Maritime Business During the Twentieth Century: Continuity and Change

Chapter 1

Maritime Business During the Twentieth Century: Continuity and Change

Gelina Harlaftis* and Ioannis Theotokas†

1. Introduction

The historical process is dynamic, and the changes that occurred during the course of world shipping in the past century, embedded some of the structures of the nineteenth century. The methodological tools of a historian and an economist will be used in this chapter, tracing continuity and change in the twentieth century shipping by examining maritime business at a macro-and micro level. At the core of the analysis lies the shipping firm, the micro-level, which helps us understand the changes in world shipping, the macro-level.

The shipping firm functions in a specific market, and the shipping market can only be understood as an international market, in a multiethnic environment. The first part of this chapter follows the developments in world shipping, analysing briefly the main fleets, the routes and cargoes carried, the ships and the main technological innovations. The second part provides an insight on the main structural changes in the shipping markets by focusing on the division of liner and tramp shipping. The third part reveals from inside the shipowning structure and its changes in time in the main twentieth century fleets: the British, the Norwegians, the Greeks and the Japanese; it is remarkable how similar their organisation and structure proves to be.1 Maritime business has always been an internationalised business. In the last five centuries of capitalist development, European colonial expansion was only made possible with the sea and ships; the sea being but a route of communication and strength rather than of isolation and weakness. Wasn’t it Sir Walter Raleigh in the late sixteenth century, one of Elizabeth’s main consultants who had set some of the first rules for the British expansion? “He who commands the sea commands the trade routes of the world. He who commands the trade routes, commands the trade. He who commands the trade, commands the riches of the world, and hence the world itself.” The real truths are tested in history and time.

2. Developments in World Shipping

There were two main developments in the nineteenth century that pre-determined the path of the world economies: an incredible industrialisation of the West and its dominance in the rest of the world. During that period the world witnessed an unprecedented boom in world exchange of goods and services, an unprecedented boom of international sea-trade. The basis of the world trade system of the twentieth century was consolidated in the nineteenth century: it was the flow of industrial goods from Europe to the rest of the world and the flow of raw materials to Europe from the rest of the world. In this way, deep-sea going trade became increasingly dominated by a small number of bulk commodities in all the world’s oceans and seas; in the last third of the nineteenth century, grain, cotton and coal were the main bulk cargoes that filled the holds of the world fleet. At the same time, the transition from sail to steam, apart from increasing the availability of cargo space at sea, caused a revolutionary decline in freight rates, contributing further to the increase of international sea-borne trade. Europe, however, remained at the core of the world sea-trade system: until the eve of the World War I, three quarters of world exports in value and almost two thirds of world imports concerned the old continent.2

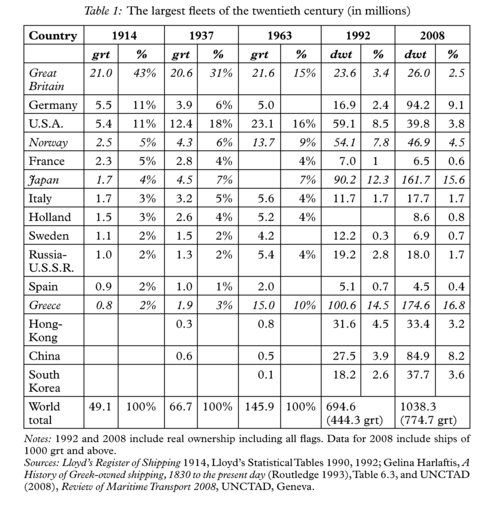

It does not come as a surprise then, that European countries owned the largest part of the ocean-going world fleet during this period. Due to technological innovations, the international merchant fleet was able to carry an increasing volume of cargoes between continents with greater speed and lower cost. By the turn of the twentieth century Great Britain was still the undisputable world maritime power owning 45% of the world fleet, followed by the United States, Germany, Norway, France and Japan, (see Table 1). Over 95% of the world fleet belonged to 15 countries that formed the so-called “Atlantic economy”; what is today called the “developed” nations of the OECD countries. Meanwhile, at the rival Pacific Ocean, Japan was preparing to be the rising star of world shipping in the twentieth century.

Pax Brittanica and the incredible increase of world economic prosperity of more than one hundred years closed abruptly with the beginning of World War I. The main cause was the conflict of the big industrial European nations for the expansion of their economic and political influence in the non-European world. It was the result of the competition of western European nations for new markets and raw materials that determined the nineteenth century and peaked in the beginning of the twentieth century as the influence of the industrialisation of western European nations became more distinct. At the beginning of the twentieth century almost all of Asia and Africa were in one way or another under European colonial control.

