LEGALLY BINDING THE COMPANY

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter you should understand:

How companies execute and become bound by deeds

How companies execute and become bound by deeds

When a company will be bound by an apparently properly executed deed or other formal document which in fact has been improperly executed

When a company will be bound by an apparently properly executed deed or other formal document which in fact has been improperly executed

The role and use of company seals

The role and use of company seals

The authority of the board of directors to bind the company

The authority of the board of directors to bind the company

The effect of s 40 of the Companies Act 2006

The effect of s 40 of the Companies Act 2006

The broad and narrow interpretations of the scope of s 40

The broad and narrow interpretations of the scope of s 40

How to ascertain whether an individual has authority to bind the company

How to ascertain whether an individual has authority to bind the company

When actual authority (express and implied) will be found to exist in the corporate context

When actual authority (express and implied) will be found to exist in the corporate context

When ostensible or apparent authority will be found to exist in the corporate context

When ostensible or apparent authority will be found to exist in the corporate context

The differences between implied actual authority and ostensible authority

The differences between implied actual authority and ostensible authority

The legal position of a company can be changed by deed or as a result of less formal documents and/or behaviour. The most frequently changed rights and liabilities are its contractual rights and liabilities and the main focus of this chapter is how a company acquires or becomes subject to contractual rights and liabilities (section 10.4). Contractual rights and liabilities can arise from contracts by way of deed but most arise as a result of simple contracts.

The key issue in relation to simple contracts covered in detail in this chapter, is whether or not an individual purporting to act on behalf of the company has authority to change the legal position of the company in the way in which he has purported to change it. The requirement of ‘authority’ of the individual is not, however, confined to simple contracts. Lovett v Carson Country Homes Ltd [2009] EWHC 1143 (Ch), considered at 10.2.3, is a reminder of the relevance of authority in relation to the execution of deeds and other documents.

This chapter begins with an examination of how a company becomes bound by a deed (section 10.2). Historically, seals were required to bind a company to a deed or to execute a document. Although this is no longer the case, seals are still in use today by some companies and it is appropriate to examine the relevance and role of company seals today (section 10.3), before turning to focus on contracts (section 10.4) and the authority of the board of directors and individuals (whether directors or not) to bind the company to a contract.

10.2 Deeds that bind the company

Deeds are used in a wider range of situations than entry into contracts. You will recall from your property and contract studies that deeds are formal documents, sometimes called instruments, affecting the legal rights and obligations of one or more legal persons. A deed may convey (i.e. effect the legal transfer of) property from one person to another. This type of deed is usually executed, or ‘made’, as a deed by the transferor (the person transferring the property) only. A deed may also contain the terms of an agreement entered into between two or more legal persons, in which case it is called a formal contract and is executed as a deed by all parties to the contract.

deed

A formal document conforming with the requirements of a deed set out in the Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989 and, in the case of a registered company, executed as a deed in accordance with the Companies Act 2006, s 44

10.2.2 Requirements for a company to be bound by a deed

A company can be a party to a deed. The requirements for a company to be bound by a deed, as a deed, are set out in a combination of the Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989 (c. 34) (referenced as the LP(MP)A 1989) and the Companies Act 2006. It is important to start with the LP(MP)A 1989, s 1(2) of which states:

SECTION

‘(2) An instrument shall not be a deed unless –

(a) it makes it clear on its face that it is intended to be a deed by the person making it or, as the case may be, by the parties to it (whether by describing itself as a deed or expressing itself to be executed or signed as a deed or otherwise); and

(b) it is validly executed as a deed by that person or, as the case may be, one or more of those parties.’

Section 1 of the LP(MP)A 1989 goes on to set out how an individual complies with s 1(2) (b), that is, how a natural person validly executes a document as a deed. The rules for how a company validly executes a deed to comply with s 1(2)(b) are found in ss 44 and 46 of the Companies Act 2006. Even if ss 44 and 46 are complied with, the document must also comply with LP(MP)A 1989, s 1(2)(a): it must be clear on its face that it is intended to be a deed.

Section 44 deals with execution of any document by a company and s 46 focuses on execution of a document as a deed. Section 44 provides that a document is executed by a company if either:

1. the company’s common seal is affixed to it; or

2. it is expressed to be executed by the company and is signed by:

two authorised signatories (two directors or one director and the company secretary); or

two authorised signatories (two directors or one director and the company secretary); or

a director in the presence of a witness who attests to his signature.

a director in the presence of a witness who attests to his signature.

Section 46 then adds that for a document to be validly executed as a deed for the purposes of LP(MP)A 1989, s 1(2)(b), the validly executed document must be ‘delivered as a deed’.

To deliver a deed is to evince an intention to be bound (Xenos v Wickham (1867) LR 2 HL 296). The act of executing a document indicates just such an intention unless the facts indicate otherwise. This is now captured in s 46(2) which states that a document is presumed to be delivered upon it being executed, unless a contrary intention is proved. Accordingly, although it is common in practice to state on the document the words ‘delivered as a deed’, these words are not strictly necessary. No reference to delivery needs to be made.

The presumption is that the deed is delivered upon it being executed. This is very often not the intention, the intention being for the deed to take effect on an agreed date that is not to be dictated by the availability of those required to execute it. It is common therefore to expressly address delivery on the face of the deed in order to pinpoint the date upon which the deed is to become effective. Typical language used in a contract by way of deed would be, ‘This deed is delivered on the date written at the start of this agreement.’

