MENTAL CAPACITY DEFENCES

AIMS AND OBIECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should be able to:

Understand the law on insanity and automatism

Understand the law on insanity and automatism

Understand the law on intoxication

Understand the law on intoxication

Analyse critically the scope and limitations of the mental capacity defences and the reform proposals

Analyse critically the scope and limitations of the mental capacity defences and the reform proposals

Apply the law to factual situations to determine whether liability can be avoided by invoking a defence

Apply the law to factual situations to determine whether liability can be avoided by invoking a defence

9.1 Insanity

Although the insanity defence is rarely used and is therefore of little real practical significance, it nevertheless raises fundamental questions about criminal responsibility and the role of criminal law in dealing with violent people. Its importance had been much reduced, particularly in murder cases, by two developments:

the introduction of the diminished responsibility defence in 1957 (see Chapter 10)

the introduction of the diminished responsibility defence in 1957 (see Chapter 10)

the abolition of the death penalty in 1965

the abolition of the death penalty in 1965

It is a general defence and may be pleaded as a defence to any crime requiring mens rea (including murder), whether tried on indictment in the Crown Court or summarily in the magistrates’ court (Horseferry Road Magistrates’ Court, ex parte K (1996) 3 All ER 719). However, it is not, apparently, a defence to crimes of strict liability (see Chapter 4). In DPP v H (1997) 1 WLR 1406, the High Court held that insanity was no defence to a charge of driving with excess alcohol contrary to s 5 of the Road Traffic Act 1988. Medical evidence that D was suffering manic depressive psychosis with symptoms of distorted judgment and impaired sense of time and of morals at the time of the offence was, therefore, irrelevant.

9.1.1 Procedure

Often D does not specifically raise the defence of insanity but places the state of his mind in issue by raising another defence such as automatism. The question whether such a defence, or a denial of mens rea, really amounts to the defence of insanity is a question of law to be decided by the judge on the basis of medical evidence (Dickie (1984) 3 All ER 173). Whether D, or even his medical witnesses, would call it insanity or not is irrelevant. According to Lord Denning in Bratty v Attorney-General of Northern Ireland (1963) AC 386, in such cases the prosecution may — indeed must — raise the issue of insanity.

Importance of medical evidence

If the judge decides that the evidence does support the defence, then he should leave it to the jury to determine whether D was insane (Walton (1978) 1 All ER 542). In practice, the evidence of medical experts is critically important. Section 1 of the Criminal Procedure (Insanity and Unfitness to Plead) Act 1991 provides that a jury shall not return a special verdict (see below) except on the written or oral evidence of two or more registered medical practitioners, at least one of whom is approved as having special expertise in the field of medical disorder.

9.1.2 The special verdict

If D is found to have been insane at the time of committing the actus reus, then the jury should return a verdict of ‘not guilty by reason of insanity’ (s 1 Criminal Procedure (Insanity) Act 1964), otherwise referred to as the special verdict. Until quite recently this verdict obliged the judge to order D to be detained indefinitely in a mental hospital. In many cases the dual prospect of being labelled ‘insane’ and indefinite detention in a special hospital such as Broadmoor or Rampton discouraged defendants from putting their mental state in issue. In some cases it led to guilty pleas to offences of which defendants were probably innocent (Quick (1973) QB 910; Sullivan (1984) AC 156; Hennessy (1989) 1 WLR 287, all of which will be considered below).

The Criminal Procedure (Insanity and Unfitness to Plead) Act 1991

The position described above was modified by the 1991 Act. The Act made a number of changes but, most significantly, substituted a new s 5 into the Criminal Procedure (Insanity) Act 1964. The new section allowed the judge considerable discretion with regard to disposal on a special verdict being returned. That section has since been replaced by another version of s 5 following the enactment of the Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004. Now, following a special verdict, the judge may make either

a.a hospital order (with or without a restriction order)

b.a supervision order, or

c.an order for absolute discharge.

This is particularly useful where the offence is trivial and/or the offender does not require treatment. The new power was first utilised in Bromley (1992) 142 NLJ 116.

This new power does not, however, apply to murder cases when indefinite hospitalisation is unavoidable. However, as noted above, defendants charged with murder are far more likely to plead diminished responsibility under s 2 of the Homicide Act 1957 than insanity.

