Misrepresentation

8

Misrepresentation

Contents

8.3 Definition of misrepresentation

8.4 Remedies for misrepresentation

8.5 Exclusion of liability for misrepresentation

The concept of misrepresentation is concerned with pre-contractual statements, which induce a contract, but turn out to be false. There are other remedies for some false statements of this kind, such as collateral contracts, but a claimant will often wish to rely on the remedies for misrepresentation. The following issues are important in deciding if a remedy is available on this basis:

Definition. A misrepresentation must be

Definition. A misrepresentation must be

made by one party to the other;

made by one party to the other;

a statement of existing fact or law;

a statement of existing fact or law;

generally in the form of a positive statement, rather than silence. There are, however, a number of exceptions to this principle – for example, when circumstances change between the making of the statement and the making of the contract;

generally in the form of a positive statement, rather than silence. There are, however, a number of exceptions to this principle – for example, when circumstances change between the making of the statement and the making of the contract;

something which in part, at least, induces the other party to make the contract.

something which in part, at least, induces the other party to make the contract.

Remedies for misrepresentation

Remedies for misrepresentation

Rescission of the contract. This is the main remedy which is available for all types of misrepresentation, even if wholly innocent. Certain bars, such as lapse of time, or the intervention of third party rights, will prevent rescission being available.

Rescission of the contract. This is the main remedy which is available for all types of misrepresentation, even if wholly innocent. Certain bars, such as lapse of time, or the intervention of third party rights, will prevent rescission being available.

Damages at common law. Damages are only available at common law if the maker of the statement has acted fraudulently, or been negligent in one of the limited situations where there is a duty of care (under the Hedley Byrne v Heller principle).

Damages at common law. Damages are only available at common law if the maker of the statement has acted fraudulently, or been negligent in one of the limited situations where there is a duty of care (under the Hedley Byrne v Heller principle).

Damages under the Misrepresentation Act 1967, s 2(1). This is the most powerful remedy available, providing damages unless the maker of the misrepresentation can prove that there were reasonable grounds for him or her to believe in the truth of the statement.

Damages under the Misrepresentation Act 1967, s 2(1). This is the most powerful remedy available, providing damages unless the maker of the misrepresentation can prove that there were reasonable grounds for him or her to believe in the truth of the statement.

Exclusion of liability for misrepresentation

Exclusion of liability for misrepresentation

Exclusion of liability is governed by s 3 of the Misrepresentation Act 1967, which requires such clauses to satisfy the ‘requirement of reasonableness’.

Exclusion of liability is governed by s 3 of the Misrepresentation Act 1967, which requires such clauses to satisfy the ‘requirement of reasonableness’.

Entire agreement’ clauses may prevent contractual liability for pre-contractual statements, but cannot circumvent s 3 of the 1967 Act.

Entire agreement’ clauses may prevent contractual liability for pre-contractual statements, but cannot circumvent s 3 of the 1967 Act.

This chapter and the next three deal with problems which may arise out of behaviour that takes place prior to a contract being formed. A party to a contract may, after a valid agreement has apparently been concluded, nevertheless decide that it has turned out not to be quite what was anticipated, or that the behaviour of the other party means that it should not be enforced. This may be the result of false information, a mistake as to some aspect of what was agreed, the imposition of threats, or the application of improper pressure. These situations are dealt with by the English law of contract by rules which are traditionally grouped under the headings ‘misrepresentation’, ‘mistake’, ‘duress’ and ‘undue influence’. In such a situation, the party who is unhappy with the agreement may wish to escape from it altogether, or to seek compensation of some kind. This chapter discusses the rules relating to ‘misrepresentation’ which allow for such an eventuality. The other areas are covered in the subsequent chapters.

An issue central to the consideration of these areas is the level of responsibility placed on parties during negotiations. The European Draft Common Frame of Reference deals specifically with negotiations in Art II.-3.301. This is headed ‘Negotiations contrary to good faith and fair dealing’ and contains the following four paragraphs:

(1) A party is free to negotiate and is not liable for failure to reach an agreement.

(2) A person who is engaged in negotiations has a duty to negotiate in accordance with good faith and fair dealing and not to break off negotiations contrary to the duty of good faith and fair dealing. This duty may not be excluded or limited by contract.

(3) A person who is in breach of the duty is liable for any loss caused to the other party by the breach.

(4) It is contrary to good faith and fair dealing, in particular, for a party to enter into or continue negotiations with no real intention of reaching an agreement with the other party.