A deed which appears on its face to have been validly executed by a company may not have been validly executed. To protect third parties dealing with companies in good faith, the Companies Act 1989 introduced a provision that if a document purports to be signed in accordance with s 44(2) (see above), it is deemed to have been duly executed (s 44(5)). The subsection operates only in favour of a purchaser in good faith for valuable consideration. Consequently, a volunteer cannot use s 44(5) to argue that a document has been properly executed. Although the company also cannot rely on s 44(5), in a case in which a company seeks to rely on a defectively executed deed, ratification will often be possible.

The relationship of s 44(5) with the law on forged documents was considered by the Law Commission in its Consultation Paper entitled ‘The Execution of Deeds and Documents by or on behalf of Bodies Corporate’ (No 143, 1996) and its subsequent Report of the same title (No 253, 1998). Even though a majority of the consultees who commented were in favour of clarification, the Law Commission concluded, ‘We do not consider that there should be any legislative amendments to clarify the relationship between the presumptions of due execution and the rules governing forged documents.’ This recommendation has been described by the court in Lovett v Carson Country Homes Ltd [2009] EWHC 1143 (Ch) as, in hindsight, unfortunate.

In Lovett, the court considered the argument, based on Ruben v Great Fingall Consolidated [1906] AC 439 (HL), that a document with a forged signature is not even a ‘document’ and therefore a third party seeking to rely on a forged deed cannot rely on s 44(5) to validate it, for the simple reason that there is no document to validate. Justice Davis rejected the general proposition that a forgery can never be validated:

|

| ||||

The court in Lovett did not decide that any forged document that appears on its face to have been validly executed is capable of validation by s 44(5). Where there is no estoppel by subsequent acquiescence of the company (on which form of estoppel, see Morris v CW Martin & Sons Ltd [1966] 1 QB 716), and no ostensible authority (i.e. the person who presents the document to the third party has no ostensible authority either to warrant the genuineness of the document or to communicate the company’s representation of the genuineness of the document), it remains unclear whether, and if so, in which circumstances, s 44(5) may be successfully argued to validate a forgery.

common seal

A device used for making an impressed mark (the seal of the company) on a document to authenticate it

Company seals, or ‘common seals’, are anachronisms. They are literally metal presses that emboss the name and (in most cases) also the number of a registered company into the document to which they are affixed, usually where a red circle or ‘wafer’ has been stuck on to the document. No company is required to have a seal (s 45) and even if a company has a seal it is not necessary to use it unless the articles of the company require its use in particular circumstances. Deeds and other documents can be validly executed without a seal and share certificates can be issued without being sealed (to mention the prime examples of documents that have historically been sealed).

The Model Articles (Arts 49 (for private companies) and 81 (for public companies)) do not assume a company has a seal. They simply provide that any seal that a company has may only be used by authority of the directors. Once the seal has been affixed to a document, the Model Articles state that, unless the directors direct otherwise, a document must be signed by at least one authorised person in the presence of a witness who attests the signature. An authorised person for this purpose is a director, the company secretary or any person authorised by the directors for the purpose of signing documents to which the common seal is applied.

10.4 Contracts that bind the company

Reflecting back on your contract law studies you will recall that contracts can be classified into:

formal agreements (deeds); and

formal agreements (deeds); and

simple contracts (parol agreements).

simple contracts (parol agreements).

A company can be a party to either type of agreement. The difficulty a company has, like other artificial legal persons, is how it can enter into such contracts.

10.4.1 Formal agreements (deeds)

If the terms of a contract are set out in a document that makes it clear on its face that it is intended to be a deed and which is executed and delivered as a deed by the company in accordance with the rules set out earlier in this chapter, the company will be legally bound by that formal contract. The benefits of entering into a contract by way of deed are that, unlike in relation to simple contracts, it can be enforced without evidence of consideration and the limitation period for actions brought under it is 12 years, not six as it is for simple contracts (Limitation Act 1980, s 5).

Simple contracts range from oral agreements not committed to paper to detailed agreements between the parties captured in lengthy documents. Even if it is evidenced by a very formal-looking document, a contract remains a simple contract for legal purposes unless the document satisfies the rules regarding deeds.

The statutory provisions governing companies entering into simple contracts discussed in this chapter apply in addition to, and must be read subject to, any legal formalities required in the case of a similar contract made by an individual (s 43(2)). A contract for the sale of land, for example, must be in writing signed by or on behalf of each of the parties to the contract (Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989, s 2). Whether the parties are individuals, companies or a mixture of the two, an agreement for the sale of land will not be valid unless it complies with this formality. The Companies Act 2006 deals with the issues arising as a result of the company being an artificial rather than a natural person.

Contracts made by a company and contracts made on behalf of a company

A distinction is drawn in the Act between contracts that are made by a company by writing (s 43(1)(a)) and contracts that are made on behalf of the company by a person acting under the company’s authority, express or implied (s 43(1)(b)). To the extent that this section suggests that the contracts made by the company, as described in s 43(1)(a), do not involve the acts of individuals, who are thereby acting on behalf of the company in applying the seal or signing the document, it is misleading. Also, the omission of any reference to ostensible authority in s 43(1)(b) makes the section incomplete in terms of describing how a company may become bound by a contract.