9.1.3 The M’Naghten rules

The law of insanity in England is contained in the M’Naghten Rules, the result of the deliberations of the judges of the House of Lords in 1843. Media and public outcry at one Daniel M’Naghten‘s acquittal on a charge of murder led to the creation of rules to clarify the situation. Lord Tindal CJ answered on behalf of himself and 13 other judges, while Maule J gave a separate set. The Rules are not binding as a matter of strict precedent. Nevertheless, the Rules have been treated as authoritative of the law ever since (Sullivan (1984)). The Rules state as follows:

QUOTATION

‘The jurors ought to be told in all cases that every man is presumed to be sane, and to possess a sufficient degree of reason to be responsible for his crimes, until the contrary be proved to their satisfaction; and that to establish a defence on the ground of insanity it must be clearly proved that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing, or, if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.’

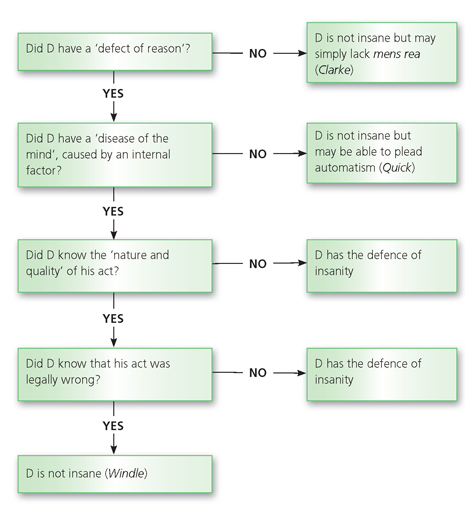

The Rules can be broken down into three distinct elements, all of which must be established.

Defect of reason

Defect of reason

Disease of the mind

Disease of the mind

Not knowing what D was doing or not knowing that it was ‘wrong’

Not knowing what D was doing or not knowing that it was ‘wrong’

Because of the presumption of sanity, the burden of proof is on the defence (albeit on the lower standard, the balance of probabilities).

Defect of reason

The phrase ‘defect of reason’ was explained in Clarke (1972) 1 All ER 219 by Ackner J, who said that it referred to people who were ‘deprived of the power of reasoning’. It did not apply to those who ‘retain the power of reasoning but who in moments of confusion or absent-mindedness fail to use their powers to the full’.

JUDGMENT

‘The M’Naghten Rules relate to accused persons who by reason of a “disease of the mind” are deprived of the power of reasoning. They do not apply and never have applied to those who retain the power of reasoning but who in moments of confusion or absent-mindedness fail to use their powers to the full.’

CASE EXAMPLE

Clarke (1972) 1 All ER 219

Disease of the mind

‘Disease of the mind’ is a legal term, not a medical term. In Kemp (1957) 1 QB 399, D suffered from arteriosclerosis (hardening of the arteries) which restricted the flow of blood to the brain, causing blackouts. In this condition he committed the actus reus of grievous bodily harm (GBH) (he hit his wife with a hammer). The question arose whether arteriosclerosis supported the defence of automatism or insanity. Devlin J decided that it was a case of insanity. He stated:

JUDGMENT

‘The law is not concerned with the brain but with the mind, in the sense that ‘mind’ is ordinarily used, the mental faculties of reason, memory and understanding. If one read for “disease of the mind” “disease of the brain”, it would follow that in many cases pleas of insanity would not be established because it could not be proved that the brain had been affected in any way, either by degeneration of the cells or in any other way. In my judgment the condition of the brain is irrelevant and so is the question whether the condition is curable or incurable, transitory or permanent.’

Thus, if D suffers from a condition (not necessarily a condition of the brain) which affects his ‘mental faculties’, then this amounts to the defence of insanity. The problem is, how to distinguish such cases from situations when D suffers some temporary condition (eg concussion following a blow to the head). In the latter situation, D loses his ‘mental faculties’, but the problem is extremely unlikely to repeat itself and so ordering hospitalisation or treatment would be pointless. Hence, in such cases the true defence is automatism (see below). In order to distinguish cases of insanity from cases of automatism, the courts have adopted a test based on whether the cause of D’s ‘defect of reason’ was internal or external (such as the blow to the head example). In Quick (1973), Lawton LJ said:

JUDGMENT

‘Our task has been to decide what the law now means by the words “disease of the mind”. In our judgment the fundamental concept is of a malfunctioning of the mind caused by disease. A malfunctioning of the mind of transitory effect caused by the application to the body of some external factor such as violence, drugs, including anaesthetics, alcohol and hypnotic influences cannot fairly be said to be due to disease.’