The Article recognises that negotiation is an important part of contractual dealings, but that such negotiations do not always lead to a contract. There is nothing inherently wrong in negotiations breaking down. Parties should be allowed to explore the possibilities of making an agreement without the need to feel under any obligation to end up in a contract with each other. This view is also that taken by English contract law. The Article goes further, however, and in paras 3 and 4 makes a party who, in negotiating, is not genuinely trying to reach an agreement liable for any losses which such behaviour may cause to the other party. This positive obligation is not recognised by English law and ‘time-wasters’ are free to back away from a contract without penalty. Similarly, para 2 of the Article, which is probably the most significant provision, has the effect of placing a positive duty on parties to negotiate in accordance with principles of ‘good faith and fair dealing’. There are two points of contrast here with English law. First, the Article treats the negotiating process as a discrete entity, with liabilities arising irrespective of whether a contract is made. In general, under English law there is no liability for wrongdoing during negotiation unless the parties end up having made a contract.1 Second, the duty is a positive one. In English law the duties in relation to negotiation are primarily negative.2 That is, the law intervenes when a person has behaved in a way which leads to the breach of a particular rule; it does not generally do so where a person has failed to act in a way which would have been beneficial to the other side.3

8.2.1 IN FOCUS: SHOULD THERE BE AN OBLIGATION TO NEGOTIATE ‘IN GOOD FAITH’?

The notion of positive obligations of ‘good faith and fair dealing’ in the performance of contractual obligations are common in other systems of law,4 including some common law systems,5 though they do not always extend to the negotiation stage. The concept had very limited recognition, however, under the classical law of contract.6 It is now being introduced through the influence of European directives, such as those concerned with unfair terms in consumer contracts7 or the rights of commercial agents.8 The regulations giving effect to these directives have used the language of good faith, and the English courts are therefore having to get to grips with it.9 As yet, this has not led to any general move to develop good faith principles in areas not directly covered by such regulations. In particular, in relation to pre-contractual statements, which are the main concern of this chapter, the obligation is in general not to tell lies, rather than to tell the truth.

Why should this be the case? Why did the classical English law of contract not impose an obligation on contracting parties to be open with each other in negotiations, and to reveal all information which is relevant to their contract? There are two main answers that may be given to this question. The first is that such a positive obligation would not have sat easily with the archetype of a contract which tended to form the basis of the classical analysis. This was of two business people, of equal bargaining power, negotiating at arm’s length. In such a situation, the court’s attitude, based on ‘freedom of contract’, is that they should as far as possible be left to their own devices. If one of the parties requires information prior to a contract, then that party should ask questions of the other party. If what is then said in response turns out to be untrue, then legal liability will follow, but if no such request for information has been made, then it is not the court’s business to say to the silent party ‘you should have realised that this information would have been important to the other side, and you should therefore have disclosed it’.

The second answer is based on ‘economic efficiency’. Information is valuable, and those in possession of it should not necessarily be required to disclose it. If, for example, a purchaser has spent money on extensive market research and is aware that there is a demand for a particular product in a particular market, it would not make economic sense (in a system based on capitalism and free trade) to require the disclosure of that information. The purchaser is enabled, by the use of the information, to buy goods at a price that is acceptable to the seller, and then resell them at a profit in the market that the purchaser has discovered. If the purchaser had to disclose the information to the seller in that situation, the point of having done the market research would be lost. In other words, disclosure would discourage entrepreneurial activity designed to increase economic activity, and thereby increase wealth.10

There is obviously some strength in this argument, but two notes of caution should be sounded. First, it is now recognised that it is not always legitimate to make use of information that can be turned to economic advantage. In the area of share dealing, for example, the use of ‘insider information’ is now regarded as so undesirable that in certain circumstances to do so is treated as a criminal offence.11 Second, the archetypal model does not, of course, conform to the reality of much contractual dealing. Most obviously, many, if not the majority, of contracts are made between parties who are unequal – most obviously when the contract is business to consumer, but also in many business to business contracts. Withholding information that disadvantages the weaker party in such a situation may well be regarded as unacceptable. Moreover, even where business contractors are more or less equal partners, it does not necessarily make economic sense to conceal information from the other side. Where the contract is a long-term, ‘relational’ one, or where it is expected that the two contracting parties will want to do business with each other in the future, acting in a way which the other side may see as ‘taking an unfair advantage’ is probably not a sensible policy.12 Even where there is no such continuing relationship, it may not be advantageous to gain a reputation for sharp dealing, since this is likely to discourage other potential contractual partners. It is likely, therefore, that business practice will in fact be more open than might be assumed from a rigid application of the ‘economic efficiency’ model. If that is the case, and the courts are professing to operate commercial law in a way that reflects the way in which business people actually conduct their relationships, a greater recognition of the value of openness would be justifiable.