The factors that created the international economy of the nineteenth century proved detrimental during the two destructive world wars of the twentieth century by multiplying their effects. Firstly, the formation of gigantic national enterprises in Europe and the United States and their concentration in vast industrial complexes with continuous amalgamations of small and medium companies resulted in an exponential increase of world production. Second, the search for markets beyond Europe that would absorb the excessive industrial production, resulted in the fierce competition of British, German, French and American capital in international capital investments worldwide. The result was the creation of multinational companies and banks that led to the development of monopolies on a national and international level. Within this framework, the great expansion of the United States and German fleets took place, along with the multiple

mergers and acquisitions in the northern European liner shipping business and the gradual destruction of small tramp shipping companies, particularly in Great Britain.

The interwar economy never recovered from the shock of World War I that influenced the whole structure of the international economy resulting in the worst economic crisis that the industrial world had seen in 1929. During the interwar period world shipping faced severe problems stemming from a contracting world sea-trade, decreasing world immigration and increasing protectionism. The economic crisis did not affect the main national fleets in the same way. The impact was particularly felt in Britain. This is the period of the economic downhill of mighty old Albion. It was World War I that weakened Britain and allowed competitors to challenge its maritime hegemony. The withdrawal of British ships from trades not directly related to the Allied Cause opened the Pacific trades to the Japanese. Moreover, both Norway and Greece were neutrals, which meant that their fleets were able to profit from high wartime freight rates (Greece entered the war in 1917). Norwegian and Greek ships were able to trade at market rates for three years while most of the British fleet was requisitioned and forced to work for low, fixed remunerations. Freight rates in the free market remained high until 1920, after which they plummeted; while there was a brief recovery in the mid-1920s, the nadir was reached in the early 1930s.

Table 1 records the development of the world fleets of the main maritime nations from 1914 to 1937. During this period the world fleet increased at one third of its prewar size. The British fleet remained at the same level with a slight decrease of its registered tonnage, but its percentage of the ownership of the world fleet decreased from 43% to 31% due to the increase of the fleets of other nations. The interwar period was characterised by the unsuccessful attempt of the United States to keep a large national fleet with large and costly subsidies to shipping entrepreneurs. Most of the increase of the world fleet in the interwar period apart from the US was due to the Japanese, the Norwegians and the Greeks, who proved to be the owners of the most dynamic fleets of the century. Their growth was interconnected with the carriage of energy sources. The most important change in the world trade of the interwar period was the gradual decrease of the coal trade and the growing importance of oil.

The main coal producer (and exporter) in 1900 was the UK, with 225 million metric tons or 51% of Europe’s production. By 1937 Britain was still Europe’s main producing country with 42% of European output. In 1870 the production of oil was less than 1 million tons and in 1900 oil was still an insignificant source of energy; world production of 20 million tons met only 2.5% of world energy consumption. Because production was so limited there was little need for specialised vessels; tankers, mostly owned by Europeans, accounted for a tiny 1.5% of world merchant tonnage. But all this changed in the interwar period: by 1938 oil production had increased more than 15 times; it was 273 million tons and accounted for 26% of world energy consumption.3 The tanker fleet, had grown to 16% of world tonnage, and although it was mostly state-owned, independent tanker owners started to appear in the 1920s. The largest independent owners of the interwar period were the Norwegians.4

Technological innovations continued in the twentieth century; the choices and exploitation of technological advances by shipping entrepreneurs determined the path of world shipping. The first half of the twentieth century was characterised on the one hand by the use of diesel engines and the replacement of steam engines and on the other, by the massive standard shipbuilding projects during the two world wars. Diesel engines that appeared in 1890 were only used in a more massive scale on motor ships during the interwar period particularly in Germany and the Scandinavian countries; the cost of fuel being 30% to 50% lower than that of the steam engines. Standardisation of ship types and shipbuilding programmes were introduced in World War I when Germans sunk the allied fleets in an unprecedented submarine war. The world had not yet realised what industrialisation and massive production of weapons for destruction could do. The convoy system had been abandoned and naval battleships with their complex weapons were ready to confront the enemy. But it was the allied merchant steamships that were the artery of the war, transporting war supplies. And this armless merchant fleet became an easy target to the new menace of the seas: the German submarines. From 1914 to 1918, 5,861 ships or 50% of the allied fleet was sunk.

