

Lack of privity of contract is irrelevant to mounting an action.

Lack of privity of contract is irrelevant to mounting an action.

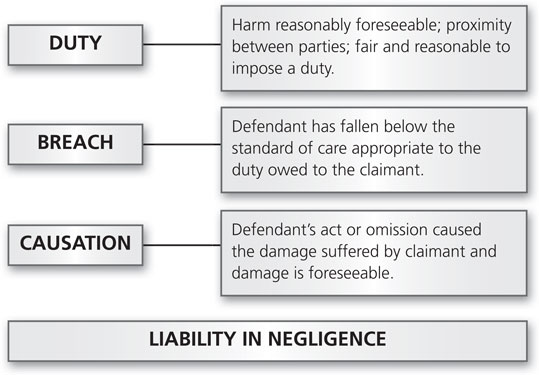

Negligence is proved as a result of satisfying a three-part test:

Negligence is proved as a result of satisfying a three-part test:

(i) there must be a duty of care owed by defendant to claimant;

(ii) the duty is breached by the defendant falling below the appropriate standard of care;

(iii) the defendant causes damage to the claimant that is not too remote a consequence of the breach.

Lord Atkin’s ‘Neighbour Principle’: ‘You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour. Who, then, in law, is my neighbour? Persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in my contemplation as being affected so when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions in question’.

Lord Atkin’s ‘Neighbour Principle’: ‘You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour. Who, then, in law, is my neighbour? Persons who are so closely and directly affected by my act that I ought reasonably to have them in my contemplation as being affected so when I am directing my mind to the acts or omissions in question’.

A manufacturer owes a duty to consumers and users of his products not to cause them harm.

A manufacturer owes a duty to consumers and users of his products not to cause them harm.

4. Thus broad principles were established to determine liability.

5. The law developed incrementally, establishing new duties.

6. Policy has always been a crucial element so the court will not only decide whether there is a duty, but whether there should be.

7. Many factors influence the judges:

loss allocation (Nettleship v Weston (1971));

loss allocation (Nettleship v Weston (1971));

moral considerations;

moral considerations;

practical considerations;

practical considerations;

protecting professionals (Hatcher v Black (1954));

protecting professionals (Hatcher v Black (1954));

constitutional obligations;

constitutional obligations;

the ‘floodgates’ argument;

the ‘floodgates’ argument;

the possible benefits of imposing duties (Smolden v Whitworth and Nolan (1997)).

the possible benefits of imposing duties (Smolden v Whitworth and Nolan (1997)).

8. Judges have often cited policy when refusing a duty of care:

liability of lawyers (Rondel v Worsley (1969)) – but now see Arthur J S Hall & Co v Simons & others (2000) and Moy v Pettman Smith and Perry (2005);

liability of lawyers (Rondel v Worsley (1969)) – but now see Arthur J S Hall & Co v Simons & others (2000) and Moy v Pettman Smith and Perry (2005);

liability of police (Hill v Chief Constable of West Yorkshire (1988)) so no duty to victims of crime or to witnesses (Brooks v Commissioner of Police (2005)) – but not where there is a positive duty to act (Reeves v Metropolitan Police Commissioner (1999)); nor where human rights are involved (Osman v UK (2000)) and breach of Article 6 ECHR; but no duty to protect a witness from attack and murder by a defendant in a criminal trial (Chief Constable of Hertfordshire v Van Colle; Smith v Chief Constable of Sussex (2008));

liability of police (Hill v Chief Constable of West Yorkshire (1988)) so no duty to victims of crime or to witnesses (Brooks v Commissioner of Police (2005)) – but not where there is a positive duty to act (Reeves v Metropolitan Police Commissioner (1999)); nor where human rights are involved (Osman v UK (2000)) and breach of Article 6 ECHR; but no duty to protect a witness from attack and murder by a defendant in a criminal trial (Chief Constable of Hertfordshire v Van Colle; Smith v Chief Constable of Sussex (2008));

immunity of judges (Sirros v Moore (1975));

immunity of judges (Sirros v Moore (1975));

alternative ways to compensate, e.g. CICB, MIB;

alternative ways to compensate, e.g. CICB, MIB;

rescues (Salmon v Seafarer Restaurants (1983));

rescues (Salmon v Seafarer Restaurants (1983));

specific claims (wrongful life) (McKay v Essex AHA (1982));

specific claims (wrongful life) (McKay v Essex AHA (1982));

where claimant belongs to an indeterminately large group (Monroe v London Fire and Civil Defence Authority (1991));

where claimant belongs to an indeterminately large group (Monroe v London Fire and Civil Defence Authority (1991));

where claimant is responsible for own misfortune (Governors of the Peabody Donation Fund v Parkinson (1984)).

where claimant is responsible for own misfortune (Governors of the Peabody Donation Fund v Parkinson (1984)).