8.2.2 OTHER REMEDIES FOR PRE-CONTRACTUAL STATEMENTS

It should be noted that there are some situations where Parliament has intervened, generally in consumer contracts,13 to impose an obligation of disclosure. An example is the requirement under the Consumer Credit Act 1974 that the interest charged for credit should be presented to the potential debtor in a standardised form (the ‘APR’) which assists in making comparisons between the terms offered by different lenders.14 There are also some situations where, independent of any possible liability for misrepresentation, criminal liability is attached to making misleading statements to potential contractors.15 These controls over pre-contractual statements are not discussed further here.

A further civil remedy for certain types of statement inducing a contract (that is, those which can be put into the form of a promise) may be available where the promise can be found to form part of a collateral unilateral contract, of the form ‘If you enter into a contract with me, I promise you X’. This has been discussed in Chapters 5 and 6,16 and is not considered further here.

The law relating to misrepresentation is concerned with the situation in which a false statement leads a contracting party to enter into a contract that would otherwise not have been undertaken. It provides in certain circumstances for the party whose actions have been affected to escape from the contract or claim damages (or both). There are a number of possible actions. The contract may be rescinded under the common law. Damages may be recovered under the Misrepresentation Act 1967. The tort actions for deceit, or negligent misstatement,17 may provide alternative bases for the recovery of damages.

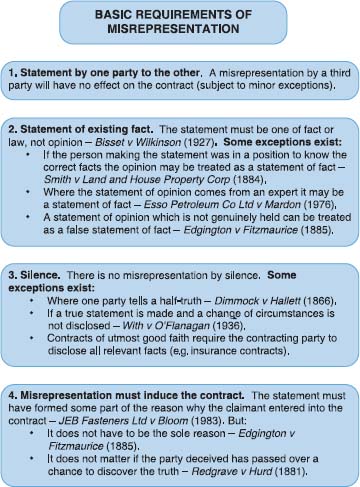

The basic requirements that are necessary in order for there to be a contractual remedy for a misrepresentation are as follows: the false statement must have been made by one of the contracting parties to the other; it must be a statement of fact or law, not opinion; and the statement must have induced the other party to enter into the contract. These elements will be considered in turn.

8.3.1 STATEMENT BY ONE PARTY TO THE OTHER

Where a claimant is seeking to rescind a contract on the basis of a misrepresentation, or to recover damages under s 2 of the Misrepresentation Act 1967,18 the normal rule is that the false statement must have been made by, or on behalf of,19 the other contracting party. If a person has entered into a contract on the basis of a misrepresentation by a third party, this will have no effect on the contract, or on the person’s legal relationship with the other contracting party. A person who buys shares in a company, on the basis of a third party’s statement that it has just made a substantial profit, cannot undo the share purchase if the statement turns out to be untrue.

Figure 8.1

This general principle has been affected, at least in certain circumstances, however, by the House of Lords’ decision in Barclays Bank v O’Brien.20 In this case, a husband made a misrepresentation to his wife as to the extent to which the matrimonial home was being used as security for his business debts. On the basis of this misrepresentation, the wife entered into a contract of guarantee with the bank, using the house as security. The House of Lords held that because the bank should have been aware of the risk of misrepresentation by the husband, but had taken no steps to encourage the wife to take independent legal advice, it could not enforce the contract of guarantee against her.21 In effect, therefore, a misrepresentation made by a person who was not the other contracting party was being used to rescind the contract. This decision and subsequent case law is discussed in detail in Chapter 11.22 There is no reason to expect it to result in a broad exception to the general principle stated above. It does open the door, however, to similar arguments in other circumstances where a party may reasonably expect a third party to make misrepresentations.23

If the claimant is simply seeking damages rather than rescission of the contract, the actions for deceit or negligent misstatement at common law may be available,24 even if the statement was not made by or on behalf of the other party to the contract.

8.3.2 STATEMENT OF EXISTING FACT OR LAW

In relation to the actions for rescission, deceit or under the Misrepresentation Act 1967, the statement must be one of fact or law, not opinion.25

Key Case Bisset v Wilkinson (1927)26

Facts: A farmer in New Zealand told the plaintiff, a prospective purchaser of his land, that it would support 2,000 sheep. The plaintiff bought the land but it failed to support 2,000 sheep. He sought to rescind the contract on the ground of misrepresentation.