This case should be contrasted with that of Hennessy (1989).

CASE EXAMPLE

Hennessy (1989) 1 WLR 287

D, a diabetic, had forgotten to take his insulin. He suffered what is known medically as hyperglycaemia (high blood sugar). In this condition he was seen by police officers driving a car that had been reported stolen. D was charged with two counts of taking a motor vehicle without consent and driving a motor vehicle while disqualified. D testified that he could not remember taking the car and driving it away. The trial judge declared that the evidence supported a defence of insanity. D changed his plea to guilty and appealed. However, distinguishing Quick, the Court of Appeal confirmed that hyperglycaemia was caused by an internal factor, namely diabetes, and was therefore a disease of the mind. The correct verdict was insanity.

Two criticisms may be made here.

A relatively common medical condition (diabetes) is regarded by the criminal law as supporting a defence of insanity, with all the negative implications that that label conveys.

A relatively common medical condition (diabetes) is regarded by the criminal law as supporting a defence of insanity, with all the negative implications that that label conveys.

This is only the case in certain situations, namely when D suffers hyperglycaemia.

This is only the case in certain situations, namely when D suffers hyperglycaemia.

According to the Diabetes UK website, over 2.6 million people in the United Kingdom have been diagnosed with diabetes (and another 1/2 million people are estimated to have the condition without realising it). Does the decision in Hennessy mean that over 3 million people in the United Kingdom are legally insane? For more information refer to the ‘Internet links’ section at the end of this chapter. The problem associated with diabetes is not the only one created by the decision in Quick. According to the House of Lords, epileptics who suffer grand mal seizures and inadvertently assault someone nearby are also to be regarded as insane. This was seen in two cases: Bratty (1963) and Sullivan (1984).

CASE EXAMPLE

Sullivan (1984) AC 156

;D had suffered from epilepsy since childhood. He occasionally suffered fits. One day he was sitting in a neighbour’s flat with a friend, V. The next thing D remembered was standing by a window with V lying on the floor with head injuries. D was charged with assault. The trial judge ruled that the evidence that D had suffered a post-epileptic seizure amounted to a disease of the mind. To avoid hospitalisation, D pleaded guilty and appealed. Both the Court of Appeal and House of Lords upheld his conviction.

In Sullivan, Lord Diplock stated:

JUDGMENT

‘It matters not whether the aetiology of the impairment is organic, as in epilepsy, or functional, or whether the impairment itself is permanent or is transient and intermittent, provided that it subsisted at the time of the commission of the act. The purpose of the … defence of insanity … has been to protect society against recurrence of the dangerous conduct. The duration of a temporary suspension of the mental faculties … particularly if, as in Sullivan’s case, it is recurrent, cannot … be relevant to the application by the courts of the M’Naghten Rules.’

According to the Epilepsy Action website, 456, 000 people in the United Kingdom have epilepsy (this corresponds to one in every 131 people). In the event that any one of these people commits the actus reus of a crime, are they to be regarded as legally insane too? For more information, refer to the ‘Internet links’ section at the end of this chapter. Thus, diabetics (sometimes) and epileptics are regarded as ‘insane’ by English criminal law. What about someone who carries out the actus reus of a crime, such as assault, while sleepwalking? This was a question for the Court of Appeal in Burgess (1991) 2 QB 92. There was a persuasive precedent for deciding that this amounted to automatism (Tolson (1889) 23 QBD 168), but the Court of Appeal held that, after Quick (1973) and Sullivan, it had to be regarded as insanity. Lord Lane CJ stated that sleepwalking was ‘an abnormality or disorder, albeit transitory, due to an internal factor’.

