Mistake

9

Mistake

Contents

9.4 Mistakes nullifying agreement (‘common mistake’)

9.5 Mistakes negativing agreement

9.8 Contracts signed under a mistake

This chapter deals with situations where a contract is affected by a mistake on the part of one or both parties. The general approach of the English courts and the different categories of mistake are dealt with first. The main topics then discussed are:

Mistakes nullifying agreement. This deals with mistakes where the parties have reached agreement, but on the basis of an important mistake – such as the existence of the subject matter.

Mistakes nullifying agreement. This deals with mistakes where the parties have reached agreement, but on the basis of an important mistake – such as the existence of the subject matter.

Performance must be impossible or radically different from that which the parties had agreed.

Performance must be impossible or radically different from that which the parties had agreed.

But mistakes as to quality will not generally render the contract void.

But mistakes as to quality will not generally render the contract void.

Mistakes negativing agreement. This type of mistake means that the parties were never in agreement. This may be because:

Mistakes negativing agreement. This type of mistake means that the parties were never in agreement. This may be because:

they were at cross-purposes (‘mutual mistake’);

they were at cross-purposes (‘mutual mistake’);

one party was aware of the other’s mistake (‘unilateral mistake’).

one party was aware of the other’s mistake (‘unilateral mistake’).

Mistake as to the identity of the other party. This is generally a type of unilateral mistake. It will only render the contract void where the identity was of vital importance to the other party. It is easier to establish an operative mistake of identity in contracts made at a distance (for example, by post) as opposed to those made face to face.

Mistake as to the identity of the other party. This is generally a type of unilateral mistake. It will only render the contract void where the identity was of vital importance to the other party. It is easier to establish an operative mistake of identity in contracts made at a distance (for example, by post) as opposed to those made face to face.

Mistake is a common law concept. In some circumstances the application of equitable principles may lead to:

Mistake is a common law concept. In some circumstances the application of equitable principles may lead to:

the refusal of specific performance;

the refusal of specific performance;

rectification of a written contract.

rectification of a written contract.

Non est factum. This is a plea that a person signed a document under a misapprehension as to its effect. It will only be effective where the mistake related to the nature of the document, and the person signing it had not acted carelessly.

Non est factum. This is a plea that a person signed a document under a misapprehension as to its effect. It will only be effective where the mistake related to the nature of the document, and the person signing it had not acted carelessly.

This chapter is concerned with the situations in which a contract may be regarded as never having come into existence, or may be brought to an end, as a result of a mistake by either or both of the parties. Although the overall theme is that of ‘mistake’, as will be seen, the situations which fall within this traditional categorisation are varied, and do not have any necessary conceptual unity. Moreover, they may have a considerable overlap or interaction with other areas of contract law – in particular, offer and acceptance, misrepresentation and frustration.2

The rules developed by the courts impose fairly heavy burdens on those arguing that a mistake has been made. This is not surprising. It would not be satisfactory if a party to a contract could simply, by saying ‘I’m sorry, I made a mistake’, unstitch a complex agreement without any thought for the consequences for the other party, or any third parties who might be involved. To allow this to be done would be to strike at the purposes of the law of contract, which has as one of its main functions the provision of a structure within which people can organise their commercial relationships with a high degree of certainty. On the other hand, a fundamental principle of the English law of contract is that, as far as possible, the courts should give effect to the intentions of the parties. If either, or both, of the parties has genuinely made a mistake as to the nature of their contract, to enforce it may run counter to their intentions.3 The courts do, therefore, recognise the possibility of mistakes affecting, or even destroying, contractual obligations that would otherwise arise. The power to intervene in this way is, however, used with considerable circumspection.