Held: The Privy Council held that this was not a misrepresentation, even though it turned out to be inaccurate. Neither the farmer, nor anyone else, had at any point carried on sheep farming on the land, and the purchaser was aware of this. The farmer’s view on the matter was no more than an expression of opinion, and not a statement of fact. Rescission was refused.

For Thought

What do you think the outcome of Bisset v Wilkinson would have been if the farmer had been experienced in sheep farming, though he had never farmed sheep on this particular land?

The courts have recognised three situations where a statement which appears to be one of opinion can nevertheless be treated as one of fact. First, the opinion must not be contradicted by other facts known to the person giving it. In Smith v Land and House Property Corp,27 the statement that a tenant was ‘most desirable’, while on its face an opinion, was treated as a misrepresentation because the maker of the statement knew that the tenant had in fact been in arrears with his rent for some time. Second, where the statement of opinion comes from an ‘expert’, it may amount to a representation that the expert has based it on a proper consideration of all the relevant circumstances. In Esso Petroleum Co Ltd v Mardon,28 a representative of Esso gave a view as to the likely throughput of petrol at a particular petrol station. In giving this estimate, however, the representative had overlooked the fact that the conditions imposed by the local planning authority meant that the petrol station would not have a frontage on the main road. The statement as to the likely throughput was clearly at one level an opinion. The Court of Appeal, however, took the view that in the circumstances it involved a representation that proper care had been taken in giving it, and that this was a statement of fact. Third, a statement of opinion that is not genuinely held can be treated as a false statement of fact in relation to the person’s state of mind. This derives from the view expressed in Edgington v Fitzmaurice29 that a statement of an intention to act in a particular way in the future may be interpreted as a statement of fact, if it is clear that the person making the statement did not, at that time, have any intention of so acting.

Key Case Edgington v Fitzmaurice (1885)

Held: The Court of Appeal held that this statement of intention could be treated as a representation as to the directors’ state of mind at the time that the prospectus was issued, and could thus be treated as a statement of fact. As Bowen LJ put it:30

… the state of a man’s mind is as much a fact as the state of his digestion. It is true that it is very difficult to prove what the state of a man’s mind at a particular time is, but if it can be ascertained it is as much a fact as anything else. A misrepresentation as to the state of a man’s mind is, therefore, a misstatement of fact.

The directors, by misrepresenting their actual intentions, were making a false statement of fact.

A similar lack of belief in the truth of what is being said may also turn a statement of opinion into a misrepresentation. It is a false statement of the person’s current state of mind.

It was traditionally thought that a false statement of law was not to be treated as a statement of fact for the purposes of misrepresentation.31 This point has been reconsidered, however, in the light of the House of Lords’ decision in Kleinwort Benson Ltd v Lincoln City Council.32 Here the House overturned the long-held view that mistakes of law could not be used as the basis for an action for restitution of money paid. It had previously been thought that this was only available in relation to mistakes of fact. If the courts have here assimilated ‘law’ to ‘fact’, it seems that the same should apply to misrepresentations. This was the view taken by the High Court in Pankhania v Hackney London Borough Council,33 in which the judge held that the ‘misrepresentation of law’ rule has not survived Kleinwort.34 He took the view that:

The distinction between fact and law in the context of relief from misrepresentation has no more underlying principle to it than it does in the context of relief from mistake. Indeed, when the principles of mistake and misrepresentation are set side by side, there is a stronger case for granting relief against a party who has induced a mistaken belief as to law in another, than against one who has merely made the same mistake himself … The survival of the ‘misrepresentation of law’ rule following the demise of the ‘mistake of law’ rule would be no more than a quixotic anachronism.

A misrepresentation can be made by actions as well as words. This is illustrated by the case of Spice Girls Ltd v Aprilia World Service BV.35 Spice Girls Ltd, the company formed to promote the pop group, the Spice Girls, was in the process of making a contract for the promotion of Aprilia’s scooters. Shortly before the contract was signed, the members of the group all took part in the filming of a commercial for Aprilia. At that time, they knew that one member of the group intended to leave, as she did shortly after the contract had been signed. The group’s participation in the filming was held to amount to a representation that Spice Girls Ltd did not know and had no reasonable ground to believe that any of the existing members had at that time a declared intention to leave. This was untrue, and therefore the participation in the filming amounted to a misrepresentation by conduct.