Replacement of the sunken fleet took place between 1918 to 1921 in US and British shipyards. It was the first time that standard types of cargo ships, the “standards” as they came to be called, were built on a large scale. The “standard” ships became the main type of cargo ship during the interwar period; they were steamships of 5,500 grt. It was these “standard” ships that Greeks, Japanese and Norwegian tramp operators purchased en masse from the British second hand market and expanded their fleets amongst the world economic crises. For similar reasons during World War II the United States and Canada launched the most massive shipbuilding programmes the world had known, using new and far quicker methods of building ships: welding. During four years they managed to build 3,000 ships, the well-known Liberty ships, that formed the standard dry-bulk cargo vessel for the next 25 years.5 Greek, Norwegian, British and Japanese tramp operators all came to own Liberty ships, in one way or another up to the late 1960s.

The second half of the twentieth century was characterised by an incredible increase of world trade that towards the end of the century was described as the globalisation of the world economy. The period of acceleration was up to 1970s; world trade from about 500 million metric tons in the 1940s climbed up to more than three billion metric tons in the mid-1970s. If the history of world maritime transport in the first half of the twentieth century was written by coal and tramp ships, in the second half the main players were oil and tankers. During this period, sea-trade was divided into two categories: liquid and dry cargo. Almost 60% of the exponential growth of world sea trade was due to the incredible growth of the carriage of liquid cargo at sea, oil and oil products. There was also impressive growth in the five main bulk cargoes: ore, bauxite, coal, phosphates and grain. To carry the enormous volumes required to feed the industries of the West and East Asia, the size of ships carrying liquid and dry cargoes had to be increased. The second half of the twentieth century was characterised by the gigantic sizes of ships and their specialisation according to the type of cargoes. The last third of the century was marked by the introduction of container ships. The new “ugly” ships revolutionised the transport system for industrial goods.

Up to the 1960s the main carriers of the world fleet remained the same with the US and Britain continuing to hold their decreasing shares in world shipping, followed by the continually rising Greece, Japan and Norway (Table 1). Flags of convenience were used informally by all maritime nations but in the immediate post-war years more extensively by Greek and American shipowners. Flags of convenience that were later to be called open registries became a key manifestation of the American maritime policy and a determining feature of post war shipping that guaranteed economical bulk shipping.6 By using flags of convenience, shipowners of traditional maritime countries were able to maintain control of their fleets benefiting from low cost labour. Sletmo relates the third wave of shipping with the transnationalisation of shipping through flagging out and dependence upon manpower from low-cost countries.7 After the repetitive freight rates crises of the 1980s flag of convenience were extensively used by all western and eastern maritime nations.

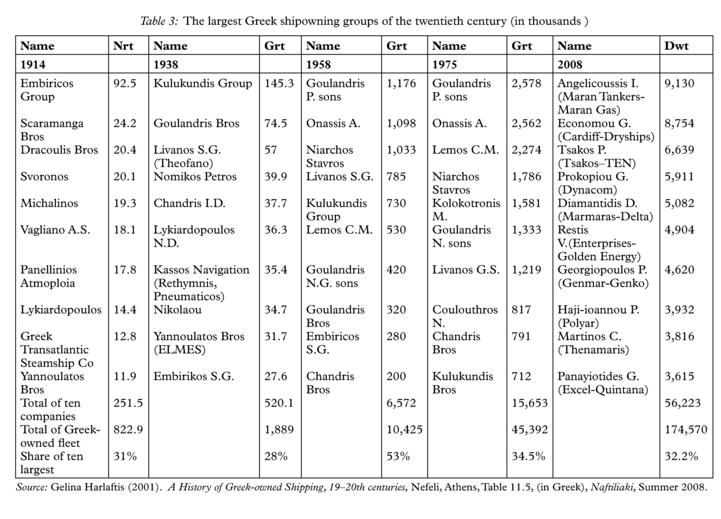

The 1970s marked a new era: this period was characterised by the final loss of the pre-dominance of European maritime nations, with the exception of the Greeks that continue to keep their first position to the present day, and of the Norwegians that despite the great slump of the 1980s, kept their share of the market in the 1990s. During the last third of the twentieth century the increase of the size of the world fleet shipping continued but slowed down. The United States has kept, mostly under flags of convenience, a much lower percentage, while Japan remains steadily in the second position (Table 1). The rise of new maritime nations from Asia was evident; by 1992 China owned more tonnage than Great Britain, while South Korea was close. The world division of labour in world shipping had changed dramatically.8 The booming markets of the period 2004–2008 contributed to the sharp increase in the world fleet, and to the slight change in the hierarchy of world maritime powers. Great Britain and Norway decreased their fleet and share in the world shipping, while Greece and Japan followed the opposite direction and increased both their tonnage and share. Germany made a very impressive comeback rapidly increasing its tonnage, especially of containerships. A remarkable change was that of China. Being the driving force of the world economy, China is continually developing its fleet. The conditions that prevail in the world shipping and shipbuilding markets after the collapse of the freight markets in 2008, make safe the forecast that sooner or later, China will become the driving force in world shipping.