Contracts made by a company

Sections 43(1)(a) and 44(4) together provide that a contract may be ‘made by a company’ by:

1. writing under its common seal; or

2. writing expressed to be executed by the company and signed by

two authorised persons, or

two authorised persons, or

a director in the presence of a witness who attests his signature.

a director in the presence of a witness who attests his signature.

Basically, if a contract is set out in writing and that document is either sealed or executed in accordance with s 44, the company will be bound by the contract. Contracts ‘made by a company’ for the purposes of s 43 may be deeds but if the document does not make it clear on its face that it is intended to be a deed, it can still be a contract ‘made by the company’.

Good reason to separate out subsection s 43(1)(a) from (b) would exist if s 43(1)(a) were to establish an absolute rule such that, provided the conditions for a contract being ‘made by the company’ appeared on the face of the document to have been complied with, there would be no room to argue an absence of authority on the part of the individual attaching the seal, the individual signing adjacent to the seal as required by the articles (of most companies) or the authorised signatories signing the document. It is not at all clear that the section achieves this level of clarity. As we have seen when we examined looking behind a deed, above, in the circumstances most likely to arise, s 44(5) applies to ban probing behind a purportedly executed document, whether or not it is a deed. Section 44(5) does not provide complete protection, however, and circumstances may exist in which it is permitted to look behind the face of a document, particularly if signatures have been forged.

Example

The seal of Company A Limited is affixed to a written contract between Company A Limited and B which is also signed by a director of Company A Limited whose signature is attested by a witness, as required by Company A Limited’s articles for use of the company seal. Is Company A Limited bound by the terms of the agreement?

The basic rule is that the agreement can be enforced against the company by a third party, B in this example (s 43(1)(a)).

Example

A written contract is expressed to be between Company A Limited and Company B Limited. At the end of the document it states, ‘Executed by Company A Limited:’. A director and the company secretary have signed the agreement in the space that follows. Is Company A Limited bound by the terms of the agreement?

The basic rule is that the agreement can be enforced against the company by a third party (ss 43(1)(a) and 44(4)).

In Redcard Ltd v Williams [2011] EWCA Civ 466 the Court of Appeal examined the meaning of the words ‘expressed, in whatever words, to be executed by the company’ in s 44(4) and rejected the argument that any particular words needed to be used to express the fact of execution by the company. Authorised signatories of Redcard Ltd had signed an agreement beneath the word ‘signed … seller’, with no words such as ‘by or on behalf of’ the seller appearing. As the word ‘seller’ was defined in the document and that definition included Redcard Ltd, Lord Justice Mummery concluded that ‘the signature at the end of the agreement under the words “signed … seller” could only mean that the document was expressed to be executed by Redcard’.

The authorised signatories for Redcard Ltd were also signing the contract of sale in order to bind themselves personally and Lord Justice Mummery agreed with the first instance judge that, ‘provided that, on a fair interpretation of the words in the contract, the reasonable reader would understand the signatures of the natural persons are signatures both on their own account and on behalf of the company, that is sufficient to amount to a proper execution for the purposes of s 44’.

Note, however, that a person who is a director and the secretary of a company cannot execute a document on his own, claiming to have signed as a director and the secretary, even if he adds his signature twice. This point is put beyond doubt by s 280.

Contracts made on behalf of companies

Companies can only perform acts through individuals and those individuals act on behalf of the company. Whether or not a contract has been made on behalf of a company usually involves consideration of agency law, as applied by the courts in the context of companies, and the Companies Act 2006.

The principal legal question arising in relation to whether or not a contract has been ‘made on behalf of a company’ is: did the individual or the organ of governance of the company (usually the board of directors) that purported to agree the terms on behalf of the company have legal power of authority to do so? A company will only be bound by a contract if, at the time the contract was allegedly entered into, the board of directors or the individual, on whose acts the third party is relying to allege that a contract has been entered into, was acting within the scope of its power or his authority as an agent of the company.

The individual, or agent, may be a director of the company but this is not necessary. A non-director employee may be an agent of the company and an independent contractor may be appointed by the company to act as its agent for one or more particular purposes. The starting point for analysis of the existence of authority to bind the company is the authority of the board of directors.

KEY FACTS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

10.5 Authority of the board of directors to bind the company

When we looked at the board of directors in Chapter 9 we saw that the articles of a company invariably state that the board is responsible for the management of the company and is empowered to exercise all the powers of the company for this purpose (Model Articles, Art 3). It is by the exercise of powers of the company that the legal rights and liabilities of the company are changed. If there are no other provisions in the articles relevant to the exercise of powers of the company, the board of directors has authority to bind the company to any contracts. Remember, the board of directors must act collectively in exercising the powers vested in it. The power to bind the company to a contract is exercised by the board of directors making a valid decision of the board, usually by board resolution (see Chapter 9 for how boards take valid decisions).

What if there are provisions in the articles, in addition to Art 3, relevant to the exercise of powers by the company? As noted in Chapter 9, notwithstanding the Art 3 default position in the Model Articles, it is not uncommon for the general authority of the board to exercise all powers of the company to be limited by articles that reserve certain powers to the shareholders. A typical example is an article requiring loans by the company for over a specified amount to be approved in advance by the shareholders.

What, then, are the consequences of the board of directors purporting to exercise a power of the company outside the board’s actual authority? For example, what are the consequences of the board purporting to commit the company to borrow a sum beyond the level the board is authorised by the articles to commit the company to borrow?