8.3.3 MISREPRESENTATION BY SILENCE

In general, there is no misrepresentation by silence. Even where one party is aware that the other is contracting on the basis of a misunderstanding of some fact relating to the contract, there will generally be no liability. This is in line with the general approach outlined at the beginning of this chapter, that English law imposes a negative obligation not to tell falsehoods, rather than a positive obligation to tell the truth.

There are, however, some exceptions to this. First, the maker of the statement must not give only half the story on some aspect of the facts. Thus, in Dimmock v Hallett,36 the statement that flats were fully let when, in fact, as the maker of the statement knew, the tenants had given notice to quit was capable of being a misrepresentation.37 Second, if a true statement is made, but then circumstances change, making it false, a failure to disclose this will be treated as a misrepresentation.

Key Case With v O’Flanagan (1936)38

Facts: A doctor was seeking to sell his practice. He told a prospective purchaser that the practice’s income was £2,000 per annum. This was true at the time, but as a result of the vendor’s illness the practice declined considerably over the next few months, so that by the time it was actually sold, its value had reduced significantly, and takings were averaging only £5 per week. The purchaser sought to rescind the contract.

Held: The Court of Appeal held that the failure to notify the purchaser of the fact that the earlier statement was no longer true amounted to a misrepresentation.39 The purchaser was entitled to rescind the contract.

The third situation in which silence can constitute a misrepresentation is in relation to certain contracts, such as those for insurance,40 which are treated as being ‘of the utmost good faith’ (uberrimae fidei), and require the contracting party to disclose all relevant facts. In an insurance contract, for example, there is an obligation to disclose material facts, even if the other party has not asked about them. Thus, in Lambert v Co-operative Insurance Society,41 a woman who was renewing the insurance on her jewellery should have disclosed that her husband had recently been convicted of conspiracy to steal. The fact that she had not mentioned this meant that, when some of her jewellery was subsequently stolen, the insurance company was entitled not to compensate her under the policy. The obligation is to disclose such facts as a reasonable insurer might have treated as material.42 The test of materiality does not always seem to be applied very strictly, however. In Woolcutt v Sun Alliance and London Insurance Ltd,43 a policy for fire insurance on a house was invalidated because the insured had failed to disclose in a mortgage application, which indicated that the mortgagee would insure the property concerned, that he had been convicted of robbery some 10 years previously. It is not immediately obvious why this fact was material. Caulfield J simply treated it as ‘almost self-evident’ that ‘the criminal record of the assured can affect the moral hazard which the insurers have to assess’.44

The obligation most frequently operates to the disadvantage of the insured person, but that it can also apply to the insurer was confirmed by the House of Lords in Banque Financière v Westgate Insurance,45 which concerned the failure by the insurer to disclose wrongdoing by its agent. A similar obligation applies to contracts establishing family settlements. Thus, in Gordon v Gordon,46 a settlement was made on the presumption that an elder son was born outside marriage, and was therefore illegitimate. In fact, the younger son knew that his parents had been through a secret marriage ceremony prior to the birth of his elder brother. The fact that he had concealed this knowledge, which was clearly material, meant that the settlement had to be set aside.

Finally, there are some contracts that involve a fiduciary relationship, and this may entail a duty to disclose. In this category are to be found contracts between agent and principal,47 solicitor and client, and a company and its promoters.48 Other similar relationships which have a fiduciary character will be treated in the same way, and the list is not closed.

8.3.4 MISREPRESENTATION MUST INDUCE THE CONTRACT

It is not enough to give rise to a remedy for misrepresentation for the claimant to point to some false statement of fact made by the defendant prior to a contract which they have made. It must also be shown that that statement formed some part of the reason why the claimant entered into the agreement. In JEB Fasteners Ltd v Bloom,49 for example, which was concerned with this issue of reliance in the context of an action for negligent misstatement at common law, it was established that the plaintiffs took over a business having seen inaccurate accounts prepared by the defendants. Their reason for taking over the business, however, was shown to have been the wish to secure the services of two directors. The accounts had not induced their action in taking over the business. Similarly, where the claimant has not relied on the statement, but has sought independent verification, there will not be sufficient reliance to found an action.50

On the other hand, it is not necessary for the misrepresentation to be the sole reason why the contract was entered into. In Edgington v Fitzmaurice,51 the plaintiff was influenced not only by the prospectus, but also by his own mistaken belief that he would have a charge on the assets of the company. His action based on misrepresentation was nevertheless successful. Provided the misstatement was ‘actively present to his mind when he decided to advance the money’, then it was material. The test is, according to Bowen LJ:52

… what was the state of the plaintiff’s mind, and if his mind was disturbed by the misstatement of the defendants, and such disturbance was in part the cause of what he did, the mere fact of his also making a mistake himself could make no difference.