3. Shipping Markets

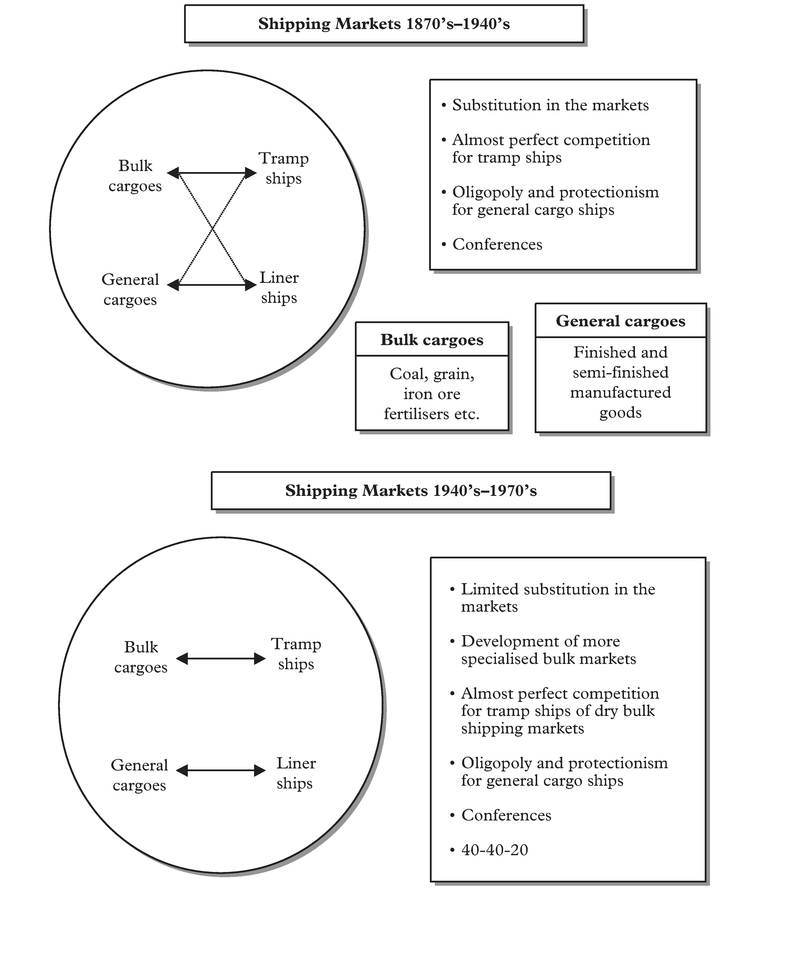

Following world shipping developments, the shipping markets had taken its twentieth century form since the last third of the nineteenth century. Before the 1870s the shipping market was unified. By the last third of the nineteenth century the distinction of the shipping market into two categories, liner and tramp shipping started gradually to adapt. Liner ships carried general cargoes (finished or semi-finished manufactured goods) and tramp shipping carried bulk cargoes (like coal, ore, grain, fertilisers, etc.) For the next 100 years, until the 1970s, liner and tramp shipping markets continued more or less on the same lines. This one century of shipping operations can be distinguished into two sub-periods (Figure 1).

During the first period, from the 1870s to the 1940s, the cargoes carried by liner and tramp shipping were not always clearly defined: liner ships could carry tramp cargoes and vice-versa. Although there was a substitution between the two distinct markets, the main structures of each one were diametrically different: oligopoly and protectionism for the liner market with the formation of the shipping cartels from the 1880s, the conferences, and almost perfect competition for tramp ships.

The unprecedented increase of world production and trade in the first post-World War II era brought more distinct changes in the structure of the markets that led to a gradual decrease of substitution between the markets.9 In tramp/bulk shipping, the introduction of new liquid bulk cargoes on a massive scale, like oil, and of the main dry bulk cargoes as mentioned above (coal, ore, fertilisers and grain) led to the creation of specialised bulk markets and to the building of ships to carry specific cargoes (Figure 1). The liner market continued along the same lines of oligopoly but witnessed increased competition into their protected markets from competitors from developing and socialist countries.