9. At one point Lord Atkin’s test was simplified by Lord Wilberforce in Anns v Merton LBC (1978) into a two-part test.

a) Is there sufficient proximity between defendant and claimant to impose a prima facie duty?

b) If so, does the judge consider that there are any policy grounds which would prevent such a duty being imposed?

10. The Anns test was always seen as too broad because:

a) it creates a general duty based only on proximity;

b) it gives judges too much power to decide on policy alone.

11. A long line of cases expressed dissatisfaction with the Anns test, e.g. Governors of Peabody Donation Fund v Sir Lindsay Parkinson (1985); Caparo v Dickman (1990). The test was finally overruled in Murphy v Brentwood DC (1990).

12. It was replaced by a three-part test of Lords Oliver, Keith, Bridge in Caparo (1932).

a) Reasonable foresight (Fardon v Harcourt-Rivington and Topp v London Country Bus (South West) Ltd (1993)), but see also Margereson v J W Roberts Ltd, Hancock v JW Roberts Ltd (1996) compared to the earlier rule in Gunn v Wallsend Slipway & Engineering Co Ltd (1989).

b) Proximity (Hill (1988) and John Munroe v London Fire and Civil Defence Authority (1997)). See also the Court of Appeal in Sutradhar v Natural Environment Research Council (2004).

c) Is it fair and reasonable to impose duty? (Hemmens v Wilson Browne (1993)and Ephraim v Newham LBC (1993); and it is not fair, just and reasonable to impose a duty where it conflicts with a duty owed by the defendant to another party (Mitchell v Glasgow City Council (2009)).

13. Subsequent cases have approved this ‘incremental’ approach (Spring v Guardian Assurance (1995)); (Jones v Wright (1994)).

14. Policy has inevitably remained a major factor (Hill (1988)):

a) as with public, regulatory bodies; compare Philcox v Civil Aviation Authority (1995) and Perrett v Collins (1998) – but assumption of responsibility and special knowledge may create liability on public bodies (Thames Trains Limited v Health and Safety Executive (2002));

b) and immunity from suit for professionals (Kelley v Corston (1997) and Griffin v Kingsmill (1998));

c) and also for public services (Capital & Counties plc v Hampshire County Council (1997));

d) in Harris v Perry (2008) it was held that it was impractical for parents to keep children under constant supervision and it would not be in the public interest for the law to require them to do so.

15. The Anns test was flawed, but the new test is arguably no better:

it claims to follow the separation of powers theory;

it claims to follow the separation of powers theory;

but it is more complex and secret, and restricts development.

but it is more complex and secret, and restricts development.

2.1.2 The Duty of Care

1. Case law is crucial to identifying duty situations.

2. Negligence is not mere carelessness, so no duty no liability.

3. There must be a ‘duty on the facts’, not a mere notional duty.

4. The key questions are:

a) Is the situation or loss of a type to which negligence applies?

b) Does the defendant owe a duty to the actual claimant?

5. Numerous straightforward situations, e.g. employers/employees; fellow motorists; doctors/patients, manufacturers/consumers, etc.

6. However, courts have also considered many controversial situations.

2.2 Breach of the Duty of Care

2.2.1 The Standard of Care and Reasonable Man Test

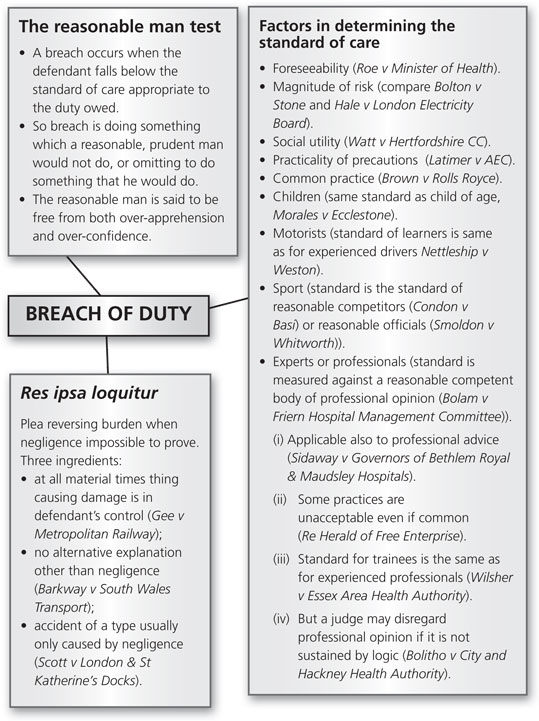

2. The standard is objectively measured by the ‘reasonable man’ test: ‘the omission to do something which a reasonable man would do, or doing something which a prudent and reasonable man would not do.’ Per Alderson B in Blyth v Birmingham Waterworks (1865).

3. The reasonable man has been described as ‘the “man on the street” or “the man on the Clapham omnibus” …’

4. Or, as MacMillan L.J. put it in Glasgow Corporation v Muir (1943), the test is ‘independent of the idiosyncrasies of the particular person whose conduct is in question … The reasonable man is presumed to be free from both over-apprehension and over-confidence’.