CASE EXAMPLE

Burgess (1991) 2 QB 92

D and his friend, V, were in D’s flat watching videos. They both fell asleep but, during the night, D attacked V while she slept, hitting her with a wine bottle and a video recorder. She suffered cuts to her scalp which required sutures. To a charge of unlawful wounding contrary to s 20 OAPA 1861, D pleaded automatism, but the trial judge ruled he was pleading insanity and the jury returned the special verdict. The Court of Appeal dismissed D’s appeal.

According to a study carried out in Finland involving over 11, 000 people, some 4 per cent of women and 3 per cent of men sleepwalk (C Hublin et al., ‘Prevalence and Genetics of Sleepwalking’ (1997) 48 Neurology 177). With the UK population in excess of 59 million, this equates to approximately 2 million sleepwalkers in the United Kingdom alone. It is useful to note at this point that in Canada (which also uses the M’Naghten Rules), the Supreme Court has diverged from English law on this point. In Parks (1992) 95 DLR (4d) 27, D had carried out a killing and an attempted killing whilst asleep. However, the Supreme Court found that his defence was automatism. During the trial the defence had called expert witnesses in sleep disorders, whose evidence was that sleepwalking was not regarded as a neurological, psychiatric or any other illness, but a sleep disorder, quite common in children but also found in 2–2.5 per cent of adults. Furthermore, aggression while sleepwalking was quite rare and repetition of violence almost unheard of. Using this evidence, the Canadian Chief Justice, Lamer CJC, said that ‘Accepting the medical evidence, [D’s] mind and its functioning must have been impaired at the relevant time but sleepwalking did not impair it. The cause was the natural condition, sleep.’

CASE EXAMPLE

T (1990) Crim LR 256

D had been raped three days prior to carrying out a robbery and causing actual bodily i harm. She was diagnosed as suffering post-traumatic stress disorder, such that at the time of the alleged offences she had entered a dissociative state. The trial judge allowed automatism to be left to the jury, noting that ‘such an incident could have an appalling I effect on any young woman, however well-balanced normally’.

In Canada, meanwhile, a plea of dissociation was regarded as one of insanity. The difference was that in that case, the traumatic events leading up to the alleged dissociative state were much less distressing. In Rabey (1980) 114 DLR (3d) 193, D had developed an attraction towards a girl. When he discovered that she regarded him as a ‘nothing’, he hit her over the head with a rock and began to choke her. He was charged with causing bodily harm with intent to wound, and pleaded automatism, based on the psychologically devastating blow of being rejected by the girl. The trial judge accepted that D had been in a complete dissociative state. The prosecution doubted that D was suffering from such a state (the reality being that he was in an extreme rage) but that if he were then his condition was properly regarded as a disease of the mind. The trial judge ordered an acquittal based on automatism, but the appeal court allowed the prosecution appeal. The Supreme Court of Canada upheld that decision — the defence was insanity.

To summarise the law on ‘disease of the mind’, the following conditions have been held to support a plea of insanity (in England):

arteriosclerosis (Kemp (1957))

arteriosclerosis (Kemp (1957))

epilepsy (Sullivan (1984))

epilepsy (Sullivan (1984))

hyperglycaemia (high blood sugar: Hennessy (1989)) but not hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar: Quick (1973))

hyperglycaemia (high blood sugar: Hennessy (1989)) but not hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar: Quick (1973))

sleepwalking (Burgess (1991))

sleepwalking (Burgess (1991))

And in Canada, post-traumatic stress disorder caused by a relatively mundane event such as rejection by a prospective girlfriend (Rabey (1980)). In Australia, meanwhile, although the M’Naghten Rules have been adopted there, the internal/external factor test in Quick has not. In Falconer (1990) 171 CLR 30, Toohey J described the internal/external factor theory as ‘artificial’ and said that it failed to pay sufficient regard to ‘the subtleties surrounding the notion of mental disease’. In Australia, therefore, the distinction between insanity and automatism is found by identifying whether D’s mental state at the time of the actus reus was either

‘the reaction of an unsound mind to its own delusions, or to external stimuli, on the one hand’, which is insanity or

‘the reaction of an unsound mind to its own delusions, or to external stimuli, on the one hand’, which is insanity or

‘the reaction of a sound mind to external stimuli including stress-producing factors on the other hand’, which is automatism.