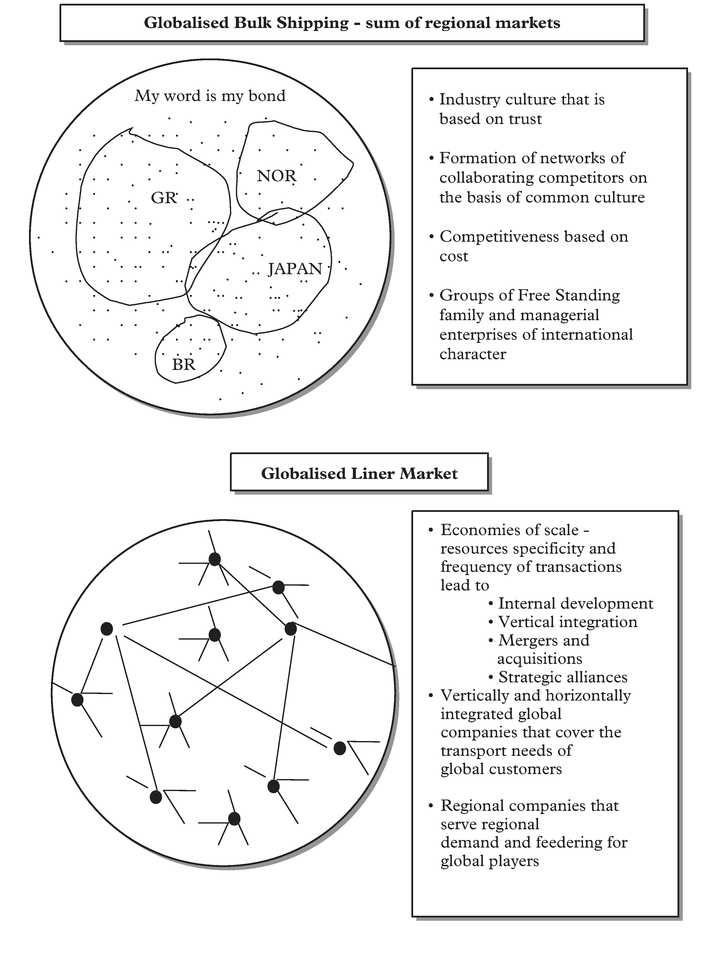

The 1970s were the landmark decade for the liner industry; unitisation of the cargoes, called also containerisation, had been introduced during the 1960s but became widespread during the 1970s, brought a revolution in the transport of liner cargoes (Figure 2).While in 1970 the world container fleet was of 500,000 TEU by 1980 this had increased by more than six times to reach 3,150,000 TEU.10 The new organisation of liner shipping that demanded excessive investments in infrastructure (terminals, cargo handling facilities, ships, equipment and agencies), led to an increase in ship and port productivity, an increase in ship size,11 and economies of scale and decrease of transport cost.12

Containerisation included radically new designs for vessels and cargo-handling facilities, global door-to-door traffic, early use of information technology, and structural change of the industry through the formation of consortia, alliances and international mega-margers.13 The above led to a total transformation of the liner shipping companies that became the archetype of a globalised multinational shipping company. The high capital investments required to operate a unitized general cargo transport system led to consolidation in liner shipping.14 This transformation was further provoked by the continuous trend to globalisation. Liner companies ought to serve the transport needs of their customer on a global basis. Although consolidation in liner shipping was increasing from the 1970s, during the 1990s it progressed faster. Liner companies were enforced to establish global networks in order to meet their customers’ needs. The enlargement of the companies’ size through mergers and acquisitions and the formation of global alliances were the necessary steps toward this. Strategic alliances between competitors have become the dominant form of cooperation in liner shipping.15 Alliances allow competing liner operators to exploit economies of scope and to offer to shippers global geographical coverage.16 It has been stated that increased complexity and intra-alliance competition among partners undermine the stability of strategic alliances.17 Indeed, many changes have been noted over the years. For example, the Grand Alliance in 1995 had as members the Hapag Lloyd, NYK, NOL, and P&O. A few years later MISC entered the alliance while NOL left to follow the New World Alliance. Recently MISC withdraw and today the alliance includes the Hapag-Lloyd, the NYK and the OOCL, the seventh, ninth and twelfth biggest liner companies.18

In parallel, strategies of internal development, merger and acquisitions have led to an increase in the concentration of the supply of liner services. The combined market share of the top four liner companies increased by 7% in a period of three years, i.e. from 31% in 2004 to 38.4% in 2007, while the Herfindahl—Hirschmann Index of the top four players (HHI–4) increased by 182%, from 268 in 2004 to 449 in 2007.19

For example, the biggest liner shipping company in the world, the Danish Maersk, which has a market share of 15%, operates more than 500 containerships ((two millions TEU) of which 211 are owned by the company) and more than 50 terminals worldwide, while its network includes more than 150 local offices worldwide. In 1999 Maersk acquired Sealand, the biggest American liner shipping company, the first company in the world to introduce innovative container technology, while in 2005 it acquired P&O Nedlloyd, then the third biggest liner company. It is thus evident that such a multinational company is a global network by itself and offers global services to its clients. This kind of development resulted in a total re-structuring in the port systems of the various regions and created the need for minor shipping lines to serve regional transport needs or offer feeder services for global liner companies. The major liner companies approach main international ports, from which minor shipping lines distribute the products to regional ports through the so-called feedering services.20 These two groups of companies, the big and minor container companies are not in competition with each other, rather they complement each other.