First, if they discover the board’s plans in advance, the shareholders may be able to obtain an injunction to prevent the board acting outside its powers. This common law right is expressly preserved by s 40(4).

First, if they discover the board’s plans in advance, the shareholders may be able to obtain an injunction to prevent the board acting outside its powers. This common law right is expressly preserved by s 40(4).

Second, each director who participates in the board decision to exercise the company power outside the powers of the board may be liable for breach of duty (see Chapter 11, directors’ duties, particularly s 171). Again, this potential liability is expressly preserved by s 40(5).

Second, each director who participates in the board decision to exercise the company power outside the powers of the board may be liable for breach of duty (see Chapter 11, directors’ duties, particularly s 171). Again, this potential liability is expressly preserved by s 40(5).

Finally, the loan contract may or may not be enforceable.

Finally, the loan contract may or may not be enforceable.

It is the enforceability of the loan contract that is examined here. Two sub-questions arise:

Can the third party enforce the contract against the company?

Can the third party enforce the contract against the company?

Can the company enforce the contract against the third party?

Can the company enforce the contract against the third party?

10.5.1 The Companies Act 2006, s 40 and board authority

The answer to whether or not a third party can enforce against a company a contract purportedly entered into by the board of directors when the board does not have the power to enter into the contract is now almost always determined by the application of s 40 of the Companies Act 2006.

SECTION

‘(1) In favour of a person dealing with a company in good faith, the power of the directors to bind the company, or authorise others to do so, is deemed to be free of any limitation under the company’s constitution.

(2) For this purpose –

(a) a person “deals with” a company if he is a party to any transaction or other act to which the company is a party.

(b) a person dealing with a company –

(i) is not bound to enquire as to any limitation on the powers of the directors to bind the company or authorise others to do so,

(ii) is presumed to have acted in good faith unless the contrary is proved, and

(iii) is not to be regarded as acting in bad faith by reason only of his knowing that an act is beyond the powers of the directors under the company’s constitution.’

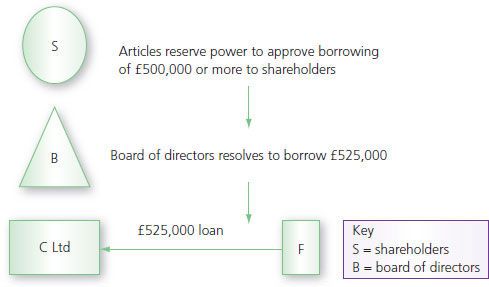

Consider the hypothetical scenario in Figure 10.1. Is C Ltd bound by the loan from F? Or, can F enforce the contract against C Ltd? To work out the answer, apply the following analysis:

Is the power to approve borrowings of £500,000 or more reserved to shareholders a ‘limitation under the constitution’ on the power of the board of directors for the purposes of s 40 (see s 40(1))?

Is the power to approve borrowings of £500,000 or more reserved to shareholders a ‘limitation under the constitution’ on the power of the board of directors for the purposes of s 40 (see s 40(1))?

Is F a ‘person’ entitled to rely on s 40 (see s 40(2)(a))?

Is F a ‘person’ entitled to rely on s 40 (see s 40(2)(a))?

Was F ‘dealing with [the] company’ (see s 40(2)(a))?

Was F ‘dealing with [the] company’ (see s 40(2)(a))?

Was F dealing ‘in good faith’ (see s 40(2)(b))?

Was F dealing ‘in good faith’ (see s 40(2)(b))?

Figure 10.1 Board of directors purporting to act outside its powers.

Person dealing with the company

In the words of the subsection, a person deals with a company for the purposes of s 40(2) (a) ‘if he is a party to any transaction or other act to which the company is a party’. As the subsection lays down a pre-condition to concluding that the person in question is a party to a transaction with the company, the language of the subsection is not at all helpful: it requires the existence of that which it is there to help to determine. Consequently, to avoid s 40 having no application at all, a purposive rather than a literal interpretation of s 40(2)(a) is required. Also, because the section is an implementation of the First European Company Law Directive, the Marleasing principle is once again relevant.

For the subsection to make any sense, in every case in which s 40 is relevant to a contract, ‘dealing with the company’ must mean being a party to a transaction to which the company merely purports to be a party (but to which, without s 40, it would not be a party). This calls for the courts to decide whether there are any circumstances in which a person, dealing with another who purports to be acting on behalf of the company, should not be entitled to argue that he has the protection afforded to third parties by Art 9(2) of the First Company Law Directive, as implemented (poorly) by s 40. Put another way, the subsection requires the courts to determine whether or not there are any circumstances in which the contracting process in issue was so defective that regardless of the good faith of the third party a court will not ignore the want of authority or other legal defect in the formation of the contract. In Smith v Henniker-Major & Co (A firm) [2002] 1 WLR 616 (CA), the leading case on the interpretation to be given to what is now s 40(2)(a), Carnwath LJ commented that a purposive approach to the section ‘suggests a low threshold’. On the underlying approach of the courts, however, he went on to comment:

JUDGMENT | ||

| I ‘[W]here, as here, the language of a statute, even one based on a Directive, has to be stretched in a purposive way to achieve its object, I see no reason why, in setting the limits, we should not be guided by what the common law would deem appropriate in a similar context.’ | |

The case is not particularly helpful in relation to the question when will a third party seeking to rely on s 40 not be able to because he is not dealing with the company. Rather, the facts raised the question whether or not a company insider is a ‘person’ for the purposes of the subsection.