‘the reaction of a sound mind to external stimuli including stress-producing factors on the other hand’, which is automatism.

ACTIVITY

Applying the law

Nature and quality of the act

It seems there will be a good defence provided that when D acted he was not aware of, or did not appreciate, what he was actually doing, or the circumstances in which he was acting, or the consequences of his act. D’s lack of knowledge must be fundamental. Two famous old examples used to illustrate this point are

D cuts a woman’s throat but thinks (because of his ‘defect of reason’) that he is cutting a loaf of bread.

D cuts a woman’s throat but thinks (because of his ‘defect of reason’) that he is cutting a loaf of bread.

D chops off a sleeping man’s head because it would be amusing to see him looking for it when he wakes up.

D chops off a sleeping man’s head because it would be amusing to see him looking for it when he wakes up.

Obviously, in both these situations D does not know what he is doing and is entitled to the special verdict. If, on the contrary, D kills a man whom he believes, because of a paranoid delusion, to be possessed by demons, then he is still criminally responsible and not insane — his delusion has not prevented him from understanding that he is committing murder.

The act was wrong

What is meant here by ‘wrong’? Does it mean wrong as in ‘contrary to the criminal law’ or wrong as in ‘morally unacceptable’ — or perhaps both? In M’Naghten (1843) the Law Lords said that if D knew at the time of committing the actus reus of a crime that he ‘was acting contrary to law; by which expression we understand your lordships to mean the law of the land’, then he would not have the defence. This clearly suggested D will have the defence if he does not realise that he is committing a crime. The Court of Criminal Appeal in Windle (1952) 2 QB 826 confirmed this view of the word ‘wrong’. D had poisoned his wife and, on giving himself up to the police, said, ‘I suppose they will hang me for this?’ Despite medical evidence for the defence that he was suffering from a medical condition known as folie à deux, this statement showed that D was aware of acting unlawfully. D was convicted of murder. Lord Goddard CJ said:

JUDGMENT

‘Courts of law can only distinguish between that which is in accordance with law and that which is contrary to law … The law cannot embark on the question and it would be an unfortunate thing if it were left to juries to consider whether some particular act was morally right or wrong. The test must be whether it is contrary to law … [T]here is no doubt that in the M’Naghten Rules “wrong” means contrary to the law, and does not have some vague meaning which may vary according to the opinion of one man or of a number of people on the question of whether a particular act might or might not be justified.’

The position, therefore, is that if D knew his act was illegal, then he has no defence of insanity. This is the case even if he is suffering from delusions which cause him to believe that his act was morally right. This position has, however, been criticised. In 1975, the Royal Committee on Mentally Abnormal Offenders (Butler Committee) stated that the Windle definition of ‘wrong’ was ‘a very narrow ground of exemption since even persons who are grossly disturbed generally know that murder and arson, for instance, are crimes’.

In Johnson (2007) EWCA Crim 1978, the Court of Appeal was invited to reconsider the decision in Windle. However, although the court agreed that the decision in Windle was ‘strict’, they felt unable to depart from it, believing that, if the law was to be changed, it should be done by Parliament.

CASE EXAMPLE

Johnson (2007) EWCA Crim 1978

D suffered from delusions and auditory hallucinations. One day, armed with a large kitchen knife, he forced his way into V’s flat and stabbed him four times (fortunately, V recovered). Following his arrest, D was assessed by two psychiatrists who diagnosed him as suffering from paranoid schizophrenia. They agreed that D knew that his actions were against the law; however, one psychiatrist asserted that D did not consider what he had done to be ‘wrong in the moral sense’. The trial judge declined to leave the insanity defence to the jury, and D was convicted of wounding with intent. He appealed, but the Court of Appeal upheld his conviction.

Latham LJ stated:

JUDGMENT

‘The strict position at the moment remains as stated in Windle … This area, however, is a notorious area for debate and quite rightly so. There is room for reconsideration of rules and, in particular, rules which have their genesis in the early years of the 19th century. But it does not seem to us that that debate is a debate which can properly take place before us at this level in this case.’