On the contrary, the development of tramp shipping did not involve such innovative technological developments and no dramatic changes took place in the organisation and structure of markets. The general pattern has not changed over the last 140 years. However, since the 1970s we are not talking of tramp shipping, but of bulk shipping since the type of ship does not characterise the market anymore, but instead the cargoes that are transported. Four main categories of bulk cargo are distinguished:21 the liquid bulk (crude oil, oil products and liquid chemicals), the five major bulk (iron ore, grain, coal, phosphates and bauxite), minor bulk (steel products, cement, sugar forest products etc) and specialist bulk cargoes with specific handling or storage requirements (motor vehicles, refrigerated cargo, special cargoes). Gradually need adapted to demand, and the “tramp” ship was replaced by specialised ships that were built according to the bulk cargoes and the specialised bulk shipping markets; reefer ships for the refrigerated cargo, chemical tankers for chemical gases, lpg and lng for liquefied petroleum and natural gas, heavy lift vessels for specific cargoes etc.

Globalised bulk shipping, even to the present day, is an industry based on trust. Companies form networks of collaborating competitors on the basis of common national cultures of traditional maritime nations such as Britain, Greece, Norway and Japan (Figure 2). Even members of the same network compete with each other and competitiveness is based on cost. During the twentieth century size did not play an important role in the competitiveness of the company.22 Bulk shipping consists of companies of various sizes – these vary from large companies of more than 50 large ships to single-ship companies that directly compete with each other. For example in 1970, the Greek-owned shipping company of Stavros Niarchos and the Norwegian shipping company of Wilhem Wilhelmsen which operated more than 60 ships co-existed and competed with the British Turnballs that operated five ships and the various Bergen-based and Piraeus-based small companies that operated ships of similar characteristics. Tramp shipping was mainly formed by groups of family enterprises which retained many characteristics of a multinational enterprise.23 No matter what the size of these enterprises, their organisation, structure and strategies had a lot in common.24

4. Shipping Companies

Overall analysis of the main trends in world shipping fleets and their markets throughout the twentieth century does not provide us with an understanding of the structure of the maritime industry. The core of the economy is the firm; the core of the maritime industry is the shipping company. In this section we will briefly review the actual players, the shipping companies of the four main twentieth century nations: the British, the Norwegians, the Greeks and the Japanese. In the first three European nations, we can distinguish similar patterns of organisation and structure in the shipping companies worldwide that concerned both liner and tramp shipping. First an important aspect of shipping companies was their connection with a specific home port; second was the ownership and management of the company by distinct families for multiple generations; third was the use of a regional network for drawing investment funds, and fourth was the existence of an international network of overseas agencies that collaborated closely with trading houses on a particular oceanic region, or on a particular commodity trade.25

4.1 The British

British commercial and shipping business in the nineteenth century developed along the lines of its colonial empire, and the inter-Empire and British external trade that was operated by close-knit global business networks. At the beginning of the twentieth century British shipping was world’s largest fleet owning 40% of the world’s tonnage, followed by Germany which owned one-fourth of its size. In 1918 a government committee reported that “at the outbreak of war, the British Mercantile Marine was the largest, the most up-to-date and the most efficient of all the merchant navies of the world”.26 The fleet was particularly hit during the interwar period, where it saw some of its leading shipping companies like the Royal Mail disintegrate and some of its main tramp-shipping owners leave the stage. It has been argued that British performance has been affected by the “unfair competition” of countries that subsidised their liner fleets like France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the United States, or the low-cost tramp operators like the Greeks that took large portions of its share in the Atlantic trade, and by the reluctance of British shipowners to invest in the new technology of diesel engines and tankers during the interwar period.27

World War II did not really affect the British share in world shipping which by 1948 had reached its pre-war level. Until 1967, Britain despite its decreasing share, remained world’s maritime leader and UK fleet continued to grow until 1975. Part of its 1975 tonnage, however, the year when the British fleet reached its peak, was foreign-owned and this “masked the extent to which British interest in merchant shipping had already declined before the downward plunge after 1975”.28 From 1975 to the beginning of the twenty-first century there was a continuous decrease in the UK register due to the “flagging-out” of the British-owned fleet. By 2007 British shipping under all flags was in tenth position with only 2.35% of world tonnage.29