CASE EXAMPLE | ||

| Smith v Henniker-Major & Co (A firm) [2002] 1 WLR 616 (CA) Smith, a director who was also the chairman and 30 per cent shareholder of a company held a meeting at which he alone was present and purported to pass a board resolution by which the company decided to assign to him the right to sue a firm of solicitors. The firm of solicitors argued that the assignment was invalid as the resolution was taken at a meeting without a quorum of two directors as required by the articles of the company. The director argued that he was a person dealing with the company in good faith and as such could rely on what is now s 40 to ignore the procedural shortcoming in the decision of the company which made the subsequent assignment unenforceable. At first instance the judge found that the director had been dealing with the company, could rely on the statutory provision, and therefore the assignment was valid. On appeal, Held: Smith could not rely on the section and the assignment was invalid. The words of the section were wide enough to include a director, but it was up to the courts to interpret the section and as there was no possible policy reason for interpreting it so as to enable a director in Smith’s position to ‘rely on his own mistake’, the court would look to the common law. The case of Morris v Kanssen [1946] AC 459 (HL) clearly applied, which decided that the law would not permit directors to rely on a presumption, ‘that that is rightly done which they have themselves wrongly done’ for to do so, ‘is to encourage ignorance and condone dereliction from duty’. | |

The case does not decide that a director will never be able to rely on s 40: indeed Carnwath LJ emphasised this and considered the facts in the case to be ‘quite exceptional’. It is possible for a director to seek to rely on s 40. The potential for s 40 to operate to bind the company to a contract with a director is confirmed by s 41. Section 41 provides that where, because of s 40, a company is bound by a contract with a director or a person connected to a director, the agreement will be voidable by the company (subject to protecting independent third party rights (s 41(6)), and the director and any other director who authorised the transaction will be liable to account to, or indemnify, the company (s 41(3)).

Dealing in good faith

As a reading of s 40(2)(b), set out above, indicates, a person dealing with the company is almost always going to be found to be acting in good faith for the purposes of s 40. The burden of proving that he was not in good faith is on the party asserting the lack of good faith, i.e. the company. In a sufficiently clear case, however, an absence of good faith may be found, and was so found in summary proceedings, without the benefit of a trial, in Wrexham Association Football Club Ltd (In Administration) v Crucialmove Ltd [2008] BCLC 508 (CA), a case principally about breach of directors’ duties. In summary proceedings in Ford v Polymer Vision Ltd [2009] EWHC 945 (Ch), Blackburne J dismissed any question of the third party being in bad faith in relation to the validity of a debenture but referred to trial the issue of the validity of an option so that the evidence relating to bad faith could be considered.

CASE EXAMPLE | ||

| Wrexham Association Football Club Ltd (In Administration) v Crucialmove Ltd [2008] BCLC 508 (CA) Two entrepreneurs, Mr Guterman and Mr Hamilton, who were interested in the exploitation of the assets of a football club established as a private company (Wrexham Association Football Club Ltd, ‘the Club’), misused the fiduciary position of Mr Guterman as a director and the chairman of the Club to benefit their property development interests. In an action by the Club seeking to avoid a deed, amongst other defences, it was argued by Mr Hamilton that a third party dealing with the Club/company could rely on the predecessor section to s 40 (s 35A) to assert the validity of a deed of declaration of trust executed by the Club/company. The deed had been executed by the Club/company by Mr Guterman and the company secretary. No disclosure of his personal interest in the transaction had been made to the Club/company by Mr Guterman and he and the company secretary had no authority to execute the declaration of trust. Mr Hamilton had made no enquiries as to whether the deed had been authorised by the Club/company and argued that he was under no requirement to do so, as the predecessor provisions to s 40(2) made clear. Held: The predecessor statutory provision to s 40 did not absolve a person dealing with the Club/company from any duty to inquire whether the persons acting for the Club/company has been authorised by the board to enter into the transaction when the circumstances were such as to put that person on inquiry. In the unusual circumstances of the case, Mr Hamilton had been put on inquiry. Accordingly, the corporate vehicle he used, Crucialmove, which was the beneficiary of the declaration of trust, could not satisfy the requirement of good faith. The deed of declaration of trust was not binding on the Club/company and s 40 (as it now is) could not help because of the absence of good faith. | |

In the course of delivering the judgment of the Court of Appeal, Sir Peter Gibson quoted at length findings of fact from the first instance judgment setting out the basis for Judge Norris QC’s finding of an absence of good faith.

JUDGMENT | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

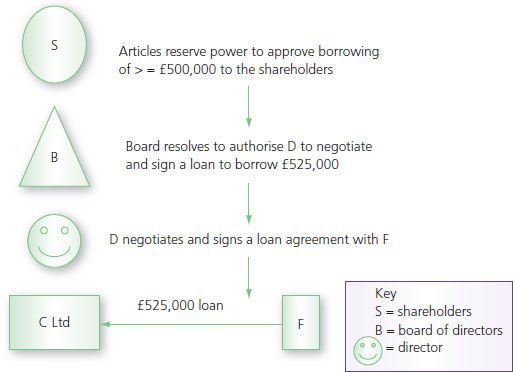

Consider the hypothetical scenario in Figure 10.2. Is C Ltd bound by the loan from F? The analysis to work out the answer is almost exactly the same as it was for the hypothetical scenario in Figure 10.1. The only difference in the legal analysis is that the language of s 40(1) relied on to override the limitation in the articles is the second power of the directors mentioned in that subsection, ‘the power of the directors to bind the company, or authorise others to do so’ (emphasis added). The power of the board of directors of C Ltd to authorise D to negotiate and sign a loan agreement with F is deemed to be free of the £500,000 loan limitation on the power of the board set out in the articles. D therefore has actual authority to bind the company to the loan with F.