This general reluctance to allow mistakes to affect a contract does not, of course, prevent the parties themselves from agreeing that a mistake will allow the party who has made the mistake to rescind the contract. This is not unusual in relation to consumer contracts made with large chain stores. These organisations often feel able (presumably because of their volume of business and their strength of position in the market) to allow customers who have simply changed their minds to exchange or return goods even though they are in no way defective. As was noted in Chapter 2, there are also some statutory provisions which allow consumers a short period in which to change their minds about particular sorts of contract, particularly those involving ‘distance contracts’ or long-term credit arrangements.4 In such a situation, the consumer who realises that he or she has made a mistake of some kind in relation to the contract will be able to escape from it, provided that action is taken within the specified time limits. These arrangements are, however, exceptions to the general position under the common law, which will only allow a party to undo the agreement in a limited range of circumstances.

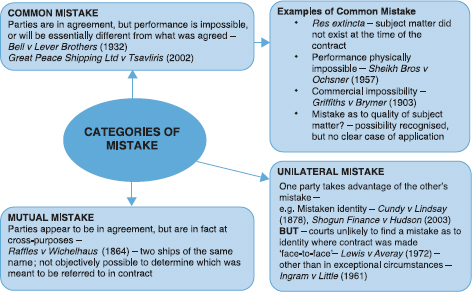

As noted above, there are various ways in which a party may make a mistake in relation to the contract. It may, for example, relate to the subject matter, the identity of the other contracting party or the specific terms of the contract. Three particular types of mistake may be identified. In the first, the parties are found to have reached agreement, but on the basis of an assumption as to the surrounding facts which turns out to be false (for example, the subject matter of the contract has at the time of the agreement ceased to exist). The mistake may, following the House of Lords’ decision in Kleinwort Benson Ltd v Lincoln City Council,5 be one of law. This was confirmed by the Court of Appeal in Brennan v Bolt Burdon.6 In this case a dispute had been settled on the basis of a ruling in a first instance decision that was then overturned on appeal. The claimant sought to set aside the settlement on the basis that it was based on a mistake of law. This argument succeeded in the High Court. The Court of Appeal set out the relevant approach in these terms:7

(1) As with any other contracts, compromises or consent orders may be vitiated by a common mistake of law. (2) It is initially a question of construction as to whether the alleged mistake has that consequence. (3) Whilst a general release executed in a prospective or nascent dispute requires clear language to justify an inference of an intention to surrender rights of which the releasor was unaware and could not have been aware …, different considerations arise in relation to the compromise of litigation which the parties have agreed to settle on a give-and-take basis … (4) For a common mistake of fact or law to vitiate a contract of any kind, it must render the performance of the contract impossible …

The question was, therefore, whether the courts below were correct to find that in this case there was a sufficient mistake of law to vitiate the agreement. The Court of Appeal found that there was not. A distinction can be drawn between situations where there is an unequivocal but mistaken view of the law, and where there is a doubt as to the law. The majority of the Court of Appeal felt that this case involved a doubt as to the law of service at the time the compromise agreement was made, rather than an unequivocal mistake. Moreover, the compromise agreement remained possible to perform. As a result, the appeal was allowed and the claimant was held to her compromise agreement.

Figure 9.1

This type of mistake, whether of fact or law, is the type of mistake referred to by Lord Atkin in Bell v Lever Bros8 as a mistake which ‘nullifies’ consent.9 There is here, in technical terms, a valid contract (in that it is formed by a matching offer and acceptance and supported by consideration) but it would, if put into effect, operate in a way which is fundamentally different from the parties’ expectations.10 The courts will therefore sometimes intervene to set the contract aside, and treat it as if it had never existed. This type of mistake has close links with the doctrine of ‘frustration’, which applies in situations where events after the formation of the contract (such as the destruction of the subject matter) fundamentally affect the nature of the agreement.11