In Stapleton (1952) 86 CLR 358, the High Court of Australia refused to follow Windle. That Court decided that morality, and not legality, was the concept behind the use of ‘wrong’. Thus in Australia the insanity defence is available if ‘through the disordered condition of the mind [D] could not reason about the matter with a moderate degree of sense and composure’. The same is true in Canada. In Chaulk (1991) 62 CCC (3d) 193, D had been charged with murder. Medical evidence showed that he suffered paranoid delusions such that he believed he had power to rule the world and that the killing had been a necessary means to that end. D believed himself to be above the law (of Canada). Finally, he deemed V’s death appropriate because he was a ‘loser’. The Supreme Court stated that ‘It is possible that a person may be aware that it is ordinarily wrong to commit a crime but, by reason of a disease of the mind, believes that it would be “right” according to the ordinary standards of society to commit the crime in a particular context. In this situation, [D] would be entitled to be acquitted by reason of insanity.’

9.1.4 Situations not covered by the rules

Irresistible impulse

Until the early twentieth century, a plea of irresistible impulse was a good defence under the M’Naghten Rules. In Fryer (1843) 10 Cl & F, the jury was directed that if D was deprived of the capacity to control his actions, it was open for them to find him insane. By 1925, however, the fact that D was unable to resist an impulse to act was held to be irrelevant, if he was nonetheless aware that his act was wrong. In Kopsch (1925) 19 Cr App R 50, D confessed to strangling his aunt with a necktie, apparently at her request. Upholding his conviction, Lord Hewart CJ described the defence argument, that a person acting under an uncontrollable impulse was not criminally responsible as a ‘fantastic theory’, which if it were to become part of the law, ‘would be merely subversive’. The reluctance of the courts to recognise a defence of irresistible impulse appears to be based on two grounds.

The difficulty of distinguishing between an impulse caused by insanity, and one motivated by greed, jealousy or revenge

The difficulty of distinguishing between an impulse caused by insanity, and one motivated by greed, jealousy or revenge

The view that the harder an impulse is to resist, the greater is the need for a deterrent

The view that the harder an impulse is to resist, the greater is the need for a deterrent

In 1953 the Royal Commission on Capital Punishment suggested, as an alternative to replacing the Rules altogether, adding a third limb, ie that D should be considered insane if at the time of his act he ‘was incapable of preventing himself from committing it…’. This was not taken up. However, irresistible impulse may support a defence of diminished responsibility (Byrne (1960) 2 QB 396). Thus, if D is charged

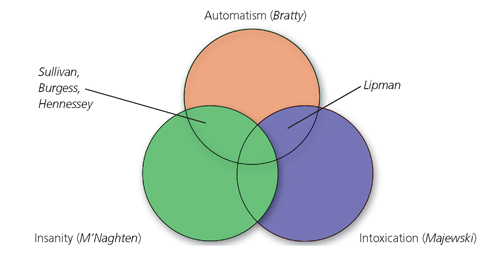

Figure 9.1 Insanity

9.1.5 Reform

In July 2012, the Law Commission (LC) published a ‘Scoping Paper’ on insanity (and automatism). In it, the LC pose a series of questions about the two defences to which they invite responses but do not propose any specific reform suggestions themselves. The purpose of the exercise is to ‘discover how in the criminal law the defences of insanity and automatism are working, if at all’. The LC state that they are ‘convinced’ that ‘there are significant problems with the law when examined from a theoretical perspective’. Once the LC has gathered responses to their questions, they will ‘consider how best to take the project forward to ensure that the law in practice is fit for purpose in the 21st century’. The Scoping Paper is available via the LC’s website, at http://lawcommission.justice.gov.uk/areas/insanity.htm.

KEY FACTS

Key facts on insanity as a defence

| Elements | Comment | Cases |

| Defect of reason | To be deprived of the power of reasoning | Clarke (1972) |

| Disease of the mind | Not concerned with the brain but with the mind Must derive from an internal source | Kemp (1957) Quick (1973) |

| Examples | Arteriosclerosis Epilepsy Hyperglycaemia Sleepwalking | Kemp (1957) Bratty (1963), Sullivan (1984) Hennessy (1989) Burgess (1991) |

| Not knowing what D was doing or not knowing that it was ‘wrong’ | ‘Wrong’ means legally wrong. | Windle (1952), Johnson (2007) |

| Burden of proof | It is for the defence to prove on the balance of probabilities. | |

| Effect of defence | Defendant is not guilty ‘by reason of insanity’ (the special verdict). | Unless charge was murder, judge has various disposal options: hospital order, supervision order, absolute discharge. If charge was murder, judge must order indefinite hospitalisation in a special hospital. |