The regional dimension in maritime Britain has played an important role in the organisation of both tramp and liner business. The main poles of liner shipping have traditionally been Liverpool and London followed by Glasgow and Hull. The newly emerging liner shipping companies from the mid-nineteenth century onwards were very strongly connected with a big home port, like London, Liverpool, Glasgow and Hull, where strong shipping elites were formed.30 For example, the Peninsular and Oriental (P&O), based in London, was established by Wilcox and Anderson in 1837 and specialised in trade with India and Australia; the Cunard Company, established by Samuel Cunard, Burns and the MacIvers in 1839 specialised in the north Atlantic; the British India (BI) shipping company, based in Glasgow, was established in 1856 by the MacKinnon shipping group and specialised in the Indian ocean; the Ocean Steam Ship Company known as the Blue Funnel Line, based in Liverpool, was established by the Holt family in 1865 and specialised in trade with southeastern Asia. The Union-Castle Line, was established in the 1850s and run by Donald Currie, specialised in South Africa by the 1870s, the Elder-Dempster based in Liverpool, was formed by Alexander Elder and John Dempster in 1868 and specialised in African trade; Lleyland, Moss, McIver and Papayanni, all based in Liverpool, were established in the 1840s and 1850s and were involved in the Mediterranean. Hull was the home port of the Wilson Line, established by the Wilson family – “Wilson’s are Hull and Hull is Wilson’s” –, that traded in all oceans and seas.31 In 1910 there were 65 liner companies that owned 45% of the British fleet. And all, during the previous 30 years, had organised themselves in closed cartels of the sea, the conferences, according to the oceanic region they traded, securing their share in the world market.32

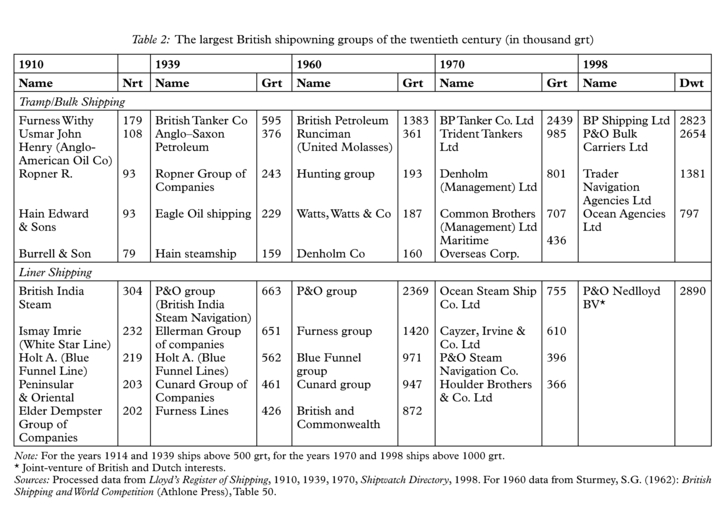

The five largest liner companies in 1910 were British India, White Star Line, Blue Funnel Line, P&O and Elder Dempster (see Table 2). Low freight rates and a widespread depression in the late 1910s led to intense competition and a wave of mergers that produced giant lines in the five years before World War I. The most notorious example is the Royal Mail Steam Packet Co that from 1903 to 1931 was led by Owen Philipps (later Lord Kylsant). Within 30 years Royal Mail reached its peak, owning 11% of British fleet, and its nadir in 1931 when it was liquidified, producing a major crisis

in British shipping business circles. In a remarkable series of acquisitions Royal Mail acquired Elder Dempster in 1910, Pacific Steam in 1910, Glen Line and Lamport Holt in 1911 and Union-Castle in 1912.33 Another giant emerged just before the war, when Peninsular and Oriental apart from the Blue Anchor Line, acquired British India Steam Navigation and its extensive shipping and trading interests in India. P&O continued its acquisitions and mergers throughout the interwar period and in contrast to Royal Mail, remained the largest British shipping concern throughout the twentieth century.

Mergers and amalgamations of lines into groups under common ownership continued in the interwar period and changed the structure of British liner shipping.34 The economic crisis of the 1930s hit British shipping hard. The contraction of the tramp shipping sector (which was lost to Norwegians and Greeks) and the concentration to fewer liner companies was evident: in 1939 there were 43 British liner companies which owned 61% of the fleet. The demolition of Royal Mail, and the intervention of the British banking system to save Britain’s largest liner concerns, brought a restructure of liner ownership in the 1930s that defined its path in the second half of the twentieth century.