The second and third types of mistake arise where the court finds that there is, in fact, a disagreement between the parties as to some important element of the contract. These are mistakes that Lord Atkin, in Bell v Lever Bros, referred to as ‘negativing consent’, in that they are said to operate to prevent a contract ever existing, because of the lack of agreement between the parties. Within this general category, however, two different situations must be distinguished. First, it may be that neither party is aware of the fact that the other is contracting on the basis of different assumptions as to the nature or terms of the agreement. They are at cross-purposes, but do not realise this until after the contract has apparently been agreed.12 This situation relates to the issues discussed in Chapter 2, in that it can be questioned whether there was ever a matching offer and acceptance. The second type of situation where there may be a mistake ‘negativing’ agreement is where one party is aware of the mistake being made by the other, and indeed may even have encouraged it.13 Where such encouragement has taken place there is likely to be an overlap with misrepresentation; dissolution of the contract on the basis of mistake is then only likely to be sought where the remedies for misrepresentation would be inadequate.14

Although, as has been noted above, there is a lack of conceptual unity in this area, the theme which may be said to link these various situations is that of ‘agreement failure’. There is an apparent agreement between the parties, but that agreement is either impossible to perform, or if performed would operate in a way which would be contrary to the expectations of at least one of the parties. Because this is the focus, there is little scope here for reliance-based remedies. If a mistake is operative,15 then the primary remedy will be to set the agreement aside, either in its entirety16 or on particular terms.17 Damages are not awarded in relation to a contract which has been based on an operative mistake.18

The clearest type of mistake which renders a contract fundamentally different from that which the parties thought they were agreeing to, and which will be regarded as rendering the contract void, is where the parties have made a contract about something which has ceased to exist at the time the contract is made.20 If, for example, the contract concerns the hire of a specific boat which, unknown to either party, has been destroyed by fire the day before the contract was made, the agreement will undoubtedly be void for common mistake. The parties have reached agreement, but that agreement is nullified by the fact that the subject matter no longer existed at the time of the agreement. This type of common mistake is sometimes referred to by the Latin tag of res extincta. An example from the cases is Galloway v Galloway.21 The parties, who thought they had been married to each other, made a separation agreement. It was then discovered that their supposed marriage was invalid because the husband’s previous wife was still alive. As a result, the separation agreement was void and the ‘husband’ had no liability under it.

Where there is a contract for the sale of specific goods, and the goods without the knowledge of the seller have perished at the time when the contract is made, the contract is void.

The word ‘perished’ almost certainly encompasses more than simply physical destruction, as is shown by the pre-SGA 1893 case of Couturier v Hastie.22 The contract in this case was for the purchase of a cargo of corn. At the time of the contract, the cargo had, because it was starting to deteriorate, been unloaded and sold to someone else. The purchaser was held to have no liability to pay the price. There are some doubts, however, as to the true basis for the decision in this case; these are referred to in 9.4.2.23

9.4.1 SUBJECT MATTER THAT NEVER EXISTED

The cases we have been considering deal with the situation where the subject matter did exist at one point, but has ceased to do so by the time of the contract. The position is more difficult where the subject matter has never existed. There seems no logical reason why the contract should not equally be void for mistake in such a case, but this was not the view of the High Court of Australia in McRae v Commonwealth Disposals Commission.24 The Commission had invited tenders for a salvage operation in relation to an oil tanker, said to be ‘lying on the Jourmand Reef’. The plaintiffs were awarded the contract, but on arrival found that neither the tanker nor the reef existed. The Commission claimed that the contract was void for mistake, and that they therefore had no liability. The court held, however, that there was a contract, in that the Commission had to be taken to have warranted the existence of the tanker. The plaintiffs were entitled to damages to compensate for their costs in putting together the abortive enterprise.

9.4.2 IN FOCUS: THE TRUE BASIS FOR THE DECISION IN COUTURIER v HASTIE

In reaching its conclusion in McRae, the court did not accept that the decision in Couturier v Hastie was truly based on ‘mistake’. It was simply that the plaintiff’s claim in that case, that the price was payable on production of the shipping documents, could not be upheld as being part of the contract. It is certainly true that the House of Lords in Couturier v Hastie never mentioned mistake as the basis for its decision. The case is perhaps in the end best regarded as an example of the kind of situation in which an operative mistake could occur, and which would now fall within s 6 of the SGA 1979, rather than as a direct authority on the issue.