Nor does it matter that the party deceived has spurned a chance to discover the truth. In Redgrave v Hurd,53 false statements were made by the plaintiff about the income of his practice as a solicitor, on the strength of which the defendant had entered into a contract to buy the plaintiff’s house and practice. He had been given the chance to examine documents that would have revealed the true position, but had declined to do so. This did not prevent his claim based on misrepresentation.

For Thought

Doesn’t this approach seem to encourage contracting parties not to make proper inquiries before entering into a contract? In other words, is the law rewarding carelessness?

The principle adopted in Redgrave v Hurd will not be applied, however, where the true position was set out in the contract signed by the claimant. In Peekay Intermark Ltd v Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd54 a representative of the defendant bank had described an investment opportunity to the claimant in general terms. Some days later the representative sent to the claimant the full terms and conditions of the investment. This contract contained provisions that made the investment more risky than it appeared from the initial broad description given by the representative. The claimant looked over the documents briefly, and initialled them, but did not read them in detail, assuming that they were in line with what he had been previously told. He subsequently sought damages under s 2(1) Misrepresentation Act 1967 on the basis of the representative’s negligent misrepresentation of the terms. He succeeded at first instance, but on appeal, the Court of Appeal held for the defendant. It ruled that although the documents sent to the claimant did not correspond to the investment previously outlined by the representative, the defendants had not misrepresented the documents themselves. Since the claimant had looked at and signed these documents, it was not then open to him to claim that he was induced to sign by an earlier misrepresentation.

It seems that if the statement is one on which a reasonable person would have relied, then there is a rebuttable presumption that the claimant did in fact rely on it. This was the view of the Court of Appeal in Barton v County NatWest Ltd.55 Moreover, the presumption will not disappear simply as a result of the fact that the claimant has given evidence; the burden remains on the defendant to disprove it.

The contrary position – that is, where it is claimed that the claimant did in fact rely on the statement, even though a reasonable person would not have done so – has also been given some consideration. In other words, does the reliance on the statement have to be ‘reasonable’ in order for it to be a material inducement to contract? This issue was considered in Museprime Properties Ltd v Adhill Properties Ltd.56 Property owned by the defendant was sold by auction to the plaintiffs. There was an inaccurate statement in the auction particulars, which was reaffirmed by the auctioneer, to the effect that rent reviews of three leases to which the properties were subject had not been finalised. The plaintiffs sought to rescind the contract for misrepresentation. The defendants argued, as part of their case, that the misrepresentation was not material because no reasonable bidder would have allowed it to influence his bid. Scott J held (approving a passage to this effect in Goff and Jones, 1993)57 that the materiality of the representation was not to be determined by whether a reasonable person would have been induced to contract. As long as the claimant was in fact induced, as was the case here, that was enough to entitle him to rescission. The reasonableness or otherwise of his or her behaviour was relevant only to the burden of proof: the less reasonable the inducement, the more difficult it would be for the claimant to convince the court that he or she had been affected by the misrepresentation.

The position is apparently different, however, in relation to insurance contracts. Where the case is one of non-disclosure in such a contract (which is a contract uberrimae fidei – requiring the utmost good faith), the test is whether a reasonable insurer would have relied on the misrepresentation. This was the view of the House of Lords in Pan Atlantic Insurance Co Ltd v Pine Top Insurance Co Ltd.58

8.3.5 IN FOCUS: HOW UNREASONABLE CAN A PURCHASER BE?

It is difficult to be sure how far the principle that, apart from insurance contracts, the reaonableness or otherwise of reliance on a misrepresentation is irrelevant can be taken. Suppose, for example, I am selling my car and, prior to the contract, I tell the prospective purchaser that the car is amphibious and will go across water. Can the purchaser later claim against me because this ridiculous statement turns out to be untrue, as he has discovered now that the car is at the bottom of the river? Clearly, there may be difficulties of proving that there was reliance in fact, as noted above, but assuming that it is established that the statement was believed by the purchaser (for example, by the fact that he tried to drive across a river), the Museprime approach would give a remedy in misrepresentation. Would the courts go this far? Or would some degree of reasonable reliance be introduced, where, for example, no reasonable person would ever have believed the statement to be true?