As Table 2 indicates, in 1939 P&O, the Ellerman group of companies, Cunard, Blue Funnel and Furness Lines appeared in the top five positions. P&O through consecutive mergers and amalgamations became the indisputable queen of the Indian Ocean and Pacific routes; apart from British India Steam Navigation in 1914. In 1917 and 1919 it acquired another seven lines that serviced those routes. In the 1960s and 1970s P&O remained the largest shipping group of the world; after the 1970s it adjusted to the container revolution, adopted a globalised ownership, expanded to the port terminal business and diversified into the bulk, ferries and cruise sectors. In 1996 P&O Container Limited, the liner branch of the group, merged with Nedlloyd to form P&O Nedlloyd and the new company became the third biggest liner company, before its acquisition by Maersk Line. Ellerman acquired a number of smaller Liverpool lines that traded in the Mediterranean before World War I and its biggest acquisition was in 1916 when it amalgamated with Wilson Line; its importance contracted in the post-World War II period. Cunard, another giant of the “big five” of British shipping traditionally engaged in the Atlantic passenger services since 1840s, had acquired three or four lines during the second and third decade of the twentieth century. It profited largely from the demolition of Royal Mail when it acquired White Star Line in 1934. Persisting in passenger shipping, however, it eventually lost its importance in the post-war period.

The Blue Funnel (Ocean Steam Ship Company) group of companies owned by the Holt family exemplified family capitalism in liner shipping. Based in Liverpool and specialising in far eastern trade, it also profited from the demolition of Royal Mail and amalgamated with Elder Dempster which held the African trades. It continued to trade strongly well into the second half of the twentieth century. The Cayzer family from Glasgow formed the Clan Line in 1890, established the British and Commonwealth group in 1956 by amalgamating with the Union-Castle Line, another line that had belonged to the disintegrated Royal Mail group; it continued its business throughout the twentieth century. Until the beginning of the twentieth century the Furness group was one of the main British tramp shipping operators, who later diversified into liner shipping. By taking part in the acquisitions and amalgamations and exploiting the demolition of Royal Mail of which it acquired a fair share, it proved, along with P&O, to be one of the most important shipping groups of the twentieth century; it has also been among the first British liner groups to continue operating in tramp/bulk shipping.

Liner shipping companies are associated with the most glorious part of British shipping. Liner companies owned the most famous, luxurious steamships of the latest technology. British liner steamships carried millions of passengers, and became widely known as the proud manifestation of power of the mighty British Empire which ruled the waves. Most of the owners of British liner companies, among Britain’s most powerful capitalists, were commoners who became Lords or were knighted: Lord Kylsant of Royal Mail, Lord Inchcape of British India, Sir Alfred Jones of Elder Dempster, to mention only a few. British historians have told the stories of the main British liner business.35 But liner shipping throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries formed less than half of the large British fleet.

In fact, it was the less glorious ships of less technological achievement that formed more than half of the British fleet which fed the industries of the Empire. Tramp shipping formed the largest part of the British mercantile marine up to the Great War with 462 companies owning 55% of the fleet. The Industrial Revolution determined the areas in which British tramp operators developed in close connection with deep-sea export coal trade: The Northeast ports and Wales became the main hubs of British tramp-operators in combination with those of the Clyde in Scotland who were traditionally connected with the trading worldwide networks of the Scottish merchants.

In 1910 the shipping companies of the Northeast ports, namely Newcastle, Sunderland, Hartlepool, Middlesbrough, Whitby, Scarborough and Hull handled almost one third of British tramp shipping tonnage.36 Some of the most powerful British shipping families came from this area: the Furnesses, Turnballs, Ropners and Runcimans. The next most dynamic group in tramp shipping were Scottish tramp operators who handled 18% of British tramp shipping in 1910. Some of the best known Scottish tramp shipowning families were the Burrells and the Hoggarths. Wales also emerged as a generator of tramp companies. Wales drew human capital from the West Country as well and shipping companies established in Wales operated 9% of the British tramp fleet in 1910. With Cardiff as the central port, tramp shipping thrived in the Welsh ports from Chester to Llanelli.37 The best known Cardiff tramp operators were the Hains, Morells, Tatems and Corys. London and Liverpool drew branch offices from almost all these tramp operators and both cities handled 42% of the British tramp fleet in 1910.

Table 2 indicates the evident importance of tankers and the non-existence of independent tanker owners; one of the great failures of British tramp owners was that they did not enter the tanker business. The main big tanker owners remain the petroleum companies like the Anglo-American Oil Co in 1910, British Tanker Co and Anglo-Saxon Petroleum in 1939 and British Petroleum in the post-World War II period. The new structure in the organisation of tramp/bulk shipping, were the management companies under which one finds some of the traditional British tramp owners. Denholm Management is a good example of a management company. In 1970 it managed 38 ships for 17 shipping companies including Turnbull Scott Shipping.38

Contrary to the beliefs that want family capitalism to belong only to the Mediterranean, family prevailed in both the British liner and tramp maritime business.