For Thought

What do you think the outcome of McRae would have been if there had been a ship in the specified location, but it had already been salvaged by the time the Commission made the contract with McRae?

9.4.3 HAS THERE BEEN A PROMISE THAT THE SUBJECT MATTER EXISTS?

McRae can be taken to indicate a more general principle to the effect that where one of the parties has specifically promised that the subject matter exists, then mistake has no role to play, and the other party can sue for breach of the promise. This could apply not only where the subject matter has never existed, but also where it did once exist and has been destroyed prior to the agreement. This makes particular sense where, as in McRae, one party can reasonably be taken to have superior knowledge about the existence of the subject matter. The other party is then relying on this superior knowledge in entering into the contract, and it may well be appropriate that if that reliance turns out to be unjustified, damages should be recoverable. Simply setting the agreement aside because it has failed might not be sufficient in such circumstances.

There would be a difficulty, however, in applying this to contracts for the sale of goods. This is because s 6 of the SGA 1979 states that, in such a case, the contract is void. There is no provision in the section for the parties to agree to the contrary, and it is by no means clear that the courts would imply one.25 There is no problem where the goods never existed, because the use of the word ‘perished’ in s 6 implies that the goods did once exist: if they did not, then the section has no application. It would be odd, however, if the law drew such a clear distinction, simply in sale of goods cases, between the situation where the subject matter once existed and the situation where it never existed. There are several ways in which such an odd result might be avoided. First, it might be said that the McRae approach only applies where the subject matter never existed. This would produce a workable rule, but it would be difficult to see any policy behind the distinction. Second, it might be argued that the word ‘perished’ in s 6 encompasses the situation where the goods never existed. This interpretation would lead to all sale of goods contracts being treated in the same way, but differently from other contracts. However, it is again difficult to see any underlying policy that would justify the distinction. Third, it could be argued, as suggested by Atiyah,26 that the courts should be prepared to interpret s 6 as not intended to apply whenever specific promises about the existence of the goods have been made. This would produce the most analytically satisfactory answer in that it would align all sale of goods contracts with the general rule. It probably also involves, however, the most adventurous statutory interpretation, and it is by no means certain that the courts would be willing to adopt it. The area therefore remains unclear. The approach adopted in McRae, however, seems sensible, and is in line with the modern law’s recognition that disappointed reliance should generally be compensated. It makes sense for that approach to be adopted wherever possible, even if it does leave contracts for the sale of specific goods that have perished in an anomalous position.

9.4.4 IMPOSSIBILITY OF PERFORMANCE

An operative common mistake may also arise where, although the subject matter of the contract has not been destroyed, performance is, and always was, impossible. This may result from a physical impossibility, as in Sheikh Bros v Ochsner,27 where land was not capable of growing the quantity of crop contracted for, or legal impossibility,28 where the contract is to buy property which the purchaser already owned.29 A contract based on a mistake of law will also fall into this category.30 There is also one case, Griffith v Brymer,31 where a contract was found void for what may be regarded as ‘commercial impossibility’.32 The contract was to hire a room to view an event which, at the time of the contract, had already been cancelled. Performance of the contract was physically and legally possible, but would have had no point.33

9.4.5 MISTAKE AS TO QUALITY

Can there be an operative common mistake where the parties are mistaken as to the quality of what they have contracted about? Suppose A sells B a table, both parties being under the impression that they are dealing with a valuable antique, whereas it subsequently turns out to be a fake? Can B claim that the contract should be treated as void on the basis of a common mistake?34 The leading House of Lords authority is Bell v Lever Bros.35

Key Case Bell v Lever Bros (1932)

Facts: The plaintiffs (Lever Bros) had reached an agreement for compensation with the defendant over the early termination of his contract of employment. This termination agreement was itself a contract, providing for the payment of £50,000. The plaintiffs then discovered that the defendant had previously behaved in a way (entering into secret deals for his personal benefit) that would have justified termination without compensation. They therefore argued that the compensation contract should be regarded as being void for mistake. At trial, although the jury found that the defendant had not been fraudulent, the judge held that the compensation agreement was void for mistake. The case was appealed to the House of Lords.