Figure 10.2 Board of directors purporting to delegate a power it does not have.

A narrow or broad interpretation of the scope of s 40?

An important unresolved issue regarding the scope of application of s 40 arises out of the language in s 40(1) which deems the power of the directors to bind the company or authorise others to do so, free of any limitation under the constitution. Section 40(1) does not state that the power of any individual is deemed free of any limitation under the constitution (the authority of an individual is discussed at section 10.6 and you may understand the following discussion better after you have read that section).

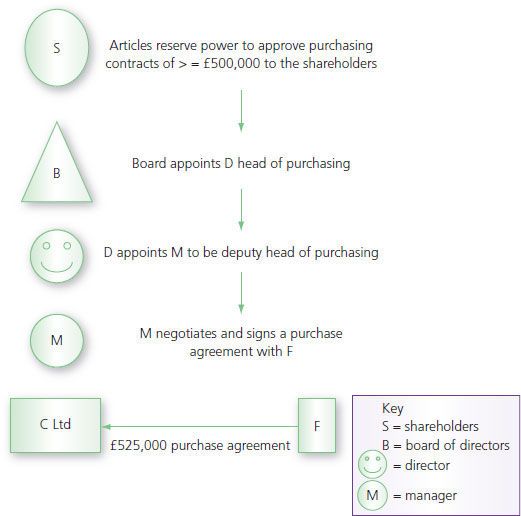

Consider a third party dealing with an individual they believe to have authority to bind the company and who would have authority, based on agency principles, but for a limitation in the company’s constitution. The individual did not receive his authority directly from the directors. Does s 40 prevent the company from arguing that the individual has no power/authority because of the limitation under the constitution? A purposive interpretation of the section would suggest s 40 should be construed broadly and the company should not be able to rely on such an argument, i.e. that s 40 should protect the third party in such a circumstance. The explanation would be that s 40 not only overrides the limit on the powers of the directors, and any limit on another who has been authorised directly by the directors, but also overrides the limit in relation to the authority of every person whose grant of authority (down the chain of management in the company) can be traced back to the board of directors, the benefit of s 40 overriding operating at every level of grant of authority even where there is no express grant of authority by the board, indeed, even where the authority of the individual is ostensible authority. A narrow interpretation of s 40, on the other hand, would limit s 40 overriding of any limit in the constitution strictly to circumstances in which the directors exercised the power to enter into contracts or the directors directly (and possibly also expressly) authorised another person, and, consequently, the company could rely on the limitation in relation to anybody further down the chain of command.

This moot issue is illustrated diagramatically in Figure 10.3. C Ltd in Figure 10.3 would be bound by the purchase agreement with F if a broad interpretation of s 40 were adopted but would not be bound if a narrow interpretation were adopted.

Figure 10.3 Manager is appointed to an office which carries the usual authority to enter into a contract entry into which, in the articles of the company in question, is reserved to the shareholders.

Situations outside s 40

Section 40 will not be relevant in a number of situations including the following:

If the company is seeking to rely on a contract and the third party is arguing an absence of authority, s 40 cannot be used by the company because it only operates in favour of the contractor (but note the potential for the company to ratify the contract).

If the company is seeking to rely on a contract and the third party is arguing an absence of authority, s 40 cannot be used by the company because it only operates in favour of the contractor (but note the potential for the company to ratify the contract).

If there is no validly appointed board of directors, s 40 will not be relevant.

If there is no validly appointed board of directors, s 40 will not be relevant.

If the third party is dealing with the shareholders, s 40 will not be relevant.

If the third party is dealing with the shareholders, s 40 will not be relevant.

If the third party is not acting in good faith, and the company can establish this, s 40 will not assist him.

If the third party is not acting in good faith, and the company can establish this, s 40 will not assist him.

Potentially, if the individual purporting to act as agent of the company has not been directly granted express authority by the directors (a moot issue).

Potentially, if the individual purporting to act as agent of the company has not been directly granted express authority by the directors (a moot issue).

In all these situations (though only potentially in the last mentioned circumstance) the enforceability of the contract will be determined by the common law.

10.5.2 The common law position and board authority

Where s 40 does not apply, the starting point at common law is that if the board enters into a contract on behalf of the company without authority to do so, the contract cannot be enforced by the third party contractor against the company. Nor may the company enforce the contract against the third party contractor (Re Quintex Ltd (No 2) (1990) 2 ACSR 479). The inability of the company to enforce the contract can usually be overcome quite easily by the company adopting or ratifying the contract.

Ratification will be brought about in most cases by the shareholders passing an ordinary resolution (Grant v UK Switchback Railways Co (1888) 40 Ch D 135 (CA)), although it is possible for a company to ratify a contract by conduct. Ratification validates the acts of the board (or any other purported agent previously lacking authority) from the point in time when the acts took place and is, therefore, ‘equivalent to an antecedent authority’ (Koenigsblatt v Sweet [1923] 2 Ch 314). Remember from our consideration of pre-incorporation contracts that the company must have been in existence at the time the agent purported to act on its behalf. It is not possible to ratify an act performed when the principal (the company) did not exist (see Chapter 4).