5. So breach of duty then is merely the same as fault.

6. Factors of policy and expediency are taken into account, e.g.:

who can best bear the loss;

who can best bear the loss;

whether or not the defendant is insured;

whether or not the defendant is insured;

how the decision might affect future behaviour;

how the decision might affect future behaviour;

the justice of the individual case;

the justice of the individual case;

how the decision affects society as a whole.

how the decision affects society as a whole.

7. Judges have established criteria by which to measure the standard.

2.2.2 Principles in Determining the Standard of Care

1. Foreseeability: no obligation for defendant to compensate for incidents beyond his normal contemplation or outside his existing knowledge; compare Roe v Minister of Health (1954) with Walker v Northumberland County Council (1995).

2. Magnitude of risk: the care expected depends on likelihood of risk – compare Bolton v Stone (1951) with Hale v London Electricity Board (1965).

3. Social utility: a risk averting a worse danger may be justified (Watts v Hertfordshire CC (1954)), but not any risk at all (Griffin v Mersey Regional Ambulance (1998)).

4. Practicality of precautions: need not take extraordinary steps or suffer extraordinary cost (Latimer v AEC (1953)) – but if defendant is in sufficient control to avoid harm then s(he) is obliged to act (Bradford- Smart v West Sussex County Council (2002) on preventing bullying in schools).

5. Common practice: usually, but not always, suggests non-negligent practice (Brown v Rolls Royce (1966)).

6. Specific classes of people have specific rules.

a) Children: originally not expected to take same care as adults (McHale v Watson (1966)), but see now Morales v Ecclestone (1991) and Armstrong v Cottrell (1993) and see Orchard v Lee (2009) for instance on boisterous activity in a playground’.

b) The disabled and sick: standard appropriate to disability.

c) Motorists: the same standard applies to all drivers, even learners (Nettleship v Weston (1971)) and one becoming ill while driving (Roberts v Ramsbottom (1980)), but not if unaware of the illness (Mansfield v Weetabix Ltd (1997)).

d) People lacking specialist skills: not expected to show same standard as a skilled person (Phillips v Whiteley Ltd (1938)).

e) Sport: standards applicable to reasonable competitors (Condon v Basi (1985)), reasonable officials (Smoldon v Whitworth (1997)) or reasonable sporting authority (Watson v British Boxing Board of Control (2001)). But standard depends on individual circumstances (Pitcher v Huddersfield Town FC (2001)) and ‘horseplay’ may be covered by the same standard as sport (but only where the defendant’s conduct amounts to a high degree of carelessness (Blake v Galloway (2004)).

7. Experts and professionals are not bound by the standards of a reasonable man but those of a reasonable practitioner of that particular skill or profession (Bolam v Friern Hospital Management Committee (1957)).

a) The test also applies to advice and information (Sidaway v Governors ofBethlem Royal & Maudsley Hospitals (1985)) and warning of risk (Chester v Afshar (2002)).

b) And to diagnosis (Ryan v East London & City Health Authority (2001)).

c) So professionals need only provide expert witnesses who agree with conduct in question (Whitehouse v Jordan (1981)).

d) Some practices are unacceptable even though common (Re Herald of Free Enterprise (1989)).

e) Trainees must show the same degree of skill as experienced professionals (Wilsher v Essex AHA (1988)).

g) The rule has been approved since. ‘There is seldom any one answer exclusive of all others to problems of professional judgement.

A court may prefer one body of opinion to the other; but that is no basis for a conclusion of negligence …’ Per Lord Scarman in Maynard v West Midlands RHA (1985).

h) Only a small number of doctors following the practice is sufficient to relieve liability (De Freitas v O’Brien and Conolly (1995), where 11 out of 1000 would have operated).

i) However, the test has been subject to many criticisms:

it overprotects professionals;

it overprotects professionals;

it allows the professionals to set the standard;

it allows the professionals to set the standard;

it is inconsistent with negligence principles generally;

it is inconsistent with negligence principles generally;

it can often legitimize quite marginal practices;

it can often legitimize quite marginal practices;

definition of a competent body of opinion is too imprecise;

definition of a competent body of opinion is too imprecise;

the test can lead to professionals closing ranks.

the test can lead to professionals closing ranks.

j) Numerous recent cases have challenged its authority:

Newell v Goldberg (1995);

Newell v Goldberg (1995);

Lybert v Warrington HA (1996);

Lybert v Warrington HA (1996);

Thompson v James and Others (1996) – failure by GP to follow guidelines in warnings about measles vaccinations, and claimant brain damaged as a result.

Thompson v James and Others (1996) – failure by GP to follow guidelines in warnings about measles vaccinations, and claimant brain damaged as a result.

k) If the judge feels that the opinion held is not sustained by logic, then it may be disregarded (Bolitho v City and Hackney Health Authority (1997)).

2.2.3 Proof of Negligence and Res Ipsa Loquitur