Held: The House of Lords was reluctant to allow a mistake as to the quality, or value, of what had been contracted for to be regarded as an operative mistake. As Lord Atkin put it:36

In such a case, a mistake will not affect assent unless it is the mistake of both parties and is as to the existence of some quality which makes the thing without the quality essentially different from the thing as it was believed to be.

This would not be the case in an example such as that of an antique that turns out to be a fake. Lord Atkin again comments:37

Applying this approach to the case before the House, the conclusion was that there was no operative mistake. The plaintiffs had obtained exactly what they had bargained for, that is, the release of the contract with the defendant. The fact that the plaintiffs could have achieved the same result without paying compensation by relying on the defendant’s earlier conduct was immaterial.

This conclusion has sometimes been regarded as indicating that there can never be an operative mistake as to quality.38 However, the decision does not go quite that far, as the first quotation from Lord Atkin above shows. He specifically recognises the possibility that a mistake as to whether the subject matter of the contract has a particular quality may nullify consent provided it is a quality, the absence of which makes the subject matter ‘essentially different’. The difficulty is that if, as was held in Bell v Lever Bros, a mistake worth £50,000 does not make a contract essentially different, then what kind of mistake will do so? The fact that Bell did not shut the door on operative mistakes as to quality was, however, noted by Steyn J in Associated Japanese Bank Ltd v Credit du Nord SA.39 He held that a contract of guarantee, which was given on the basis of the existence of certain packaging machines, was void at common law when it turned out the machines did not exist at all. B, as a means of raising capital, had entered into an arrangement with the plaintiff bank, under which the bank bought the four machines from B for £1,021,000. The bank then immediately leased the machines back to B. B, of course, had obligations to make payments under this lease to the plaintiff. These obligations were guaranteed by the defendant bank. B was unable to keep up the payments, and the plaintiff sought to enforce the guarantee against the defendant, by which time it had been discovered that the machines had never existed. This mistake, which had been made by both plaintiff and defendant, of course, had great significance for the guarantee. There is no doubt that the defendant would not have given the guarantee if it had known the truth. But was the guarantee rendered void by this mistake? Steyn J refused to accept that Bell precluded an argument based on common mistake as to quality. His view was that, on the facts, such a mistake was not operative in Bell, not least because it was by no means clear that Lever Bros would have acted any differently even if they had known the truth. It was open, therefore, to consider whether the mistake was operative in the case before him. It should be noted that this was not a case of res extincta, though it comes close. The machines were not the subject matter of the contract under consideration. The subject matter was in fact a contract in relation to the machines the performance of which had been supported by a guarantee given by the defendant. Steyn J concluded:40

For both parties, the guarantee of obligations under a lease with non-existent machines was essentially different from a guarantee of a lease with four machines which both parties at the time of the contract believed to exist.

The contract of guarantee was therefore void for common mistake at common law.41 The position would therefore seem to be that some mistakes as to the quality, or value, of the subject matter of the contract can give rise to an operative mistake provided that the mistake has a sufficiently serious effect in relation to matters which are fundamental to the contract. There are obiter statements in Nicholson and Venn v Smith-Marriott,42 where the mistake was as to the provenance of antique table linen, which would also support such a view, though equally, in Leaf v International Galleries,43 where the mistake was as to whether a picture was painted by Constable, there are obiter statements which envisage a very limited role for this type of mistake. The fact that there are so few reported cases where it has been held that a common mistake is operative to avoid the contract at common law suggests that the latter view may well be correct.