9.2 Automatism

9.2.1 What is automatism?

‘Automatism’ is a phrase that was introduced into the criminal law from the medical world. There, it has a very limited meaning, describing the state of unconsciousness suffered by certain epileptics. In law it seems to have two meanings. According to Lord Denning in Bratty (1963):

JUDGMENT

‘Automatism … means an act which is done by the muscles without any control by the mind such as a spasm, a reflex action or a convulsion; or an act done by a person who is not conscious of what he is doing such as an act done whilst suffering from concussion or whilst sleepwalking.’

Conscious but uncontrolled

Here D is fully aware of what is going on around him but is incapable of preventing his arms, legs, or even his whole body from moving. In this sense, automatism is incompatible with actus reus: D is aware of what his body is doing but there is no voluntary act.

Impaired consciousness

In Bratty, Lord Denning arguably gave ‘automatism’ too narrow a definition in referring to D being ‘not conscious’. While automatism certainly includes unconsciousness, it is suggested that is should also include states of ‘altered’, ‘clouded’ or ‘impaired’ consciousness. If correct, this analysis suggests that automatism is a defence because it is incompatible with mens rea: D is not aware (or not fully aware) of what he is doing.

9.2.2 The need for an evidential foundation

If D wishes to plead automatism, it is necessary for him to place evidence in support of his plea before the court. The reasoning behind this rule was explained by Devlin J (as he then was) in Hill v Baxter (1958) 1 QB 277:

JUDGMENT

‘It would be quite unreasonable to allow the defence to submit at the end of the prosecution’s case that the Crown had not proved affirmatively and beyond a reasonable doubt that the accused was at the time of the crime sober, or not sleepwalking or not in a trance or black-out. I am satisfied that such matters ought not to be considered at all until the defence has provided at least prima facie evidence.’

More recently, in C (2007) EWCA Crim 1862, Moses LJ in the Court of Appeal said that ‘It is a crucial principle in cases such as this that D cannot rely on the defence of automatism without providing some evidence of it’. The evidence of D himself will rarely be sufficient, unless it is supported by medical evidence, because otherwise there is a possibility of the jury being deceived by spurious or fraudulent claims. In Bratty (1963), Lord Denning stated that it would be insufficient for D to simply say ‘I had a black-out’ because that was ‘one of the first refuges of a guilty conscience and a popular excuse’. He continued:

JUDGMENT

‘When the cause assigned is concussion or sleep-walking, there should be some evidence from which it can reasonably be inferred before it should be left to the jury. If it is said to be due to concussion, there should be evidence of a severe blow shortly beforehand. If it is said to be sleep-walking, there should be some credible support for it. His mere assertion that he was asleep will not suffice.’

9.2.3 Extent of involuntariness required

Must D’s control over his bodily movements be totally destroyed before automatism is available? How unconscious does D have to be before he can be said to be an automaton? It seems that the extent of involuntariness required to be established depends on the offence charged. There are two categories.

Crimes of strict liability

As we saw in Chapter 4, when D is charged with a strict liability offence, denial of mens rea is no defence, so a plea that D was unconscious would seem doomed to failure. D must therefore provide evidence that he was incapable of exercising control over his bodily movements. If, despite some lack of control, he was still able to appreciate what he was doing and operate his body to a degree, then the defence is not made out. The majority of cases in this area involve driving offences. In Isitt (1978) 67 Cr App R 44, Lawton LJ said:

JUDGMENT

‘The mind does not always operate in top gear. There may be some difficulty in functioning. If the difficulty does not amount to either insanity or automatism, is the accused entitled to say, “I am not guilty because my mind was not working in top gear”? In our judgment he is not … it is clear that the appellant’s mind was working to some extent. The driving was purposeful driving, which was to get away from the scene of the accident. It may well be that, because of panic or stress or alcohol, the appellant’s mind was shut to the moral inhibitions which control the lives of most of us. But the fact that his moral inhibitions were not working properly … does not mean that the mind was not working at all.’

In Isitt