Where a restriction on the power of the board exists, the board has no actual authority to bind the company (the principal), but what of ostensible authority? Historically, arguments that the board had ostensible authority were met and defeated by the constructive notice rule which deemed a person dealing with a company to have notice of the contents of the company’s public documents. The most important public documents of a company are its memorandum and articles of association (although, as we saw in Chapter 5, the memorandum is much less important today than it used to be). Consequently, a third party would be deemed to have constructive notice of any limitation on the power of the board contained in the articles. For a third party to argue he had relied on a representation that the board had authority would contradict this constructive knowledge, fail and the contract would be unenforceable for lack of authority.

The harshness of the constructive notice rule on third parties is mitigated by the rule in Royal British Bank v Turquand (1856) 6 E&B 327. Turquand’s Case established what is sometimes referred to as the ‘indoor management rule’, namely that a third party may assume that internal procedures specified in a company’s public documents as having to be gone through to provide the board with authority have been gone through, even though they may not have been gone through. Note, however, that a third party who has been put on notice that those procedures have not been gone through (by something more than constructive or actual notice of the public documents) may not rely on the internal management rule. Wrexham Association Football Club Ltd (in Admin) v Crucialmove Ltd [2007] BCC 139 (CA) (considered at section 10.5.1) is an example of circumstances in which a third party will be considered to have been put on notice that internal procedures have not been complied with and denied the right to rely on the rule in Turquand’s Case.

A third party who can rely on Turquand’s Case to mitigate the constructive notice rule may argue that the board has authority based on a statement in the articles that the board has authority to enter into the type of contract in question, the limitation on the power (such as its exercise in relation to contracts above a certain value being subject to shareholders’ approval by resolution) simply calling for an internal procedure that he can assume has been gone through. Be sure to distinguish this situation from a situation in which the board is not authorised to enter into the type of contract in issue, for example, where the articles contain an absolute prohibition on directors entering into a certain type of contract, in which case no basis on which to argue the existence of ostensible authority will exist. This will be the case where a contract is outside the objects of the company. As was the case in Turquand’s Case itself, the ostensible authority argument applies where the third party finds ‘not a prohibition … but a permission to do so on certain conditions’ (per Jervis CJ).

10.6 Authority of individuals to bind the company

The articles of a company typically empower the board of directors to delegate any of its powers (Model Articles, Art 5), and authorise further delegation of its powers by any person to whom it has delegated powers. A board of directors typically delegates powers not by expressly using the terms ‘delegation’ and ‘powers’ but by allocating management responsibilities to individuals and approving the appointment of individuals to named roles within the company. In the absence of limitations on the powers of the board, if the allocated management responsibilities or the performance of the role involves the individual acting so as to legally bind the company, the individual will be an agent of the company with actual authority to bind the company.

If, and to what extent, the board’s allocation or appointment of an individual actually delegates powers to that individual is a matter of construction of the terms of the allocation or appointment in the factual context in which it takes place. The authority of the agent is a question of fact. Exactly the same analysis applies to further delegations of power by those to whom the board has delegated powers. And so the powers of the company cascade down, to be exercised at different levels within the company, yet the authority of every agent of a company can be traced back to the board of directors.

The authority described in the previous paragraphs is actual authority. Concern to protect third parties dealing with companies resulted in the development of the concept of ostensible authority and the authority of an agent nowadays may be either actual authority (express or implied) or ostensible authority. Ostensible authority is also called apparent authority: the terms are interchangeable. Although based on very different legal reasoning, both actual and ostensible authority can be traced back to the board of directors and, ultimately, to the articles of the company. The company is, in agency terminology, the principal.

Actual authority is based on a consensual agreement between the principal (the company) and the agent. The principal consents to the agent exercising the legal power of the company to enter into contracts. The basis of actual authority was described by Diplock LJ in Freeman & Lockyer v Buckhurst Park Properties (Mangal) Ltd [1964] 2 QB 480.

JUDGMENT | ||

| ‘An “actual” authority is a legal relationship between principal and agent created by a consensual agreement to which they alone are parties. Its scope is to be ascertained by applying ordinary principles of construction of contracts, including any proper implications from the express words used, the usages of the trade, or the course of business between the parties. To this agreement the contractor is a stranger.’ | |

JUDGMENT | ||

| ‘If the question arises between the principal and the agent – either of them claiming against the other – actual authority must be proved. There is no question of ostensible authority as between those two parties.’ | |

Actual authority may be express actual authority or implied actual authority.

Example 1: Express actual authority

The board of directors of Company A Limited passed a board resolution authorising the finance director, on behalf of the company, to negotiate and enter into a ten-year lease of a pasteurising machine from Extra plc, Full plc or Glow plc. The finance director has express authority to bind the company to a lease falling within the description in the board resolution. He may contract with any of Extra plc, Full plc or Glow plc.