This view is reinforced by the most recent reconsideration of the area by the Court of Appeal in Great Peace Shipping Ltd v Tsavliris (‘The Great Peace’).44

Key Case Great Peace Shipping Ltd v Tsavliris (‘The Great Peace’) (2002)

Facts: The contract concerned the charter of a ship, The Great Peace, to provide urgent assistance with a salvage operation. At the time of the contract both parties thought that the ship was about 35 miles from the salvage site. In fact it was about 410 miles away. When the charterer discovered this, it found another ship that was much closer and sought to avoid the contract for The Great Peace on the basis of common mistake.

Held: The Court of Appeal held that the mistake was not sufficiently serious to render the contract void at common law – it would still have been possible for The Great Peace to render assistance at the salvage, even though at a later time than anticipated. The principles set out in Bell v Lever Bros were confirmed as indicating the correct approach to such issues. In coming to this conclusion, the Court of Appeal took the opportunity to review the whole basis for the doctrine of common mistake. It came to the view that it was properly regarded as being based not on any theory of terms to be implied into the contract, but as a rule of law similar to that which operates in relation to the doctrine of frustration.45 The court restated the requirements for common mistake in the following way (which it saw as consistent with Bell v Lever Bros):46

| (i) | there must be a common assumption as to the existence of a state of affairs; |

| (ii) | there must be no warranty by either party that that state of affairs exists; |

| (iii) | the non-existence of the state of affairs must not be attributable to the fault of either party; |

| (iv) | the non-existence of the state of affairs must render performance of the contract impossible; |

| (v) | the state of affairs may be the existence, or a vital attribute, of the consideration to be provided or the circumstance which must subsist if performance of the contractual adventure is to be possible. |

Applying these principles to the facts of the case, there was no operative common mistake.

Point (ii) (and to some extent (iii)) of this analysis obviously deals with the situation that arose in McRae v Commonwealth Disposals Commission.47 The reference to ‘impossibility’ in point (iv) must be read in the light of the analogies which the court was drawing with the doctrine of frustration. Under that doctrine, a contract may be discharged if performance has become impossible or ‘radically different’ from that which the parties intended. It would seem that such an approach should also apply in relation to mistake. That this is the view of the Court of Appeal in The Great Peace is confirmed by its treatment of mistakes as to quality. As will be seen, in point (v) it refers to a ‘vital attribute’ which may not have existence, and this clearly extends the scope of the doctrine beyond physical non-existence of the subject matter. Moreover, the court approved the analysis of Steyn J in the Associated Japanese Bank case, in which he concluded that Bell v Lever Bros still left open the possibility of a mistake as to quality rendering a contract void where the mistake renders ‘the subject matter of the contract essentially and radically different from the subject matter which the parties believed to exist’.48 The Court of Appeal’s specific approval of this passage, and of the conclusions reached by Steyn J on the facts of the Associated Japanese Bank case, confirm that mistakes as to quality may render a contract void, albeit very rarely.

On the facts which arose in The Great Peace, the Court of Appeal agreed with the trial judge that the mistake as to the position of the vessel was not sufficiently serious to render the contract void. In particular, when the true position of the vessel was discovered, the charterers did not cancel the contract until they had located another vessel that was nearer. The implication was that if no other such vessel had been located, they would have continued with the charter concerning The Great Peace. If that was the case, it could not be argued that the contract for The Great Peace was ‘impossible’ or even ‘radically different’ from that which the parties had intended.

9.4.6 EFFECT OF AN OPERATIVE COMMON MISTAKE

The effect of an operative common mistake at common law is to render the contract void ab initio (from the beginning). It is as if the contract had never existed, and therefore, as far as is possible, all concerned must be returned to the position they were in before the contract was made. This applies equally to third parties, so that the innocent purchaser of goods which have been ‘sold’ under a void contract will be required to disgorge them, and hand them back to the original owner. These powerful and far-reaching consequences perhaps explain why the courts have shown a reluctance to extend the scope of common mistake too far, preferring to allow the flexible application of equitable remedies to pick up the pieces in many cases. The use of equity has, however, been significantly reduced since the Court of Appeal’s decision in The Great Peace.49

As indicated above, there are two categories of mistake that may have the effect of negativing agreement – that is, where the contract fails because there never was an agreement between the parties as to some essential matter. The first category is where neither side is aware of the fact that the other is contracting on a different basis. The lack of agreement is ‘mutual’. The second category is where one party is aware of the other’s mistake. Here the mistake is ‘unilateral’. These two categories will be considered separately.