Example 2: Express actual authority

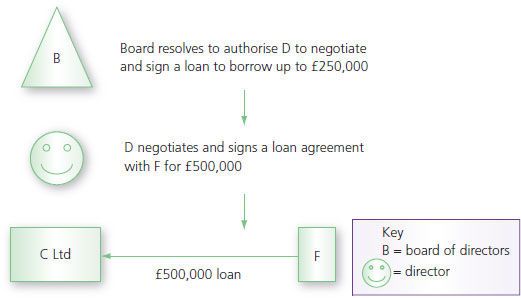

Consider the hypothetical scenario in Figure 10.4. Is C Ltd bound by the loan agreement with F?

Turning now to focus on implied actual authority, the leading case on implied actual authority in the context of a company as the principal is Hely-Hutchinson v Brayhead Ltd [1968] 1 QB 549 (CA). It confirms that a person appointed by the board to a position within a company will have usual authority, that is, implied actual authority, to do all such things as fall within the usual scope of that office. The case actually demonstrates another point, that is, the importance of taking into account the conduct of the company and the individual and all the circumstances of the case.

Figure 10.4 Individual director acts outside the express actual authority granted to him by the board of directors.

| Hely-Hutchinson v Brayhead Ltd [1968] 1 QB 549 (CA) Richards was chairman of the board of an industrial holding company (Brayhead) and its chief executive or ‘de facto managing director’. Richards regularly entered into contracts on behalf of Brayhead which he disclosed to the board afterwards, sometimes seeking formal ratification after he had committed the company. The board acquiesced in Richards’ entry into contracts. Brayhead was planning to merge with another company, Perdio. In these circumstances, Richards signed contracts purportedly binding Brayhead to guarantee Perdio’s borrowings from a third party and indemnifying the third party against certain losses. The question arose, did Richards have authority to bind Brayhead to such contracts? At first instance, Roskill J found that Richards had ostensible authority. On appeal, the Court of Appeal Held: Richards had actual implied authority. Lord Denning MR found that Mr Richards had no express authority to enter into the contracts in issue on behalf of the company, nor was such authority implied from the nature of his office. Although Richards had been duly appointed chairman of the company, in itself, that office did not carry with it authority to enter into the contracts in issue without the sanction of the board. ‘But I think he had authority implied from the conduct of the parties and the circumstances of the case … such authority being implied from the circumstance that the board by their conduct over many months had acquiesced in his acting as their chief executive and committing Brayhead Ltd to contracts without the necessity of sanction from the board’ (emphasis added). | |

Example 3: Implied actual authority

The board of directors of Company B Ltd resolved to approve the appointment of Paul Bailey to the position of head of marketing with responsibility for running the marketing department. Past heads of marketing have signed a range of contracts on behalf of the company such as contracts for the purchase of marketing services including television advertising time and billboard space. Paul Bailey has implied actual authority to enter into agreements on behalf of Company B Ltd but the exact scope of his implied actual authority to enter into contracts is not clear. The scope of authority is ascertained from the conduct of the board and the circumstances of the case of which the appointment to the role is an important part but it is not the only fact relevant to the existence and scope of Paul Bailey’s authority.

In Smith v Butler [2012] EWCA Civ 314, Arden LJ examined the law relevant to ascertaining the implied authority of a managing director in the course of concluding that on the facts the MD in question had no implied authority to suspend the executive chairman.

JUDGMENT | ||

| ‘28 | … [the] proposition … that, in principle, the implied powers of a managing director are those that would ordinarily be exercisable by a managing director in his position [i]n my judgment … is correct. In Hely-Hutchinson v Brayhead [1968] 1 QB 549 at 583, Lord Denning MR held that the board of directors, on appointing a managing director, “thereby impliedly authorise him to do all such things as fall within the usual scope of that office.” Mr Dougherty’s proposition is also supported by the passage that Mr Berragan cited from Gore-Browne on Companies. Another way of putting that point is that the managing director’s powers extend to carrying out those functions on which he did not need to obtain the specific directions of the board. This is simply the default position. It is, therefore, subject to the company’s articles and anything that the parties have expressly agreed. In essence, the issue is one of interpreting the contract of appointment or employment in the light of all the relevant background, and asking what that contract would reasonably be understood to have meant (Attorney General of Belize v Belize Telecom Ltd [2009] 1 WLR 1485, PC, and see my judgment in Stena Line v Merchant Navy Ratings Pension Fund Trustees Ltd [2010] EWCA Civ 543 at 36–41). |

29 | On this basis, as might be expected, the test of what is within the implied actual authority of a managing director coincides with the test of what is within the ostensible authority of a managing director: see Freeman & Lockyer v Buckhurst Park Properties (Mangal) Ltd [1964] 2 QB 176. | |

30 | The holder of the office of managing director might today more usually be called a chief executive officer in (at least) a public company. He or she has generally to work on the basis that his appointment does not supplant that of the role of the board and that he will have to refer back to the board for authority on matters on which the board has not clearly laid out the company’s strategy. He or she would thus be expected to work within the strategy the board had actually set. | |

Now consider Example 3 with slightly amended facts. Consider that the resolution appointing Paul Bailey expressly stated that the head of marketing had authority to commit the company to marketing contracts to a value of no more than £500,000 and Paul Bailey signs a contract purporting to commit the company to purchase £600,000 of marketing services. An agent who is subject to an express limit on his authority cannot have implied actual authority that exceeds that limit. It is in just such a case that a third party must turn to ostensible authority.

ostensible authority

The authority that one can assume a person purporting to be an agent has based on a representation made by a person authorised by the company. Also known as apparent authority