9.5.1 ‘MUTUAL MISTAKE’

A classic example of a situation that might give rise to this kind of mistake is to be found in Raffles v Wichelhaus.50

Key Case Raffles v Wichelhaus (1864)

Facts: The alleged contract was for the purchase of a cargo of cotton due to arrive in England on the ship Peerless, from Bombay. There were two ships of this name carrying cotton from Bombay, one of which left in October, the other in December.

Held: The plaintiff offered the December cargo for delivery, but the defendant refused to accept this, claiming that he intended to buy the October cargo. The plaintiff tried to argue that the contract was simply for a certain quantity of cotton, and that the ship from which it was to be supplied was immaterial. The defendant, however, put his case in these terms:51

There is nothing on the face of the contract to shew that any particular ship called the Peerless was meant; but the moment it appears that two ships called the Peerless were about to sail from Bombay there is a latent ambiguity, and parol evidence may be given for the purpose of shewing that the defendant meant one Peerless, and the plaintiff another. That being so, there was no consensus ad idem, and therefore no binding contract.

The court stopped argument at this point, and held for the defendant.

There is, however, no report of any judgment in Raffles v Wichelhaus, so it is impossible to be certain of the exact basis of the decision. It is perhaps significant, however, that a few years later the case was cited by Hannen J in Smith v Hughes as authority for the proposition that:52

… if two persons enter into an apparent contract concerning a particular person or ship, and it turns out that each of them, misled by a similarity of name, had a different ship or person in his mind, no contract would exist between them.

Whatever the precise basis for the decision in Raffles v Wichelhaus itself, therefore, there seems no doubt that if the parties are at cross-purposes, the contract will be void for mutual mistake. This will, of course, only apply where there is a fundamental ambiguity in the contract, and no objective means of resolving it.

This type of mistake raises a question which was discussed in Chapter 2 – that is, how do the courts decide what the parties intended? Clearly the intentions can only be inferred from the words and actions of the parties, rather than their actual states of mind. The approach is therefore primarily objective – what would a reasonable person viewing the actions and hearing the statements of the parties think that they intended? If, taking the objective view, there was agreement, then the contract will not be avoided for mutual mistake. As was noted in Chapter 2,53 however, the objective valuation may be made from the point of view of one of the parties,54 or from the point of view of an independent third party.55 It seems that in the area of mutual mistake, the question of whether there is an agreement based on detached objectivity is going to be the crucial question. The facts of a mutual mistake case will often be such that both parties may be able to argue that they reasonably believed the other party to be intending on a particular basis. The outcome of the case would then depend on who was bringing the action. That was clearly not the approach taken in Raffles v Wichelhaus.56 The plaintiffs there could have argued that they intended to sell the December cargo and reasonably believed that that was what they believed the defendants were intending to buy. Equally, the defendants could argue that they reasonably believed that the plaintiffs were intending to sell the October cargo. If the defendants’ view had prevailed, it would have meant that there was a contract for sale of the October cargo, and the plaintiff was in breach of contract. This was not the outcome of the case, however.57 It appears to have been the view of the court that there was no contract at all.

This will not necessarily be the outcome, however, if, from a point of view of detached objectivity, a third party would reasonably believe that the contract had been made on particular terms. Thus, in Rose (Frederick E) (London) Ltd v William H Pim Jnr & Co Ltd,58 there was confusion between the parties as to whether they were contracting about ‘horsebeans’ or ‘feveroles’ (a particular type of horsebean). From the point of view of detached objectivity, however, the contract simply appeared to be for ‘horsebeans’, and that was how it was interpreted by the court.59